Media | Articles

How an eclectic restoration shop became the Miller authority overnight

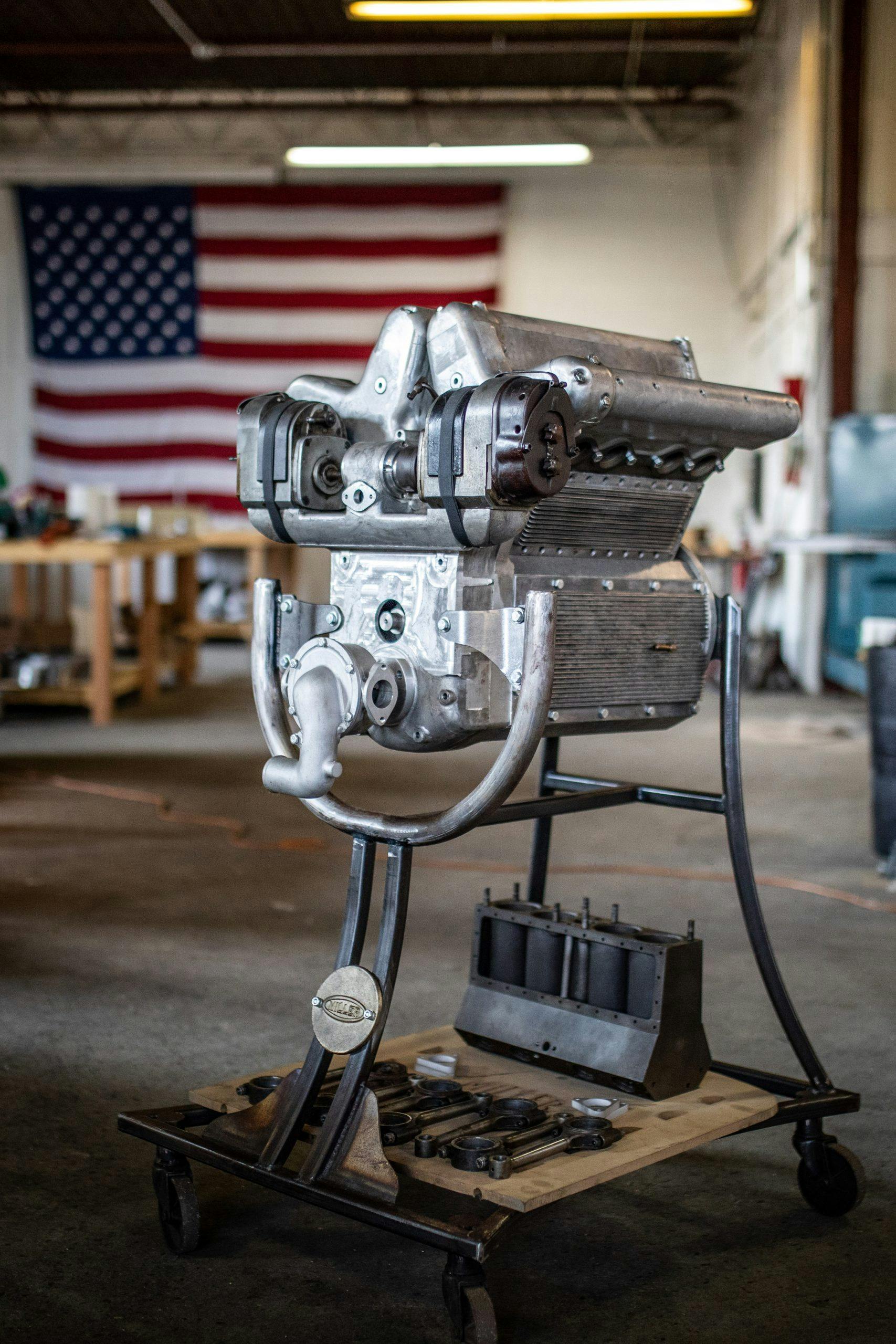

Last year, on a damp spring morning, fabricator Ed Linn and several of his employees stuffed a 26-foot U-Haul, two pickup truck beds, and two enclosed trailers with parts, patterns, and drawings made by American race car builder Harry A. Miller. From 1926 to 1934, Miller-designed cars won nine Indianapolis 500s. Miller-based Offenhauser engines won an additional 29, starting in 1935.

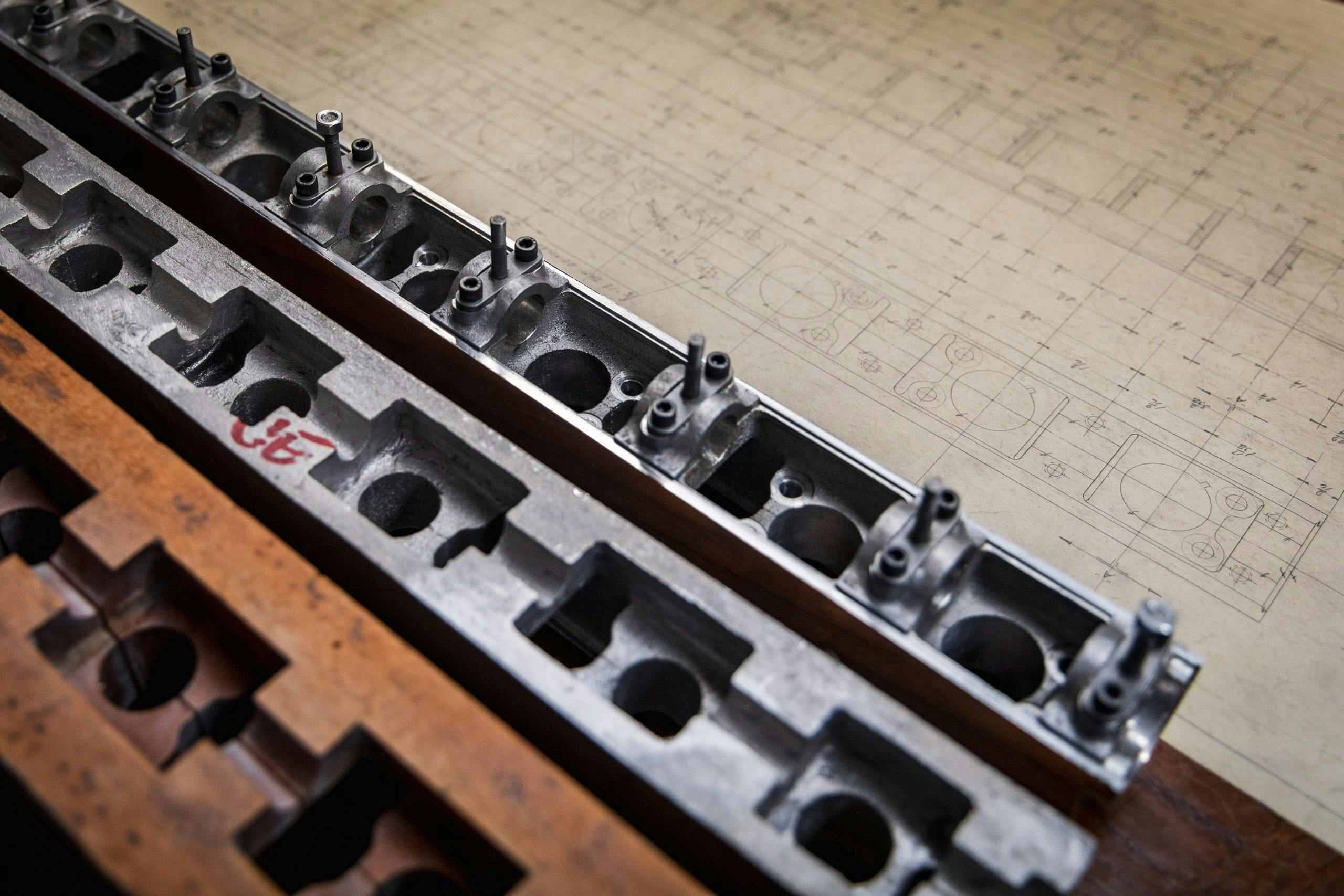

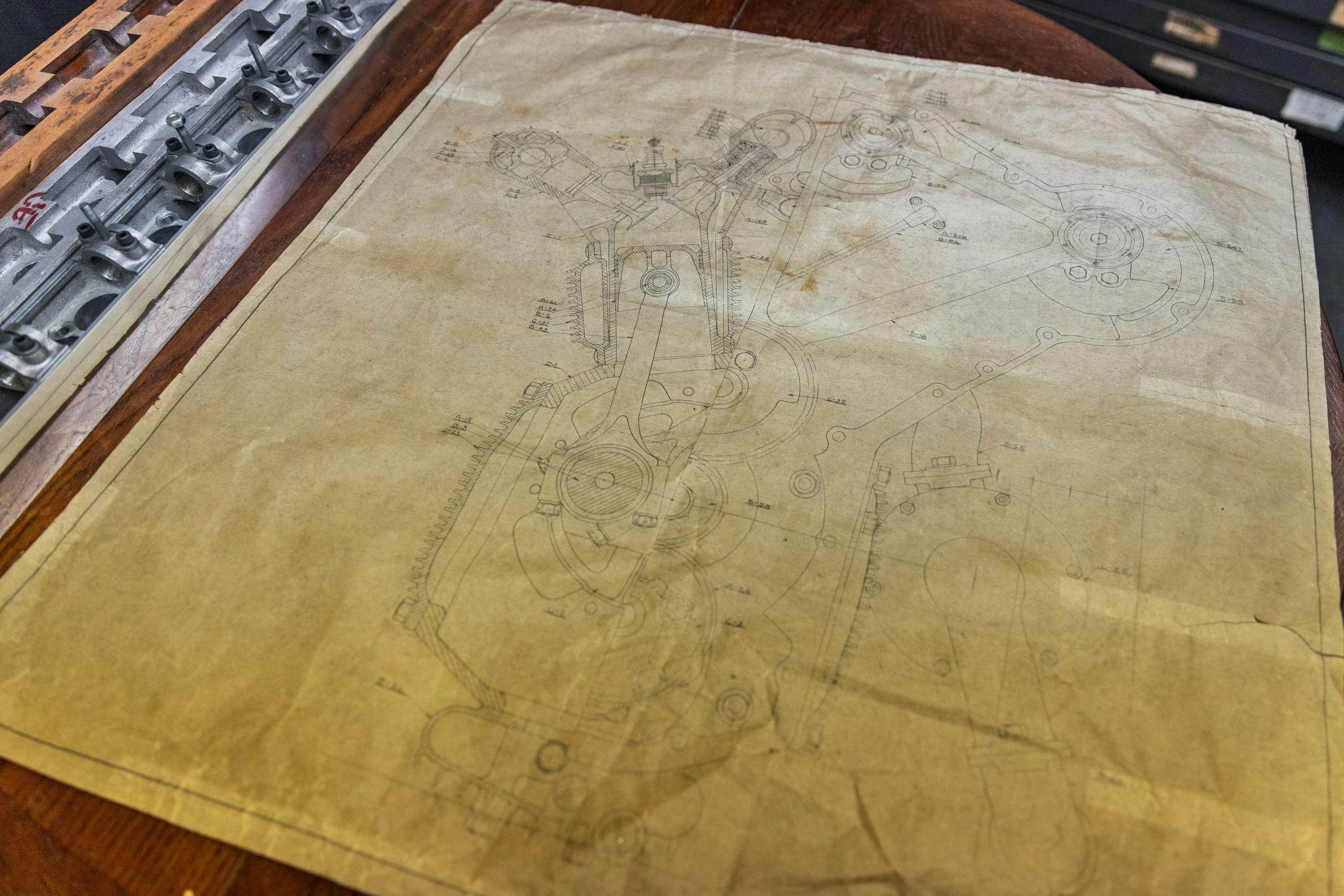

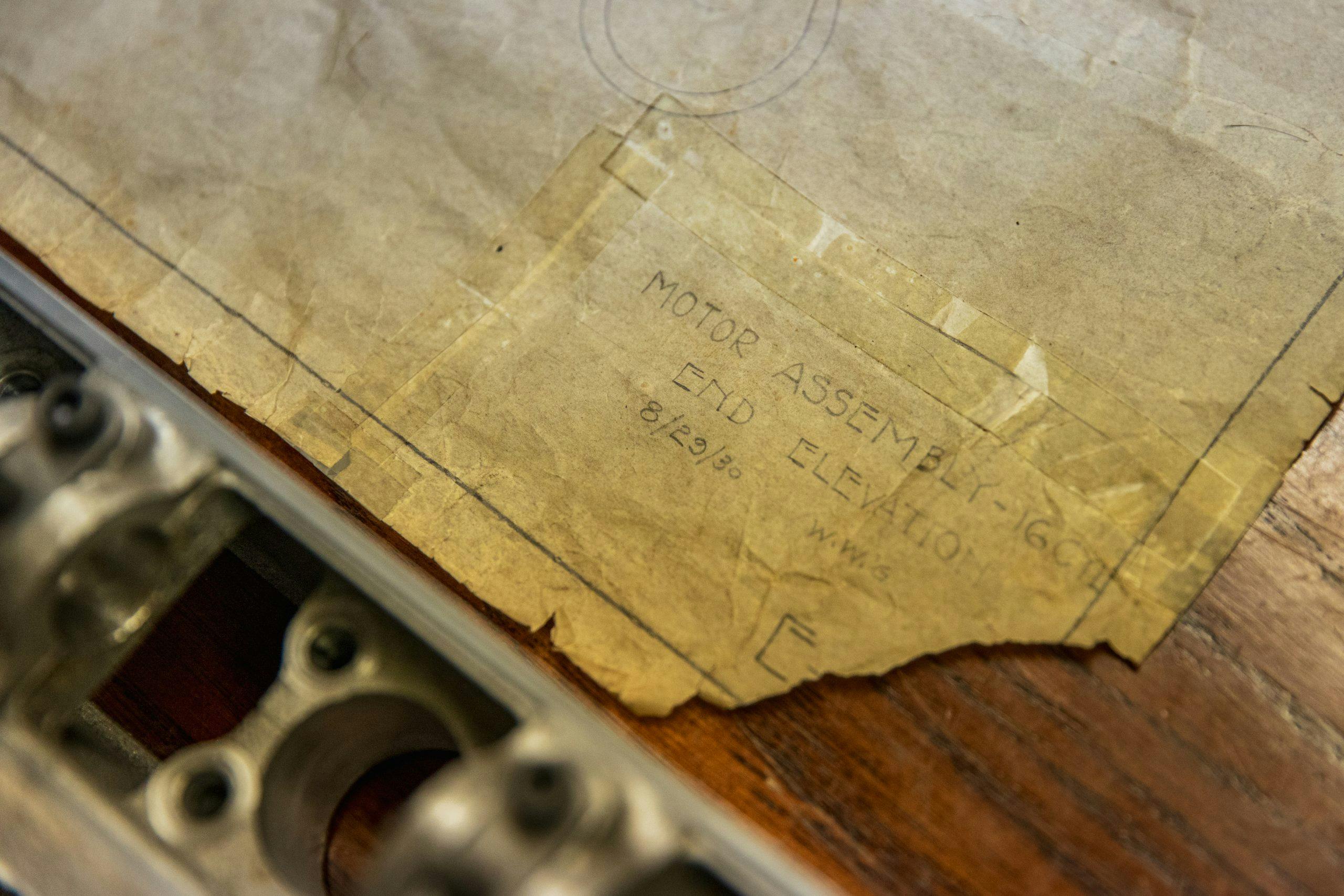

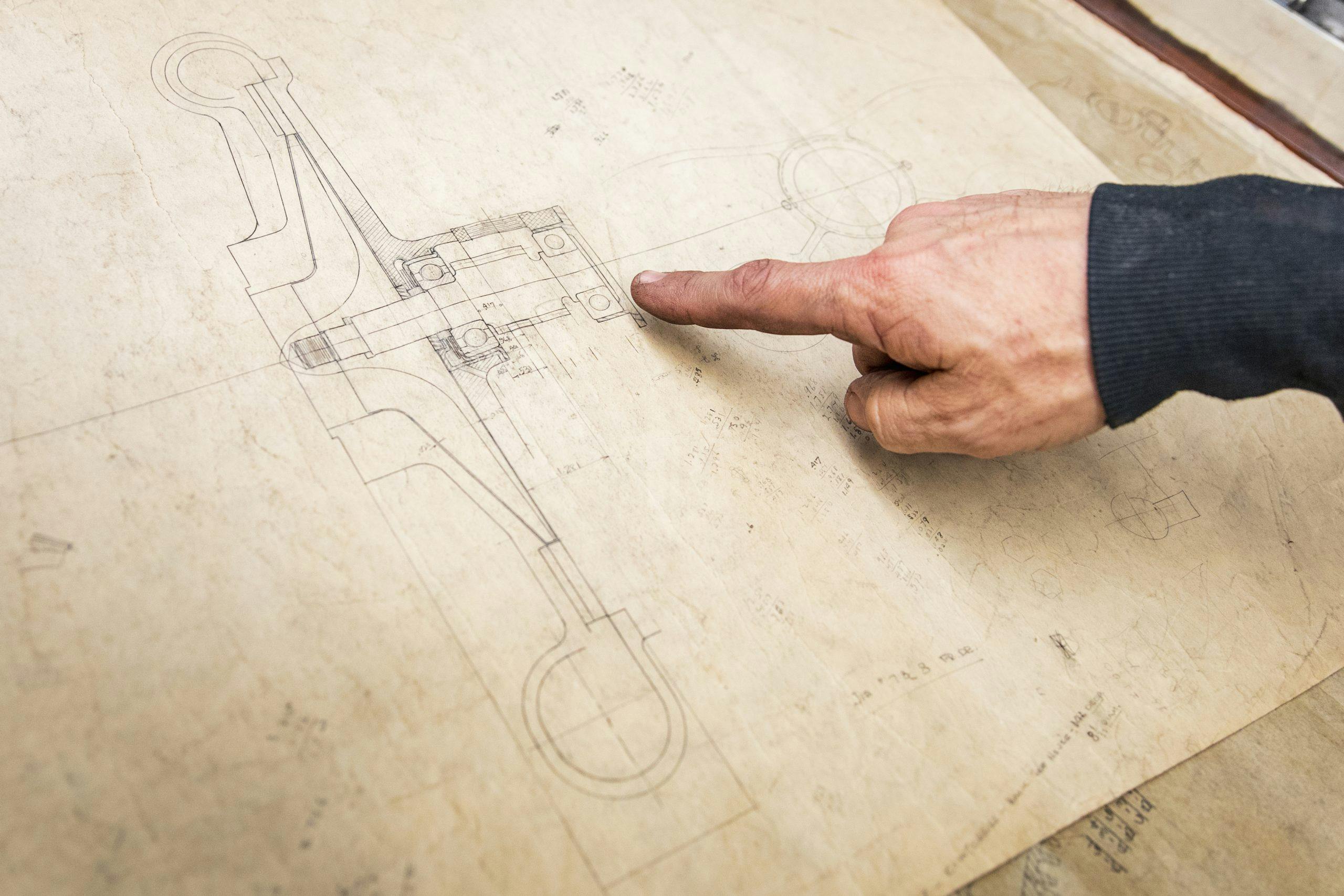

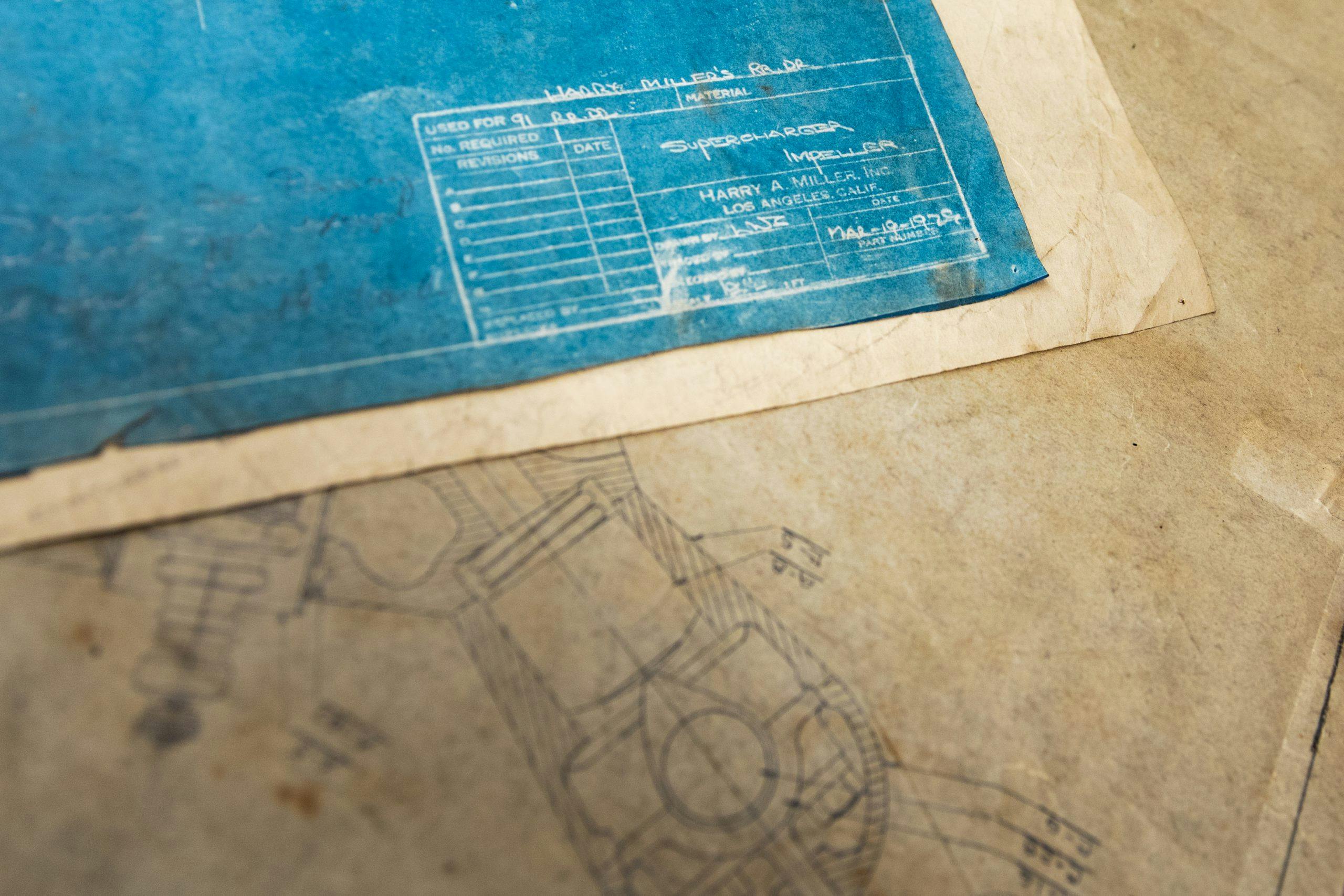

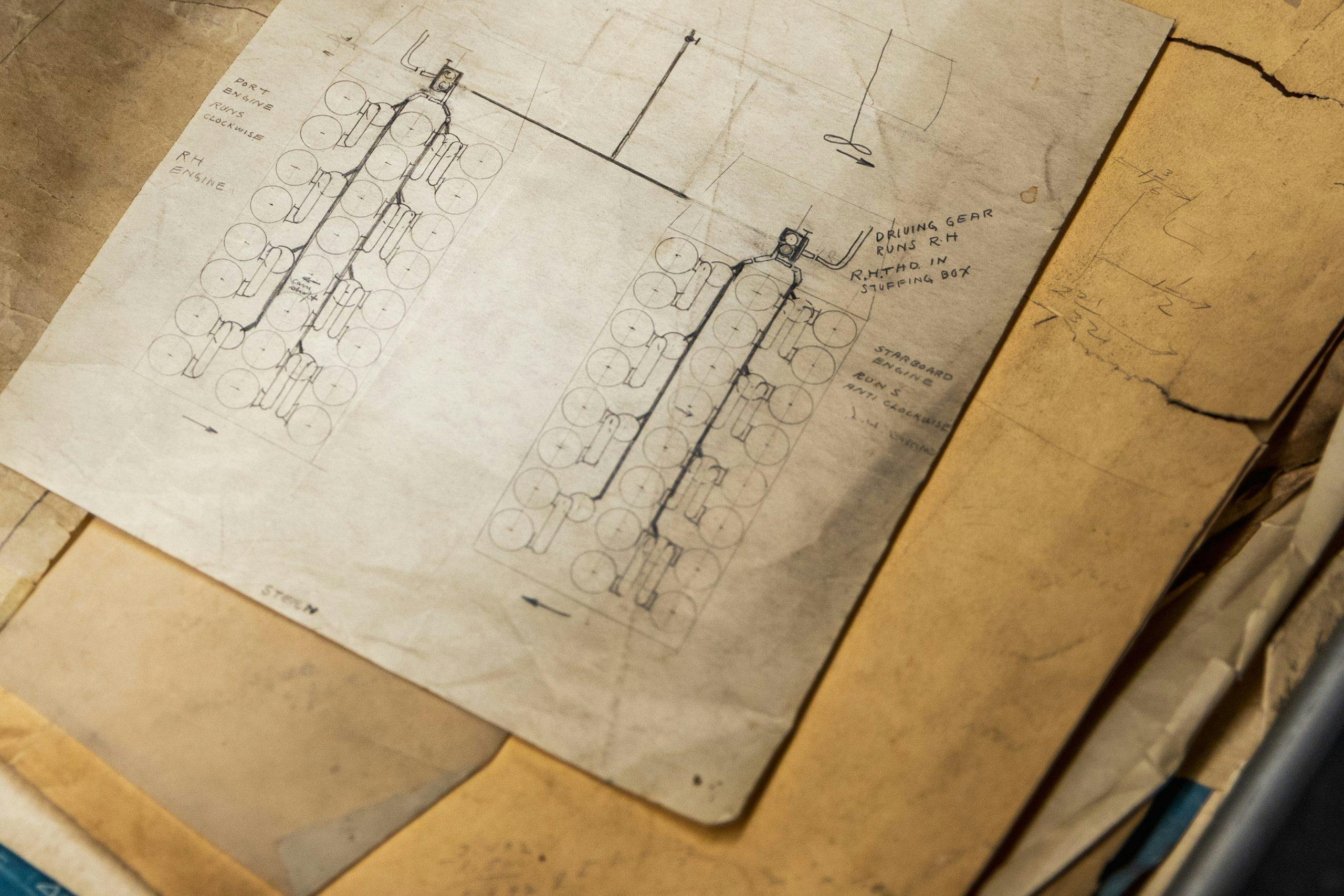

Now, Linn and his crew were loading blueprints covered in Miller’s shorthand math, wooden bucks emblazoned with his signature, and engine components thought only to exist on monochrome film. At nearly a century old, the Smithsonian-grade collection is the majority of all known Miller inventory. Linn, a longtime Miller fanatic, got wind the previous owner was looking to sell the lot. Once he and the seller agreed to terms, the collection traded hands in less than 24 hours. Now more than a thousand patterns, 10,000 technical drawings, and countless Miller projects fill the walls and the halls of Linn’s shop, EDL Services, in Troy, Michigan.

The shop is housed inside a pair of gray concrete buildings tucked away at the end of an alley and yoked by a small parking lot. Aside from a few rusty carcasses outside, there’s nothing that hints at the wealth of history and provenance inside Linn’s buildings.

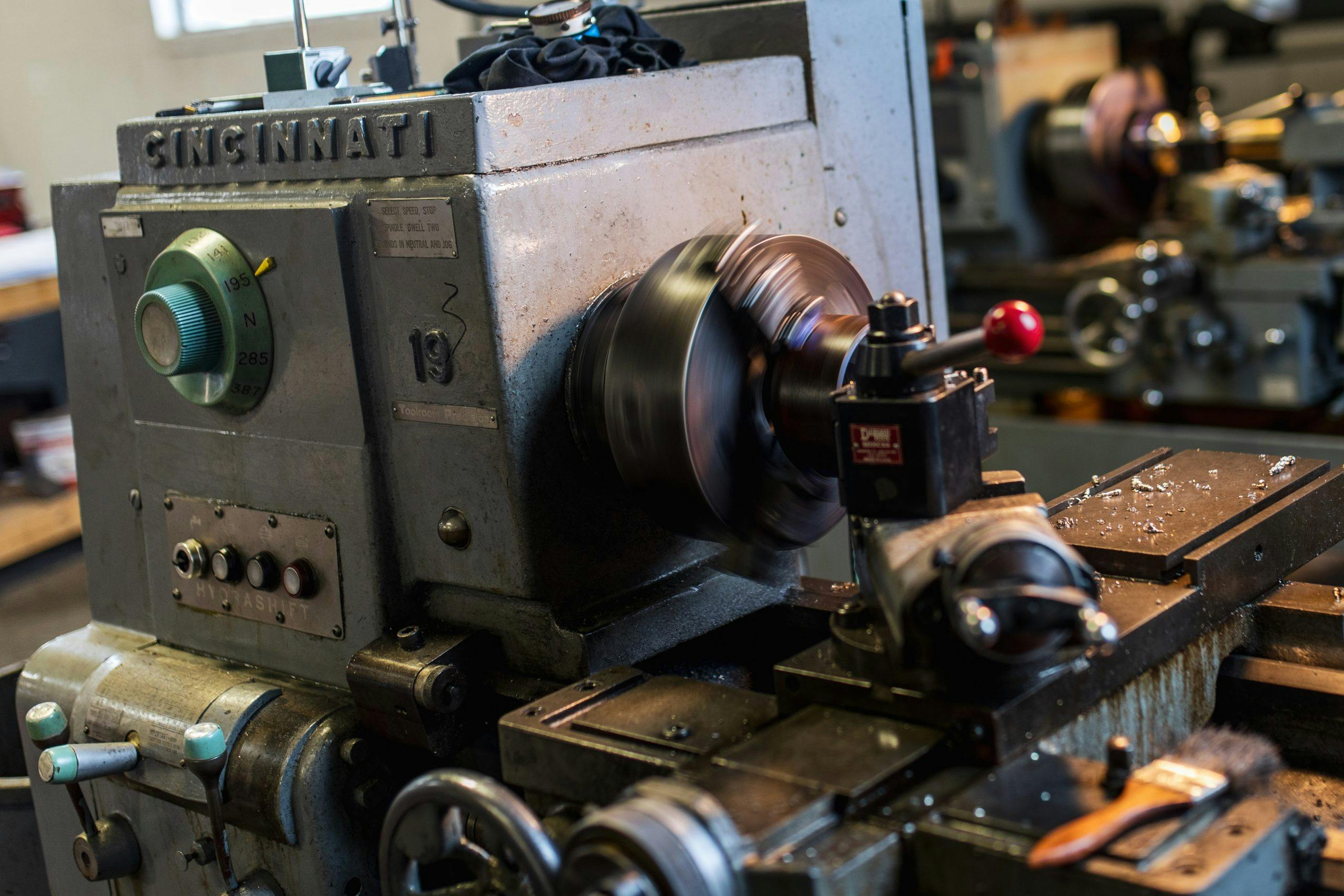

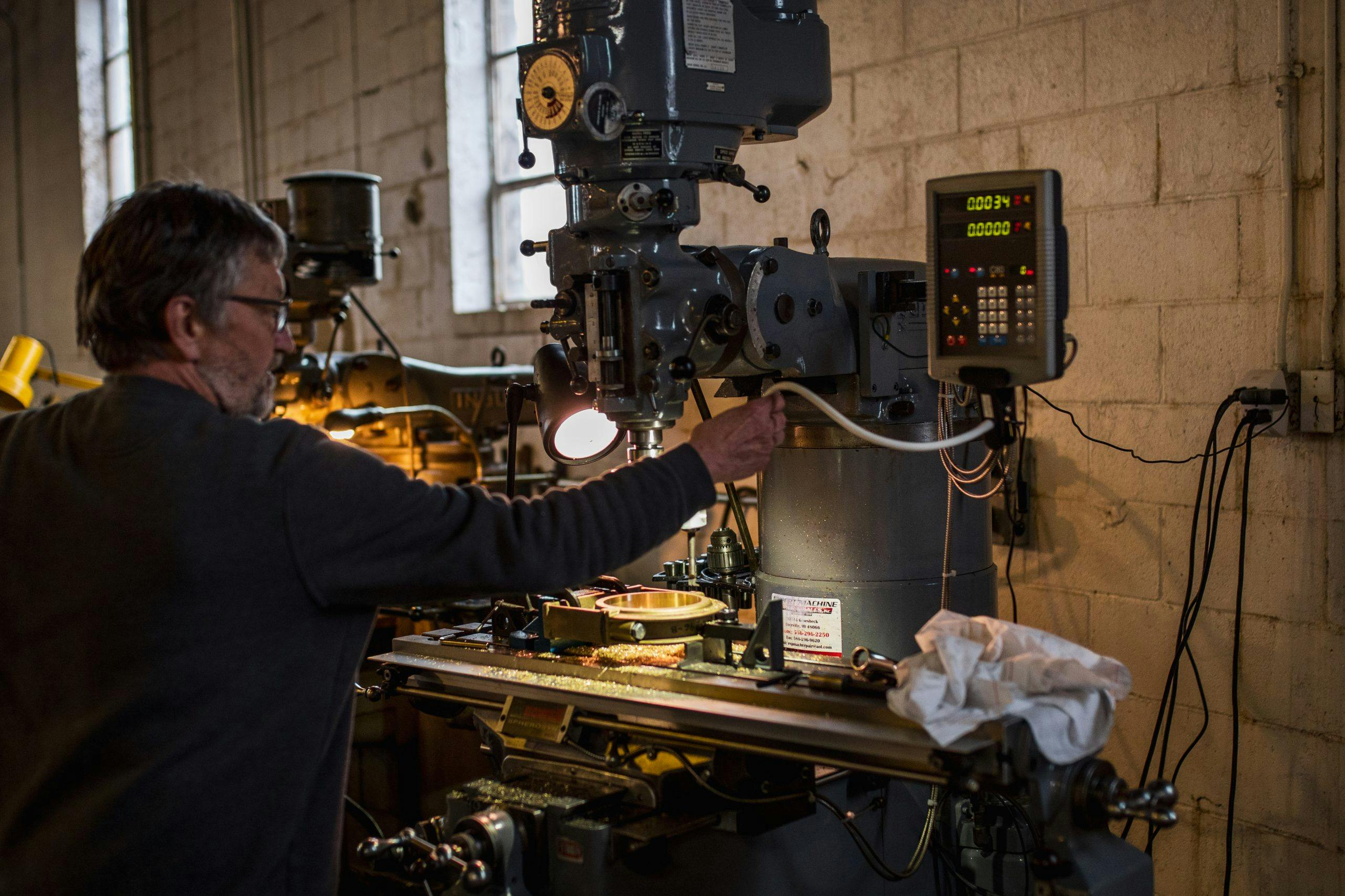

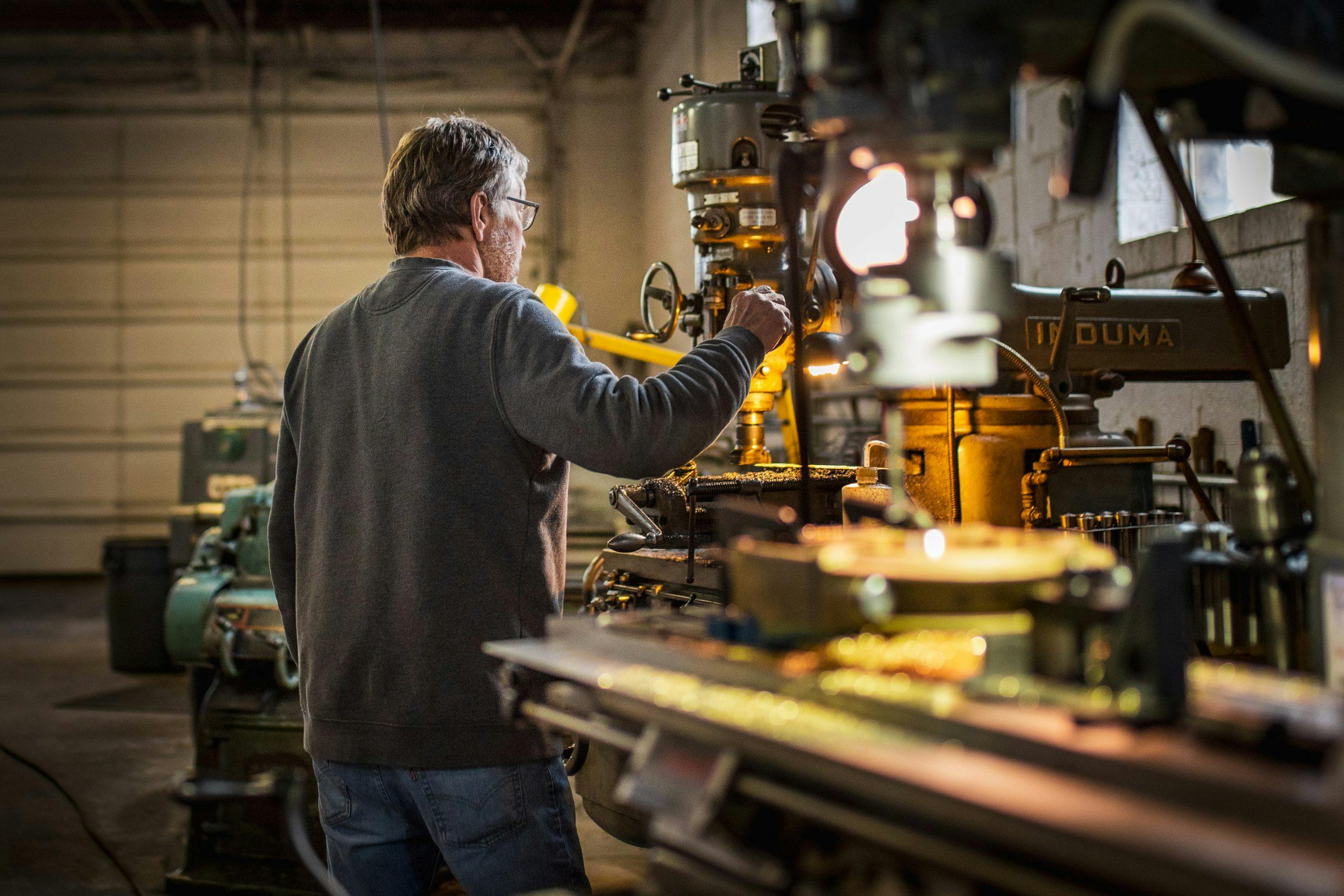

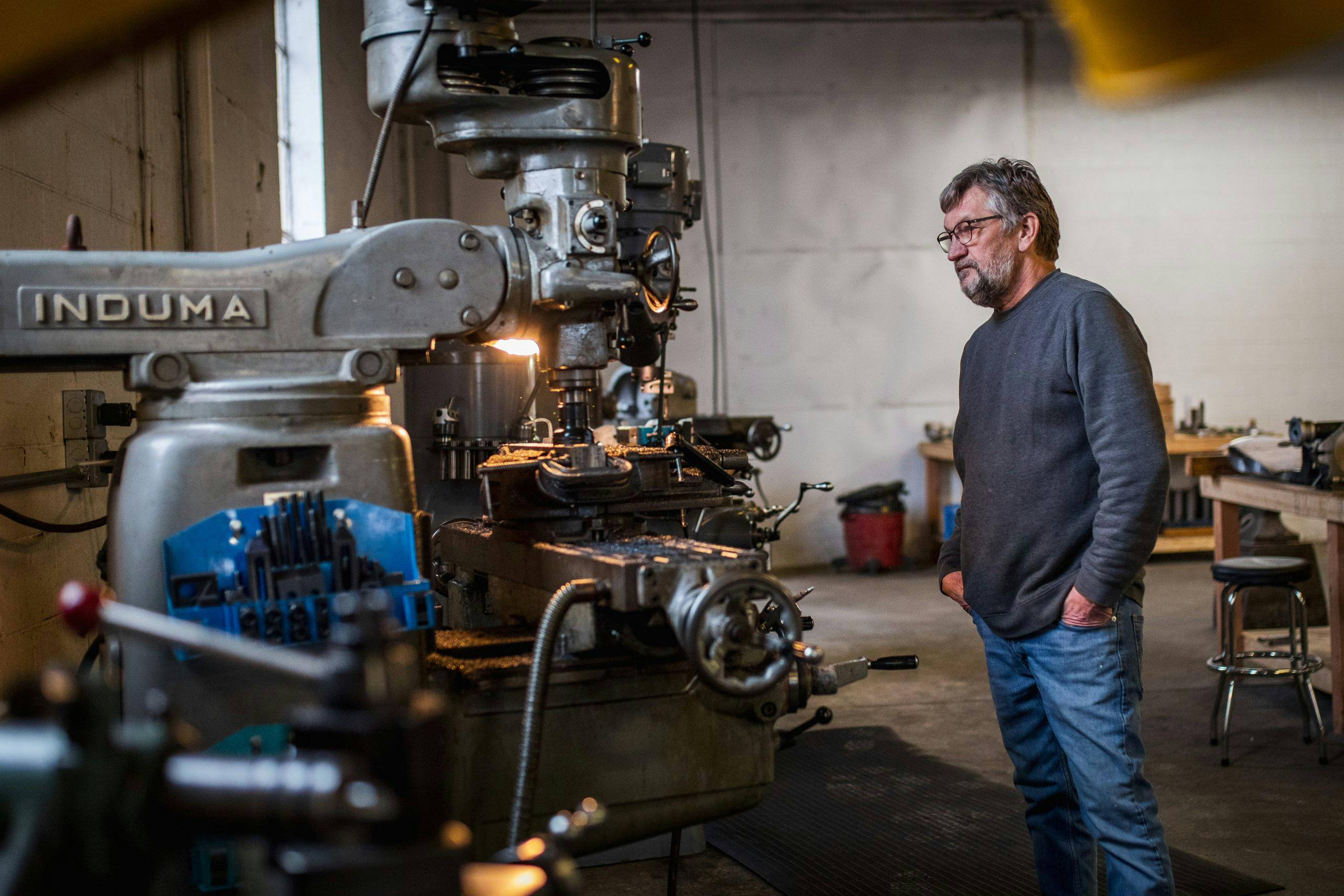

Behind the chipped metal door of the east building, prehistoric-looking machines hum. A 7000-pound Lodge & Shipley lathe showers the concrete floor with a metallic confetti of steel, chrome, brass, and sparks. Coachbuilt cars sit beneath dusty covers and line the near wall. Linn’s nine full-time employees diligently design, fabricate, assemble, paint, and polish at workstations scattered around the place. Seems everyone at EDL can do everything. Business partner Josh Shaw is also a draftsman, a fabricator, and a painter, having pinstriped two of EDL’s recent projects. “We don’t really have titles,” says Shaw. “Everyone just gets stuff done.”

And what the folks at EDL Services get done are roughly 20 to 30 projects at a time. “We’ll work on anything for anybody,” says Linn. Though the Miller collection has taken center stage over the past year, the crew recently finished a frame-off restoration on a 1976 Datsun 280Z while simultaneously refreshing a 1913 Oakland. “I’ve lucked out and been able to make a career out of it.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Now in his 50s, Linn still has the frame of a man who could have played lineman for the Detroit Lions. A drum brake’s backing plate looks like a coaster in his massive mitts. But his imposing stature is at odds with his quiet demeanor and an encyclopedic knowledge of all things automotive—a proficiency gained by decades of experience. “My shop teacher in high school got me into old cars, and as a sophomore, I started working at a local shop in Troy,” Linn says. He then spent 22 years at one of Troy’s premier restoration facilities, Classic and Exotic Service, a shop that specialized in rebuilding Duesenbergs. He left in 2003 to start his own business.

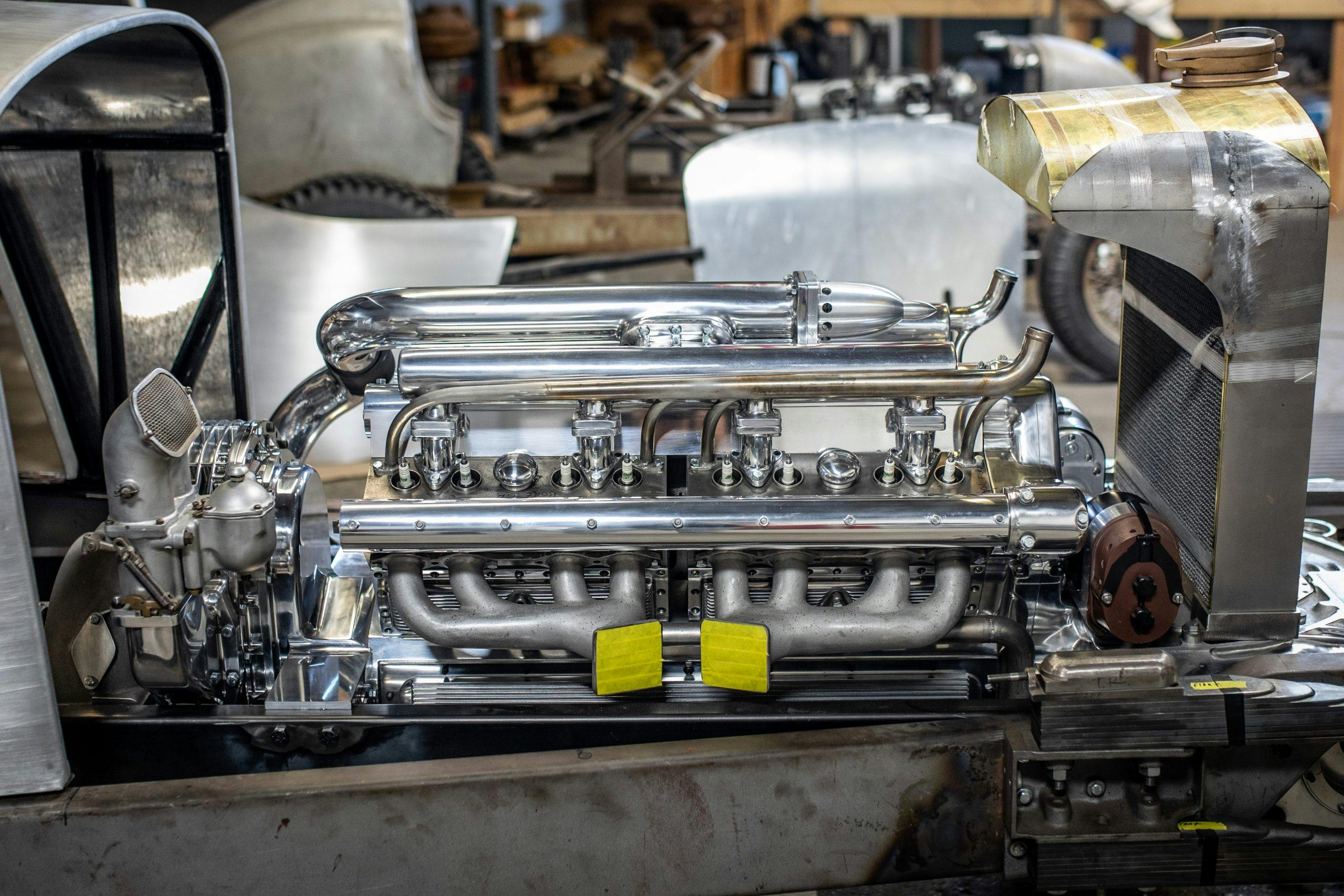

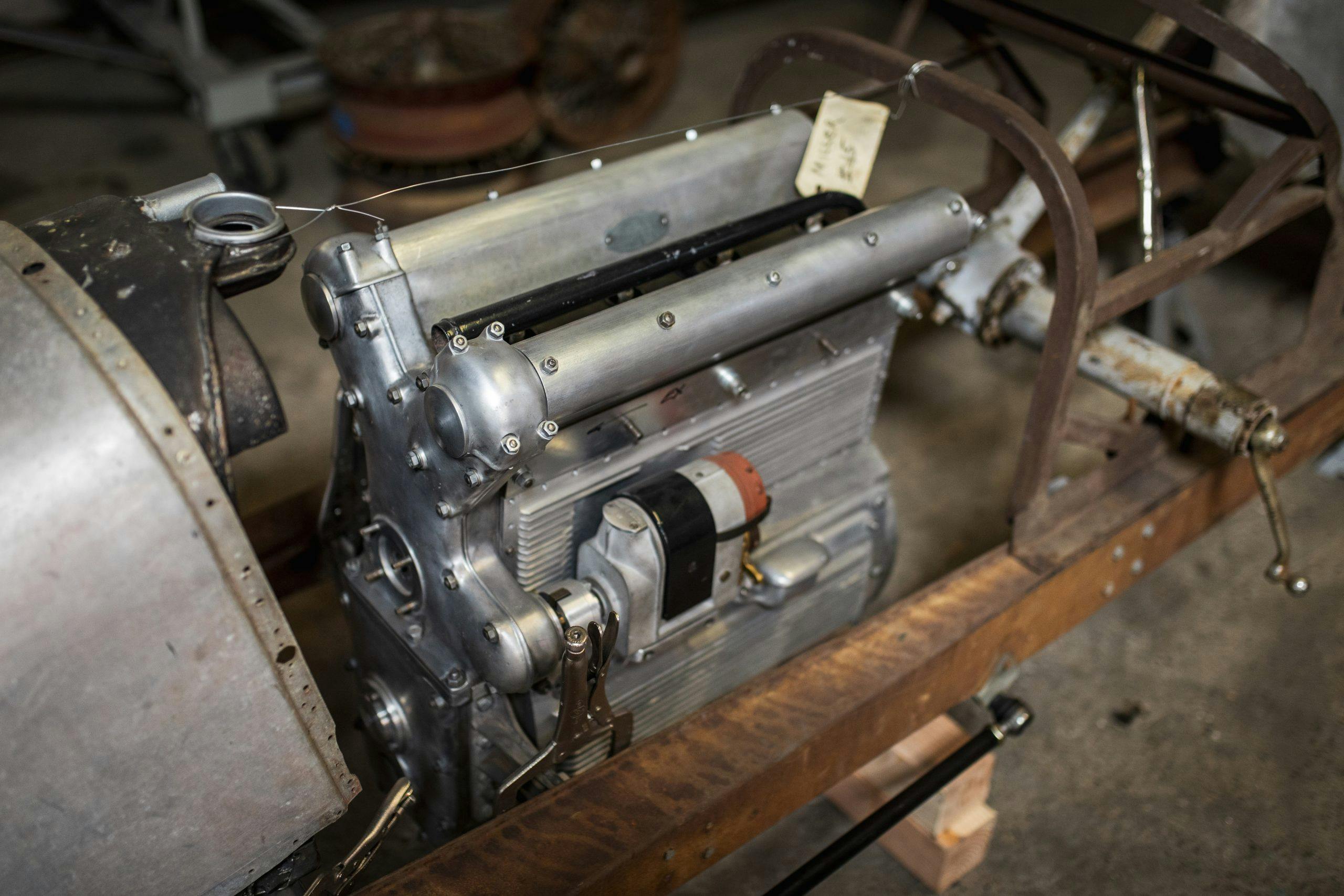

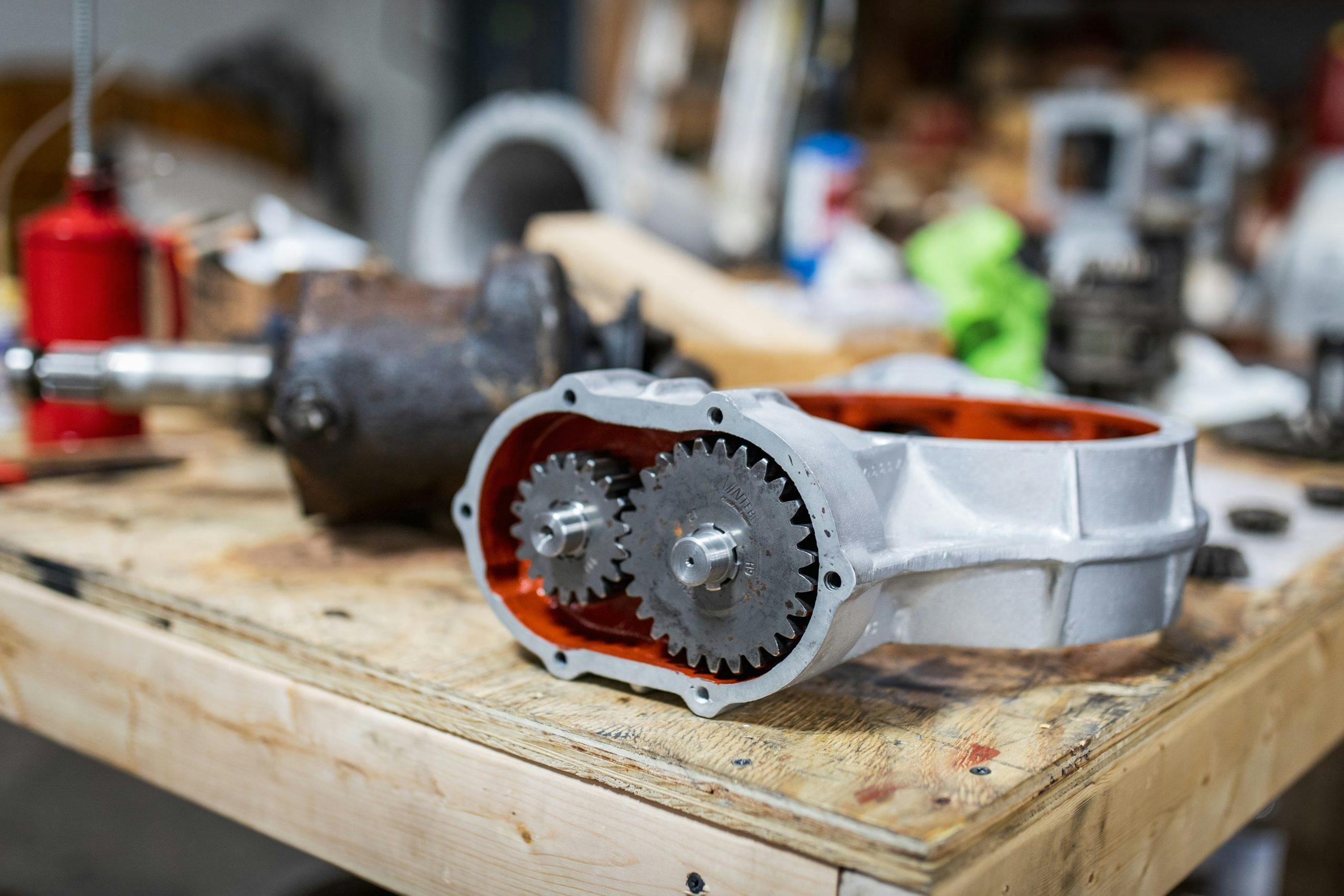

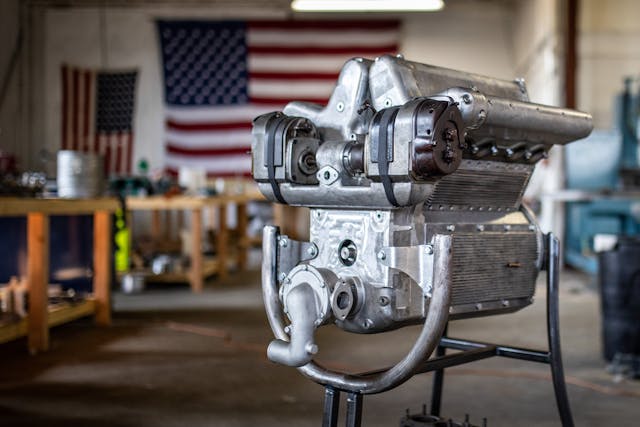

Years back, before the Miller mother lode came his way, Linn was asked to repair the ring and pinion on a Miller-Burden V-16 passenger car for a customer, using only factory drawings and a few black-and-white photos for guidance. Miller, the innovator known for his racing legacy, dabbled in building exotic street cars. The original car had been commissioned in 1932 by millionaire banker William Burden for $35,000, a staggering price at a time when families were lining up for soup and a V-16 Cadillac cost $6000. Harry Miller filed for bankruptcy mid-build, and the supercharged, all-wheel-drive coach was left in the hands of Fred Offenhauser. Offenhauser and team were able to finish the car, though the project was ultimately a failure. But the team’s attempt gave Linn, a longtime prewar aficionado, a keen appreciation for Harry Miller, and he grew more and more interested in acquiring Miller’s life’s work. “The Miller story is fascinating to me,” Linn says. “Miller, Offenhauser—they were incredible people, and their stories need to live on.”

Thanks to one document in particular, Linn and Shaw are doing their best to make that happen. As part of the Miller transaction, they acquired the rights to the Miller name, which means that any Miller car built out of EDL is a continuation car. “Our goal is to make replacement parts for original cars and complete a few that he was never able to finish,” Linn says. “We want to keep the Miller name alive for the next generation.”

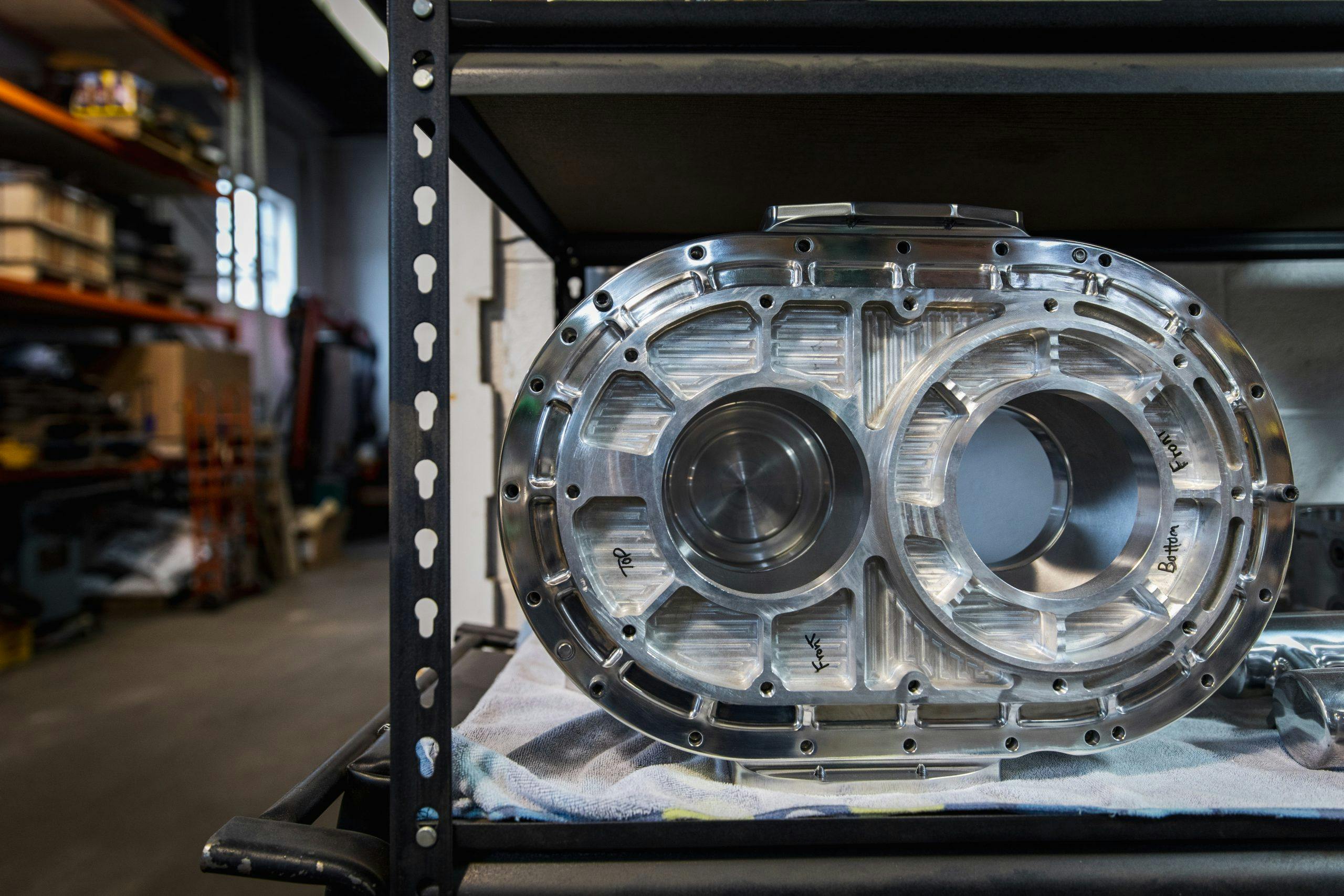

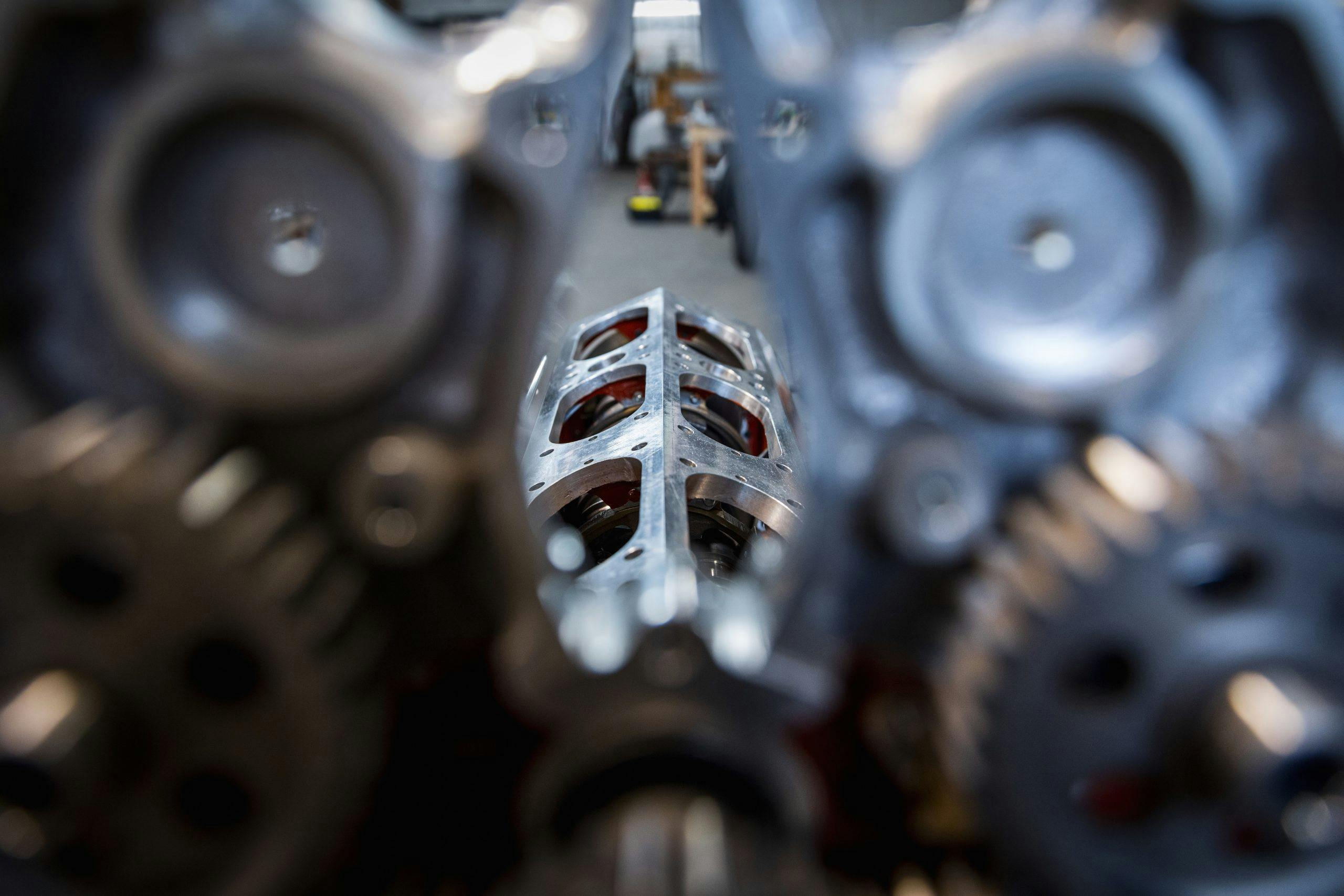

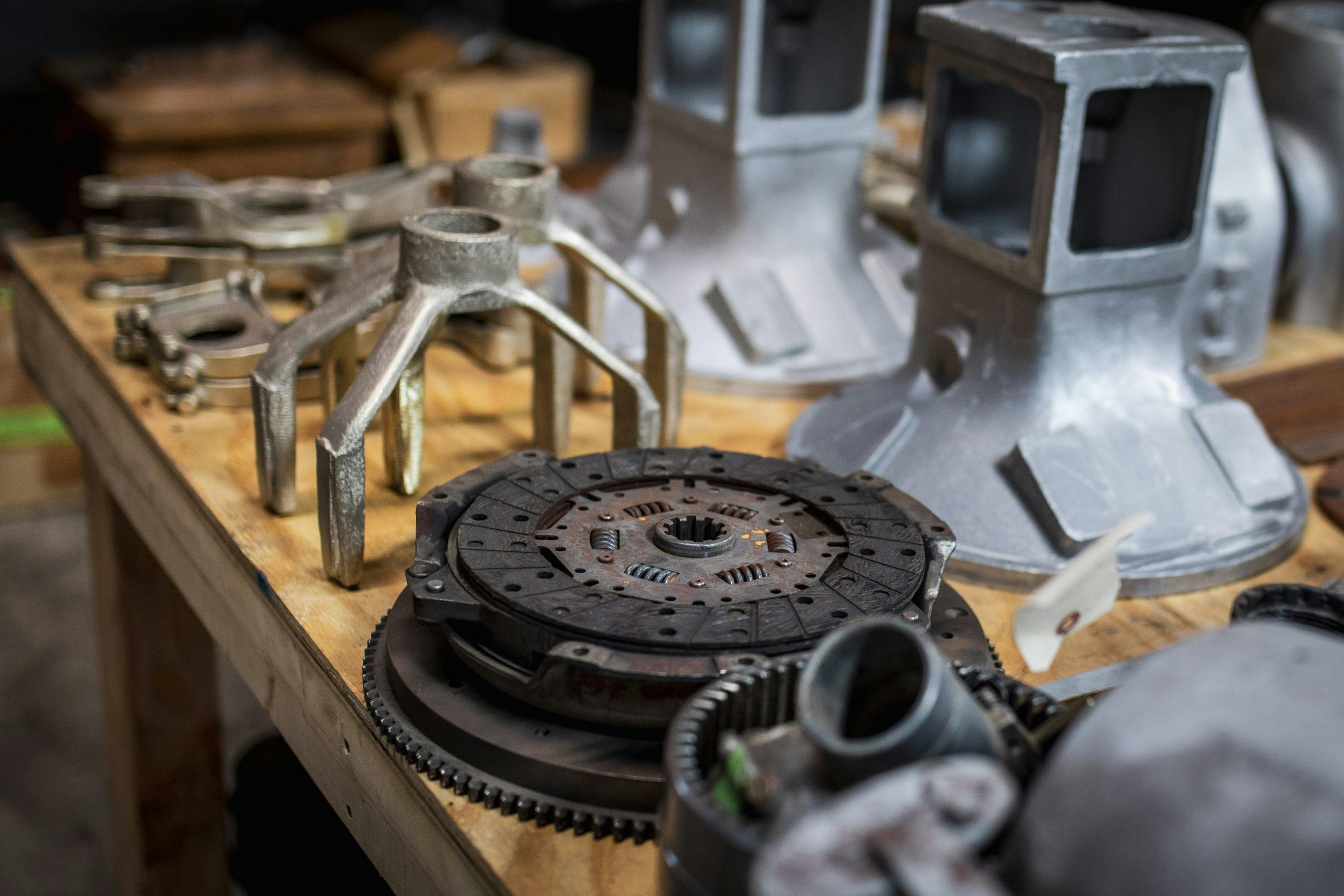

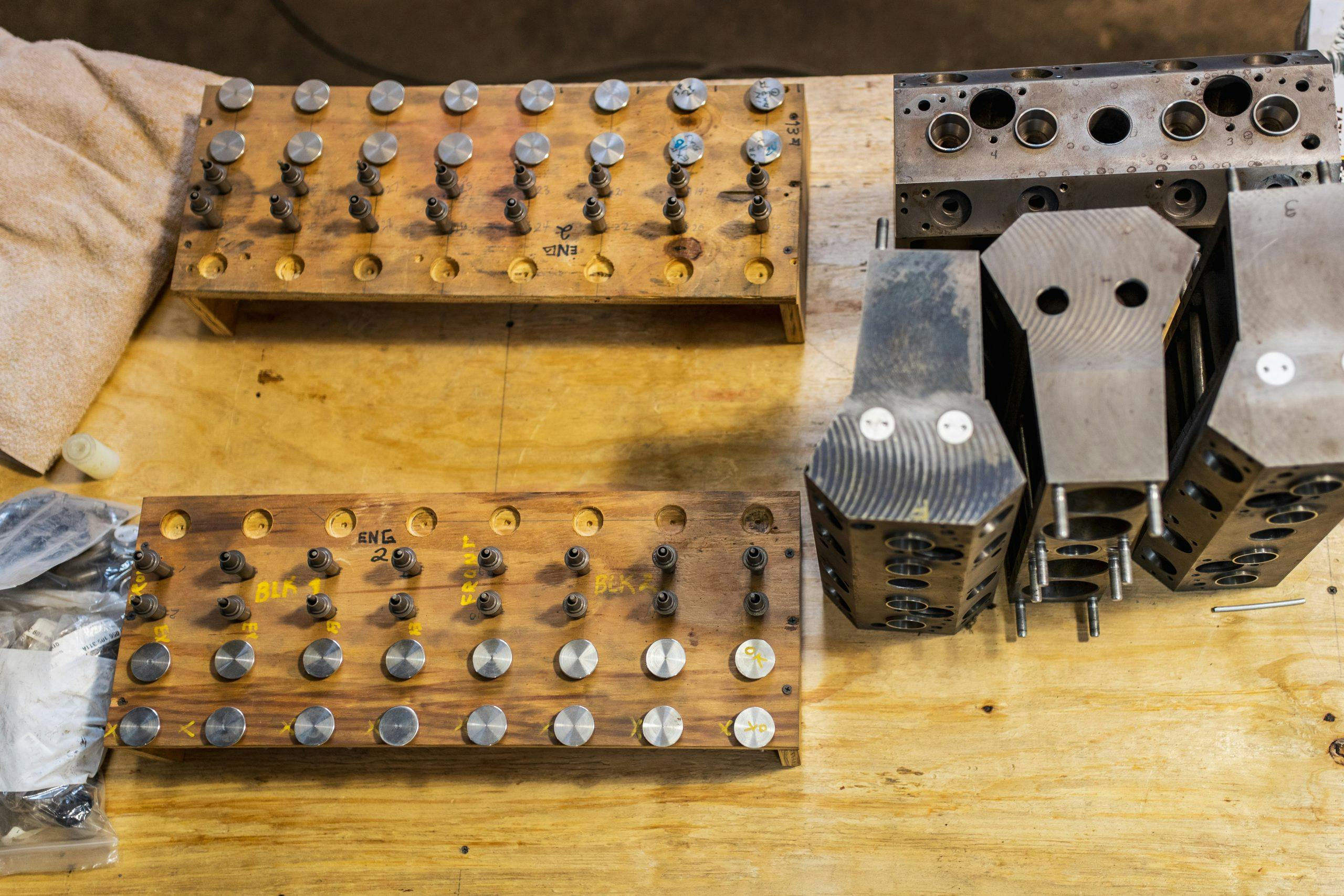

Many of EDL’s projects—including another V-16 pleasure car, which Linn acquired through a separate transaction—require parts that don’t exist in the real world. Instead, they live on drafting paper and in blueprints, and some only survive in reference photos. “We’re basically building ideas,” says Linn. For example, if the part needs to be cast, an EDL employee must first sift through the wooden patterns in the Miller inventory, currently a two-story grid of shelves and labeled boxes. Then they assess if the pattern requires any repair. If it does, they mail it out to a patterner. Once deemed a clean pattern, they mail it off to be cast at a foundry. It’s a far cry from opening the Speedway catalog and ordering a part. “Our biggest challenge is trying to get stuff made outside of the shop,” says Linn.

To complicate things even more, several machine shops have closed over the past 15 years. As a result, EDL has started making more parts and pieces in-house. “It’s a pretty daunting task, but for some reason, we want to do it,” says Linn. “We’re up to four lathes and two mills. And now we have a CNC machine—my son can run that.” Linn’s son Wesley is studying engineering at nearby Oakland University, and on his off days, you’ll find him at EDL. “I really enjoy working with my son,” Linn says. “Hopefully, someday he can take it all over.” Whenever that may be, it’s safe to say that EDL Services and the Miller name are in good hands for years to come.