Media | Articles

Sweet V-16: Cadillac’s most exotic engine

At a time when fours and sixes were the norm and V-8s were exclusive to luxury cars, powering a car with a 16-cylinder engine was as preposterous as doing so with a nuclear reactor. But in 1930, Cadillac introduced the world’s first V-16 to reinforce the meaning of its “Standard of the World” mantra. Competing engineers were astonished. Beyond its technical eminence, Cadillac’s new engine was stunning to behold.

Before this breakthrough, Cadillac’s arch rival, Packard, ruled the luxury-car roost with an arsenal of inline sixes and eights, plus its Twin Six, the world’s first V-12, introduced in 1916. By 1930, nearly every premium brand yearning for sales gains had a V-12 under development.

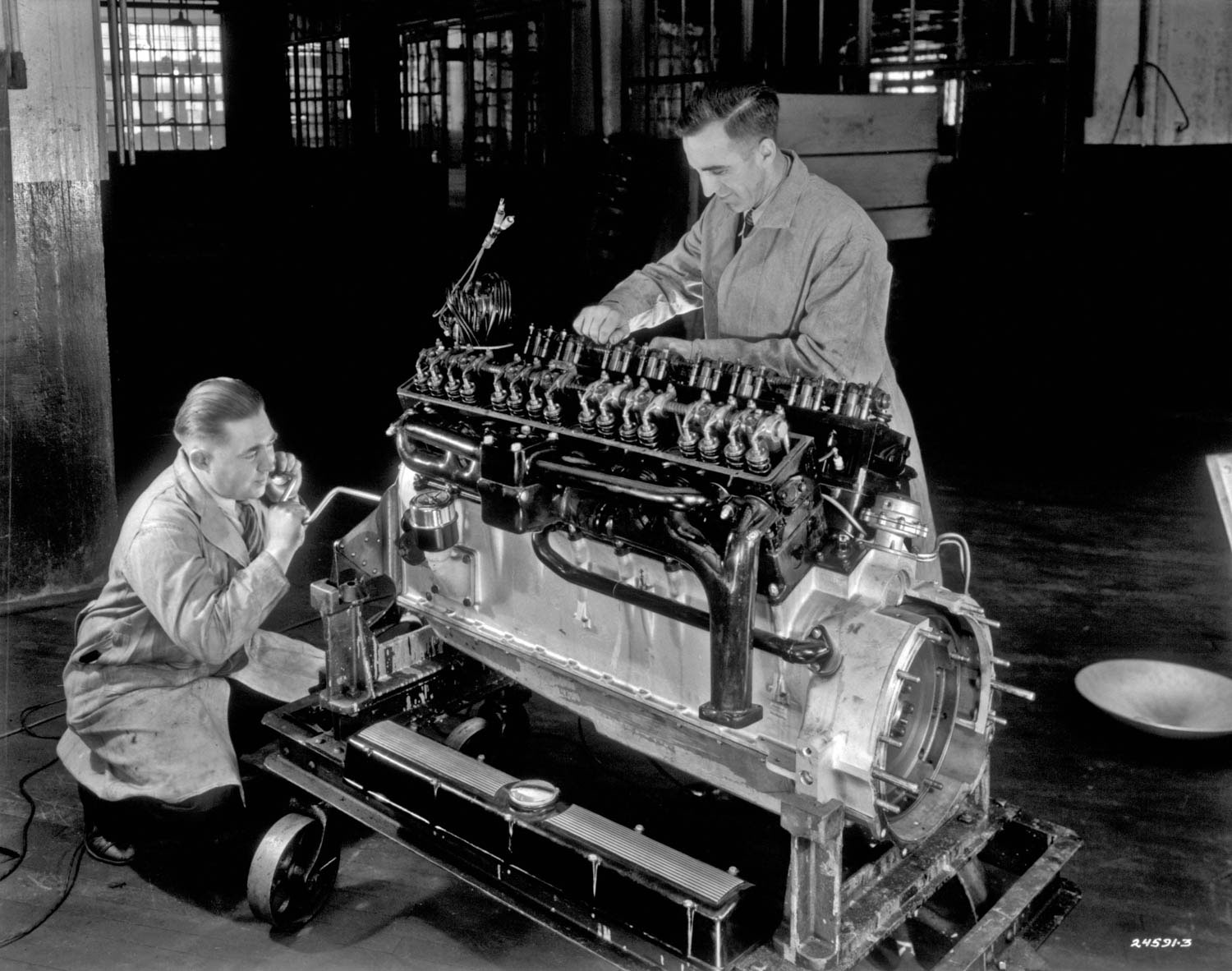

To topple Packard, Cadillac president and general manager Lawrence Fisher orchestrated a sensational leapfrog attack. Step one was to nab Owen Nacker from the Marmon Motor Company. This brilliant engineer not only guided V-16 design but also worked on new Cadillac and LaSalle V-8s, Cadillac’s V-12, the Hydra-Matic automatic transmission, and Allison aircraft engines during his 21-year career with General Motors.

Step two was to muster GM’s engineering, R&D, and styling resources to perfect the world’s first V-16. Fisher’s only miss was timing. Cadillac’s grandiose Series 452, powered by this epic engine, was announced shortly after the October 1929 stock market crash. Cadillac sold 2500 452s in 1930, then 750 in 1931, 300 in 1932, and 49 per year from 1935 through ’37. Price and volume were insufficient to turn a profit, but prestige at any cost seems to have been Cadillac’s true motive.

Advancing technical frontiers was standard Cadillac practice. Interchangeable parts, breaker-point ignition, the electric starter, and synchromesh transmissions were all invented here. Cadillac’s 1915 V-8 was the first of its kind built in volume. When it doubled the cylinder count a decade and a half later, GM’s premier brand also added a new overhead valvetrain with automatic lash adjustment.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Fisher and GM chairman Alfred Sloan established the auto industry’s first styling department. California coachbuilder Harley Earl’s use of clay modeling for experimental models had so impressed the GM generals that they hired him in 1927 to create the company’s Art and Colour Section. To refine the V-16’s appearance, fit, and serviceability, Earl and Fleetwood body designer Ernest Schebera built wood-and-clay models of the new engine for installation in prototype chassis.

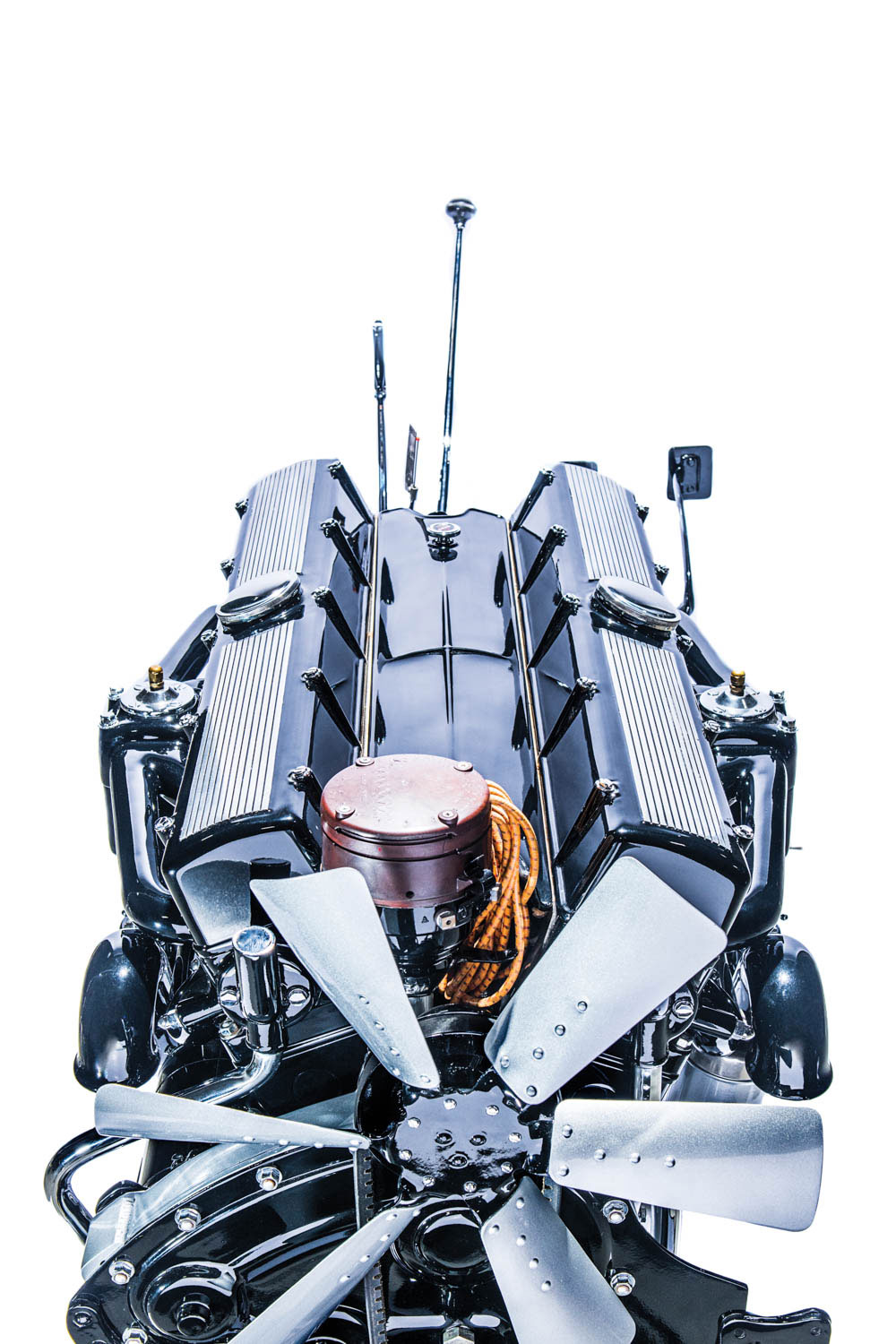

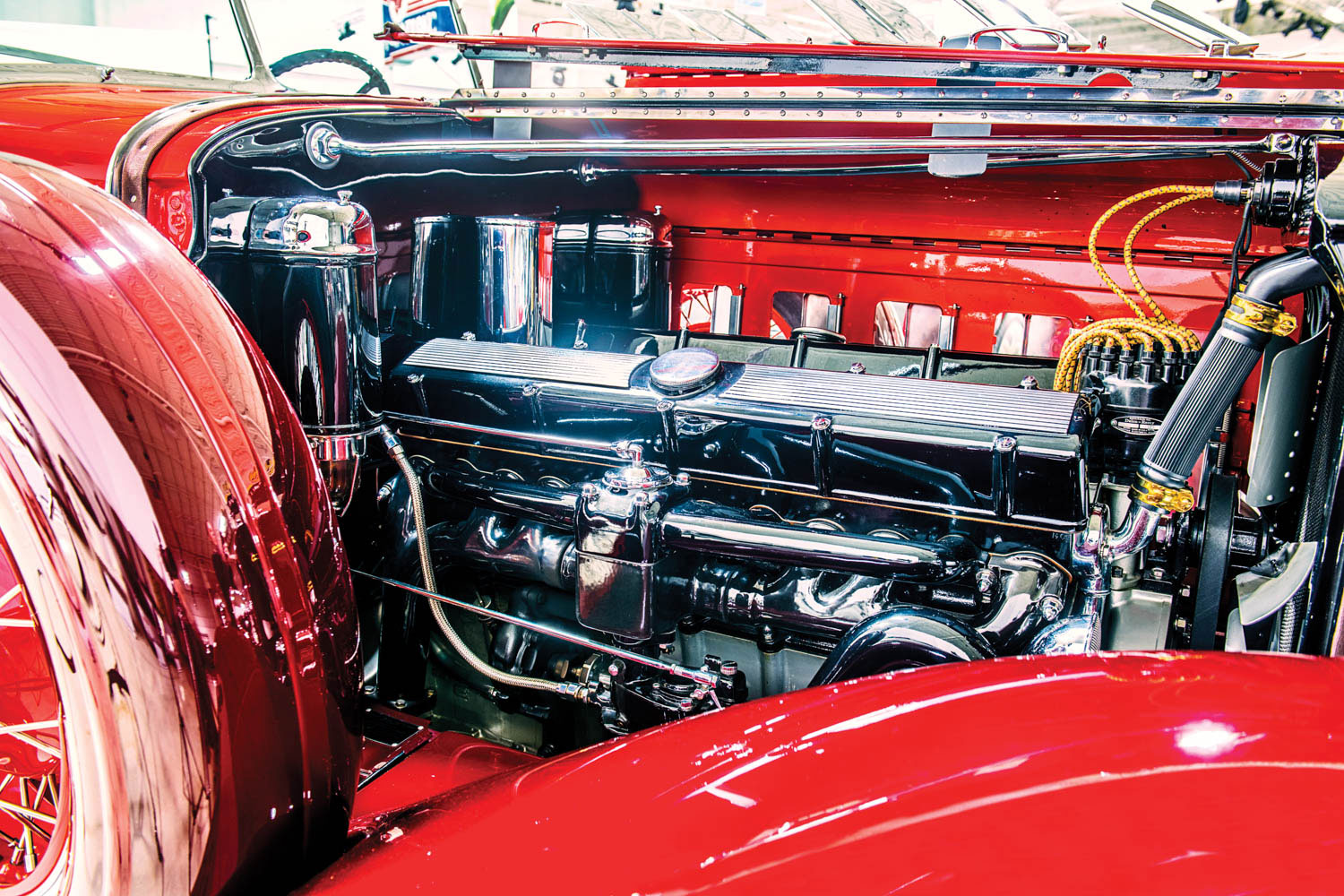

Earl’s fine design eye made Cadillac’s V-16 a visual masterpiece. Ignition wires and fluid lines were routed through the center valley beneath a smooth cover. Twin ignition coils were tucked into radiator-tank recesses. Exhaust manifolds bolted to the flanks received a beautiful black porcelain finish, and the adjoining intake manifolds and carburetor bodies were painted with shiny black enamel. The ribbed crown surfaces of the cast-aluminum valve covers were brightly polished, and chrome plating added sparkle to fasteners, the generator band, oil caps, the carburetor linkage, and a large vacuum tank located near the engine. Earl’s authority silenced the beancounters whimpering on the sidelines.

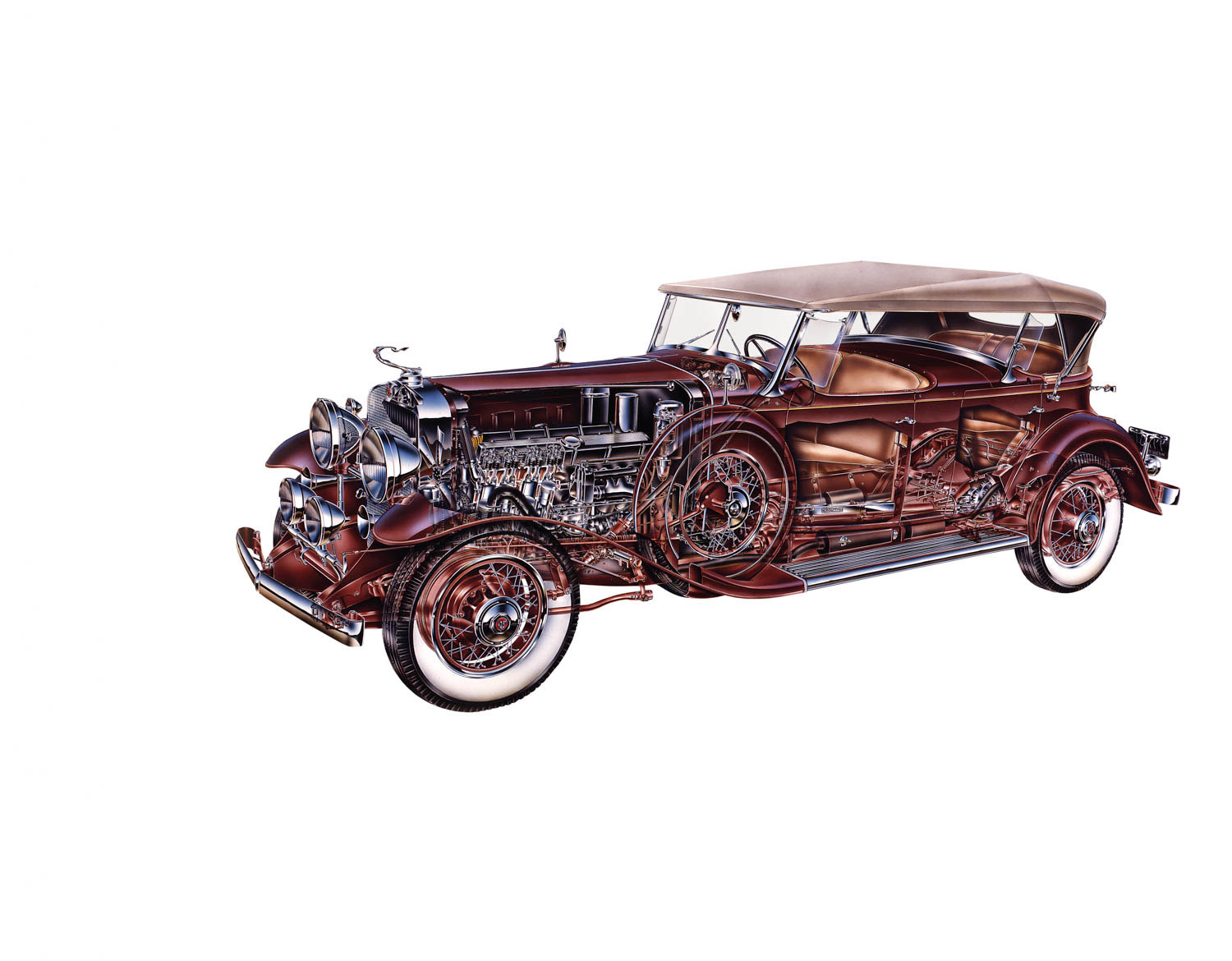

Cadillac chief engineer William Strickland explained the logic behind the 452-cubic-inch V-16 in a 1930 technical paper. In summary, a poll of “enlightened” engineers and Cadillac owners revealed that essential luxury-car attributes were smooth and quiet driving, strong acceleration, a high top speed, riding comfort, a beautiful appearance, and lavish appointments. To manage the Cadillac flagship’s eight-inch-longer wheelbase (to 148 inches), one-foot length increase, and 1000-to-1400-pound weight gain (some versions topped three tons), Strickland concluded that a 40-percent increase in power over the existing 96-hp, 353-cubic-inch V-8 was necessary. Merely increasing bore and stroke dimensions to achieve that power was deemed contrary to Cadillac’s high standards of smooth, quiet operation. Supercharging, which Duesenberg would soon deploy, was investigated but deemed suitable only for racing applications.

The ideal solution, according to Strickland, was to double the cylinder count while reducing bore and stroke dimensions, which would diminish the vibration attributable to the reciprocating motion of the pistons and connecting rods. Lighter moving parts reduced internal stresses while lowering lubrication and maintenance requirements, consistent with Cadillac’s pursuit of long-lasting engines.

Rounding down the V-8’s 3 3/8-inch bore and 4 15/16-inch stroke to an even 3.0-by-4.0 inches while doubling the cylinder count yielded 452 cubic inches, a 28-percent increase in displacement. Because higher compression yields significantly more power, to take advantage of the more detonation-resistant ethyl gasoline developed by GM researchers, the V-8’s 5.05:1 compression ratio was raised to 5.50:1 for the V-16. After considering vee angles as narrow as 25 degrees, Cadillac engineers settled on 45 degrees. That angle provided the best fit between the frame rails and even 45-degree firing intervals with an eight-throw crankshaft.

Although several V-16 design features are antiquated by today’s standards, it’s important to remember the engineering context of the 1930s. Following tradition, Cadillac bolted two eight-cylinder iron blocks to a separate aluminum-alloy crankcase—in other words, three separate castings versus the single, more complex block casting Henry Ford introduced for his 1932 V-8 (see “When the World Was Flat,” Hagerty, September/October 2018, page 110). The V-16’s 130-pound, fully counterbalanced, eight-throw, forged-steel crankshaft was supported by five main bearings and equipped with a harmonic torsional-vibration damper. Cast-iron pistons were fitted with four rings for optimal sealing and transfer of heat from their crowns to the cylinder walls.

Connecting rods were a significant 2.2 inches shorter than those used in Cadillac’s V-8. This, in conjunction with the shorter stroke, helped minimize the engine’s overall height. Shorter rods increase a piston’s acceleration when the piston changes direction at each end of its stroke, but smaller, lighter pistons and rods also yield less vibration. With 16 cylinders, overall balance is excellent, because the reciprocating force of one piston moving up in its bore is largely canceled by another moving down.

The cast-iron cylinder head was symmetrical to facilitate using the same part atop both banks. Internal intake and exhaust ports were gently curved for good breathing. One Cadillac-built, single-throat updraft carburetor supplied each bank of cylinders. Gasoline was drawn from the tank by an engine-driven vacuum pump and stored in reservoirs mounted on the firewall. Fuel flowed from the reservoirs to both carburetor float chambers by gravity, and intake and exhaust manifolds were bolted together to use exhaust heat to help vaporize the fuel. Dual exhaust pipes were standard equipment.

Cadillac’s 452 V-16 had a deep-skirt crankcase that provided a stiff, quiet foundation. A single camshaft opened one intake and one exhaust valve per cylinder via roller cam followers, pushrods, and rocker arms.

The coup de grâce was an automotive first: hydraulic valve lash adjusters. Each rocker arm was supported by an eccentric (oval-shaped) pivot. Rotating that pivot while the valve was seated eliminated undesirable clearance (lash) at pushrod, rocker-arm, and valve-stem locations. This made the engine quieter while canceling the need for valvetrain adjustments during initial assembly and service. Pressurized engine oil rotated the pivot and lubricated the rocker arms and their contact points.

The beauty of a 16-cylinder engine is one power pulse every 45 degrees of crankshaft rotation (versus 90 degrees for V-8s and 180 degrees in a four-cylinder engine). Smaller, more frequent wallops from the pistons to the crank spin the flywheel with less herky-jerky rotation, the key to velvety acceleration and cruising. Think gas turbine versus paint shaker. Following its V-16, Cadillac achieved supreme smoothness and adequate power with 12, then eight, then fewer cylinders without incurring the weight, friction, consumption, and cost penalties that came with 16 cylinders. Of course, that ignores presentation value. Nothing merits a permanent pass to the Pebble Beach greens quite like two 45-inch-long cylinder banks filling the engine bay.

Strickland’s output curves showed 300 or more pound-feet of torque from 500 to 1900 rpm and a peak torque of 320 pound-feet at 1400 rpm. The maximum 165 horsepower was available at a modest 3400 rpm. Strickland asserted that the valvetrain and ignition systems still worked at speeds “considerably exceeding 4000 rpm.” In proving-ground tests, the largest seven-passenger Cadillac sedans were good for 84 to 91 mph, depending on axle ratio; the lighter, lower-drag V-16 roadsters easily topped 100 mph. The only faster contemporaries were Duesenberg’s Model J, capable of 119 mph, and the super-charged SJ, allegedly good for 140 mph.

Before 0-to-60 mph became a performance measure, Cadillac’s V-16 was clocked accelerating from 10 to 60 mph in 21.1 seconds. Fuel economy of 8 mpg was typical, and a team of three adventurers averaged a quart of oil consumed every 150 miles on a 10,000-mile international trip. An English road tester reported “an engine so smooth and quiet as to make it seem incredible that the car is actually being propelled by exploding gases.”

Cadillac’s own “listening test” specified nothing louder at idle than the click of the ignition points. John Bond, who became Road & Track’s publisher in 1949, wrote, “At cruising speeds, the only audible sound was from the fan and the two carburetors pulling air through their large air horns.”

Following its New York auto show debut in January 1930, initial orders exceeded Cadillac’s fondest aspirations, in spite of dire economic circumstances and prices ranging from $5350 to $9200 (when Ford Model As cost between $435 and $650).

Eight coachbuilders, including Pininfarina, offered a bewildering 54 model variations atop a majestic 148-inch wheelbase with a choice of flat, vee-shaped, or sloped windshields. Available interior trim included doeskin suede broadcloth, Venetian mohair, Bedford cord cloth, and 15 shades of leather. A monogrammed lap robe matching the upholstery cost $80. Two vanity cases were offered, one with an eight-day clock and one with a “cordless” cigarette lighter and two ashtrays.

Chassis hardware was crude by today’s standards. Cadillac’s “safety mechanical” brakes were cable-actuated drums with a vacuum booster to reduce pedal effort. The Series 452 had wooden-spoke wheels; steel discs and painted or stainless-steel wire-spoke wheels were optional. A “knee action” independent front suspension didn’t replace the rustic solid front axle until 1934. An automatic transmission and power steering were far in the future.

What stunted demand for V-16s more than the Depression’s bank defaults and breadlines was Cadillac’s introduction of its nearly-as-smooth Series 370 V-12 models in the fall of 1930, with 11 body styles and prices starting at $3795. Packard, Pierce-Arrow, Lincoln, and Franklin all responded with new V-12s of their own. Marmon’s V-16 arrived in April 1931, just in time to drive that esteemed brand out of the car business.

Cadillac’s V-16 Series 452 served perfectly as the basis for Harley Earl’s first concept car. His Aerodynamic Coupe, constructed for display at the 1933 Century of Progress in Chicago, was the ultimate four-passenger indulgence, with flowing fenders, thin chrome window moldings, and a gorgeous fastback roofline. Eight similar V-16s were produced for sale from 1934 through 1937, and Earl’s design strides helped modernize the appearance of successive GM production models.

Instead of bidding its V-16 goodbye at the end of its natural life, Cadillac shocked the industry by introducing a Series 90 replacement in 1938. This V-16 was a less exotic, more practical (read “cost effective”) poke in the eyes of luxury-class survivors Lincoln and Packard. It used a single-piece cast-iron block with a 135-degree vee angle topped by flat heads instead of overhead valves. Sharing many V-8 parts, this engine featured 3 1/4-inch bore and stroke dimensions yielding 431 cubic inches and 185 horsepower at 3600 rpm. Cost saving over the previous V-16 came with the reduced parts count, a six-inch-shorter length, and a 13-inch height reduction—for 250 fewer pounds. Series 90 prices ranged from $5140 to $7175; 508 were sold from 1938 through 1940, when another recession crippled the U.S.

Few shadowed Cadillac into this exotic corner of engine design. Marmon sold 400 V-16s from 1931 to 1933. Peerless cried uncle after constructing three V-16 prototypes. In the modern era, Cizeta Moroder coupled two Lamborghini V-8s together for a short run, and Bugatti built 450 Veyrons and (a planned) 500 Chirons powered by turbocharged W-16s. Maserati, Miller, Auto Union, Alfa Romeo, and BRM had varying degrees of success racing 16-cylinder cars.

Chief engineer Ernest Seaholm succinctly summed up the V-16’s place in Cadillac history: “This dream of the Roaring Twenties materialized at the time the bottom dropped out of the stock market. Advertised for the 400 wealthiest Americans who went into hiding, it instead found empty pocketbooks. Be that as it may, it was an outstanding piece of work.” What Seaholm didn’t acknowledge was that V-16s were never profitable. This was a saber-rattling exercise, part of Cadillac’s grand strategy to enrich its prestige while maiming its enemies. Mark that “mission accomplished.”

The article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe to our magazine and join the club.

Thank you for the memories I miss my car the first of the third design, but I long sold her along time ago, I would gladly buy any Cadillac lassale or hardtop V16

Thank you for the memories I miss my car the first of the third design, but I long sold her along time ago, I would gladly buy any Cadillac lassale or hardtop V16 I wish I could remember how long she was and how much has she took

How much gas she took