Media | Articles

CadMad: The anatomy of a Ridler winner

CadMad is a hot-rod fever dream of an atomic-age family wagon that looks like 1200 gallons of chilled rosé trying to go supersonic. It has yards of metal in it from a hyper-rare 1959 Cadillac and some scraps from a 1956 Pontiac Safari. But otherwise, it is all hand-formed, pearl-coated, wet-sanded, chrome-plated, and turbo-injected custom perfection.

Jordan Quintal II remembers the first phone conversation about CadMad. “Steve Barton contacted me and said he had a Cadillac that he wanted to build into a station wagon. ‘Can we do it?’ I said, yes, we can do it—we can do anything with enough time and money.” Quintal remembers the second conversation with Barton, too. “He said, ‘I want to do a Ridler car.’” Quintal knew that when the word “Ridler” is spoken, everything changes.

The Don Ridler Memorial Award trophy has been handed out every year at the Detroit Autorama hot-rod show since 1964. A gleaming silver cup perched on a flying arc of perforated aluminum mounted to a large black plaque, the trophy is the Nobel Prize of hot-rodding. The rules are dead simple: Any car from any year is eligible, so long as it is operable and has never appeared anywhere previously. Winning a Ridler once in a lifetime is all most builders ever dare aspire to. Quintal had already built two contenders, a ’56 Ford pickup that made it into the final judging round—which Autorama calls the “Great Eight”—and a ’49 Chevy coupe named “M-80” that took the Ridler in 2001.

That was the last year of the old era, the year before Chip Foose arrived with a ’35 Chevy dubbed “Grand Master” that blew the level of craftsmanship required to win (as well as the price) straight through the roof. It costs clear over a million to win a Ridler now, but Quintal has been around. He owns Super Rides by Jordan, a slightly shaggy industrial unit filled with carcasses of old cars and situated in the beating heart of the hot-rodding enclave of Escondido, California. Now 70, Quintal started building cars as a teenager, and he knew instantly the level of insanity that Barton was suggesting. “Every square half-inch has to be perfect,” he says.

Some shops won’t touch Ridler projects because of the way they eat time and rack up seven-figure bills. In the months before the show, the car consumes the entire shop; everything else stops. On show weekend, the pressure is tectonic. Owners who have waited years while writing mountains of checks are target-fixated on the prize. You can only debut at Autorama once—every car gets just one shot at the title. Losing owners sometimes don’t pay their bills, and shops say they often don’t make much—if anything—on Ridler cars.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

“It’s not for everybody,” says Quintal, with supreme understatement. “You have to have the right owner.”

Stephen F. Barton seemed to be the right owner. The Las Vegas–based scion of an Oklahoma appliance-rental empire, Barton designed his own hot rods and had 37 cars in a collection underneath a 16,000-square-foot mansion filled with antiques and big-time art. He had the means and the enthusiasm, but the proposed project was enormous: The donor car was 19 feet long and had more than 5000 pounds of steel, iron, and glass in it, much of which would need to be cut out or heavily modified. Quintal had already been there, done that, but like everyone who works in the hazy borderland between machinery and art, he felt the magnetic pull of the Ridler, of dazzling everyone with something new.

He told Barton, “OK.” CadMad would devour $2 million and the next 16 years of his life.

The project was unique from the get-go, since the starting point was no ordinary Cadillac. In 1959, GM contracted with the Italian design house Pininfarina to build a special four-door Eldorado Brougham with unique sheetmetal and trim. The special Eldo eschewed the taller fins and dual-bullet taillamps of the other ’59s for the less flashy dorsals that later appeared on all 1960 Cadillacs. Barton owned two of the Pininfarina Cadillacs, which retailed new for $13,075, almost twice the sticker of a ’59 Biarritz convertible.

CadMad is the 85th Brougham built out of a total of just 99 cars. It arrived at Quintal’s shop in 2002 and immediately got stripped and acid-dipped. Quintal’s plan was to gut the body, shape the shell into the wagon form Barton had in mind, and then build a frame and powertrain to go underneath. He put his then-teenage son, Jordan Quintal III, to work welding up the body. “This was his college education,” Quintal says.

CadMad was essentially proportioned around its hood and its top, which kept their stock dimensions while almost every other dimension of the car changed. “We didn’t want the top to look small compared to the rest of the car,” says Quintal, “or widen the top, because it would look like it was hit on the head with a pan.” So the car’s overall width shrank by 4.5 inches, which doesn’t sound like much but is akin to shrinking your house by 4.5 feet. All of the huge fenders had to be sectioned, trimmed, and rewelded. The front bumper and grille, which have almost 300 pieces between them, had to be cut and seamlessly sewn back together. Ditto the rear trim, which like the rest of the Cadillac’s exterior bits are unique to the 99 cars that Pininfarina built. Each of the irreplaceable jet-afterburner taillight housings were cut down the middle and sectioned to be narrower, and new lenses had to be fabricated from scratch.

The windshield base slid rearward, the doors were extended aft by 6 inches, the rear doors were tossed, and the body was sculpted with metal to fill the holes. The overall length of the car was clipped by 18 inches, and the Quintals also chopped not just the roof but the rest of the body as well, sectioning the whole car around its midriff to remove 2 inches of height. A clean-enough 1956 Pontiac Safari wagon hulk was found, and the Quintals pruned off the top and sold the rest.

At the end of nearly two years of cutting and welding and hammering and rolling and filling, the Quintals had basically roughed together the shell of a 1959 Cadillac station wagon in 7/8-scale. Now the work began underneath.

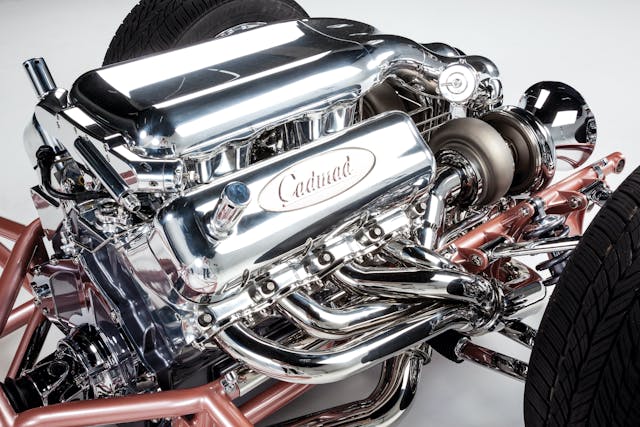

Barton’s vision for the engine was to keep the car’s lineage pure Cadillac by shoving together two 1990s Northstar V-8s to make a V-16. The plan was to turn the aft Northstar backward to mate the two mills at the crank, and a hot-rod engine builder in Pahrump, Nevada, was hired to do the job. Meanwhile, the Quintals turned their attention to the tubular steel frame. The engine would lay in a cradle at the front while a live prop shaft would turn the rear-mounted torque converter inside the Corvette 700R4 automatic transmission. The thicket of exhaust tubing would flow around the components, strategically anchored to appear as if floating on air. It would be Quintal’s first build with a transaxle, so the learning curve was steep. When we asked if there were computer drafting files or drawings of any kind, Quintal simply pointed to his forehead. “It’s all in here.”

A Ridler builder intent on winning strives to make the car look “clean,” as if it runs on space waves and is held together by fairy glue. Thus, much of the agonizing detail work goes into hiding things. False walls are built to shield the plumbing and wiring. Fasteners screw into hidden captive nuts, their heads vanishing behind seamless plugs or overlapping sheetmetal. Welding fillets are painstakingly sanded and shaped to disappear. Hinges are tucked away out of the light. As in any theater production, the builder just wants the audience to see the show, while the fluids and fasteners and electrons labor like stagehands behind the curtains.

CadMad was fully assembled and fully disassembled too many times for the Quintals to remember. Everything had to be tested and retested for assembly and fit before painting. The younger Quintal designed and fabricated all of the window trim from scratch so that screw heads wouldn’t be visible; then he had to figure out how to install it once the paint was in place. They invented a through-bolt system for the mostly hidden rear wheels so that the wheels could be removed by pulling the bolts inward from underneath the car.

To preserve the classic look of the original steering wheel, they machined a new one from billet aluminum and resized it to fit the rest of the car. The Quintals made the dash and stacked center console from metal, just playing around with shapes until it looked right. The custom gauge pack from Classic Instruments cost $7000, and the seats are a pair of re-sculpted and reupholstered thrones from a modern Cadillac CTS-V. Master pinstriper Lyle Fisk, a contemporary of Von Dutch, painted the “wood trim” on the dash and doors to match the slab of exquisite butcher block lining the cargo area, which the Quintals had finished to a glassy brilliance.

There were problems. The builders sank $3000 into a paddle-shift concept that didn’t work. The upholsterer managed to scratch the $3900 windshield, so in went a new one. And then there was the engine. After three years, the guy hired to marry the two Northstars had yet to produce anything. At that point, Quintal urged Barton to abandon the vision of a modern V-16 and consider something more conventional. Barton swallowed his huge disappointment and agreed, if only to keep the project moving. Tom Nelson of Nelson Racing Engines in Chatsworth, California, committed to building CadMad an appropriately outrageous motor. The 632-cubic-inch big-block V-8 feeds from two giant turbos and has parallel injection systems to deliver pump gas or, when goosed, racing fuel. The engine cost $97,000 after all the shouting was over, but at least it fit in the long hole meant for the V-16 once the Quintals laid out the turbos like twin forward-facing bazookas.

After experimenting with shades of blue, Barton and Quintal settled on Fawntana Rose, a color that was close to a stock ’59 Cadillac hue. All the parts were moved to a professional booth and painted by Quintal at the same time so the temperature and humidity would be identical, and thus so would the paint shade. The pearl-coat paint itself wasn’t too expensive—“I think it was four grand,” recalls Quintal—but with hundreds of hours of hand-sanding and finishing in every corner, including the frame, the floor, the doorjambs, the wheel wells, and the backside of every panel that might be visible, the paint job ran to a staggering $300,000. The amount of work is “like painting five nice cars,” says Quintal.

The judging at the 67th Detroit Autorama started on Wednesday, February 27, 2019. Over the next four days, a team of seven judges undertook the task of winnowing some 30 Ridler candidates down to the Great Eight, and finally down to a winner. “One thing that stood out about CadMad to me was that not one area of that car was left untouched,” says Butch Patrico, president of the Michigan Hot Rod Association. “The underside was as nice as the top. Also, it was such a large car. When you take on a build like that, your margin of error is huge; it’s very different to build a car that big.”

The following Sunday, CadMad was crowned, but Steve Barton wasn’t there. Barton died in January 2018 at the age of 76, having never driven CadMad or seen it completed. Craig Barton said his brother asked him before he died to finish the car, and Craig honored his brother’s wish, arriving in Detroit to see CadMad for the first time. “I was stunned by the enormity of the undertaking. It was gorgeous, way beyond what I expected. My regret is that Steve won the award that he wanted to win his whole life but didn’t live to see it.”

Back in Escondido, the Quintals watched from afar as CadMad crossed the block at Barrett-Jackson’s Scottsdale auction for what seems like an absurdly low price of $302,500. Quintal just shrugged. “It’s worth exactly what someone is willing to pay for it.” He and son Jordan have plenty of new projects. In the work bay where CadMad came together, there’s a wild pro-street Camaro project in pieces, and other half-finished cars crowd the shop. Would they do another Ridler? Quintal shakes his head. “I don’t want to do another one.” Then he points at his son. “He can.”

CadMad 1959 Cadillac custom

Donor cars: 1959 Cadillac Eldorado Brougham, 1956 Pontiac Safari

Engine: Turbo-charged V-8, 10,357 cc

Power: 1025 hp @ 5800 rpm

Torque: 979 lb-ft @ 4600 rpm

Build cost: $2 million

2020 auction sale: $302,500

The custom car that cured me of any interest in custom cars.

Agreed. Two million $ … huh?