Media | Articles

8 unusual cars with unexpected origins

Cars aren’t always the first thing a manufacturer lights upon when building a business. Some, like Honda and Suzuki, diversified into cars via motorcycles, while others began in aviation, such as Bristol or Saab. Others were spun off existing businesses—step forward, Citroën and Volvo—and became successful there too.

But there are other avenues still. Sometimes, economic or extraordinary circumstances require expertise beyond that of traditional car maker. Manufacturers may approach designers with a specific brief; others may tout for business hoping to change the face of transportation as we know it.

Some surprising names have dabbled in cars in the past 120 years, but for every Ford, Ferrari, or Fiat there are others that have stayed in their lane, having realized the sums didn’t add up. Think Bulgari, Miele, and most recently, Dyson. Not every attempt is successful, but we salute those that were. The history books would be duller without them.

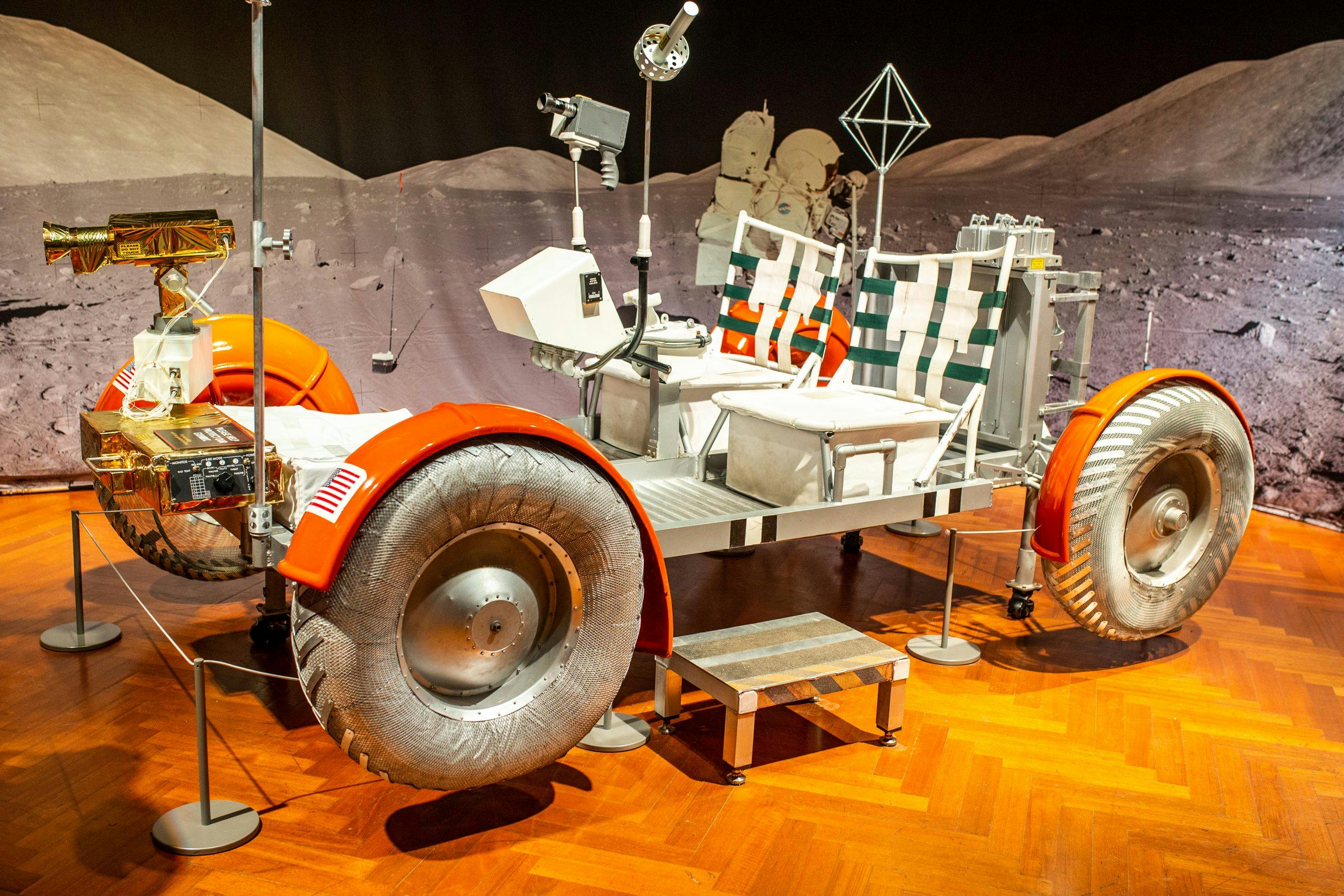

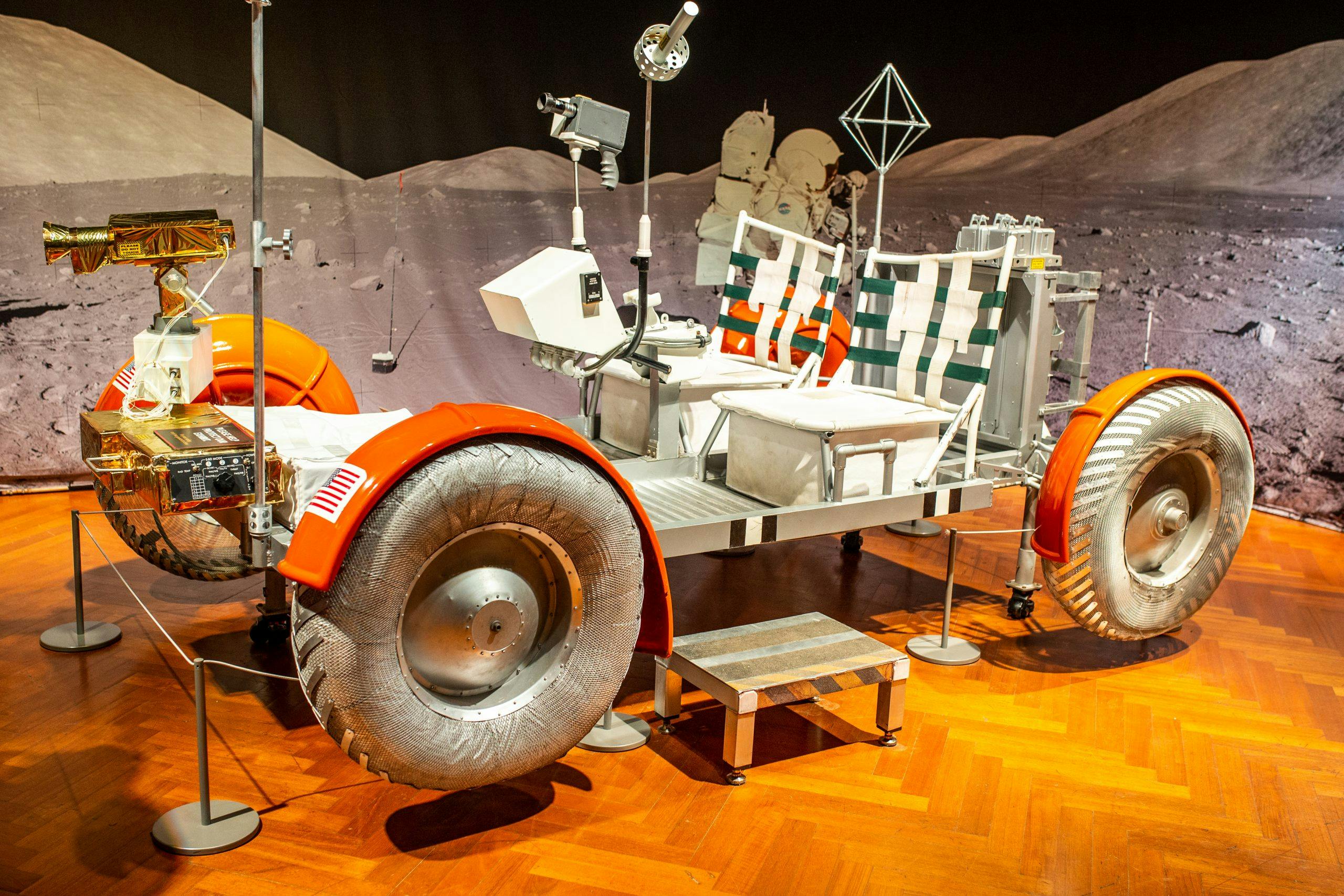

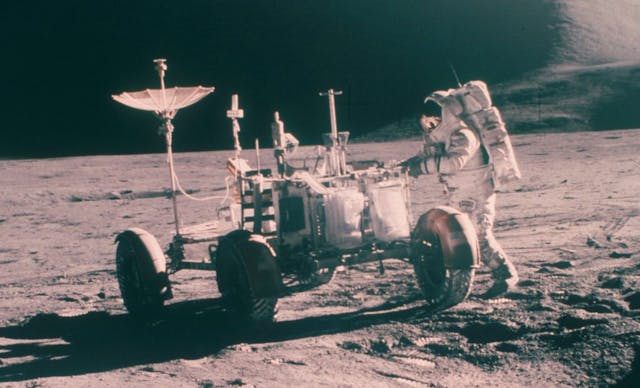

Boeing Lunar Roving Vehicle (1971–1972)

Cars allow greater mobility, and the same is true on the Moon.

When NASA wanted more from its costly Moon landings after Apollo 11, specifications were sent to manufacturers. Boeing, Bendix, Chrysler, and Grumann submitted proposals, with the first landing the job of building it after earlier proposals for heavyweight, long-distance vehicles were rejected.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

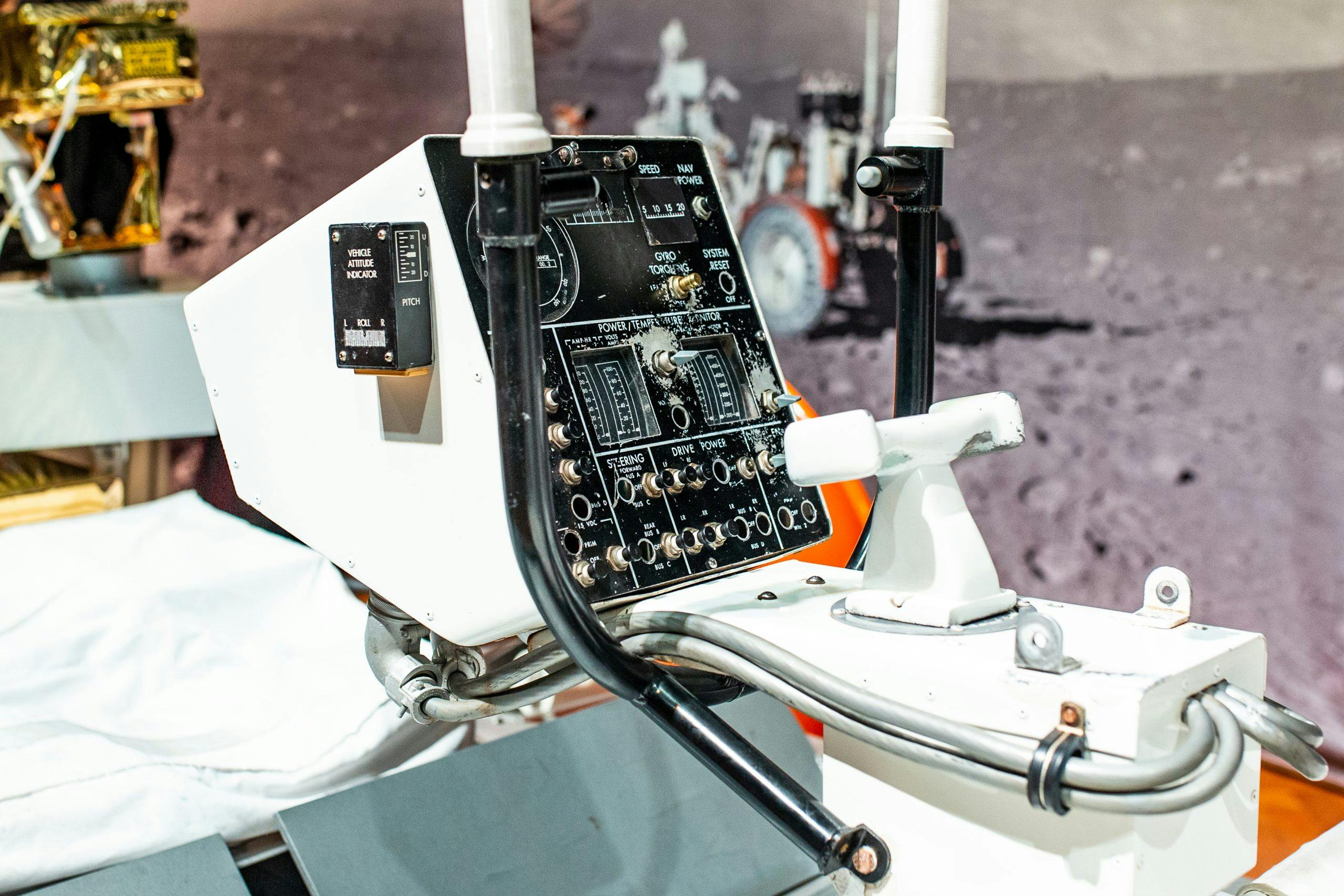

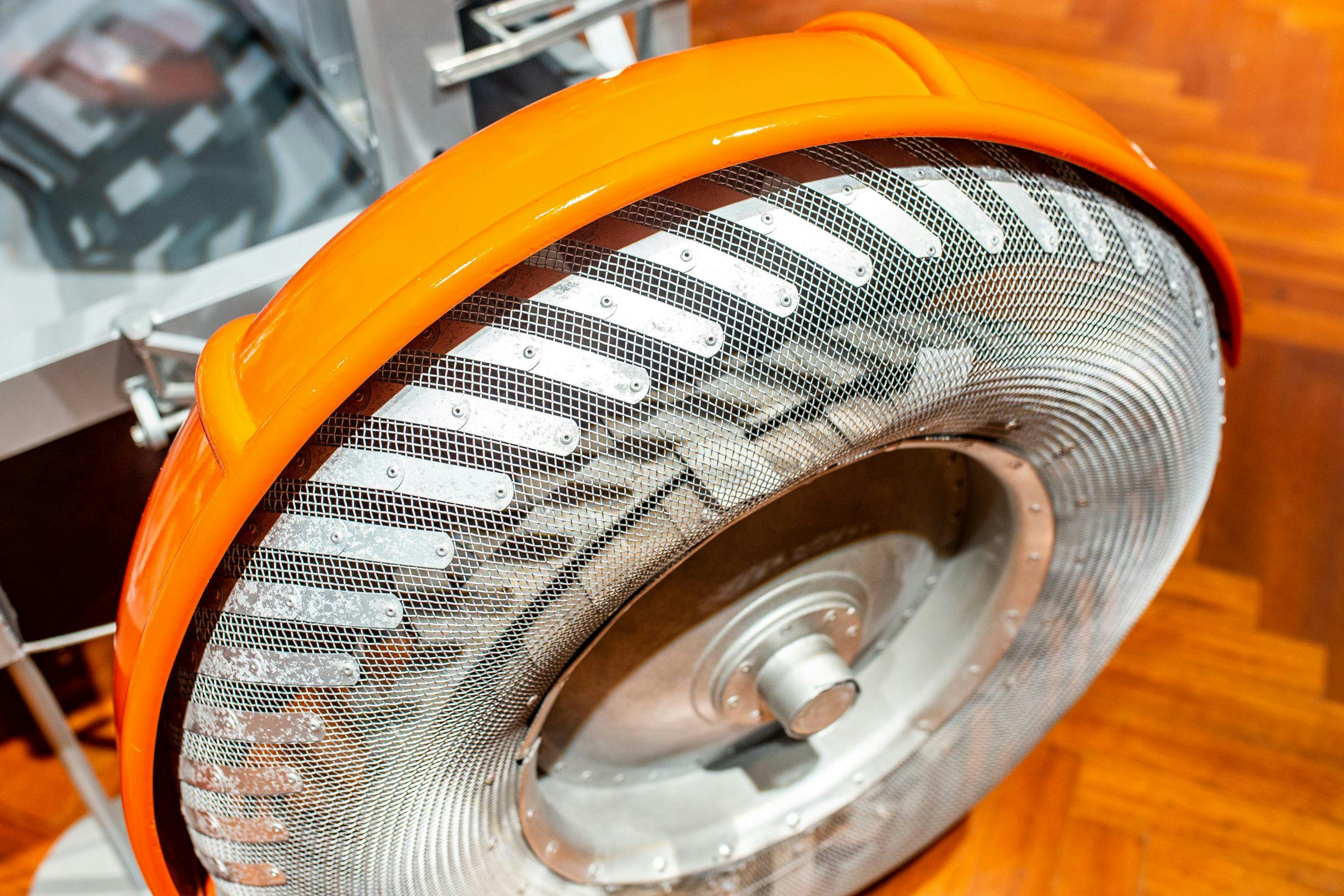

That’s not to say Boeing was responsible for the LRV completely: General Motors’ Defense Research Laboratories designed and built its suspension, mesh wheels, and electric motors, situated one per corner. The LRV was all-wheel-drive and had four-wheel steering for maximum maneuverability.

Owing to weight and space restrictions, it was light—very light, a motorcycle-rivaling, Lotus-bothering 463 pounds, and Moon gravity meant it was lighter still unpacked, tipping the scales at 75 pounds. Apollo 15, 16, and 17 had LRVs, nicknamed “moon buggies” to evoke the dune buggies of the early ’60s.

Crucially, it meant astronauts could travel further without walking and carry more samples back to the lunar lander. Although they stayed within walking distance in case of failure, range was also respectable for the time: 57 miles from a pack of non-rechargable batteries packed with silver-zinc and potassium hydroxide.

All three LRVs used by subsequent Apollo missions remain on the Moon, their batteries long since flat. Pioneers of their time, EVs have increased in popularity somewhat since their deployment of their Moon-going brethren.

Sinclair C5 (1985)

OK, so perhaps the C5 is stretching the definition of “car”—even its instigator, Sir Clive Sinclair, described it simply as a “vehicle”—but it had a Lotus-designed “spine” chassis and was a bold attempt at bridging the gap between car and bicycle.

Inventor Sir Clive, best known for his ZX80, ZX81, Spectrum and QL range of home computers, had long been interested in electric vehicles, and he bravely, if rashly, assumed that cyclists and cash-strapped car buyers would be, too.

A recumbent tricycle, the C5 was built in partnership with Hoover in Wales (take that, James Dyson), but its sulfur battery performance and weather protection left much to be desired; many of the parts needed to keep riders clean and dry were sold as optional extras.

Sales were nowhere near Sinclair Vehicles’ lofty projections. Unfairly maligned by history, the C5 has since found itself a vocal and active fanbase, with many users upgrading their C5s to improve the relative lack of pace and range.

Sinclair never gave up on the electric vehicle concept, either: His battery-powered Zike bicycle was a moderate success in the ’90s, but larger C10 and C15 models never made it into production.

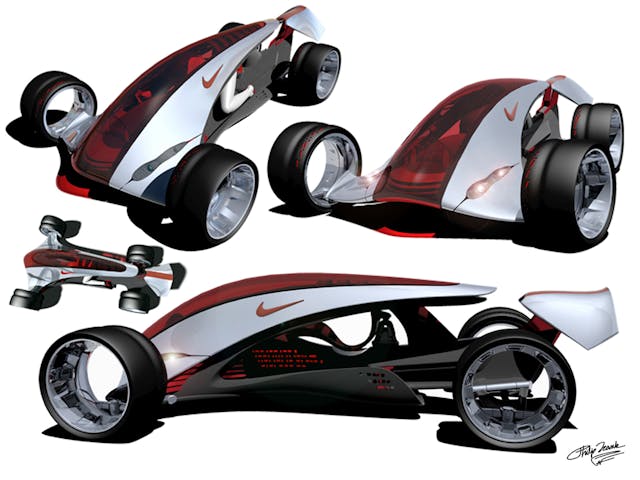

Nike One 2022 (2004)

A glimpse into the future, commissioned by game developer Polyphony Digital for Gran Turismo 4, no cars look like the Nike One 2022 yet (at least, not that we’re aware of).

Yes, Nike built a car, at least virtually; while scuffed Airs remain an excellent shoe for heel-and-toeing, the One took that idea to its logical conclusion. Interestingly (or terrifyingly), the One had no fuel tank – as in The Matrix, the driver was the fuel source, driving the One in a motorcycle-style position and using a special suit to power the four hub motors of the One via nanotechnology.

The collaboration came about after a chance meeting with Gran Turismo creator Kazunori Yamauchi at Nike headquarters. Industrial designer Phil Frank, best known in the automotive world for his work on the Saleen S7, was tasked with shaping the new car, which existed in the confines of the game only.

It could be driven and selected once the player had won it through successful completion of their International B racing license or, fittingly an all Saleen S7 race known as the Saleen S7 Club. And it was light on its feet, offering 260 hp and a 160 mph top speed.

More recently, Frank penned a Nike One “Launch Edition” to commemorate the original Gran Turismo design, with rumors afoot the One will appear once again in an update of Gran Turismo 7.

Ford 021C (1999)

It’s not uncommon for designers of cars to help shape other products of industry. Witness Giugiaro’s family of watches for Aliens (including the “Ripley” 7A28-7000) or Pininfarina’s range of drink machines that you’ve likely used to create some unholy mixture of sodas at a Five Guys.

Rarely do said design firms go back the other way and design a car, but Ford liked the portfolio of renowned industrial stylist Marc Newson so much that it commissioned him to create a concept car for the turn of the century.

Displayed at the 1999 Tokyo Motor Show, where it won a “Best Concept Car” award, the 021C, named for the new millennium (and dictating its paint color on the Pantone scale), was a simple three-box shape with more than a passing resemblance in profile to the 1963 Falcon, though the 021C’s footprint was smaller than that of the contemporary Ka.

Built by Ghia, the 021C embodied many cues that those familiar with Newson’s furniture might recognize. The boot, for example, pulled out like a drawer. Newson used plenty of aluminum and rubber, while all extraneous features were removed or simplified, apart from a period Blaupunkt head unit that dropped down from the dashboard.

Though no powertrain or architecture was specified, Newson wanted front-wheel-drive to allow for a flat floor, and pillarless suicide doors, with ’60s-style swivel seats to make it easier to get in and out.

Bayer-BMW K67 (1967)

Polyurethane is a familiar material for those wanting to uprate their suspension bushings, but back in the late ’60s it was thought that it might do for the manufacture of entire car bodies, as a means of beating corrosion.

The shape of the Bayer-BMW K67 was the work of Hans Gugelot’s design bureau, in a joint venture with Covestro, a subsidiary of chemical giant Bayer, which provided the raw materials.

Five cars were built using 2.0-liter BMW M10 engines to 2000 Ti specifications, but while the results were favorable, and the two-piece body relatively light at under 2000 pounds, it struggled to find takers. Industrial relations between the steel mills and car makers were hard-won and hard-fought—and the investment needed to bring polyurethane body production to the mass market proved too expensive.

Gugelot did bring something else to the party with the K67’s styling, however: the now-common feature of indicators integrated into the wing mirrors, which wouldn’t appear again until Keith Taylor’s 1989 patent with Chrysler Corporation.

Polyurethane’s automotive career wasn’t, however—apart from suspension parts, it continues to be used to this day in sound deadening and body kit applications.

Jiotto Caspita (1989)

Underwear isn’t the first thing you’d associate with motoring—no matter how many times Jeremy Clarkson used to mention it on Top Gear when describing the effects of the Ford Probe’s styling.

Nevertheless, Japanese lingerie brand Wacoal—specifically its president, Yoshikata Tsukamoto—wanted an F1 car for the road, in a manner not dissimilar to the Yamaha OX99-11, another F1-inspired machine that never made it. Jiotto Incorporated was the result: a joint venture between Wacoal and Dome Engineering Company (better known for its wild Zero and P2 sports cars), the Caspita was to be a gull-winged, carbon-fiber-chassis supercar.

Both Mk1 and Mk2 variants used detuned F1 engines, the former a 3.5-liter, Motori Moderni flat-12 designed for Subaru’s unsuccessful 1235 F1 car. It was as unsuitable for the Caspita as it was on the track, though it did live on, as the design rights were later bought by Koenigsegg, whose first chassis was designed around the unit.

Later attempts to update the car with a 3.5-liter Judd V10 also fell flat, as the 30 orders placed at the height of Japan’s “bubble economy” melted away in the market crash that defined the early ’90s.

Vespa 400 (1957–1961)

Making the leap from scooters to cars was a logical progression for the upwardly mobile manufacturer. The likes of Allard, Bond, Peel, et al offered scooter-based cars as a means of basic transport, not to mention the likes of Daihatsu, Fuji, and Suzuki looking to improve their station after World War II.

For Piaggio, makers of the famous Vespa, a small car made plenty of sense, especially in the crowded Italian streets full of families desperate to keep mobile.

Were it not for the Fiat 500, Piaggio’s car might have stood a chance. Launched in 1959 by a trio of successful racing drivers—Jean Manuel Fangio (!), Jean Behra and Louis Chiron—the Italian-designed, French-built 400 was a tiny 2+2 family saloon priced to undercut Citroën’s 2CV. Nevertheless, competition was fierce, with the likes of the Goggomobil T250 and Autobianchi Bianchina vying for space in a crowded market.

Poor fuel consumption, a bad gear change, and a complete lack of refinement did much to dent sales; by the time these problems were fixed, the damage had been done. Fiat’s Giovanni Agnelli was the 400’s most outspoken critic and is said to have threatened Piaggio with a Fiat-built Vespa rival if sales of the 400 continued.

Okamura Mikasa (1957–1960)

True entrepreneurs will always find success, and so it proved with Yoshiwara Kenjiro, founder of Okamura. Known nowadays for its furniture, it survived World War II by producing anything that could be made in its engineering works. Pots, pans, kettles, and garden furniture all helped keep the lights on.

After a chance encounter with a broken scooter, Okamura explored the idea of making two-wheelers, especially as postwar restrictions on Japanese industry curtailed a venture into aircraft. It was how the scooter got its drive, however, that inspired Okamura’s engineers, prompting intensive research into an automatic gearbox that would easily propel a range of cars.

Instead of building scooters in the interim, Okamura decided to hunt for buyers of domestic cars, a commodity sorely needed in Japan. Heavily inspired by the Citroën 2CV, the Mikasa range was born.

Fitted with its AK-4 automatic, and a 585cc four-stroke twin of Okamura’s own design, the company built around 500 units in total. Okamura simply didn’t have the money to develop the Mikasa range further, though production of its torque-convertor automatic prospered via government contracts.

Falling back on its previous office furniture and fixtures contact, the firm survived, and continues to prosper to the present day; a surviving Mikasa Tourer remains on display at its Tokyo museum, which opened in 2009.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark us.