Media | Articles

3 ways I squeezed more power from my race bike

In the endless pursuit of more speed aboard my 1986 Honda XR250R motard, it has now come down to searching for incremental gains in power. The aerodynamics are terrible, the suspension is pretty good, and the brakes are great. So that leaves horsepower as the low-hanging fruit. But to be clear, there is no truly low-hanging fruit here.

Regular readers will recall I converted this bike from an air-cooled thumper designed for trail riding and toodling around the farm into a dedicated road-racing machine. Sure, it’s an odd choice, but with lots of ground clearance and suspension travel, the XR250R is a forgiving and fun bike to ride. It’s just important to remember such use is far outside the engineering parameters of its early 1980s origins. The lack of horsepower means corner speed is the only way to decent lap times, and that requires real understanding of proper riding technique, which scales up to larger bikes that might one day be in my future.

After running three weekends with this bike last year, I realized that while chasing additional power would likely be a fool’s errand, there were some easy ways to eke out a little extra. Since bolt-on solutions do not exist for my “problems,” and I had to engineer my own performance package, I looked no further than the basics.

More air (and exhaust)

There’s an old saying that engines are nothing more than air pumps. More air in and more air out makes for higher power potential.

To get more air out, my first step was to grind down the welds inside the factory exhaust. This opened up nearly a quarter-inch of additional diameter, which is quite significant when talking about airflow. With a couple more paychecks saved up, I made the jump up to an even larger stainless-steel header pipe. Plenty of air leaving.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

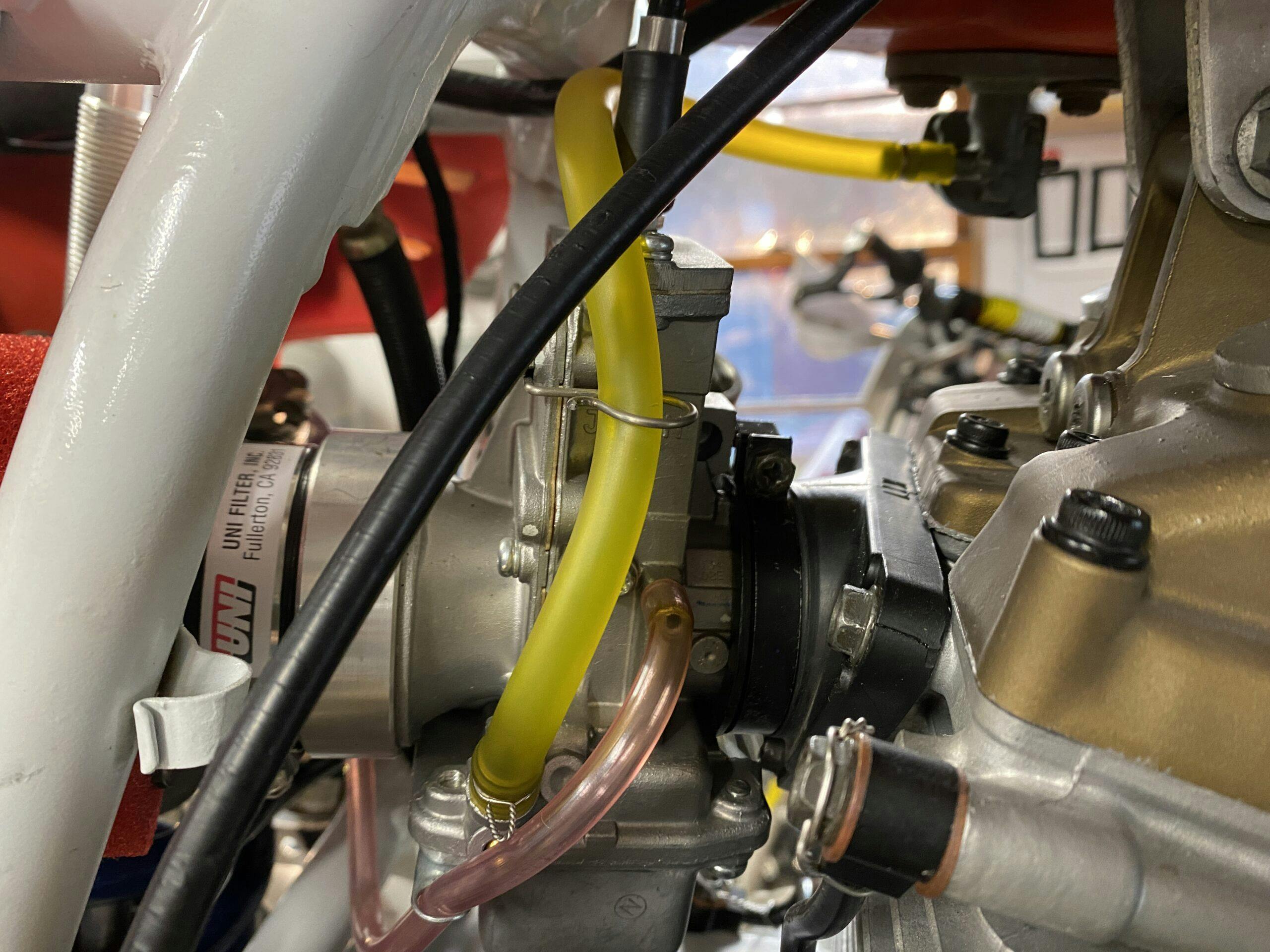

Sadly, there still wasn’t much going in. Despite my DIY porting of the cylinder head and adding a larger, 34-mm Mikuni carburetor, the whole operation was drawing through the drinking straw that is the factory air box. This meant all air had to travel through a rubber tube that changes shape and volume as it passes around the rear shock.

After finding a mangled airbox from a bike I parted out a while back, I had the idea to swap to a free-flowing pod filter. The guts of the old airbox would act perfectly as a deflector to protect the shock from debris flying off the rear tire, and I could keep open the left side, which has the number-plate mounting points. Because I put the pod filter right on the carb, the bike still has all the proper mounting points for the things it needs. Crucially, it also has a lot more airflow.

More fuel

Most motorcycles like this XR have simple fuel systems. Fuel tank, petcock shutoff valve, hose, carburetor. Having already changed the carb to a larger model, the only thing left here was the fuel hose, which in this application is actually something of a fuel pump. The stock XR250R is made for grunting around at low rpm and has a fairly large fuel bowl, meaning there is little risk of pulling fuel up through the main jet faster than it can refill from the tank.

In prepping the bike for racing, however, it only took a couple full-throttle pulls down the street to see I had fuel delivery problems. The amount of air being drawn into the engine corresponds to the amount of fuel being consumed, since we tune the engine to run on a particular fuel-air ratio.

With a significantly larger fuel hose, I essentially created a larger fuel bowl. The inlet into the carb is still a slight restriction but not nearly as tight as the petcock. No more fuel issues.

More compression

More air and more fuel are the basics of making more power from an engine. Increasing compression is a little more involved. This is the ratio between the volume of the cylinder with the piston at bottom dead center and the volume when the piston is at top dead center. The tighter you can squeeze the air and fuel mixture before lighting the spark plug and allowing the burning mixture to expand, the more energy can be converted from the potential in the fuel to the kinetic energy of piston movement.

To solve this, I changed the piston for one with a slight dome and also had the cylinder head decked to remove a couple thousandths of an inch. Think of this as lowering the ceiling in a room. The volume of the space changes, especially when the piston is at the top of its stroke. More squeeze, more power.

The change demands that I be careful about what fuel to run, as lower-octane fuel is more susceptible to igniting by itself when compressed. Factor in the added work of ensuring that valve-to-piston clearance is acceptable, and this step borders on “not easy.” The effort is worth the reward, though.

***

The key to getting more power from your engine is to understand how it makes power—and what adjusting the factors of that equation can do. Sure, for most engines you can copy someone else’s parts list and assemble a similar mill that you know will work. But where’s the fun in simply being a credit-card mechanic?

Individuality requires knowledge. Everything you learn on one project can be used on future projects, and before you know it, you’ve spiraled up to building really interesting stuff. Start with the basics, and you never know where you’ll end up. That sounds a lot more fun than just ordering parts, right?

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

When I was doing a lot of track days on my CBR 600RR, I did little to the engine, other than a full race exhaust and Power Commander. I focused on removing weight, and was able to cut 30 lbs. One of the tricks I learned that you may have already tried was a 520 chain conversion. The CBR came with a 525, so just a conversion alone saves a little bit. But going with lighter sprockets and higher-quality chain helps the motor spool up a little quicker, as well.

Good call. This bike is factory 520 chain, but I have been hunting for aluminum sprockets in the unusually small size I run on this bike. Factory gearing is 13/48 and I run 13/42 on smaller tracks, bigger tracks is 14/42. Would love to find an aluminum 40 and 44 to give me some additional adjustability.

I believe Sprocket Specialists makes them to order. Been a while since I’ve bought one

Good deal! I’ll have to reach out.

The last two paragraphs say it all – and can apply to life as well.

I would recommend that you contact Brian Crower about re-profiling your cam(s) to take maximum advantage of what you have done so far, and be prepared for a noticeable power increase. The cam is the heart of your engine and improving the valve timing and lift will yield the largest gain, aside from artificial aspiration.

Megacycle can likely help you out with a cam. That said, pre-’96 XR250s are notorious for running hot. I’d add an oil cooler. And if that belly pan isn’t full of holes for air to pass through, drill some!

Drilling the belly pan would be counterintuitive. It is only there as per the rulebook that requires it can hold all the oil from the crankcase in the event the connecting rod decides to remodel and add a window.

This bike still has the factory oil cooler but I am sketching up ideas for a larger aftermarket oil cooler. Would love to do a Megacycle cam, but the $$$ just doesn’t make sense yet.

Just wanted to mention that 009 is the spy that went in before James Bond and was killed in just about every Bond movie. Just saying. Be careful out there.

That’s true but it never really bothered me. Personally I don’t think superstitions have a place in racing. Sadly a rulebook change has made that number unacceptable so I’ll have to find a new one if I find my way to the track with AHRMA this year.

I’d take off the front fender which was only meant for riding in the dirt. It’s like a sail mounted up there and probably also negatively affects cooling at high speed.

I should, but am too vain to deal with the even goofier look without a fender. Maybe I’ll get over myself and put performance over appearance this season. Front fenders are not required for my class per the rulebook, so I have nothing to lose.

When I was only 14 or 15, I bought a moped and after a few months of wizzing around at a governed 25 MPH, I wanted more speed. I researched the model Puch moped for the Euro market version that (hopefully) wasn’t restricted to 1.5 HP and 25 MPH. I discovered through my selling dealer that they had larger jets listed in the parts catalog. I ordered the much larger (equals more fuel) jets for the carburetor. Then I got my Dremal moto-tool and cleaned up the welds on the exhaust port flange and cylinder head. Basically, I opened up the “hole” and gasket-matched the port. Then I saw the intake had a restricted gasket (NASCAR restrictor plate?) and port-matched the round carburetor throat to the oval cylinder head intake port and made it a gradual transition and therefore much more free flowing. Lastly, I removed the exhaust baffle & with some experimentation, cut out every other baffle plate. When I was finished, it would now go 50 MPH on flat, level ground. Needless to say, I was breaking neighborhood speed limits on a daily basis. I even got pulled over on radar doing 47 in a 25 zone. I told the officer “impossible!” this is just a moped, knowing full well all my modifications were not readily visible and really, who in their right mind would modify a moped!?!

In Ohio they are limited to 1 hp and 20 mph. My son garbage picked a very nice condition J.C. Penny Swinger II (1979 mfg date) moped a couple of years ago. A couple of hours to clean up the fuel system and carb and that thing runs like a Swiss (actually Austrian) watch. From what I have read, it’s pretty easy to bump it up to 2 hp and 30 – 35 mph. Maybe when I have some spare time.

With a stock camshaft, I found that the XR 4 strokes responded well to retarding the cam timing (~3° with 1 tooth shift in timing gear). This moves the peak power up in the rpm range a little where you need it.

Take Kyles advice and check valve clearance when you mess with cam timing !!!’