Media | Articles

13 British cars that were floored by flaws

I love British cars, I really do, and that’s despite over the years sometimes joining in (said ruefully, now) with the good-natured teasing of such motoring flops as the Austin Allegro and Reliant Robin. To all British car fans I’ve wound up, I humbly atone.

However, British cars have occasionally suffered from curious national characteristics, which sealed in actual flaws that have since become their undoing.

The first part of this you can lay fair and square at the U.K. Treasury’s door. In 1910 it asked the RAC (Royal Automobile Club) for a way to tax cars on a sliding scale, and what came out of that was a system based on cylinder dimensions—total cylinder surface area. To build cars that were cheap for owners to tax, British manufacturers therefore opted for a narrow bore and a long stroke in small-capacity engines. This stopped the Ford Model T from dominating the industry, but sometimes made Britain’s own popular models gutless and prone to premature wear.

Besides the fiscal structure, British carmakers were frequently underfinanced, leading to cut-price thinking, and because there was a huge captive market, called The British Empire, they could also be lazy about rigorous development; British cars from the 1930s to the 1950s were honed for puttering around British suburbs so prototypes didn’t need to visit the Arctic Circle or Death Valley.

The 13 cars below, therefore, suffer from some of these legacies, and sometimes also a failure to fit into a suddenly changed future. None are terrible, but all their flaws were probably avoidable.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Singer Nine Le Mans Replica, 1935

Singers were some of the most popular small cars of the early 1930s and the Coventry company was keen to buff up its image by taking on MG and Riley in motorsport. That’s why it took four specially-built sports versions of its best-selling 9hp model to Ards in Northern Ireland in 1935, to have a crack at the Tourist Trophy race. It just could not have gone any worse: three of them crashed at the exact same spot at the tight Bradshaw’s Brae corner because of a design fault in the cars’ steering linkage—a fault that had not shown up on the sweeping corners at Le Mans. The drivers, thankfully, stepped uninjured from the mass wreckage, but the reputational effect on sales was catastrophic as punters worried it might happen to them too.

Morris Minor MM, 1948

The first true masterpiece from the agile mind of Alec Issigonis should have come with an all-new flat-four “boxer” engine with eager performance to match its excellent roadholding, ride comfort, and balance. However, just as it was shaping up to be a global pacemaker, the accountants intervened and the engine was axed. In its place went a 918cc sidevalve motor wheezing its way from the 1930s, and the Minor was rendered so underpowered it could barely manage the steep hills of San Francisco. And that was a huge shame, because the Volkswagen Beetle had no such issues and by 1955 had crushed the Minor’s U.S. export prospects, selling 31,000 where the hobbled British competitor shifted just 700.

Land Rover Series I Station Wagon, 1949

The Range Rover is the first upmarket SUV, right? Wrong. Land Rover was in the very same territory in 1948 with this one. It really was a marriage of rut-rider and luxury, since the passenger compartment was fully coachbuilt by Tickford in Newport Pagnell—its craftsmen soon after became part of Aston Martin—and complete with leather upholstery and even a tinplate cover over the spare wheel to make it look less truck-like. The problem, though, was the price. Unlike the standard Land Rover, which was a commercial vehicle, this one came with punishing levels of Car Tax that just made it too expensive for most people. Only 50 were sold in the U.K. When Land Rover had another go at station wagons in 1954 it got the rivet guns out and made them from sheet aluminum; super-basic but much more affordable.

Daimler DK400, 1954

This is the shameful car that lost Daimler its place in Royal circles. The marque was the Windsors’ favorite going right back to the dawn of motoring but in 1953 the company decided to axe its imposing straight-eight models and replace them with the DK400. This was merely an elongated version of the Daimler Regency, with its rear track extended so comfortable three-abreast seating was possible. Matters came to a head when Daimler delivered two DK400s to the Royal Mews after many months of delays, most of them caused by the DK400’s feeble performance as it struggled to haul around a couple of tons of mobile throne room. Even then, they were severely underwhelming cars, and the Royal warrant was not renewed. With Princess Elizabeth an owner since 1950 and the Duke of Edinburgh also a fan of the marque, Rolls-Royce would instead supply the official state car in the decades that followed.

Vauxhall Victor F-type, 1957

Vauxhall’s mighty General Motors overlords in Detroit decided to shake up its sleepy British outpost in the 1950s. Its aim was to create a new compact sedan that it might also be able to sell across the U.S. and Canada, as demand for compact models was soaring. To do this, they insisted on the trendy design theme of the 1955 Chevrolet Bel Air as a starting point.

This decision came with a tight schedule to get the car into production in 1957. Production engineers in Luton were overwhelmed with the task; the rush almost killed them. So while there was nothing greatly amiss with the 1.5-liter four-cylinder engine, the flashy body had issues aplenty, which resulted in it becoming one of the most notoriously rust-prone British cars ever. Water trickled in through the seals around the fancy, wraparound front and rear screens, and flimsiness in the monocoque structure meant doors and bonnets were ill-fitting, letting in even more rain, spray and mud. There were also nasty vibrations at around 50 mph. Its brief status as “Britain’s most exported car” came to an abrupt end when Pontiac and Oldsmobile dealers refused to take any more. The few that survive today, mind you, do look pretty cool.

Jaguar 3.4-liter “Mk 1”, 1957

It’s not always appreciated that Jaguar pioneered the compact sports saloon in 1955 with its sleek and modern 2.4-liter. It was also the company’s first unit-construction model, and the engineers left nothing to chance in making sure the chassis-less structure wouldn’t twist or buckle. Trouble was, it was so robust that the car’s performance was somewhat sluggish. The solution was to drop in a 3.4-liter engine not a million miles away from that in the Le Mans-winning D-Type. This utterly transformed the car and not always for the best: acceleration and top speed were now utterly thrilling but the drum brakes and suspension set-up of the time simply could not cope. This could be a lethal car on wet roads even in experienced hands; F1 world champion Mike Hawthorn died after crashing his. Disc brakes, and then an overhaul to Mk 2 status solved things.

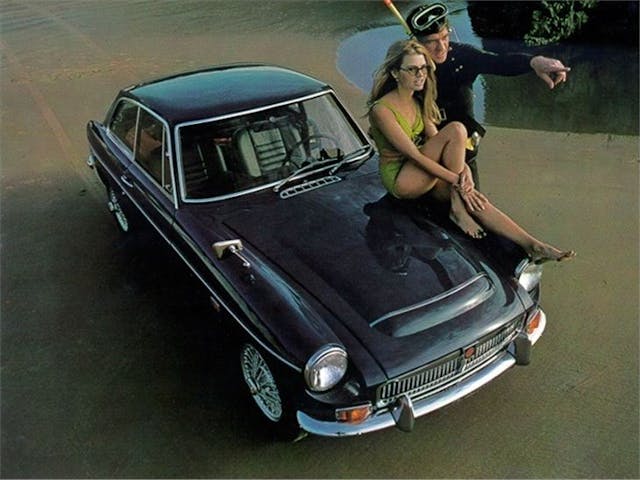

MGC, 1967

A misguided attempt to both replace the Austin-Healey 3000 and act as an MGB-based range-topper for the MG line-up, the MGC was hamstrung from the start for want of a decent motor. BMC installed the 2.9-liter straight-six from the Austin 3.0-liter, which couldn’t even be shoehorned in—they had to redesign the engine bay, create a new torsion-bar suspension system, and bulge the bonnet in two places to make space. After all that, the engine upset the sweet handling of the MGB, resulting in untidy understeer in corners. It was set up as a relaxed cruiser with bigger wheels, so wasn’t all bad—Prince Charles liked his—but it didn’t exactly worry Alfa Romeo. The all-iron engine weighed 209 lb (95 kg) more than the standard B’s four-cylinder power unit … yet when they later installed a Rover V-8 engine in the car, not only did it fit like a dream but it weighed 40 lb (18 kg) less than the B’s B-series four.

Morris Marina, 1971

In truth, the often-maligned Marina was broadly okay, but it was designed both in a hurry and on a slender budget. Here was a mishmash of all that British Leyland could throw together in great haste to provide something a bit like the market-leading Ford Escort and Cortina. Biggest corner-cut of all was the torsion bar front suspension from the Morris Minor—the car it was meant to replace—which made it understeer and bounce around on rough roads. This was soon fixed with some tweaks and the Marina’s biggest flaw then became simply its overall mediocrity. The public, though, didn’t seem overly bothered and BL sold over a million of them, providing reasonable service for most owners. Intended as a stopgap with a five-year life, the platform finally bowed out, as the Morris Ital, in 1984.

Jensen-Healey, 1972

After BMC had failed to replace the much-loved “Big” Austin-Healey now it was the legendary Donald Healey’s turn to have a crack, and with this car—built by Jensen and bankrolled by San Francisco car importer Kjell Qvale—they made an excellent attempt. Opinions differ on how well it drove, as Healey aimed for a tradeoff between handling and ride comfort, but the roadster’s Achilles’ wheel could be found under its bonnet.

For reasons of both glamour and performance, Healey agreed to Lotus’s offer of its twin-cam, four-cylinder engine. He should really have gone for something less exotic because it was too temperamental for a mass-made car, suffering oil leaks and sometimes refusing to start. Once dealers had sorted out that lot they then had to tackle the next complaint from irate owners—rapidly-spreading rust. It was all too much for a small car company to cope with, and Jensen went bust in 1976; the Healey partly to blame.

Jaguar XJC, 1974

The faster you drove the beautiful, two-door version of the XJ6 or XJ12, the louder the annoying whistling sound would become, just above the right-hand lens of your Reactolite Rapide sunglasses. Jaguar struggled to achieve air-tight sealing between the frameless side glass and the pillarless apertures which made the car so gorgeous when all the windows were lowered. The XJC is often stated as a personal favorite of company founder Sir William Lyons, yet making this version, painstakingly cut-and-shut from standard production saloons, was a tricky business; a vinyl roof was required to cover up the stitches from surgery. After just three years the car was dropped as simply more trouble than it was worth.

Jaguar XJ-S, 1975

A rather brilliant car, this. It might have been detested by E-Type fanatics but this impressive GT was intended to ambush the Lamborghini Espada and Ferrari 365 GT/4, not replace the famous two-seater. Its flaw was external: the economy. This 18-mpg V-12 aerodynamic slingshot went on sale just as the worst fuel crisis in living memory bit hard, with inflation soaring just like the XJS’s rev-counter needle. On top of that, Jaguar’s owner British Leyland had just been outed as insolvent and subject to an emergency nationalization. There were more pressing things to fret over than the fate of this plaything of the rich.

Reliant Scimitar GTE, 1976

Reliant reckoned it had thought of everything with the second-generation GTE. Longer, wider, roomier, lots more crushed velour inside, but still with those winning looks, excellent versatility and ample, dependable urge from the 3-liter Ford V-6 fresh from the top-dog Capris and Granada. In a small car factory, though, things can get overlooked, and in this case someone didn’t pay enough attention to the way the fuel line fed into the V-6’s carburetors. It would sometimes detach itself, spraying petrol over the hot exhaust manifold. An engine bay fire was then possible, and this plastic-bodied car could turn into a real tinderbox.

Rover CityRover, 2003

Desperate times called for desperate measures, and when BMW offloaded what was left of Rover to its management in 2003, the business came without any development facilities, just the Longbridge factory and sundry old cars to make in it. The Indian-built Tata Indica represented a chance to get a new Metro-sized car into Rover showrooms at almost no cost, and that’s what happened. Just a few alterations to the badges, suspension settings, and gearbox were deemed necessary. As basic transport the so-called CityRover was just about bearable, but Rover decided to sell the seven-grand supermini at a hefty premium above the fantastic new Fiat Panda. The company didn’t have the money to either advertise or improve the car, and less than two years later the CityRover went down with the rest of MG Rover.