Media | Articles

On the Bayou, a reckoning comes for a car collection and a peacemaker

Linda Rhodes is a storyteller, a fighter, and a Bayou Peacemaker. That last one is her nickname, given because she seeks peace between external forces and the communities situated in and around Pineville, Louisiana. Pineville is known for its small college and a Louisiana National Guard installation, and Linda works tirelessly to honor those in underrepresented communities in both Pineville and the larger, adjacent city of Alexandria. She honors the sacrifices of those who served in our armed forces with American flags on Memorial Day and ensures the legacy of the Buffalo Soldier in Central Louisiana is not forgotten in our modern times.

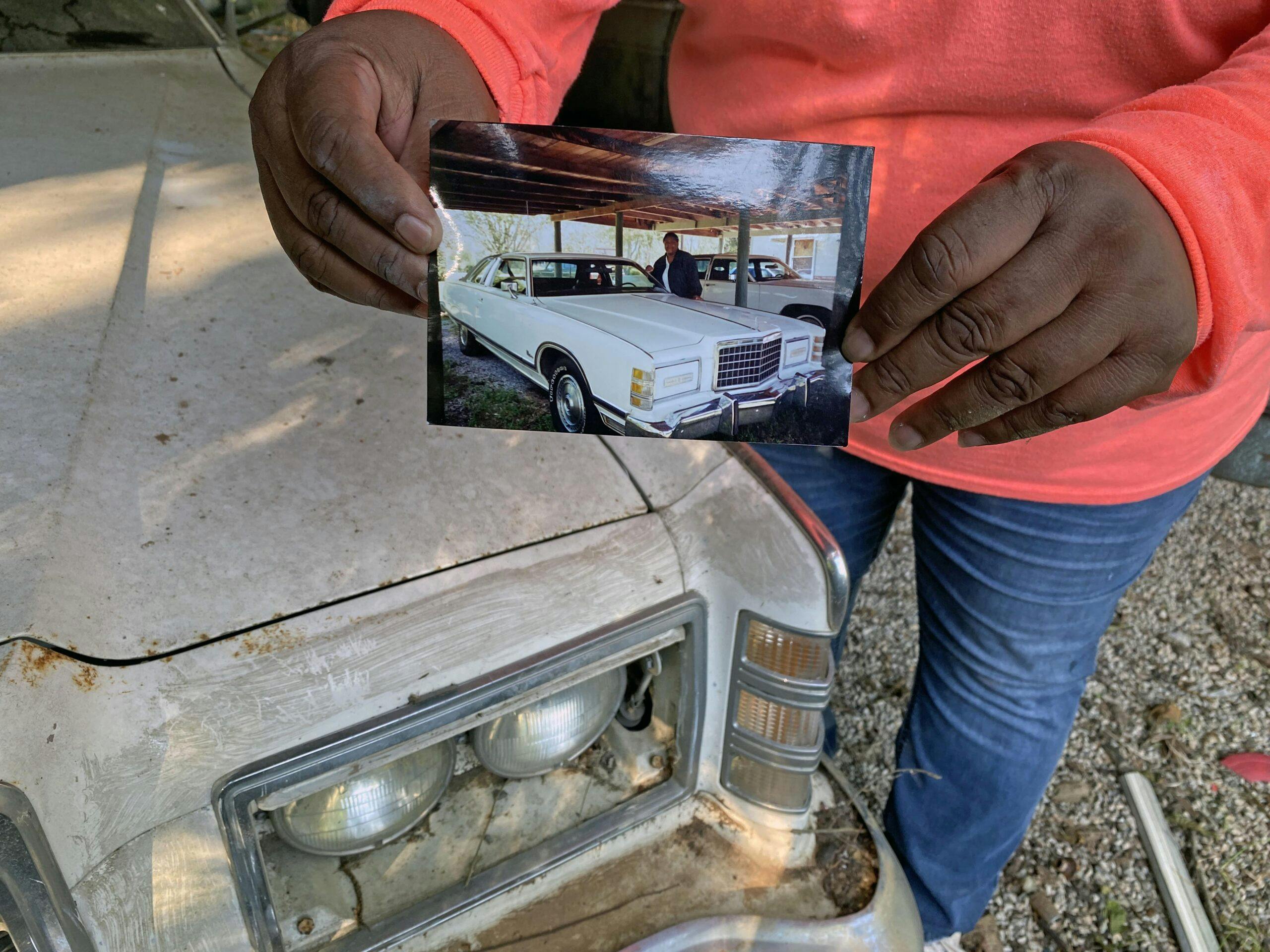

These days, however, Linda has a new mission: to find new homes for the enviable portfolio of property, cars, trucks, collectibles, and clothing her father, Carter Rhodes, amassed during his lifetime. Carter died in April 2022 at the age of 81. His estate includes approximately 100 antique cars and trucks.

Linda laments the fact that her father didn’t sell off these vehicles once they were forced outdoors. Now, they’re her burden to sort out. She reached us via email this past spring, asking for help finding appraisals so she can sell the remaining 75-or-so cars. Whatever funds were available for such services she spent cleaning up her father’s land. I answered the call, asking for two things in return: the chance to share her family’s story, and a bit of kickin’ cajun food.

She disappointed on neither count.

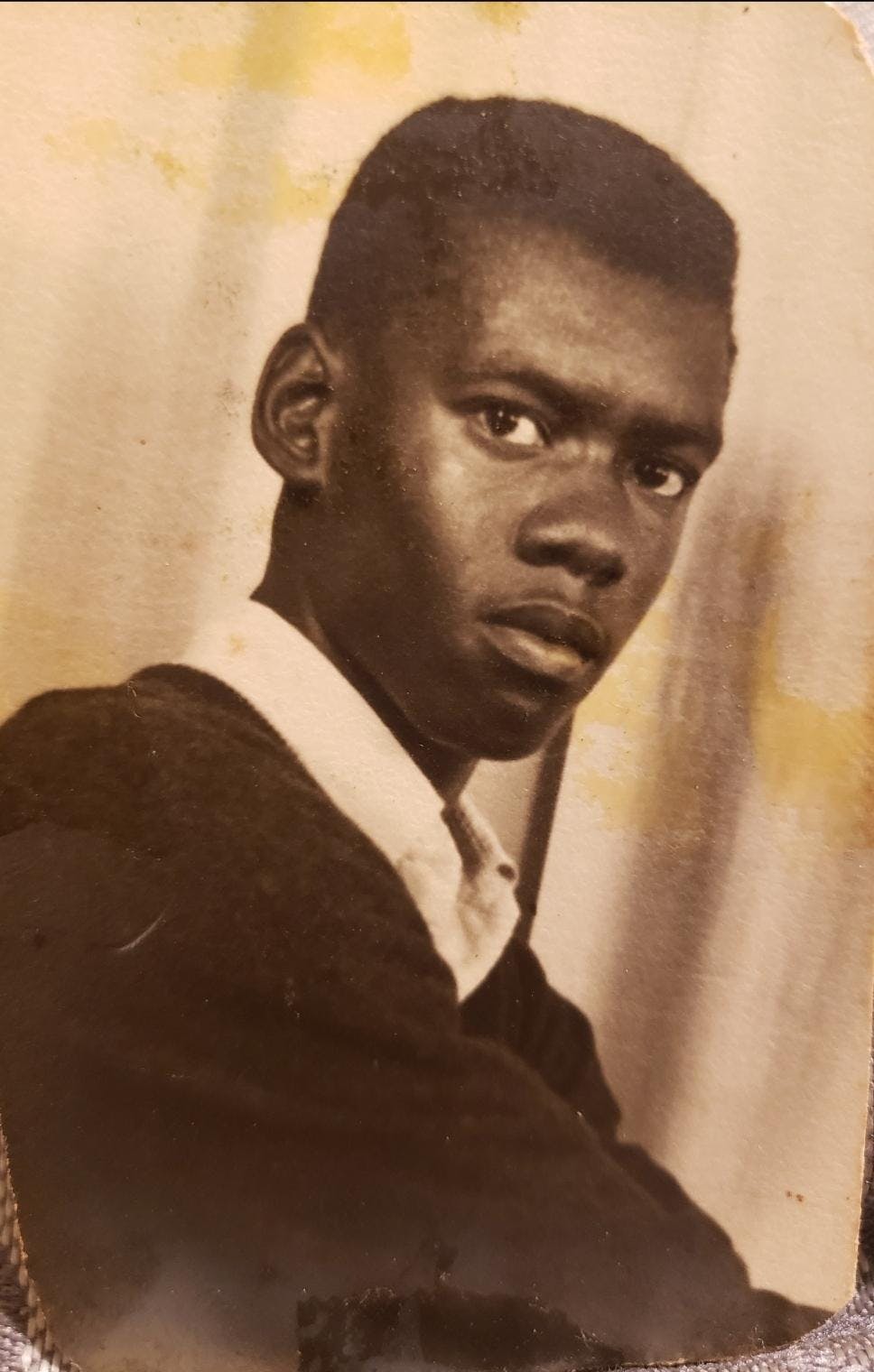

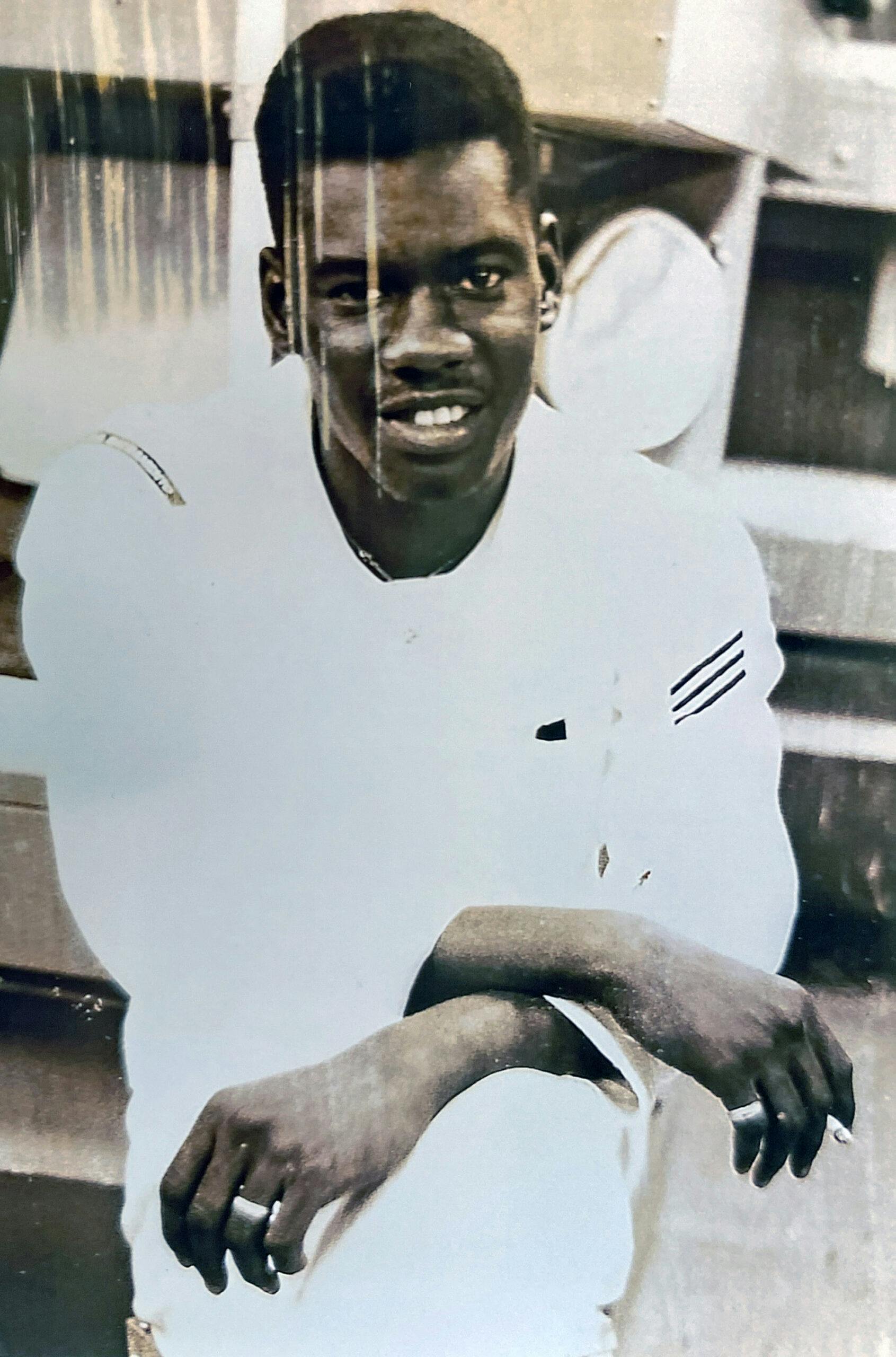

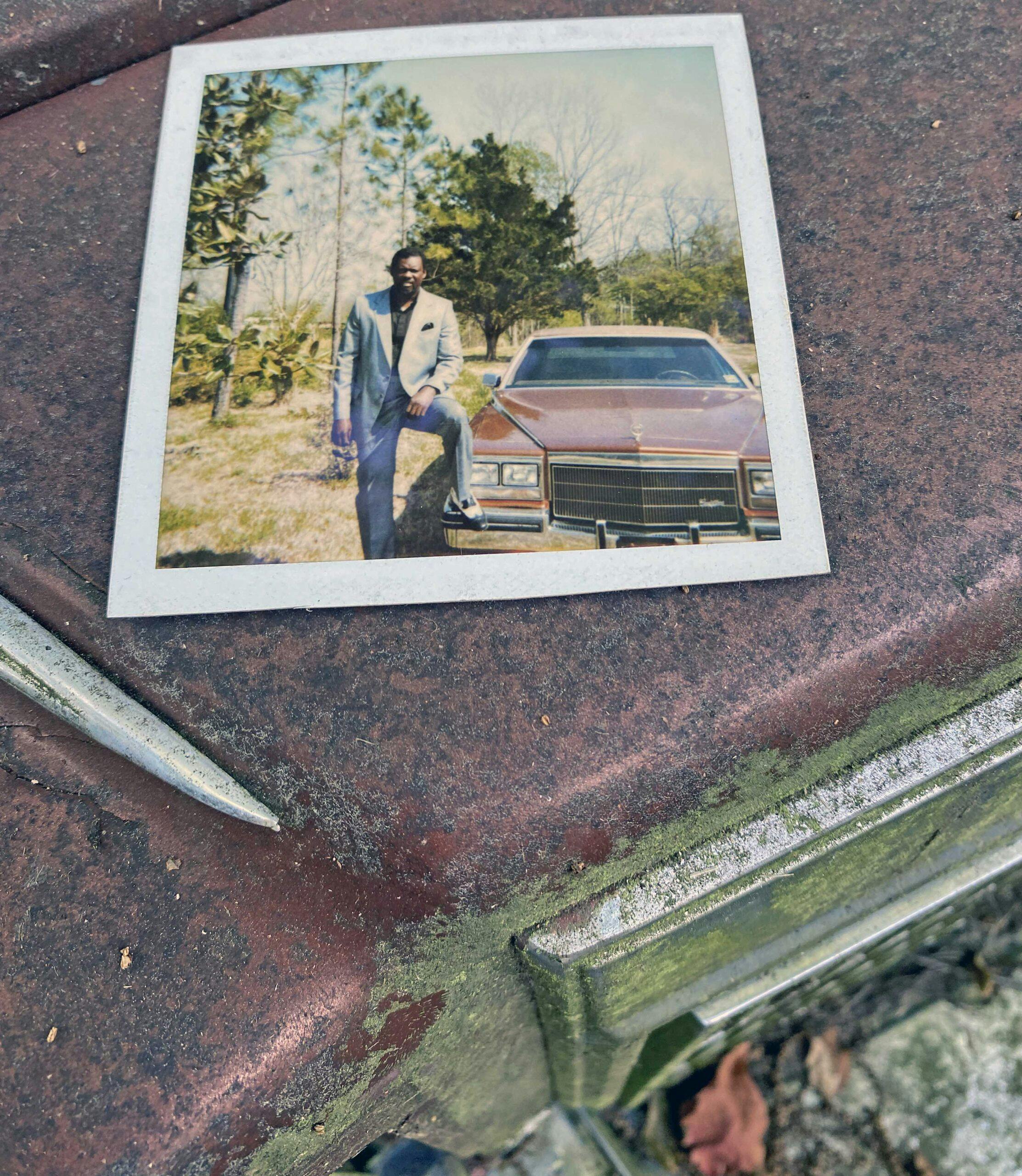

Carter’s love of cars went back to his childhood. He used the proceeds of his after-school job (picking cotton from Louisiana’s fertile fields) to purchase fast machines. Over time, Carter’s need for speed was matched by a taste for luxury.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

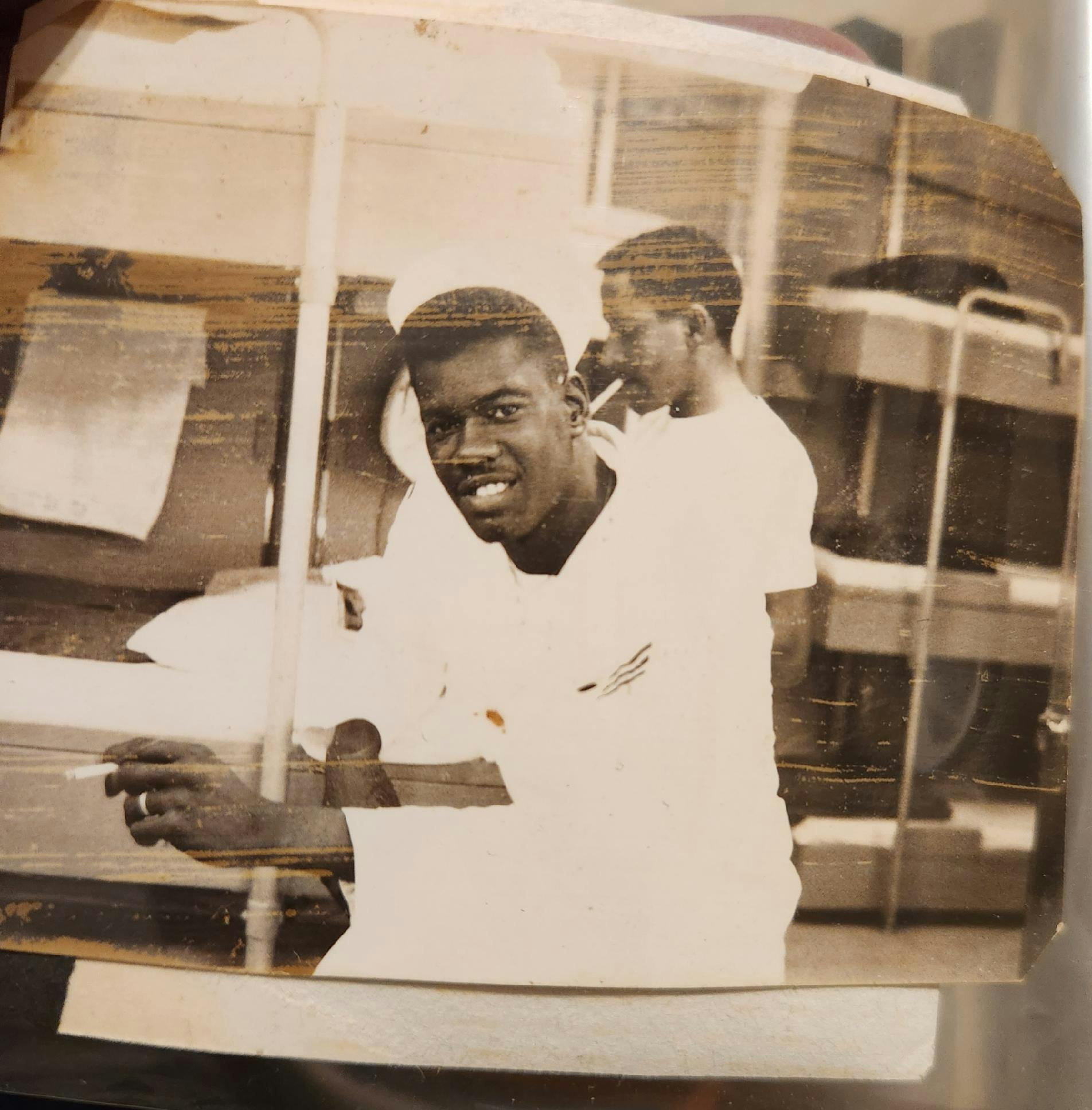

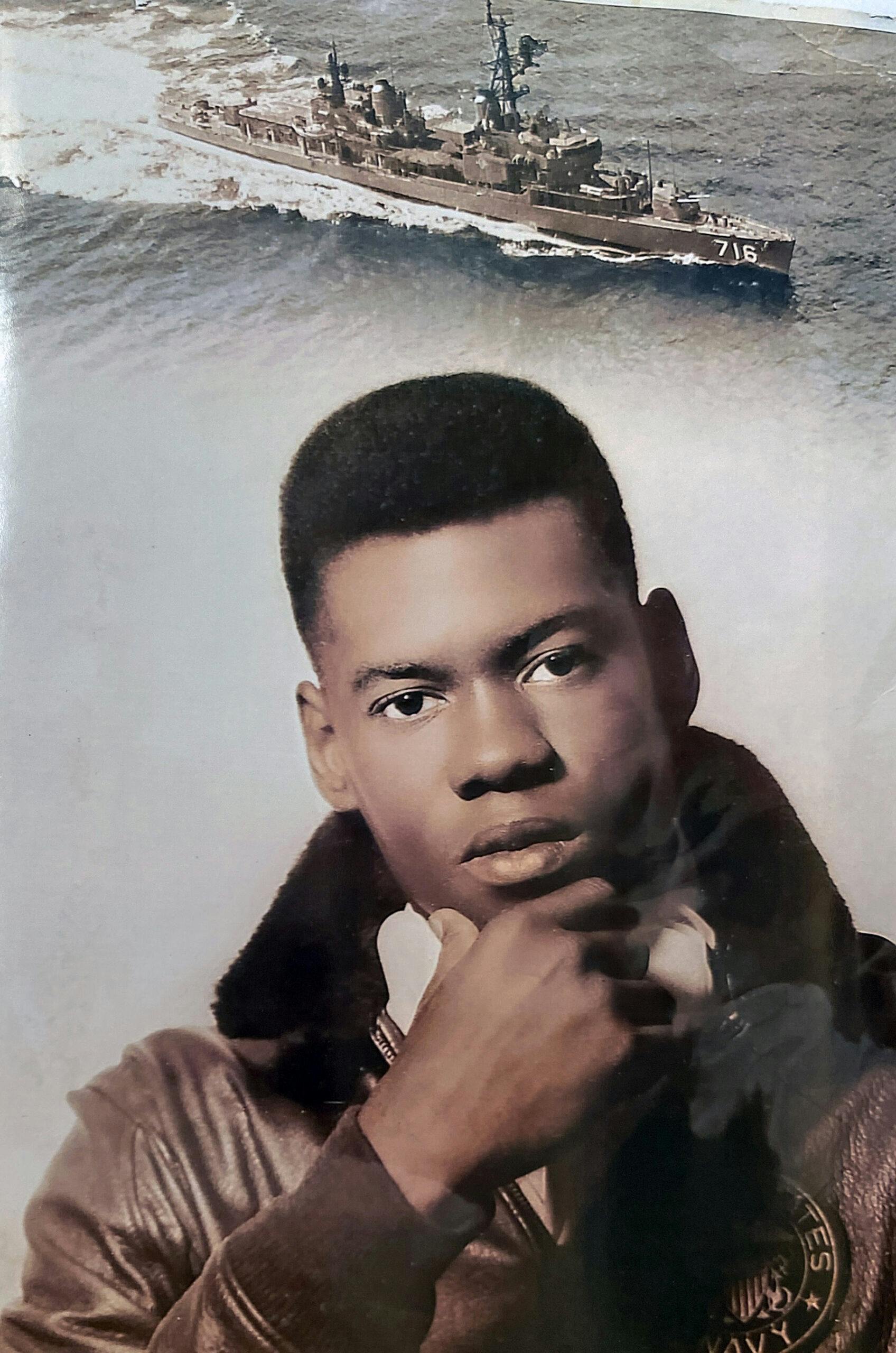

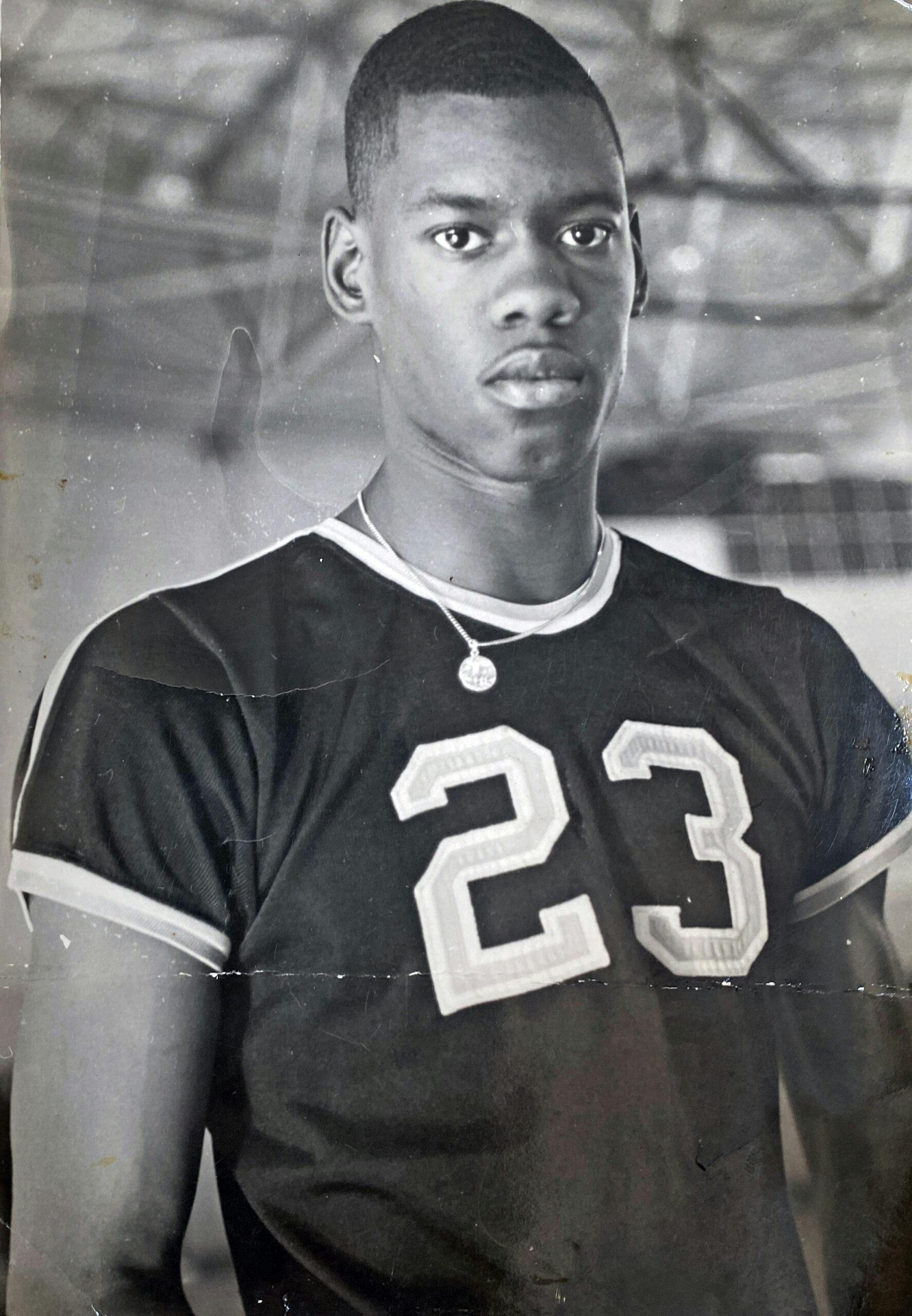

Whether in high school or during his tenure at Louisiana’s Grambling State University, Carter lived his life to the fullest. In one memorable anecdote, he enlisted in the Navy with his friend during a night of partying. Shortly thereafter, Navy recruiters tracked him down in Grambling to ensure he made good on the promise. That pivotal moment derailed his future potential as a professional basketball player, leading instead to a three-year military tour in the Vietnam War. During his service, Carter earned the National Defense Service Medal and the Vietnam Service Medal.

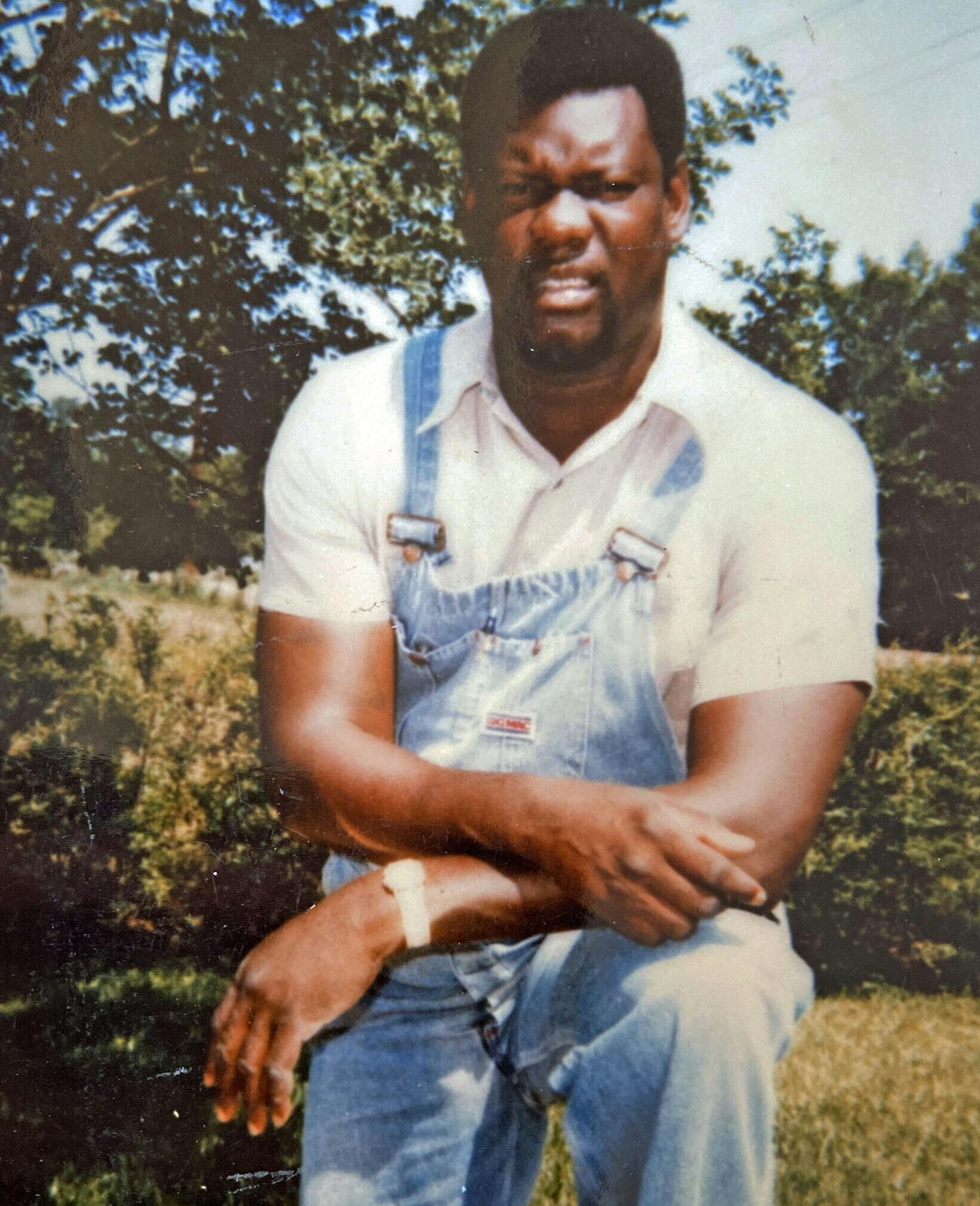

Carter’s time in the service made him look forward to life as a private citizen. Following his homecoming, he worked the next 35 years as an engineer at International Paper. His earnings allowed him to follow his passion for automobiles. Not brand-new ones, but models needing a little TLC that suited his sense of style.

Carter also bought trucks, which were necessary for grunt work on his properties and farmland. It’s clear that he took pride in working with his hands, ensuring his property was as pristine as his many Cadillacs. One does not imagine he wore any of the stylish suits in his closet while driving these rigs, but these days, oddly enough, the trucks are perhaps the most valuable pieces of his automotive estate.

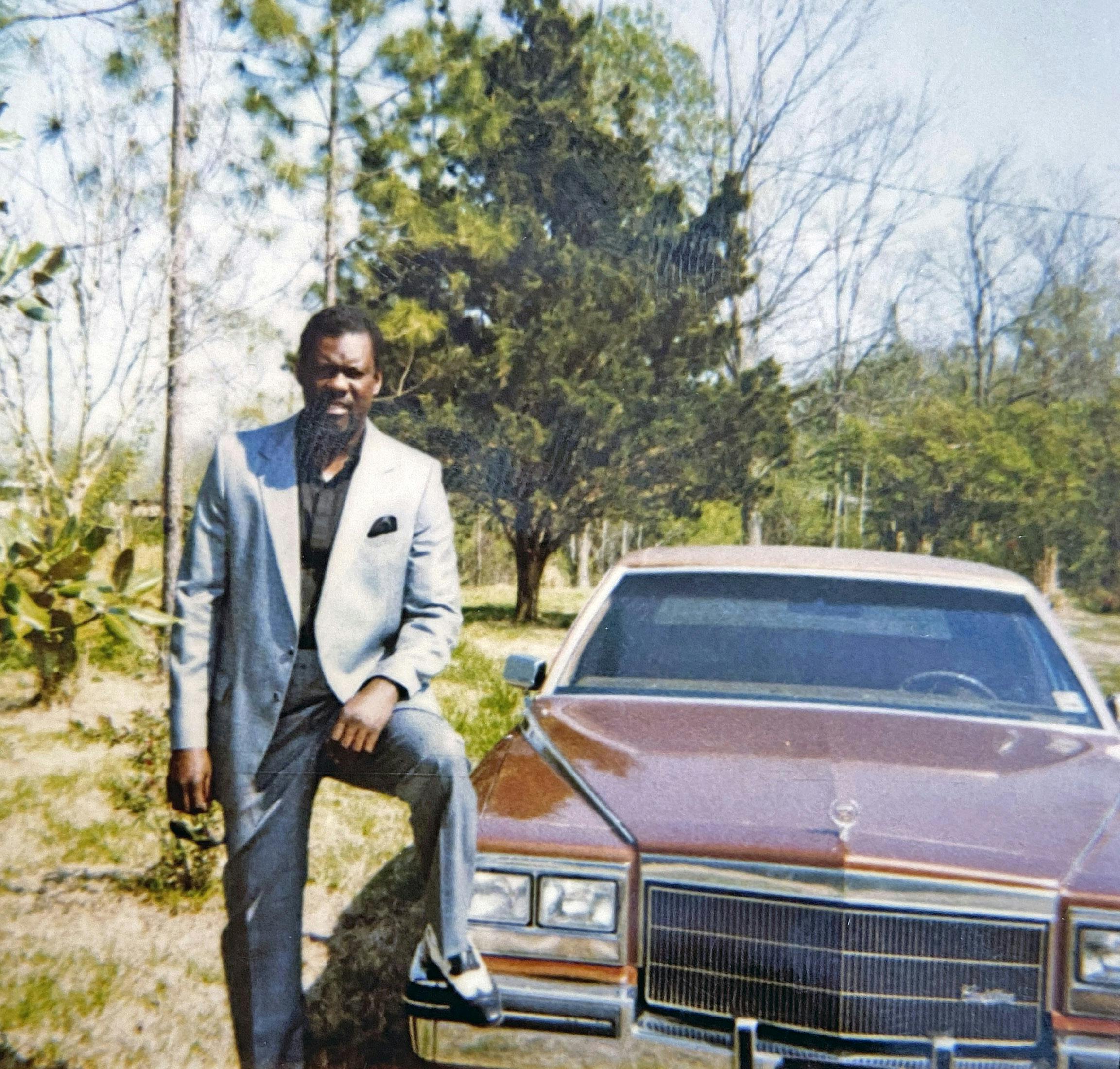

About those suits: The former basketball player must have made quite the splash in Central Louisiana, dressed to the nines and rolling up in a shiny Caddy. It’s sad to see the cars in their current state, even more so that someone is removing parts from them; some of these Cadillac trim bits are pricey on the secondhand market.

From a certain perspective, Carter’s is an American success story, one made possible by a good middle-class job typical of the era. These cars were the mementos of his life, each an individual moment reflecting a life of both charm and, on the flip side, tragic self-absorption.

Linda introduced me to Lester, one of Carter’s neighbors, who noted that “Carter didn’t talk with people he didn’t like, because he didn’t need to.” Lester suggested that Carter didn’t let many folks look at his car collection, and that he amassed such opulence because he could “squeeze a dollar bill tight.”

That might be why, after losing indoor storage, Carter moved his collection of cars and trucks outside. They sat, out in the elements, for decades. As his health deteriorated, the collection went from resting to outright rotting. You could say the same of his relationship with his family, Linda says.

She chooses not to canonize her deceased father. Her priorities just couldn’t be any further away from his. Still, her love of cars came from attending local car shows with him, and from her childhood Matchbox collection. “I loved my dad but I told him I didn’t like his selfish ways. But I am lucky that I was able to tell him I loved him before he died.”

The Louisiana sun was brutal this summer, but I promised to help Linda appraise her father’s collection. So I visited the property early, whipped out my laptop and used Hagerty’s Valuation Tool to provide a reasonably accurate assessment of the vehicles that remained on the property.

Just seeing Carter Rhodes’ collection in person was breathtaking. You don’t get to see cars from the 1970s (mostly) en masse very often, no matter their condition. I can only imagine how impressive it must have been before nature took its toll.

Linda was right, though. The unfortunate present-day condition of the cars ensured they weren’t worth paying for a professional appraiser. Instead, I ran a fine-toothed comb over all the dirty, discarded metal, downloaded relevant data from the Hagerty Valuation Tool, and emailed them to her.

Of all the cars I saw that day, most impressive was Carter’s black Lincoln Continental with the coveted Fixed Glass Moonroof option. He clearly loved this vehicle more than the others; it remained under a carport, parked on a gravel surface so it didn’t sink completely into the ground.

Other cars weren’t so fortunate. Most of these once-dry southern cars would be potential nightmares to restore. That’s not to say some couldn’t be turned into respectable machines with a little bit of money and a lot of labor, but the air there is thick with missed opportunity. Carter’s dark blue Mercury Marquis coupe was one such disappointment. In the 1970s, it must have been a stunner with those swank Cragar rims.

More than anything, what truly surprised me was how many flagship sedans from multiple automakers were accounted for there. Be it a Buick Electra, a Mazda 929, or a Mercury Marquis, Carter knew what he liked. One of them even survived surprisingly well outdoors—an early 1970s Marquis Brougham sedan that looked nice enough to need nothing more than fresh fluids, new tires, and a gentle clean in order to be a sweet runner.

Carter’s collection paints a picture of a man who sought status in his cars and purposeful utility in his trucks. Those trucks now sport handsome patina, at least for the restorers who enjoy that aesthetic. But even Linda was surprised by the number of Lincolns compared with Cadillacs and pickups found on her father’s property. She “always saw him in a Caddy,” even when she was a kid.

It’s unclear how many of these cars will see anything but the business end of a crusher. Linda admits that if her father saw the cars in this condition, it “would hurt him” because he grew up with nothing. Carter, the eldest of 10 siblings, experienced a disadvantageous upbringing. Merely gazing upon his collection gave him a sense of accomplishment that few of us can appreciate.

Linda said that her father still spoke lovingly of his cars on his deathbed. She’s pragmatic enough, however, to understand that he was both a collector and a hoarder. In his 81 years on this earth, Carter wanted cars, clothing, collectibles, car parts, and even valuable scrap metal, as he was a firm believer in the Salvage For Victory campaign.

Linda’s passions lie elsewhere. She offered to show me them, picking me up at my hotel for a drive through her community. There was something about her triple-black Town Car Signature Series, waiting outside the hotel lobby, that felt like an apple not so far from the proverbial tree.

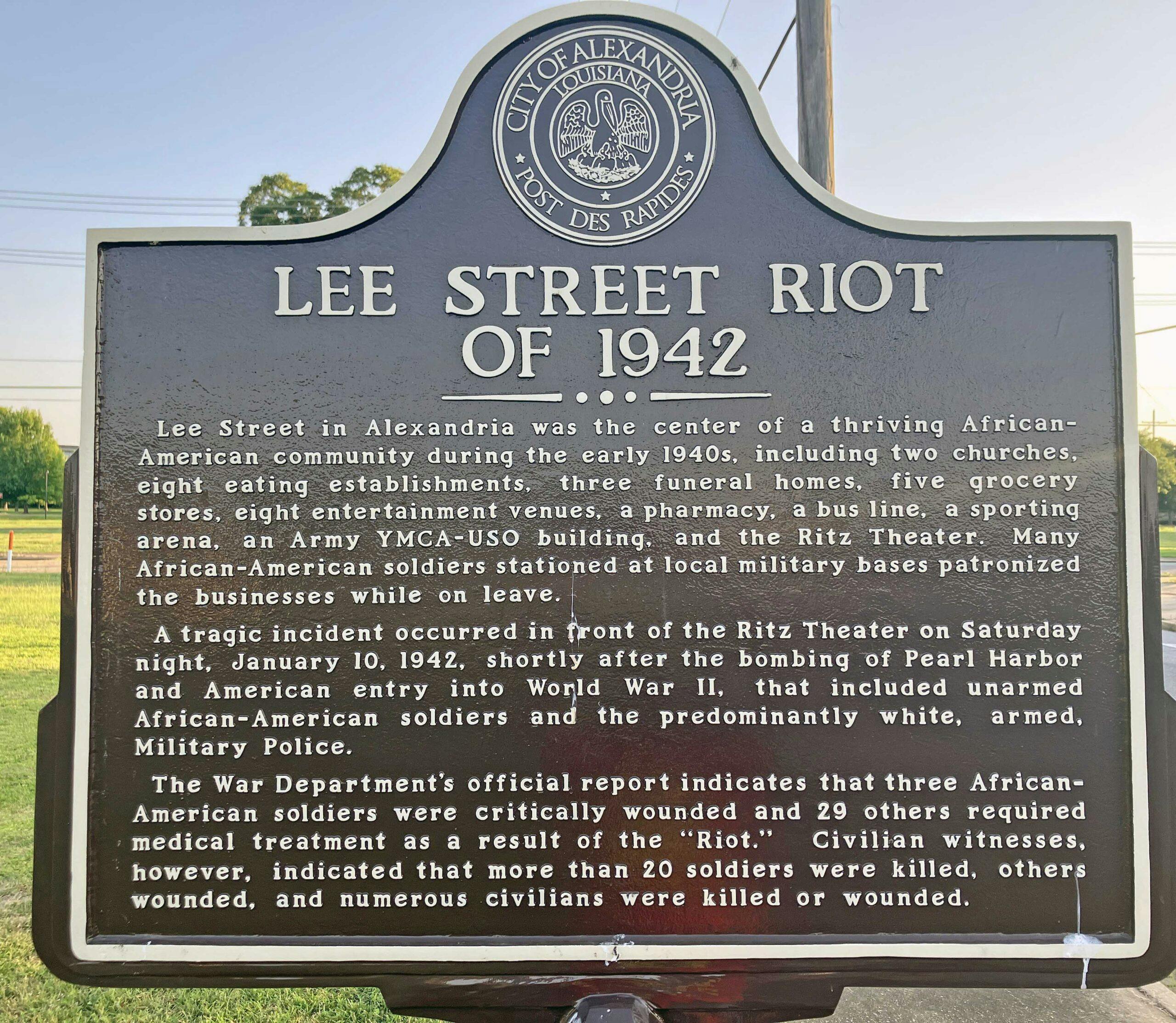

The Lincoln transported us to an important place for Linda, for local members of the Buffalo Soldiers Motorcycle Club, and for many citizens of both Alexandria and Pineville, Louisiana: the site of the 1942 Lee Street Riot.

Linda first learned about the Lee Street Riot from her grandmother, who was there at the time and was “warned not to go out on that day.” The silence of these grass fields adjacent to downtown Alexandria, once abuzz with activity, was somber and eerie.

Some people say that healing only happens once denial ends. The pain from Lee Street inspired Linda to do more than just “walk around like nothing happened.” Her house is close by, and she wanted to learn more about this largely forgotten moment in Southern history. As she asked around, Linda learned that most folks preferred to take stories about the riot to their graves. Her interest was eventually recognized by the local Buffalo Soldiers Motorcycle Club, which encouraged her to keep digging. Around the same time, the City of Alexandria’s government recognized the need to discuss and memorialize what happened on Lee Street, erecting a historical marker in 2021.

Linda, the Bayou Peacemaker, aims to be a force for good. For repair, rather than neglect. She pivoted from her years as a quality control inspector for a local pharma company to a historian seeking long-forgotten truths. We took a trip to the Louisiana History Museum, a place that covers history from multiple perspectives, and the museum’s curator knew Linda. Their back-and-forth banter on Central Louisiana history was enlightening for this outsider.

Once her father’s estate is settled, Linda knows she’ll be due a much-needed vacation. Turning his collection of cars, clothes, and collectibles into proceeds that can go to good use in and around her community is almost a full-time job. The Bayou has bigger plans for everyone and everything.

This is a beautiful well written tribute to Carter Rhodes’ life I am happy to have known him.

LINDA, Your efforts are very noble.