Media | Articles

The last train home

It was ten after eight in the morning, and I was already running late. Cans of high-temp enamel spilled from a plastic bag to the floor of my car as I whipped a turn down my father’s narrow drive. An anxious voice whispered in my head: Just get it done, and you can get on to other things.

The barn door rolled up into the ceiling, clattering as it went. Behind it, on a stand about chest high, was Dad’s beloved mid-1990s Allen Mogul locomotive. The 400-pound, one-eighth-scale, rideable steam engine had been in hibernation all winter, marinating under a husk of dust and grime. It sorely needed a spring reawakening, a fine-tuning and refinishing … and a few fresh coats of black paint.

A familiar phrase wafted through my mind.

I wish it were a sports car.

Rewind to a few months prior. Middle of spring. Mother Nature chose to dump a foot of snow for winter’s last stand in Northern Michigan, and my rental home was ill-equipped to handle it. Worse, the house sat at the end of a long and looping driveway. Neither a half-day of shoveling nor forking over a wad of cash to a random local felt appealing, so I called in an audible.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Dad said to call any time, but I never had. I had stubbornly managed to survive nearly an entire winter on little more than quality snow rubber and momentum. My luck had run out, though, with that last storm. He arrived with the right gear for the job. When the work was finished, the driveway was cleared. All I had to do was ask. But part of me knew why I hadn’t all along.

“You know … ”

Here it comes.

“As payment, you could help me out by repainting the locomotive.”

“You’ve got Venmo, right? Was gonna send you a few bucks.”

“Nope.”

“I’ll set that up for you.”

“Don’t bother,” he said. “Could always use the help, though, with the paint. You’ve got an eye for that sort of thing.”

“You sure?”

“I am.”

“Alright, then. Next time.”

Next time. If that phrase were currency, it would be one of the most devalued in history, uttered by anyone trying to slough off commitment. Ten years, seven cities, three schools, and an immeasurable string of online dates into early adulthood, and my knee-jerk response to the idea of a day with my father was, “Next time.”

As he turned to go, it hit me: My “next time” no longer meant anything to him.

The cruel truth about coming of age is that you don’t get an accurate barometer for the passage of time. There’s no actual perspective with it until that magic day when you’re suddenly somehow old enough to see clearly but unable to get a refund on what you spent. Even then, you can carry on thinking time is abundant when it’s clearly not.

Moving home to Michigan a few years ago was quite a surprise. Finally being in a place to make time for him, his hobby—that steam engine—was another.

I poked at the Allen a bit more, thinking about the work it wanted. How many times I had wished it was something else.

Locomotives are incredible machines, fascinating if you stop to think about them. But who does, any more? “Live steam” enthusiasts are the culprits, and I’ve always struggled to understand them. This dwindling crowd commemorates the old ways. They’re often just passionate machinists, historians, or retired railroad engineers, and their affliction lacks the spectacle or fanfare of other transportation hobbies. Regional groups abound if you know where to look. Spotted in the wild at a Denny’s, they’d most closely resemble a C5 Corvette owners’ meet, if the striped engineer’s caps, denim overalls, and rawhide gloves weren’t a dead giveaway. Enthusiasts meet up by hauling machines to each other’s rail yards—sometimes literally rails in a suburban yard—but that’s rarely an every-weekend affair.

Train folks are generally quiet and private. More often than not, these are hands-on homebodies willing to spend breathtaking amounts of time and cash transforming personal property into the railroad scene of their dreams. Dad is no exception. And really, all the lifted thumbs and big smiles are best spent on parking-lot people. Cars and Coffee meet-ups are always poppin’, but Trains and Tea won’t draw a crowd any time soon.

Alas, that fact means that most locomotive enthusiasts willingly build bridges to nowhere, steaming on with no guarantee of the preservation of a legacy. When they go, their machines often go as well, scrapped or left to rot on display. That bitter crossroads is common in car circles, but in loco-land, the effect is tenfold.

Not to be bleak. There’s always the chance that an outsider will stumble into the hobby and “get it,” at least enough to keep another’s passion or engine going. But if a live-steam enthusiast finds a successor, it’s generally because they’ve plucked that person from the crowd early on, recognizing their particular bent in another and knowing how rarely it comes around.

“Ready and waiting for you,” Dad said.

I turned, half-startled, pretending to have been in the middle of something.

“Got tack cloths?” I replied. “Forgot them at my place.”

“Sheesh,” he said. “Give it a good scrubbing first, will you? Don’t rush it.”

“Right, duh … Of course.”

I slinked off to mix up a bucket of soapy water, mildly embarrassed. When I came back, Dad was peering down into the boiler.

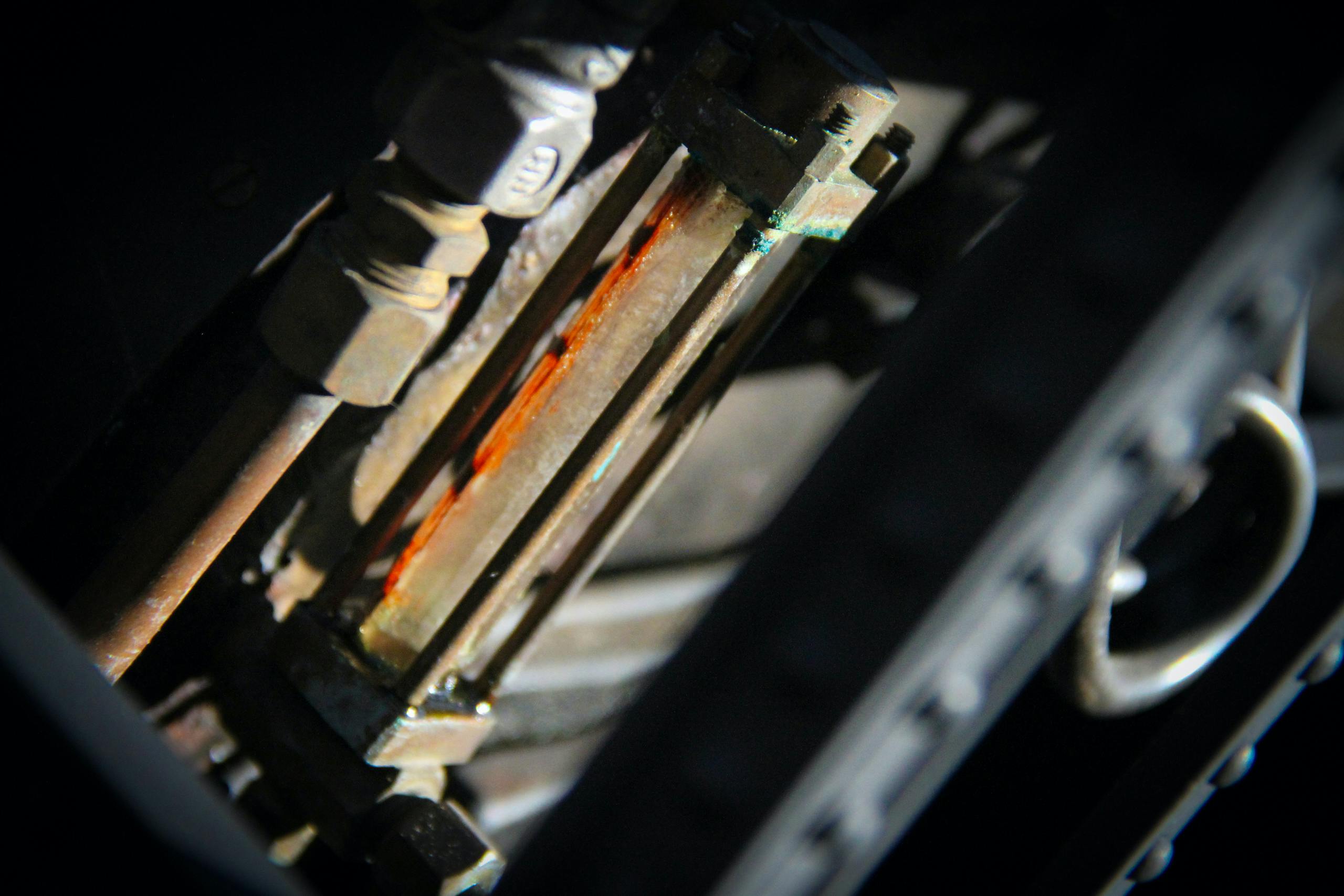

“There’s some corrosion in there. More than I’d like to see.”

“Is that normal?”

“Yep. Let’s plan to dissolve that, though, and then we can pressure-blast the crap out of it.”

I peeked into the cavern.

“A buddy told me vinegar ought to do the trick,” he said. “It likely won’t need anything stronger. Hopefully not.”

“Want to start now? I could always come back to paint; the weather’s been warm enough to—”

“No need. Let’s tackle it when the time comes.”

He handed me an old scrub brush, and I plopped it into the bucket of suds.

A half-hour later, the locomotive was looking better. My curiosity began to take over. Dad was nearby, stealing glances at my progress while tinkering with one of his smaller, HO-scale model rail cars.

I picked at a rectangular hunk of metal with an old toothbrush. “What is this thing?”

“Steam separator,” he said, looking up. “Actually, right there is where your steam enters the lines.”

“But something’s missing? Or … ”

“The steam dome. It’s detached for now, but hit that too, clean it. Don’t forget.”

I pointed into the opening. “And what about this plate area?”

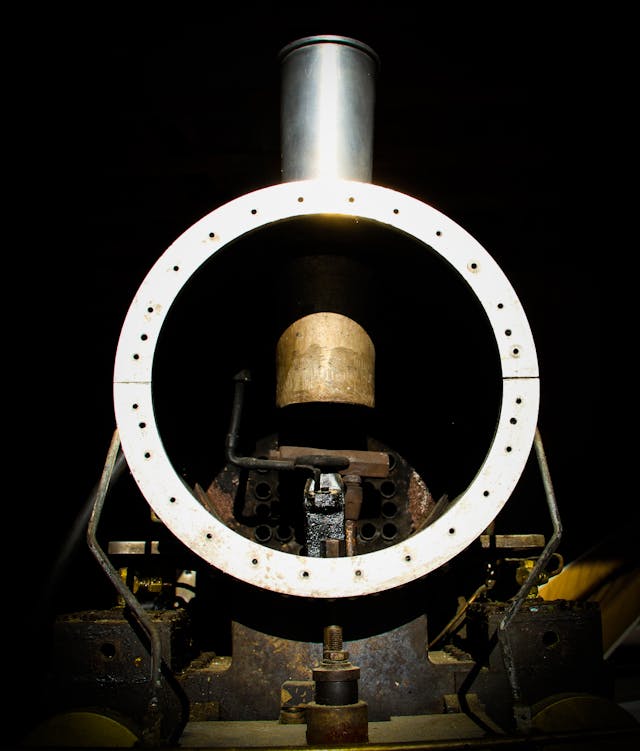

“That’s the front of the smokebox. You won’t be painting that. Pretty cool how you can see down in there now, though, huh? The blower. And blastpipe.”

Blastpipe: pipe where the blast goes. How exhaust steam from the drive cylinders is carried back up into the smokebox. Peering into it is like looking down the barrel of a small cannon.

I glanced back at him. “Melts faces, eh?”

“Raiders of the Lost Ark.”

“Get outta here.”

“Wouldn’t feel good. I’ve certainly never tried it.”

He set down the HO bits and walked over, enthusiasm building.

“When it all runs, used steam and smoke have got to go somewhere, right? Chuff, chuff, out the stack she goes.”

“But usually, this is all enclosed, so …”

“Exactly. That vacuum effect draws more smoke and air in through those pipes, from your firebox, restoking your fire. Neat how it works, isn’t it?”

“Yeah, that’s … really slick, actually.”

I turned his words over in my head for a moment, got stuck on one. “Firebox?”

The question tipped the scales, triggering a semester’s worth of Locomotive 101. These engines are essentially large teakettles on wheels. They need fuel, fire, and water. A trailing rail car, called the tender or “coal-car,” houses an extra water reservoir and fuel. Common steam-locomotive fuels include wood, coal, or, more traditionally, oil. On rideable scale models where an inch of model can equal one foot on the real thing, propane gas is the cleanest option and a convenient go-to. Coal is the most authentic fuel of all, burning hottest with the highest BTUs, but it requires an exorbitant amount of soot cleaning and maintenance after each run.

The firebox is the heart. It lives inside the boiler, producing the thermal energy for converting liquid (water) to gas (steam). Think of it as an oven surrounded by a chamber of water; pressure builds as the water boils. A steam engine’s water level is critical—if it drops too low, the boiler can overheat, causing catastrophic damage. Operators use a sight glass in the cab to judge where internal water levels are settling.

No steam engine is a turn-key operation. Even smaller ones can take hours to reach operating temperature. The actual figure varies with engine size and application, but temps play a pivotal role in efficiency.

Dad waved a hand at the boiler. “When a steam engine is running properly, the smoke is always white, or you can hardly see it at all.”

“Sort of defies popular convention, doesn’t it?”

“Well, when you see them in movies, they’re puking black smoke like that for effect. Or it’s because their fires aren’t hot enough, or they’ve been working the engine so hard that the fire can’t keep up.”

“Rolling coal, locomotive-style?”

He laughed. “A little different, almost the opposite, but let’s roll with it.”

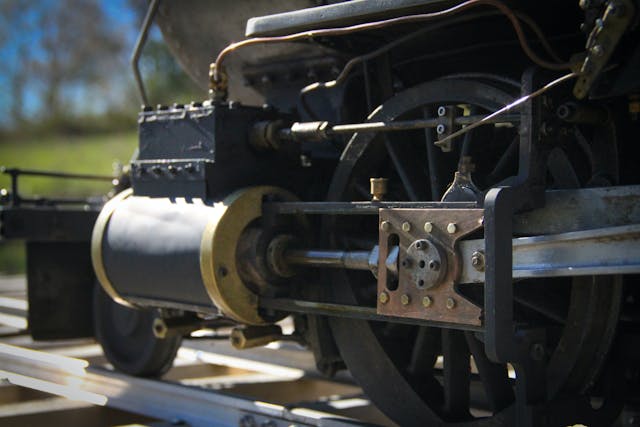

As steam pressure builds in the chamber, that energy wants a place to go. There are usually a couple of safety valves on the boiler and a pressure gauge inside the cab, safeguards so things don’t accidentally kaboom. Otherwise, the engineer’s throttle lever gives control over the intake under the steam dome. When open, it sends pressure—120 to 125 psi in the Allen—into copper lines that run to a pair of front-mounted drive cylinders.

Those cylinders harness the steam and put it to use. Each holds two chambers, one over the other; the upper holds a valve that slides back and forth, and the lower carries a piston connected to a drive rod that is, in turn, connected to the locomotive’s wheels. As fresh steam forces its way into the upper chamber, the valve determines where that steam will enter the lower chamber, placing the pressure in front of or behind the piston. The result is a mighty pushing or pulling of that piston, and turning wheels. In the same motion, “used” steam is exhaled from the cavity. Repetitively done, that evacuation of pressure creates the classic kish-shoo-pa-pa rhythm that steam locomotives are known for.

As with all mechanical marvels, timing is everything. Ideally, each piston stroke produces a perfect half-turn of the drive wheels, with a complete revolution in a single push-pull cycle. As force transfers into those wheels, energy returns to the upper valve, helping repeat the entire process through a part called an eccentric.

“Those rods and eccentric gears, they have to be within certain tolerances, really well-honed, there can’t be a lot of slop.”

“How do you know when something’s not quite right?”

“It’s like an old car in lots of ways. After a while, you learn its language, feel how it’s behaving and hear what it’s saying.”

Another device in the cab, the Johnson Bar, commands forward, neutral, and reverse. It does this by altering the eccentrics, which dictate the travel of that valve inside the cylinder’s upper chamber. Throwing the Johnson Bar all the way forward—all the way open—generates the most power and momentum, but that setting isn’t the most efficient.

“A common engineer’s trick was to make the most of the steam. Pulling the Johnson Bar back toward neutral kept the engine’s moment going but didn’t waste as much. They called that position the ‘company notch.’”

I carefully taped off every line, valve, and strap that didn’t need paint. The many little copper and brass components called up more questions about the machine, now nearing its 30th birthday. Many live-steam models out there are much older.

“Who even makes this stuff nowadays?”

“A lot of it’s DIY. It’s a great way to get into metal work, but most guys have been doing this kind of thing for years. I have Gene to thank for a lot of my stuff.”

Gene Allen was a pioneer in the community. He started Allen Models in 1963. He made live-steam castings, parts, and designs, but more important, he made them accessible, sharing and selling those things to help further the hobby.

“Allens aren’t the flashiest locomotives in the hobby, but the customer support on them is a dream. Especially on ours, the 2-6-0 Mogul.”

Those numbers are known as the Whyte Notation—in the Mogul’s case, the number of wheels that are leading, driving, and trailing, in that order. Frederick Methvan Whyte was a Dutch engineer transplanted to the United States. First publicized at the turn of the 20th century, his notation system standardized how locomotives were classified. Leading wheels guide the engine through a turn or a rail transition, to aid against derailing. Driving wheels support and distribute the boiler’s weight, and the physics of that dynamic help traction. Dad’s Mogul model has no trailing wheels—they aren’t essential for a locomotive’s basic operation, so they are left out of some designs.

“4-6-2 is a Pacific, 4-6-4 is a Hudson, the 2-8-2 is a Mikado, and a 2-8-4 is a Berkshire; 4-8-4 is a Northern … ”

He could go on all day. Let’s recalibrate.

“It’s ready,” I said. “Don’t you think?”

“Looks like it.”

The engine cleaned and wet-sanded, I broke open a pack of tack cloth and laid down the first coat of paint. By the time we found a few chairs and broke for lunch, it was close to noon. I took one last glance before we sat down—the engine was actually beginning to look like something.

After lunch, I sprayed the remaining two coats of black while Dad disappeared into the woods near the house. And just like that, my obligation was over.

The endorphin high of relief I’d been looking forward to never arrived. On the contrary, I was left feeling oddly incomplete.

I left the engine to bake in the mid-afternoon sun and walked out to the trees, following the sound of a whirring compact drill. Dad was replenishing weathered rail ties on the wooded stretch of track behind the house. He looked up.

“You finished?”

“Yeah.”

“Drive in a few?”

“Sure, why not.”

He handed me the drill. I pulled a fresh lumber tie from a five-gallon bucket and burrowed it into the open space under the rail, filling the gap where the old tie had been. I followed the pattern on the other rails, sinking the screws so each fastener head caught the edge of the rail, locking it into place.

“How hard do you sink these?”

“Not very. Each screw needs to be seated enough just to hold the track in place while allowing for some flex and slide in the rail.”

“Is there a torque spec?”

“Just feel. I trust you.”

I backed my screws off a half-turn and continued down the line, replacing more ties.

“A lot of balancing and settling occurs in the track when it first goes down, but every year after, you tweak it less and less.”

I looked down the line. The whole layout must have held well over a thousand ties. All hand-cut from the kind of planks you’d find at your local lumber yard.

We decided to walk the tracks for a bit.

“Oh, I’ve got to show you this,” Dad said, proudly.

We came to a tunnel enclosed in old sheet metal. It looked like some charming little backwoods moonshine distillery.

“The metal is all reclaimed. That was a good find. I love the natural feel. Unlike the big railroads, we get to have a little fun. They had to find the most cost-effective path of least resistance; we can build pretty much anything we want.”

He was right, it was nice. The new tunnel made for a total of three on the property. There were also two bridges. A short while later, we emerged from the tree line, into a view of the barn and the locomotive below.

“What happens to it all … when … you’re … you know?”

“All I know is, when you’ve got kids, if you’ve got to sell the steam engine, at least get a diesel. Then you can get on, turn the key, and go.”

Not a chance. He’s laid the tracks. Following them is the easy part. Or the hardest.

“At the end of the day,” Dad said, “it’s a thing. A material thing I can’t take with me. I would if I could, but I can’t. Above all, it’s more of a joy for me to watch a little kid’s face light up, as mine did once. It’s not any ride you’ll find at Cedar Point, but it’s more than that. It’s ours, on family land.”

“I hear you.”

“You better go tuck her away,” he said, pointing back across the yard.

“Alright. Hey, Dad?”

“Yeah.”

“Thanks.”

“I’m glad you came.”

I was halfway down the hill, headed to the barn, when I heard him call out from behind.

“Next time?”

I couldn’t help but smile at this, at the hope of it, for both of us. I turned and nodded. Then I walked the rest of the way down and slowly wheeled the locomotive back into the barn. The door rolled shut with that familiar clatter. The woods were quiet again. I climbed into the car and shut the door, then wound back out that long drive and made the turn. Leaving home. Heading home.