Media | Articles

If you sold your soul for guitar skills, would you sing about a Hudson?

The ties between popular music and automotive culture are manifold and longstanding. “In My Merry Oldsmobile” was a hit song in 1905, three years before Ford’s first Model T rolled out of Henry’s factory on Detroit’s Piquette Avenue. The song generally considered to be the first example of rock and roll is Ike Turner’s “Rocket 88” (also about an Oldsmobile), from 1951. Many people think Chuck Berry’s “No Particular Place to Go” is really titled “Riding Along in My Automobile,” the opening lyric. In the 1960s, the producers working at Motown’s Hitsville USA studios did the final mix on the singles they hoped to be hits using a simple, full-range 6×9-inch, oval loudspeaker as found mounted in the dashboards of most American cars of the era. The folks at Motown correctly figured that most people would listen to their records on their car radios, so they mixed their songs to sound best in that environment.

Looming large in the history of American music is the quasi-mythical character known as Robert Johnson, sometimes cited as the most influential guitar player of all time.

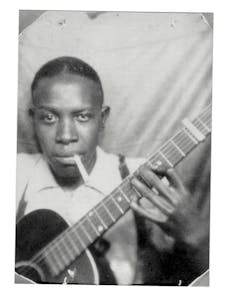

There are only three verified *photographs of the man. While the bluesman himself was no myth, he’s at the heart of one of the most enduring pieces of American folklore. That particular legend starts out with a slightly built teenager trying his hand at entertaining juke-joint patrons with his guitar playing, only to have his “head cut” by older, more experienced professionals. Disheartened, the young man meets up with the Devil after midnight at the crossroads of Highways 61 and 49 near Clarksdale, Mississippi. “Old Scratch” offers Robert unnaturally superlative guitar skills in exchange for his soul. The deal is done and the next time Johnson shows up to perform, the audience and other musicians alike are astounded at the young man’s virtuoso playing, playing both bass and treble strings at the same time. The Devil, as they say, must be paid his due.

At the age of just 27, Robert Johnson died, supposedly poisoned by liquor adulterated by the husband of a woman with whom Johnson was flirting. His burial place has never been verified.

The actual truth, at least according to the extensively documented 2019 biography of Johnson, Up Jumped the Devil, by University of Michigan professor Bruce Conforth and blues historian Gayle Dean Wardlow, is that Johnson had already been working as a professional musician, competent on both harmonica and guitar, from his early teens. If he had a remarkable improvement in his guitar playing after being away from the juke joints for a while, it was because he had spent the time being mentored by guitarist Ike Zimmerman.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Zimmerman apparently preferred the quietude of a local cemetery for the lessons, perhaps the source of the legend concerning the devil. As far as his death is concerned, it’s possible that Johnson was indeed poisoned by strychnine or napthalene from dissolved moth balls, but it’s also possible that Johnson, a heavy drinker who regularly patronized prostitutes and had a reputation as a womanizer, suffered from advanced syphilis. Some have speculated from Johnson’s exceptionally long fingers that he might have had Marfan’s Syndrome, which could have contributed to his death.

While Johnson was influential, and an innovator within the growing community of blues musicians (he played with Sonny Boy Williamson II aka Aleck Rice Miller, and personally mentored Robert “Junior” Lockwood), he didn’t become well known to the wider musical audience until the blues revival of the early 1960s, when Columbia released King of the Delta Blues Singers, a reissue of 16 sides that Johnson had recorded in 1937–39.

To say that King of the Delta Blues Singers changed the course of modern music is to state the obvious. Famed Columbia producer and talent hound John Hammond gave his latest signing, a young Bob Dylan, an advance copy of the album. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, King of the Delta Blues Singers was one of the foundations of the emerging British blues scene. It was probably one of the records under Mick Jagger’s arm when his old schoolmate Keith Richards ran into him at an English train station in 1961, leading to the forming of the Rolling Stones. The Stones covered Johnson’s “Love in Vain” on the Let It Bleed album. Eric Clapton, who as an established star would later record an entire album of Johnson’s songs, Me and Mr. Johnson, as a young guitarist first recorded a Johnson composition, “Ramblin’ On My Mind,” in 1966 with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, and later supercharged “Cross Road Blues” into a blues-rock standard with Cream.

In his three sessions recorded in makeshift studios, Robert Johnson recorded just 24 songs. While many of them, including songs like “Sweet Home Chicago,” “I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom,” “Cross Road Blues,” “Come On In My Kitchen,” and “Last Fair Deal Go Down,” are now blues standards and part of the American songbook, only one of his records was considered even a modest hit when it was released. That song was “Terraplane Blues,” a somewhat ribald song, supposedly about the Essex Terraplane car. Johnson’s double entendres could be taken as either automotive or sensual.

“Who been drivin’ my Terraplane for you since I been gone?”

“I’m goin’ heist your hood, mama, I’m bound to check your oil”

“Motor’s in a bad condition, you gotta have these batteries charged”

“Mr. highway man, please don’t block the road

“Please, please don’t block the road

“‘Cause she’s reachin’ a cold one hundred and I’m booked and I got to go”

That reference to doing a hundred miles an hour might be an exaggeration, as the real Terraplane only had a 70-hp inline six, but weighing just a little over a ton and with a very high final drive ratio of 4.56:1, the Terraplane set a stock-car record in the Pikes Peak hillclimb, giving it the nickname of “hill buster.” Introduced by Hudson in 1932 under the lower-priced Essex brand, the Terraplane was an early attempt at a combined frame and body, what today we call a unibody construction, with the bodywork welded to the ladder frame.

The Terraplane was meant to improve Hudson’s fortunes, the Great Depression seeing the company slipping from third to seventh place among American automakers. It succeeded—so much so that Hudson dropped Essex from the Terraplane’s branding as it became the firm’s best-selling car in the mid-1930s.

While the Terraplane automobile was a big success, the song’s fortunes were more modest. Released on Columbia’s Vocalion and related labels, “Terraplane Blues” sold a few thousand copies, perhaps 5000 in total. The original 78-rpm recordings are rare and collectible. A copy sold for $5200 two years ago. Compared to the modern era’s million selling “gold” and “platinum” recordings, that doesn’t sound like much, but to a itinerant musician like Johnson it was a point of pride. It’s not known if Johnson even knew how many records he sold, as he was paid a flat fee for the three recording sessions he did from 1937 to 1939, and he wouldn’t have received royalties or sales information. We do know that Johnson did enjoy the status that came from being professionally recorded. His records’ modest success with jukebox distributors certainly didn’t hurt his chances of getting hired to entertain at juke joints, “blind pigs,” and private parties.

As you’d expect from the author of “Ramblin’ On My Mind,” Robert Johnson never stayed in one place very long. Starting out as a musician, he’d travel a circuit of venues first by horse-drawn cart, later by hopping freight trains, or standin’ at the crossroad, tryin’ to flag a ride, but sometimes he’d even travel to potential gigs by foot. It’s not likely that he ever actually owned a car, but he obviously admired the Terraplane. While the song’s success was modest compared to the ~280,000 Terraplanes that Hudson sold, it’s likely today that more people know about Robert Johnson and “Terraplane Blues” than about Hudson and its car.

Terraplane Blues by Robert Johnson:

And I feel so lonesome, you hear me when I moan

And I feel so lonesome, you hear me when I moan

Who been drivin’ my Terraplane for you since I been gone?

I’d said I flash your lights, mama, you horn won’t even blow

Somebody’s been runnin’ my batteries down on this machine

I even flash my lights, mama, this horn won’t even blow

Got a short in this connection, hoo well, babe, it’s way down below

I’m goin’ heist your hood, mama, I’m bound to check your oil

I’m goin’ heist your hood, mama, mmm, I’m bound to check your oil

I got a woman that I’m lovin’, way down in Arkansas

Now, you know the coils ain’t even buzzin’, little generator won’t get the spark

Motor’s in a bad condition, you gotta have these batteries charged

But I’m cryin’, please, please don’t do me wrong

Who been drivin’ my Terraplane now for you since I been gone?

Mr. highway man, please don’t block the road

Please, please don’t block the road

‘Cause she’s reachin’ a cold one hundred and I’m booked and I got to go

Mmm-mmm-mmm-mmm-mmm

You, you hear me weep and moan

Who been drivin’ my Terraplane now for you since I been gone?

I’m gon’ get down in this connection, keep on tanglin’ with your wires

I’m gon’ get down in this connection, oh well, keep on tanglin’ with these wires

And when I mash down on your little starter, then your sparkplug will give me fire

*When the USPS honored Johnson with a stamp, they had the cigarette hanging on his lip airbrushed out.