Media | Articles

Hairpin Circus Is Japan’s First Street Racing Movie—But Don’t Expect Tokyo Drift

If you ask most American gearheads about their favorite on-screen representation of Japanese car culture, you’re likely to get a raft of answers naming the usual suspects: Initial D, Speed Racer, or Tokyo Drift’s Americanized take from the Fast and Furious franchise. A few hardcore fans might even name-drop Wangan Midnight, a series about a demon-possessed Datsun Z that’s more obscure outside of Japan but which spawned 13 entries in its home market.

Almost no one will offer up the grand-daddy of Japan’s automotive cinema scene, a 1972 classic that has more in common with modern-day Michael Mann than it does nitrous oxide or mountain touge. Hairpin Circus hails from an era where less was more in terms of what directors chose to put on the screen, at least when it came to dialogue and plot, preferring instead to bask in the reflected glory of a nighttime Tokyo and the souped-up ‘70s sports cars that patrolled its streets.

Featuring cinematography that feels equal parts Grand Prix and Vanishing Point, and characters whose ennui pushes them outside the boundaries of the safe lives they’ve constructed for themselves, Hairpin Circus is an important and overlooked entry in the street racing canon.

Was That A Toyota 2000GT?

Three key components set Hairpin Circus apart not just from its contemporaries but also from its gas-soaked successors.

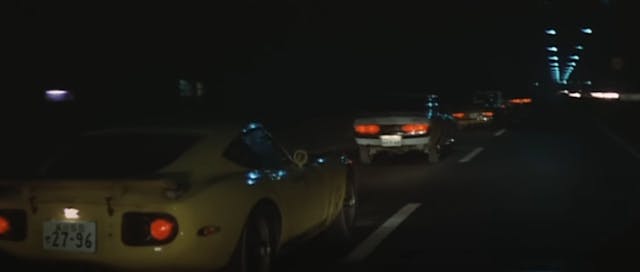

First up are the cars. The hero vehicle, driven by the film’s antagonist Miki (played by Yuko Enatsu) is a Toyota 2000GT, a car whose immense modern-day appreciation requires the suspension of disbelief for its inclusion in a gang of young, seemingly jobless street toughs. Bedecked with a rear spoiler and chrysanthemums petals painted on the door to reflect the number of opponents Miki has vanquished, this was just another used sports car at the time of filming—much in the same way Vanishing Point’s Hemi-powered Dodge Challenger held no special cachet outside of its potential for speed.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The 2000GT is supported by a steel-bodied cast that includes a mid-60s Alfa Romeo Spring GT and a 1971 Toyota Celica GT, each driven by members of Miki’s entourage as they seek out potential marks on Tokyo’s Bayshore Route, the expressway destined to become the epicenter of the city’s top speed runs during the turbocharged ‘80s and ‘90s.

After identifying their victim—and herding them off an exit and into the construction zones and dockyard industrial areas that offer automotive parkour deep into the night—the trio play follow-the-leader until someone loses control and crashes out. In the final sequence, a retired racing driver named Shimao (Kiyoshi Misako) with ties to Miki from before she was sucked into street racing, saddles up in a modified Mazda RX-3 and turns the hunters into the hunted.

Cinematography That Was Ahead Of Its Time

Up next is how director Kiyoshi Nishimura chose to shoot Hairpin Circus’ automotive action. In an era where practical stunts were the only option, the entirety of the film’s street sequences are shot in-camera, with none of today’s adrenaline-simulating special effects layered on top. To enhance the sensation of speed, and further take viewers down the deep well of detachment and escapism soaking through the lives of each character, Nishimura favors long exposures that sear Tokyo’s streetlights and neons into the retina, while also attaching cameras to several of the vehicles seen on-screen to provide bumper, roof, and rear spoiler perspectives on the action at hand. Of particular note is some of the first use of now-common shaky-cam, adding to the furtive nature of the footage and making it seem almost as though the movie is being stolen straight from the city’s streets.

Long sections of the film are given over to the simple act of driving, whether it’s the aimless scouting for potential Bayshore action or the extended chases as the cars snake through stacks of shipping containers. Dialogue is sparse, and for all of the heightened reality of its visuals, fantasy occasionally intrudes, as when the 2000GT and RX-3 pirouette across a snow-covered slope to represent the delicate dance taking place between the movie’s two most skillful drivers.

This dreamlike action is contrasted against the more straightforward presentation of on-track competition that was shot during an actual running of the Macau Grand Prix. Shimao’s decision to turn his back on racing stemmed from the death of his competitor and friend during a push to victory from behind the wheel of his Honda-powered open-cockpit racer. Repeated flashbacks treat the viewer to Shimao and others booting down an ultra-tight street course in a wide variety of vehicles including contemporary sports cars and open-wheel formula machines, it’s here that the technique and cinema verite approach call to mind a mix of John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix as well as Lee Katzin’s Le Mans.

Listen To The Exhaust Notes They’re not Playing

Finally, the music. It’s here that Hairpin Circus most directly presages Mann’s 80s and early-2000s Hollywood work, as it marries lingering camera shots with an almost non-stop soundtrack of bebop-flavored jazz. You were expecting rock ‘n roll to score a flick about street racing? Sorry, this isn’t Two-Lane Blacktop (which had been released just the year before) or American Graffiti (which hit screens in 1973).

Everyone we meet in Hairpin Circus is sad in at least one easily identifiable way (death of a friend, trapped by gender roles), alongside a more subtle variation on that emotion (trading their true passion for domestic stability, an inability to connect with the person they love). Loop that back to the expressions of Japan’s counterculture that permeate the movie, including post-hippie drop-outs and a title-tied subplot about model airplanes, and jazz is the perfect metaphor for the loose, flowing energy that links together each character and their passion for life behind the wheel.

“Do you have something in your life that you live for?” Miki asks Shimao, who we learn was her driving instructor when she first got her license. It’s a question that he can’t answer until the very end of the narrative, when the death of an innocent as a result of her street racing antics jolts him awake from sleepwalking through his own life. Putting aside his fear of his own racing skills, he answers the call to end the reckless pursuits of her gang by using their love of speed against them.

An Overlooked Time Capsule

The movie’s title is called out by a pre-title card montage that makes direct reference to Baron von Richtofen’s Flying Circus, a group of German fighter pilots who were the top aces of World War I. This is how Miki and her crew see themselves, a “Hairpin Circus” as she calls them, whose aces apply their skills to apexes instead of war. Each race is a dogfight, and it’s a zero-sum game where winners drive home and losers occasionally pay the ultimate price.

That conflict from the early 20th century is now more than a hundred years in the rearview mirror, but Japan in the early 1970s was just a generation removed from its own failed imperial conquest, and this was as close as a mainstream Japanese production could get to referencing the martial bond between a group of men and women who live outside society’s experience and expectations. It’s here that Hairpin Circus finds common ground with Vanishing Point, a more isolated tale of estrangement from cultural norms, as well as the first Fast and Furious film where Dom Toretto’s crew form family bonds in the face of a larger world that doesn’t slow down to take note of their all-consuming passion for cars.

The entirety of Hairpin Circus is available on YouTube, with English subtitles provided to guide you through the dialogue that occasionally breaks through the action. At a brisk 84 minutes in length, it’s more than worth taking a trip back to a time before we lived our lives a quarter mile at a time. JDM fans will salivate at the classic metal being thrown around on screen, esthetes will fall in love with images of a Tokyo that no longer exists, and nearly all of us will resonate with how unfinished business from our past played a part in who we’ve become today.

I’m going to give this a watch. 70’s style and a 2000GT, I’m in.

I’m watching Hairpin Circus right now, pretty groovy baby.

In the movie “Vanishing Point,” the iconic 1970 Dodge Challenger R/T featured a 375-horsepower, 440ci Magnum engine paired with a 4-speed manual transmission and Hurst pistol-grip shifter

I just watched the movie. The cars are interesting except I didn’t notice any Datsun 510s, which was the car I bought coming home from Vietnam in ’72. I had read about the 510 in Car and Driver magazine and I wanted to go autocrossing. What surprises me is how much Mr. Hunting could write about the movie, I guess that what makes a writer.