Media | Articles

50 Years of American Graffiti : The cars, the music, and the everlasting impact

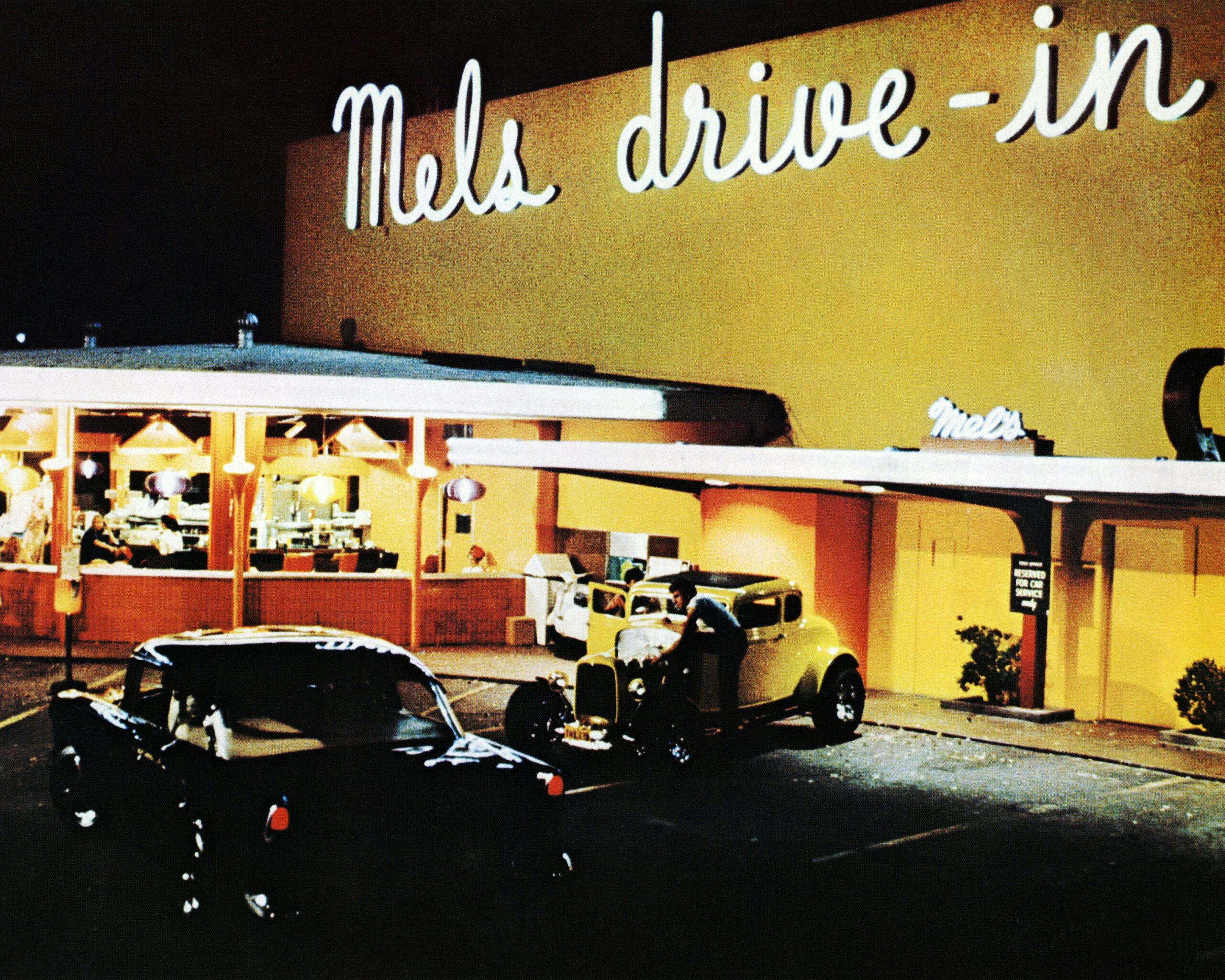

George Lucas’ cinematic salute to midcentury cruise culture opens with the jumbled chirps of an AM car radio being tuned, like the pit orchestra warming up at an opera house. Then, as the curtain lifts on a sunset scene of Mel’s Drive-In, the soundtrack locks on to Bill Haley and His Comets belting out their famous 1950s pop anthem, “Rock Around the Clock.” What follows is a 112-minute comic opera of love, longing, joyriding, and high school restlessness that takes place over a single night and is set to a nearly nonstop soundscape of ancient jukebox hits.

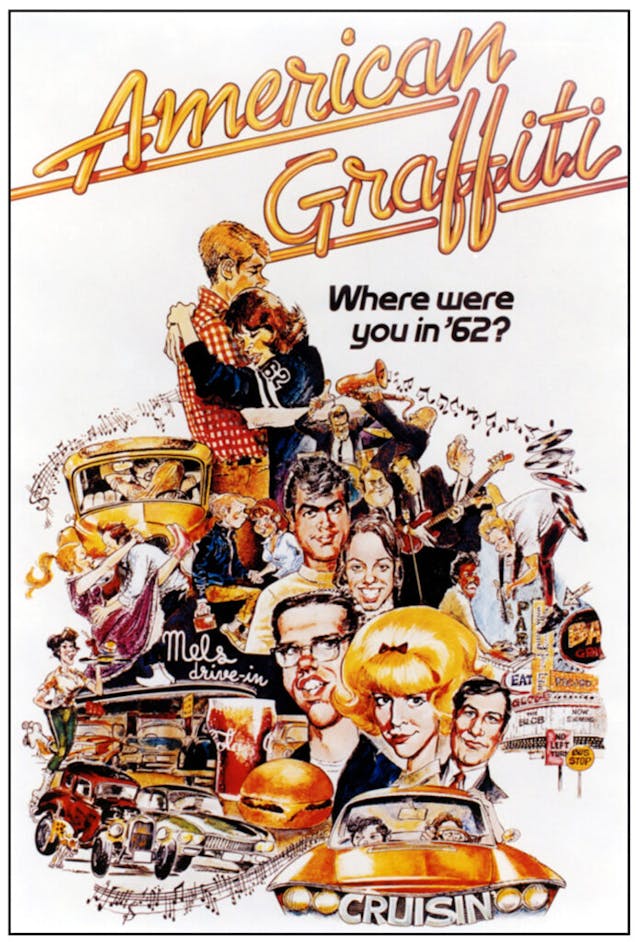

“Where were you in ’62?” asked the movie posters when American Graffiti debuted in the summer of 1973. It didn’t matter where you were, because watching the film, whether for the first time or the 40th, puts you right where Lucas wants you to be. Which is in his backwater hometown of Modesto, California, in the last golden days of greasers, bobby socks, poodle skirts, and doo-wop burbling from tinny dash speakers.

Marking its 50th anniversary this year, American Graffiti is often called one of the best car movies ever made. Granted, it’s a low bar; the film catalog, especially from the 1950s and ’60s, is full of lousy car flicks, from Hot Rod Girl to Hot Rod Rumble to The Devil on Wheels. Most were just gasoline porn wrapped in some tin-pot scold against motorized delinquency to please the censors. Few remember them now, while American Graffiti sits on the American Film Institute’s prestigious list of top 100 movies.

It was nominated for five Academy Awards and is thought by some to be the film industry’s first summer “blockbuster,” taking in so much money that it rates as one of the most profitable movies ever made based on its ratio of return on cost. It launched a decades-long craze for ’50s nostalgia and it catapulted Lucas out of impoverished obscurity, making him an overnight millionaire and rocketing him to his next stop in a galaxy far, far away from Modesto.

No mere car movie has that kind of power. Because American Graffiti isn’t about cars, really. Or even the early rock-and-roll that serves as its only musical soundtrack. Those are just the props and the scenery. At its core, American Graffiti is a coming-of-age story, a theme that has sold tickets since Shakespeare’s Hamlet pondered whether to be or not to be. Lucas’ inspiration was to figure out how to tell it with a juiced ’32 coupe and a bitchin’ ’58 Impala as costars.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Fans of American Graffiti have erected more than a few monuments to it online. You can while away many hours watching interviews with the cast and crew or reading Kip’s American Graffiti Blog, which is a dense accounting of film factoids. Such as that the Pharaohs gang “with the car coat and blood initiation” was based on a real Modesto car club called the Faros. And that the small-town Mel’s Drive-In featured in the movie was actually located on Van Ness Avenue in the heart of San Francisco, used because it was one of the last circular drive-ins left in California.

Or that the origin of the whole film was based on a previous flop. Not long out of USC film school, Lucas was advised by his mentor, director Francis Ford Coppola of The Godfather fame, to develop a more lighthearted project following Lucas’s screenwriting and directorial debut, THX 1138. The somber sci-fi potboiler starred a rookie Robert Duvall as a mal-content living in a dystopian future where people with shaved heads and serial numbers for names drone their lives away in an oppressively bland surveillance society. It was a feature-length version of a 15-minute film school project by Lucas, and it was produced by Coppola’s newly created American Zoetrope production company, established in San Francisco to be at the pointy edge of the long-hair, purple-haze, counter-culture film movement.

Rich with ingenuity but perhaps a bit too avant-garde, THX 1138 (which took its title from Lucas’ college phone number, an alphanumeric sequence that reappears throughout his later career, including as a license plate on Graffiti’s yellow ’32 Ford), bombed. According to a box office–tracking site, the R-rated pic currently ranks as the 32,230th highest-grossing film ever. Thus, the young director was keenly focused on commercial viability when he turned to his next project.

His mind wandered to his teenage years in Modesto, a small Central Valley farm town where bored kids cruised the drag or idled away the nights at soda counters and drive-ins, wondering what life was like just over the horizon. Lucas had been one of those kids, turning 18 in 1962 and fixated on cars and racing. He worked at a foreign car shop and blatted around town in a tiny Autobianchi Bianchina with a rollcage and a Maltese cross on the fenders. At least, until he was torpedoed by a Chevy while turning left into his driveway. The crash punted the Bianchina sidelong against a tree, breaking the seat belt and hurling Lucas onto the pavement. He spent his high school graduation in the hospital coughing up blood, and the world came breathtakingly close to not having American Graffiti, Star Wars, and all the rest.

Even so, Lucas never lost his infatuation with vehicles, incorporating some sort of hot rod, interstellar or otherwise, into almost every film. At USC, his senior student project was called 1:42.08 and featured Pete Brock of Shelby Cobra Daytona fame in a Lotus 23 at Willow Springs Raceway in a wordless montage of driving scenes. The best part of THX 1138 is the final eerie chase sequence in which Duvall flees the subterranean city in an “Autojet,” which was a lightly disguised ex-Sebring Lola T70.

Thus, cars and what Lucas called “the particularly American mating ritual of cruising” were destined to be fixtures in his new movie. Trying to immerse himself in the times as he took his first stab at the screenplay, Lucas raided his record collection and spun 45 after 45 of period tunes on his sister’s turntable. The project faced numerous rejections until Universal finally agreed, but only after Coppola’s name was thrown on the table as executive producer. Script doctors Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck, an old USC classmate, came aboard, fleshing out Lucas’ screenplay using their own high school memories. Universal’s purse was tight; the film was allocated a miserly budget of barely $750,000, which meant it had to be shot in a blitzkrieg 28 nights and with a troupe of young actors who were relative unknowns at the time. Ron Howard was the biggest star, having played the freckled tyke Opie Taylor in more than 200 episodes of The Andy Griffith Show. The future Han Solo, Harrison Ford, whose brief role in Graffiti was as the reckless hot-rodder Bob Falfa, was then working as a carpenter in Los Angeles.

As the film begins, the four central characters—class president and popular guy Steve Bolander played by Howard; an undiscovered Richard Dreyfuss as the doubt-ridden beatnik Curt Henderson; rat-racing everyman John Milner embodied by a former amateur boxer named Paul Le Mat; and the gawky nerd Terry “the Toad” Fields played by teen actor Charles Martin Smith—have just been booted from the nest of their comfortable high school adolescence. In one fateful night of cruising, brooding, kidnapping, canoodling, and brawling, they will each try to figure out their path to manhood. “You can’t stay 17 forever,” Steve exclaims to Curt at the beginning of the film, launching the boys on their journey.

Lucas wanted a documentary style and gave the actors minimal direction, encouraging improvisation as the camera rolled. Almost invariably, said the actors in later interviews, Lucas chose the sloppiest takes, believing they were the most natural. Such as in the opening scene at Mel’s when Charles Martin Smith rides up on a Vespa, accidentally slips off the clutch, and crashes into a trash can. In the first minute of the film, this unintentional blooper neatly establishes the character of Terry the Toad as the movie’s bumbling comic relief.

Another documentarian trick—though it was really a cost-saving measure—was to shoot the movie in Techniscope, a cinematography format developed in Italy in 1960 to maximize the productivity of expensive 35-millimeter color film stock. Basically, Techniscope cuts the conventional 35-millimeter frame in half, cramming two shorter frames into the space of one while still preserving the frame width. That allowed Lucas to shoot twice the footage on each canister of film. However, when the film was developed and distributed, its 35-millimeter width allowed it to be transferred to conventional widescreen projection stock. Meaning the images still filled up the theater screen, but at the cost of the blown-up images being grainier. Which for Lucas, who had used Techniscope on THX 1138, was what he wanted anyway for a gritty, realistic style.

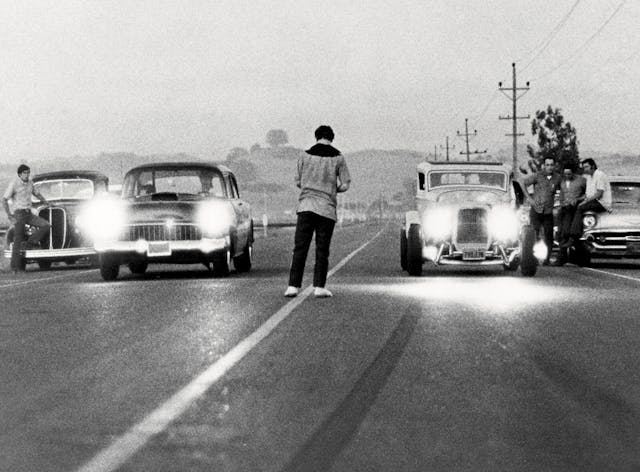

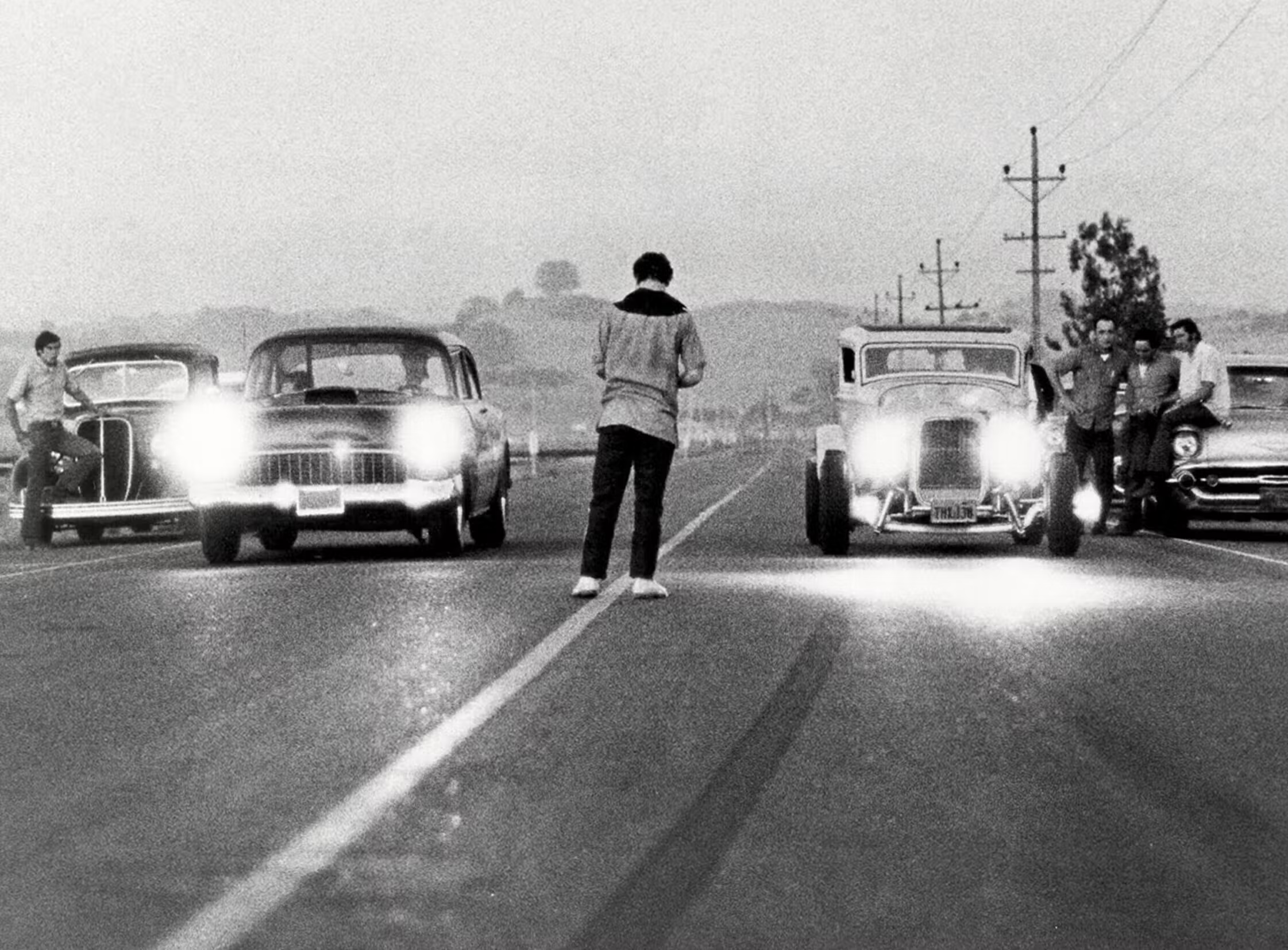

Naturally, there were disasters. Modesto’s commercial drag was considered too run-down by 1973, so Lucas chose the Bay Area city of San Rafael as a stand-in. However, after the first all-nighter of filming, the city tore up Lucas’ film permit and kicked the production out, citing disruption to downtown businesses. The entire operation had to move overnight some 20 miles north to the more welcoming burg of Petaluma, where most of the film was shot. The vintage DC-7 airliner that Curt boards at the end of the movie had engine trouble and was a week late arriving at Concord, California’s Buchanan Field for the scene. Bob Falfa’s ’55 Chevy was a cinematic hand-me-down, having been built for the 1971 road movie Two-Lane Blacktop. Fitted with antiroll bars and a lowered suspension, it refused to roll over on cue in the penultimate sunrise race scene between Milner and Falfa, forcing Lucas to shoot Falfa’s crash in bits and pieces over weeks.

The film is as much an aural experience as a visual one. Lucas’ original script included his insertion of specific songs for specific scenes, such as The Platters’ “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” for the dance between Steve and girlfriend Laurie, played by the late Cindy Williams. But it isn’t just the 41 rock-and-roll hits that wallpaper the soundtrack—from “16 Candles” by the Crests to “Come Go with Me” by the Del-Vikings to “Since I Don’t Have You” by the Skyliners. It was Lucas’ decision, along with his sound editor, Walter Murch, to feature the music—again, documentary style—as though it was heard on a car radio or from some distant jukebox. Thus, the old 45s were rerecorded, but in gymnasiums, between buildings, or out on streets, with the speakers moved around to achieve different distortive effects.

At times in the film, the music is distant and fleeting, as if playing in a dream or a nostalgic reverie. At other moments, it’s upfront to heighten a scene’s emotional punch. And it was Murch’s suggestion to incorporate Robert Weston Smith, aka Wolfman Jack, as an unseen Wizard of Oz figure presiding over his kingdom of teenagers through the medium of radio. Except for the scene in which Curt meets the Wolfman, most of the famous DJ’s splendid contribution to the film was cribbed from previously recorded live broadcasts from the 1950s.

Unlike most films that use atmospheric music to heighten a scene’s tension, Lucas instead went silent in Graffiti’s few suspenseful moments, using the disquieting break in the soundtrack to ratchet up the drama. Such as when Curt, at the behest of the Pharaohs, into whose captivity he has fallen, sneaks under a cop car to hook a chain to its axle. This was partly an artistic choice and partly a monetary one, as Lucas had no cash to commission a unique score. He spent $80,000 of his budget on music licensing alone, working out to roughly $2000 per song. It’s a ridiculously low number by today’s industry standards, and American Graffiti is thus a film that would be nearly impossible to make today. At least, for so little—in part because the movie helped establish pre-released popular music as an acceptable (and profitable) soundtrack source, driving up licensing fees.

Lucas has said that all the characters contained pieces of him, but the one he most identified with is Curt, played by Dreyfuss. Curt begins the film waffling over whether to leave for college or stay behind in Modesto. As the tale proceeds, he’s seemingly presented with a series of glimpses of life’s smallness if he stays, from the juvenile pranks of the Pharaohs to the high school teacher who got out but then failed, returning to a petty existence of flirting salaciously with his students. “Where you goin’?” Curt asks his old girlfriend at one point in the movie. “Nowhere,” she replies. “Well, you mind if I come along?” The white Thunderbird with the blonde that Curt spends the night chasing proves to be nothing more than a mirage, a giddy fantasy that, in the end, he leaves behind as the DC-7 wafts him away to adulthood.

American Graffiti opened in theaters on August 11, 1973, as the papers trumpeted news of the Watergate hearings and the American bombing in Cambodia. Except for San Francisco Chronicle film critic Anitra Earle, who called it “without doubt the most tedious film I have ever seen,” reviewers generally swooned. Los Angeles Times film critic Charles Champlin praised the movie’s affectionate “reexamination of the last hours of settled youth,” echoing others in saying it was “one of the most rewarding attractions of the year.” The public packed the seats, and as late as the following January, fully five months later, theaters were still advertising daily showings.

The cultural impact was immediate. Nostalgia spinoffs in the form of Happy Days and Laverne & Shirley hit the tube, Ron Howard sticking to type as the clean-cut Richie Cunningham. A leather-jacketed Henry Winkler became a household name as The Fonz, all but reprising his role as the kindhearted hood from another ’50s retro set piece, The Lords of Flatbush, from 1974. Fifties-themed diners sprang up across America and singer Billy Joel cut hit songs in doo-wop style.

Meanwhile, as Detroit sank steadily into the 1970s malaise, car customizing experienced a resurgence. The so-called Bubble Top King, Darryl Starbird, who served as a technical adviser on Graffiti (and is mentioned by name in the dialogue), credited the movie with reactivating people’s interest in frenching and pinstriping. “Four or five years ago, drugs and music seemed to be big,” he told his hometown newspaper, the Wichita Beacon, on the eve of a local custom car show in 1974, “but the trend back to cars is coming around strong.” Hot-rod meets started filling up with chopped and hoodless ’32 Fords, everyone wanting to be as cool and unbeatable as John Milner.

It’s hard to believe that only 11 years separates the time period in which the original film is set from the year it was released. We think life moves fast now, but if you released a film about 2012 today, its main defining differences would be iPhone 5s and slower internet. However, so much happened in the world and in the culture after 1962 that Graffiti’s America was virtually unrecognizable by 1973. First John F. Kennedy, then Bobby Kennedy, then Martin Luther King Jr. were gunned down. An unpopular war rang up a horrible butcher’s bill while cities and universities split open in protest and race riots. The Age of Aquarius led to the gloom of Watergate, environmental crisis, and oil embargoes. American Graffiti isn’t just about the end of youth, it’s about the end of innocence, perhaps the one thing that the people who were actually there in ’62 mourn the most.

“Rock-and-roll has been going downhill ever since Buddy Holly died,” grouses the hot-rod hero John Mil-ner as a Beach Boys track briefly interrupts Graffiti’s endless eulogy to the 1950s. Fittingly, perhaps, the film closes with the song “All Summer Long” by the Beach Boys, meaning you can’t hold back progress. “Every now and then we hear our song/we’ve been having fun all summer long …”

Lucas attempted to neatly tie up his story with an epilogue board preceding the final credits that spelled out the varying fates of his four principals. But the film raked in so much dough that a sequel was virtually inevitable. A suddenly very important and busy Lucas—Star Wars, Indiana Jones, founding Lucasfilm and Industrial Light & Magic, etc.—was only involved as an executive producer in the 1979 follow-up, More American Graffiti. It ushered the characters, minus Dreyfuss’ Curt, firmly into the 1960s maelstrom but with less charming results.

Maybe nobody really wanted to grow up after all. That’s the problem with coming-of-age stories; once the characters come of age, you want to hit the rewind and go back to their uninhibited youth. George Lucas did it in spectacular fashion for all of us, creating an inviting multisensory sanctuary that you can curl up in whenever the mood strikes. Because as John Milner declares every time you load up the video, “I ain’t goin’ off to some damn fancy college! I’m stayin’ right here, having fun as usual!” And you’ll always be able to find him at Mel’s, in 1962, having fun as usual.

To this day, the American Graffiti soundtrack serves as the ultimate introduction to early American rock-and-roll, doo-wop, and R&B. It’s best heard on a beat-up triple LP copy or, perhaps better yet, by way of a dusty cassette on rally night. Over 3 million copies were sold in the U.S. alone.

***

This article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe and join the club.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Loved the movie – it was very close to the life I lived in a little burg in Idaho in the ’60s (except real life was a bit grittier most of the time). The music was well-chosen. But I can’t bring myself to feel like some people do, entranced by it all. Same with Star Wars and M.A.S.H. and Jaws – they were really good, and I enjoyed them, but to worship them like some do (e.g. – clone the cars and watch the movie over and over) seems a little creepy to me. That’s just me, though – if that sort of thing is your bag, more power to ya!

Lived in Lewiston, Id. Graduated in ’63. We had “Lew’s” drive in just off main street and lots of action on the gut cruzin, racing across the bridge to Clarkston or out on the 4 lane in N. Lewiston, and the Lewiston Hill road. Lot’s of “Hot Rod’s”. The beginning of muscle car’s, “409’s”, “406 Ford’s”, and others. Going up to Deer Park dragstrip. Good times, with a few bad times to bring us back to reality.

Saw the ultimate date movie more times than I can remember. I just got my driver’s license in 1973. Took my girlfriend to see it. She had not seen it. I lived the life with two 1960 cars. An Impala & a Lincoln. The cruising I did for 3 years was like in the movie. I still do the Saturday night cruise around Toledo now as we did then. Occasionally I see a classic or some new-era muscle cars. We had to buy minimum order to park at McDonald’s & Big Boy etc. Last Saturday night before I left to join US Air Force.1975. We had a Christian youth group meeting. We talked to the advisors to go to McDonald’s for food. Nothing like a Church bus full of teenagers & Muscle cars, classics. One car is a good memory. A mechanic took a Chevy Vega & built it like pro-Stock Bill Grumpy Jenkins. His wife drove it a lot with kids in car seats in the back seat. No, it was not tubed.

We cruised a lot even thou our cars on a good day got 10 mpg. If you were a car person. We would all congregate on the street outside of my high school. The majority of the cars except for one 1970’s era Corvette, were all late fifties to 1960’s cars. We would circle the school if you got there early. Can’t do that anymore. High School expanded & blocked off the street. I was in the marching band & made several car friends there. I was asked to help transport the garage bands of my friends. Roadie? lol, I could haul a complete drum set & the PA system in my 60 Impala to gigs around Toledo. I hated High School but, the extravehicular activities were the best only part. To go back to 1973 with what I know now? Back to the Future comes to mind.

A great article on a great movie.

One thing though — MLK was killed before RFK.

When Bobby delivered the shocking news of Dr. King’s murder to an Indianapolis crowd, it was one of the very few cities not to riot.

I still tear up over what might have been…

I don’t know which Roman came up with the phrase “annus horribilis” (horrible year), but 1968 must have been the sort of year he knew or imagined. As you suggest, the pain of losing Bobby and Martin is still fresh for many of us.

It’s a marvelous article about a marvelous movie. I graduated from high school in 1961, so it’s sometimes all too familiar a story for me. What I feel should be emphasized is the sheer scale of the talent deployed, of actors who were just emerging. The casting director should have gotten a Congressional medal of some sort. I do regret that Le Mat got lost in the tsunami of fame that followed.

I can still conjure up my adolescent fantasy of the man I wanted to be by murmuring “Bob Falfa.” I hope I’ve recovered, but I’ll never be sure.

This was the first no G movie I ever got to see. My Mother and Aunt took me to see it, We even went to a 50’s appropriate theater to see it.

What mom left out is the cars. I was already a car crazy kid but I wanted Johns coupe> Even older I still would like to build a copy of it or the California Kid as both are great representatives of the original concepts and not this over done billet stuff.

I later grew up and we lived our own nights in the 80’s with adventures of our own. We never pulled an axle out of a police car or drag anyone from the bumper but we did have some fun.

Years later I got to go to Hot August nights for work I was able to spend a few days with Bo Hopkins and Candy Clark. It was fun and we even has the real White T bird there with the same owners as who owned it in the movie. Sorry no blond was in the car,

Bo also was on Falcon Crest. He played a sorted person in that. An old lady came up and told him he was not a nice person in that show. He responded in his southern accent “Mam I was greatly miss understood”.

I really don’t thing the car movement would be what it was or is today had this movie not revived the practice. Today while the gang is getting older there are still gatherings on weekend of cars and racers. None of this cars and coffee stuff. Remember nothing good happens after midnight so they say.

How is building an exact copy of something that was just dolled up for a movie a great representative of an original concept? I will tell you where I was in ’62 – I was on the streets in hot rods, cruising and listening to rock and roll on an AM radio. And there weren’t any bright yellow Deuces out there that I saw!

Might not have been in your neighborhood but they were in others.

My point was that car was period correct and of the quality that some of the better cars were back then.

It is not like today where everything is billet and supercharged with AC and power everything in a fiberglass body,

If you dig back to the old hot rod magazines these guys did not paint all black or powder puff paint jobs. There were other colors back then and unfortunately often the black and white photos do not show the blues, reds and even yellows back then.

FYI one of the most fames Street Rod Racers was very Yellow back in the day. The Old Yeller cars build by Max Balchowsky are well know for not only their salt runs but road racing.

FYI I would not look too deep into the movie. Trying to change this into a social economic and political comment really kills what the movie was trying to relive. It was about good times and what kids faced in that day.

If anything it unintentionally shows us how far we have degraded as society and even in the car movement with the street take overs etc.

They tried to make the part two move more political and social speak and it failed as we live bad news everyday and movies are where we go to escape. That is why Star Wars, Harry Potter and other franchises all work as they give us a break to relive or enjoy good times and the good guy wins in the end.

This movie is classic for all all thoe I was only 6 years old a friend of mine lived next door and her older sister would dress like this and play this music that I would hear. As a little kid I can say that I was there

I could watch this movie every month. One of my top 5, ever. I graduated from high school in 1971 and was in college when this was released. I grew up in a small town in NW Georgia, draggin’ main street and making the circuit in my ’65 Impala SS. We don’t realize it until it’s gone, but my 4 high school years were the best of my life. It’s noted in the article, but without American Graffiti, there probably wouldn’t be any Star Wars.

The cars and the music make this movie so enjoyable.

Having grown up just 30 miles from Modesto in Stockton, CA the similarities were amazing. We had Pacific Ave, aka “The Av”, Modesto had J Street. When I first saw the movie in 1973, I was taken with the similarity of what I faced on my last night of high school. With three others I drove to San Francisco in my 56 Chevy, got home at sunrise and had to go to work. A stupid thing to do in retrospect because we had been drinking.

While in berween working at a newspaper and a gas station a couple of nights a week I cruised “The Av” until I got the letter from Greetings by LBJ. That of course changed my life and millions of others like me.

I am still a car guy, I went through five cars before I got drafted. A new 67 Cougar had to be sold and I still owed money on it. It took me until 2003 to replace that Cougar, even prettier than the first one. We live in the moment of daily life, our hopes still drift through our minds but our past never haunts us, rather it wafts through our memories in fondness of the times.

Now at better than 75 years of age, I have choices to make when I take out a classic car. Luckily, I have eight to choose from. A mild dilemma, but a good one. On Friday June 9, 2023 I will drive to Modesto for the Modesto Graffitti Week cruise on McHenry Boulevard. Another car from my Back to the future colection will be my ride, a 1956 Chevy Sports Sedan. AKA as a four door hardtop, which I had in high school and foolishly traded in for a 64 Red El Camino that was loud and fast! I now own another back to the future replacement, a 64 Chevelle Malibu SS, of course in red. We can replay the past if we write and act out the scripts for our personal entertainment and desires.

Thanks to George Lucas for this wonderful movie. I see Candy Clark at various car shows, especially at Peter Paulsen’s annual Hot Rod parties.

I was there! Along with George Lucas I was the infamous class of ’62 at Downey High in Modesto. Those few of us that actually knew George back then (through car activities) were surprised that he went on to college. None of us had appreciated the imagination that lurked within! But he really got it right! What really surprised us the most was to find out that we weren’t totally unique and that this “lifestyle” was so common to the rest of the country. What a wonderful film of a wonderful time!!!

Jim, Are you planning on goiing to the Graffitti cruise on Friday, 9 June? I hope yuou’re able to make it, with or without a car. I don’t know you, but you’re an original!