Media | Articles

The Special Life of a Very Special Car, Ch. I: Touring Europe in ’65

Some stories are too good and long to tell (or read) in just one installment, so here is the tale of this remarkable car’s three very different phases of life in my hands in three logical segments. You can find the first below. —GW

It was late and very dark on that chilly September night when I found the entrance to the Nürburgring’s front straight. The new German friends who had welcomed me to the ’Ring and shared their great German beer during (and well beyond) the day’s six-hour race had told me that, for a single deutsche mark, I could drive a lap of the track before it closed. As I recall, that was about 25¢.

As a just-out-of-school, 21-year-old, aspiring racecar driver in his brand-new 1966 Triumph TR4A, how could I resist that temptation? At the end of a long day of race-watching and partying, I was tired but (as far as I could tell) not drunk. Why not enjoy a lap or two of perhaps the world’s most challenging track?

As I waited in my red Triumph, I watched officials collecting money from a couple other cars. However, no one noticed me. I took off without paying. With no race training or experience, just high confidence and dim headlamps, I attacked that slow/fast, up/down, tricky/twisty, super-challenging track as I would any unfamiliar, hilly public two-lane—aggressively enough to explore the car’s agility but leaving margin for error, since I had no idea what to expect over each crest or around the next bend.

Mash the gas, squeeze the brakes, downshift, corner, exit, upshift through long, fast curves, tighter corners, swoopy esses, crest-topping yumps, a couple of tightly banked circles (one was the ‘Ring’s famed “Karussell”), and a long, long, flat-out straight heading back to the pits.

The TR4A had felt nimble and responsive on the road, and it further impressed on the track. With its engine upgraded from the 1965 TR4’s 100 hp to 104 hp and 132 lb-ft of torque, the car was not seriously fast but it accelerated eagerly through its slick four-speed manual. Steering was quick and responsive, the brakes strong and linear with no sign of fade, and its handling surprisingly good thanks partly to a set of Michelin radial tires. I encountered no other traffic and completed that 14.2-mile, 176-turn lap with a huge grin on my face and ready for another. Again, the officials didn’t notice me, and I took off for a second cost-free lap. Whoopee!

I negotiated that one intact as well, then was approached by an official on my return. Uh-oh. He explained in his best English that they were about to close the track but that I could do one more lap for one deutsche mark. I fished the coin out of my pocket, handed it over, and launched down the straight for a third thrilling lap.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

It was not entirely incident-free. Sailing down a fast hill, then braking for a left-hander, my foot slipped off the brake. Entering the curve too fast, the Triumph slid sideways into the right-side berm—thankfully not a guardrail or a drop-off. I felt a bump and heard a crunch as it scraped the dirt bank, then steered myself back on course. I was keenly aware that the car had no seat belts, so any crash would likely have pitched me out.

I was the last car out of the gate before officials swung it closed. Then I drove most of the night over the mountains on my way to Holland, where I intended to find and (if possible) drive the Zandvoort track, the site of Formula 1’s Dutch Grands Prix. When I later stopped under a light to check the car for damage, I found just a slight dent and scrape low on its rocker.

I never repaired that minor Nürburgring damage. I saw it as a badge of honor: three thrilling night laps of the ’Ring for the price of one.

Genesis

This big adventure was mostly my father’s fault. A farm kid from Nebraska who had raced hot rods on dirt in his youth, he sometimes took our family to a local quarter-mile asphalt track south of our Cleveland, Ohio, suburb, where we watched some fender-banging “stock” car racing. I instantly fell in love with it and wanted to race as soon as I was old enough and financially able. Much later, after getting my driver’s license at 16, I discovered another, better local track and got a weekend job there selling beer out of a little red wagon. I pulled it around yelling, “Cold beer here!” during breaks in the action, made $1.00 per case ($5.00–7.00 a night), and enjoyed a few myself. (You had to be 18 to legally sell beer in Ohio, but they never checked my ID.)

When my freshman-year college roommate introduced me to sports-car road racing at the (now long-gone) Meadowdale track north of Chicago—which featured a treacherously rough, steeply banked, 180-degree “Monza Wall” curve—that instantly changed my plan. I saw Augie Pabst and other brave shoes compete in thundering SCCA C-Modified (think early Can Am) machines and watched future famous factory driver Bob Tullius win the D-Production class in a Triumph TR4. After that, I studied up on SCCA (Sports Car Club of America) racing and decided that D-Production would make a good starting point once I was out of school. The class seemed fast enough to be fun but relatively safe and, most importantly, the eligible cars were semi-affordable.

In my senior year at Duke in 1965, while plotting which DP car to buy, I talked a dealer into letting me test drive the three most common models competing in that class: Triumph TR4, MGB, and Austin Healey 3000. The six-cylinder Healey had the most power but felt heavy and somewhat clumsy, and its low-slung body was known for dragging off its exhaust system. The MGB was lighter and more agile but a bit down on power. So, partially influenced by that Tullius win I saw at Meadowdale, I settled on the TR4. Its 100-hp 2138-cc four felt strong and torquey, and, crucially, its slightly flared fenders would allow wider tires under SCCA rules.

Heading for the Nürburgring

My dad, bless his kind soul, co-signed a loan for me to buy the Triumph following graduation and arranged for me to pick it up at the UK factory. My plan was to tour Europe in it for three weeks before starting work at Chevrolet Engineering in Warren, Michigan. As I recall, I paid about $2400 for a red U.S.-spec TR4A roadster—the new, updated model with ride-smoothing independent rear suspension based upon that of the Triumph 2000 sedan—with an optional heater and (new at the time) Michelin X radial tires but without available overdrive, wire wheels, radio, or seatbelts. Beyond seeing what I could of Western Europe, one key trip objective was to visit as many Formula 1 tracks as I could find. My dad had no clue that I planned to race the car.

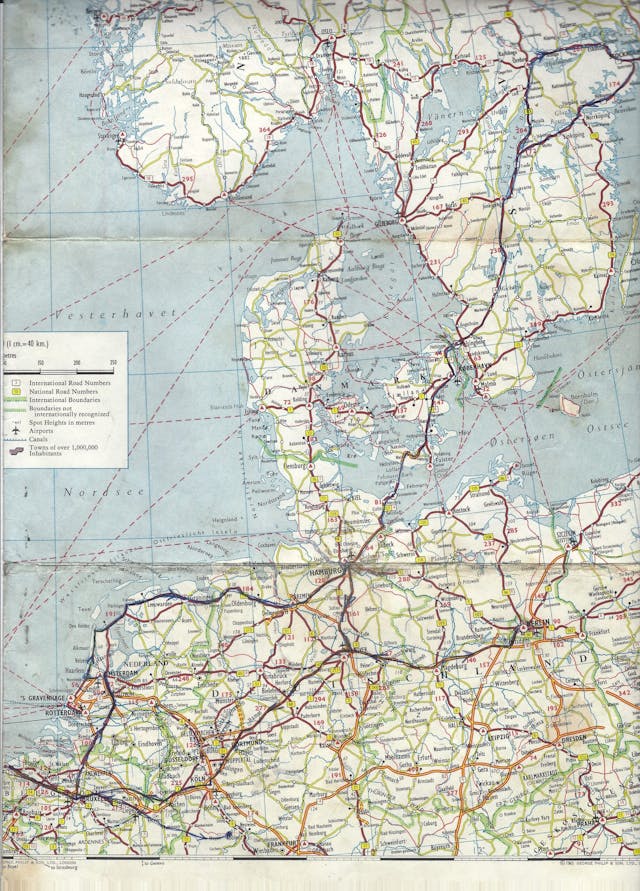

I took delivery at the plant near London on September 1, 1965, and headed to Dover to catch the ferry to Calais, France. It was my first time driving on the left side of the road; I had to constantly remind myself to stay left and drive clockwise around UK roundabouts. Once in France and back on the right side of the road, I aimed for Brussels, Belgium, on my way to Germany’s famed Nürburgring. I didn’t think to visit Le Mans, probably because it was not an F1 track. With very little traveling budget, I stayed in cheap (some free) youth “hostels” wherever I could.

Arriving at the ’Ring on a Sunday morning, I found that a six-hour FIA Group 1 race was about to start. So, I watched the start, which was done Le Mans–style, then settled on a convenient corner to take in the race. It wasn’t long before a group of friendly young Germans invited me to join them and share their excellent beer. After the race, they asked me to stick around for more partying at a local pub. I was planning to head for Amsterdam that night but couldn’t turn that invitation down. I played my guitar and entertained them with American folk songs, then, finally about to depart for the night’s trip, they informed me that I could drive the track for a small fee.

Hello, Woter!

I found Spa in Belgium but couldn’t lap it because it was mostly public roads. Only the pit-lane wall along the main highway revealed it as part of the famous F1 course. I spent a day and night in Amsterdam, a beautiful city with an eye-opening red-light district, where scantily clad women beckoned to passing tourists from apartment windows. I walked through the area and watched with interest but did not partake. The next day, I headed for Zandvoort.

Like the Nürburgring, that Dutch F1 track was open to anyone for a modest fee. Why did European racetracks do that? Probably to generate extra income between races by providing track-driving opportunities to European enthusiasts and, very importantly, because they didn’t have to deal with legal liability and avaricious lawyers as we did even then in the States. If you paid the fee to drive the track in your street or race car, you did so at your own risk. If you crashed your car and maybe injured yourself and/or others, too bad. Not the track officials’ problem. Lots of scary non-race crash videos from the Nürburgring show how often such unfortunate incidents still happen.

It was raining the day I drove Zandvoort. Since it was another challenging track, I was extra careful. My Michelins gave surprisingly good wet traction compared to the cheap bias-ply tires I had rolled on all my driving life. The only scary part was the one other car on course at the time: a very fast formula racer doing serious testing. I had to watch my mirrors constantly and be sure to make room every time he came around—at probably twice my speed.

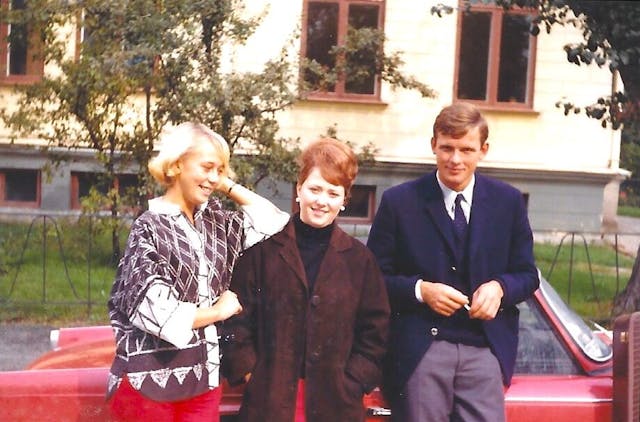

Nearly six decades later, I don’t recall where I headed from there. But the next thing that happened dramatically changed my memorable tour in the best possible way. I was having a tough time communicating in most places in France, Belgium, and Germany; few people were able or willing to speak English, and my second language was Spanish. Holland was the exception, and I soon learned why. Hoping for some English-speaking conversation and company, I picked up a young hitchhiker who I took to be either British or American. He turned out to be a Dutch medical student named Woter, who was returning home after a summer of mandatory military service on the Mediterranean. He told me that most educated Dutch were quadrilingual—fluent in French, German, and English in addition to their own language.

After some miles of driving and chatting, Woter asked whether he could travel with me for the next two weeks before he was due back in school. He seemed a very likable guy and good company, and his multi-language capability would come in handy. Sure, why not?

Denmark and Sweden

Woter suggested that we drive to Stockholm, Sweden, where he knew a woman friend. With little understanding of how far that really was (nearly 900 miles), I agreed. The good news: the route took us through much of Denmark and its beautiful Copenhagen capital, where I met a lovely college student and spent the night with her in her girls’ dorm room. She insisted that it would be no problem, and it wasn’t. But I was a tad uncomfortable in the shared shower the next morning. The arrangement seemed highly enlightened compared to the conservative values I grew up with in the States. I was liking enlightenment.

The bad news: Sweden, like the UK but unlike the rest of continental Europe, still drove on the left. (It changed to the right side two years later, in September, 1967.) So, I was back on the wrong side of the car on the wrong side of the road, and Woter became a very useful passenger as he leaned out of his right-side window to sight up the road and tell me when it was safe to pass a slower car on a two-lane highway. He even drove a bit when I needed a rest. He said he was an inexperienced driver, which made me nervous, but he did pretty well.

When we finally got to Stockholm, we met Woter’s lady friend and enjoyed a nice dinner with her and her friend, a sweet and lovely young Swede named Lena. But there was no alcohol consumption, due to Sweden’s extremely tough drunk-driving laws, and no hanky panky or overnight stay. The youth hostel down the street would have to do.

On to Berlin

I don’t recall whose idea it was or when we decided to risk it, but we headed next to Berlin, some 700 miles from Stockholm, which in those days was still surrounded by Communist East Germany and divided east/west by a heavily fortified wall. Twenty-four years before Reagan’s command to “Tear down this wall!” would be fulfilled, driving through oppressed East Germany to free West Berlin was a challenge that was definitely not recommended. But we were young and adventurous, and Woter spoke fluent German. What could go wrong? At least we would be back on the right side of the road once out of Sweden.

Well, we took a wrong exit off the autobahn while still in East Germany and immediately encountered uniformed guards with serious weapons. Woter patiently explained our mistake, the guards searched us and the car, then let us turn around and head back to the autobahn.

When we arrived at the border, we had to negotiate double checkpoints, one to exit East Germany, a second to enter West Berlin. At both were multiple long lines with no signs telling us which to stand in first, second, etc., but Woter’s German got us through fairly easily. Then first the East German, then the West Berlin, guards thoroughly searched our Triumph, even using mirrors to check underneath the car for people (or perhaps weapons).

Once safely inside the city, we explored a bit and took a good look at the famous wall that countless East Germans had attempted to cross, most of them quickly shot by guards in the towers that lined it. We did not hear of anyone ever trying to cross in the other direction. Then, after a restless night in a particularly barren youth hostel, we reversed the process, driving back through the double checkpoints and, eventually, out of East Germany.

Time was not our friend. We had just a couple days to get back to Calais, catch a ferry to Dover, and negotiate traffic to the London airport for me to catch my flight home. With just paper maps in various languages (no GPS those days), we faced some 600 miles of mostly two-lane driving, much of it through mountainous areas, to get to Calais. There would be no overnight stay and no time to explore any of England before I had to jump on the plane, and Woter would have to do his share of the driving while I caught brief rolling naps.

We made it … just barely. And I had to trust Woter, my new, inexperienced-driver Dutch friend whom I had known just a couple weeks, to drop me at the airport and get the Triumph (now back on the wrong side of UK roads) to its departure port for shipment to the States. Then he would have to hitchhike back across the Channel and to his school in the Netherlands.

I had his contact information, but if he didn’t deliver the car when and where it needed to be for whatever reason, how could I remotely track him down from back in the States and recover it? I did feel that I could trust him to get that done, but I worried about the car all the way home and for several more days until I got a letter from him and a notice from the shipping company that my now-well-broken-in new Triumph was on its way across the sea. Whew!

To read Chapter II, click here.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

“I was liking enlightenment.”

A fabulous arrangement of four words that, taken in the context of the story, conjured up a myriad of mental images that were, I hope, as must fun as the real thing. 😃

At nearly the same time (summer of 1964) I also toured a bit of Europe in a 1956 oval window VW Beetle, but my travels were much more constrained to mostly southwestern Deutschland (then called West Germany), Luxembourg, Northern France, and a few days in London. No racetrack visits, unfortunately, and that Bug wasn’t a beast well suited for the Autobahn. The biggest excitement came when I forgot to bring my passport one day when visiting Luxembourg City. No one even glanced at us as we left Germany, but when we tried to re-enter later the same day, the guards got real excited when I couldn’t produce any papers! Long story, but suffice to say that one never forgets what it’s like to be detained in a border station by guards packing Lugers until one’s passport is retrieved from the base and delivered to the authorities…

Oh, and I will verify that a Deutschmark in those days was indeed worth about 25¢ U.S. – which made calculating prices and the exchange rate really simple.

I enjoyed this article very much for several reasons, not the least of which is, I think, my fondness for the TR4. I’m quite jealous of the experiences Gary had in his!

Great piece, Gary, very much enjoyed all of it. Enjoy the holidays, and cheers! Ray

A terrific story by a talented veteran car writer. Sixty years from the date of his adventures, I salute his courage and trust in others.

As a 23 year old these days, I can’t begin to express my envy over these experiences

Very cool story. The Triumph was a good companion for this journey.

I had a “67 TR4A , which I loved and wish I still had. Although I loved the story, I wouldn’t have put my Triumph through all that traveling.

A brave and foolhardy adventure that I would love to have experienced. Good fortune was with you when meeting Woter who proved to be a trustworthy and fun loving guide and companion. Did you keep in touch with him?

I did keep in touch with Woter for a while but eventually lost touch as our lives moved on. I hope that he is still with us in his native Netherlands or somewhere and that this story about our memorable adventures together way back then somehow finds him. – Gary W

I had no idea you experienced such adventures! Fabulous storytelling — most of it (likely) true. Congrats!

All true and unembellished as I remember it, and I still remember it well.