Media | Articles

Joy of Six: A 400-mile awakening with an E-Type and the Blue Ridge Parkway

I read it in a book once: The Jaguar E-Type is magnificent.

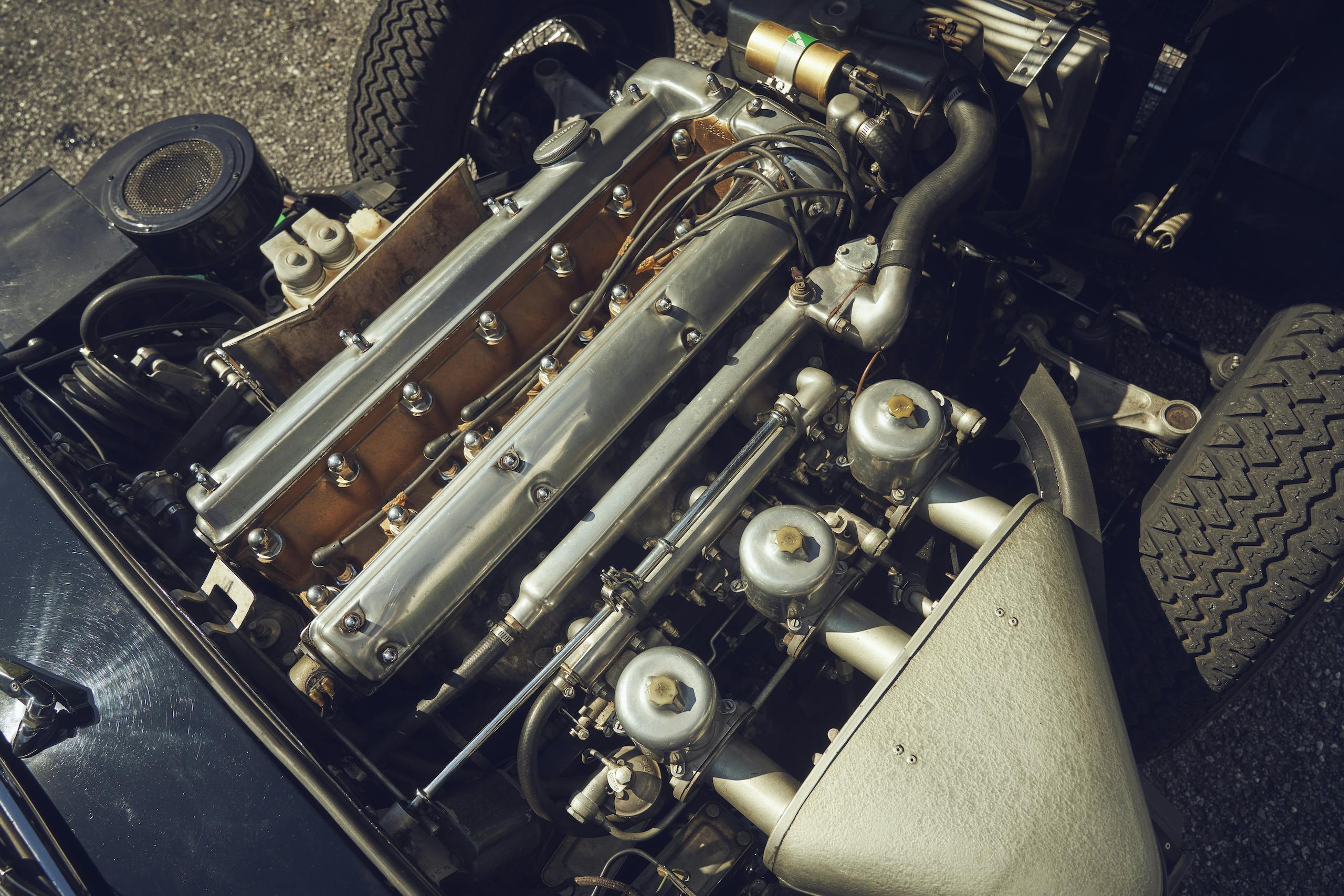

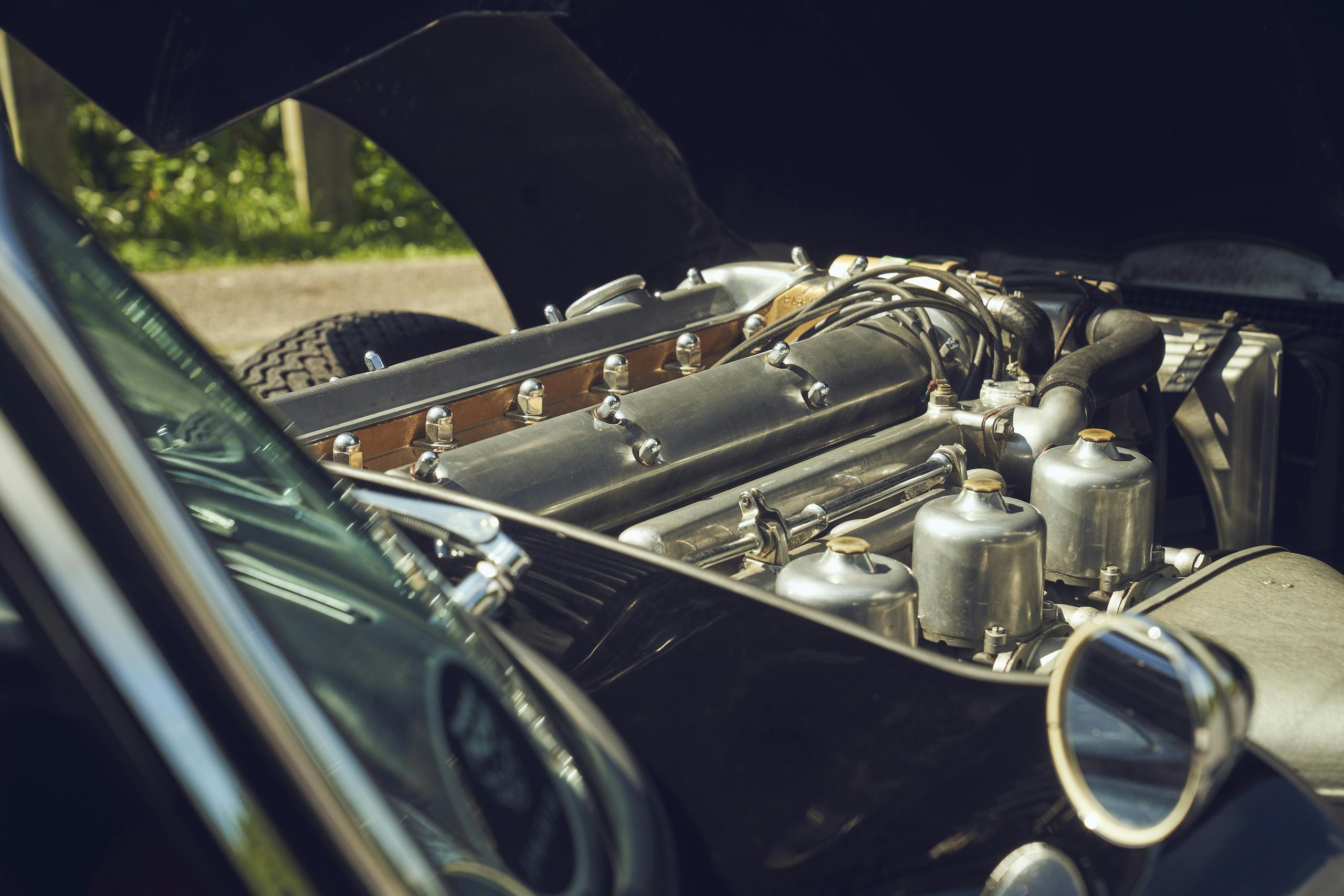

What a unit, that car. Launched in 1961. Body like liquid expletive. Six cylinders, two cams, a four-speed manual. Inboard rear discs and independent rear suspension at a time when most Ferraris still snorted around with a solid axle. E-Types were known for hitting a cool 150 mph in an era when most cars would clear 100 mph only if shot into space. They were built like the D-Types that won Jaguar Le Mans, a clever mix of tubular subframe and unibody. Books said that a drive would weaken your knees.

I read those books as a kid, 30 years ago. Before I thought they were all hooey.

Opinions are dangerous when rooted in reality. I grew up around a restoration shop. After college, I worked on European cars for a living, then sold Jaguar parts at a dealer in Chicago. By the age of 25, I had watched multiple men restore E-Types from bits. In school one summer, I helped a tech replace the clutch in a V-12 roadster, a two-day job iced with profanity. At the dealer, I burned lunch hours poring through factory manuals and microfiche, marveling at ship-in-a-bottle sub-assemblies; here was a machine of byzantine service notes, sustained only by frequent care and feeding. The rear suspension alone looked like a medieval torture device.

Logic said effort had to equal return. Why else would anyone put up with it?

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Then, still in my 20s, I met the hero. A friend bought an early 4.2-liter roadster. I climbed behind the wheel, owner in the passenger seat, and tore off down some tree-lined road. Ten minutes later, I sat at a stop sign for a moment and quietly wondered if I was having a stroke.

The owner elbowed me in the ribs.

“You love it, right?”

I lied and changed the subject.

Jobs at car magazines followed, as did other cars. There was the 100-point Series I coupe that seemed glass-fragile and slow as tectonic shift; the survivor 2+2 that stopped and turned like a 1970s Lincoln; the hot-rodded 4.2 roadster with some British tuner’s “fast comfort” suspension, neither fast nor comfy.

These were all quality cars, well-kept and so pretty. The best offered about as much of the fabled glory as an old refrigerator. Later, I track-tested a D-Type for work, yelling four-letter words at 100 mph, floored that the books could be so right with one piece of the rock and so wrong on another.

D-Types are seven-figure cars.

Wouldn’t it be great, I thought, if you could have that vibe without spending millions?

Lord, I was a doofus.

Not all icons earn celebration after their time. Drive an E-Type, people talk to you at stops. Generally along one of two themes:

1. Pretty car. What is it?

Or

2. Oof wow it is the legend in the flesh, how fast have you had it, my mother’s sister’s dog once dated a guy whose boyfriend ripped an E from Alaska to Texas in a single day hail England forever amen.

One week last summer, I met those conversations again. In Tennessee, at our trip’s beginning; in Virginia, at its end; and everywhere in between. People moth-flamed to our car at stops and overlooks, drawn wordlessly, staring for a moment before offering a belated hello, as if they had briefly forgotten how to talk.

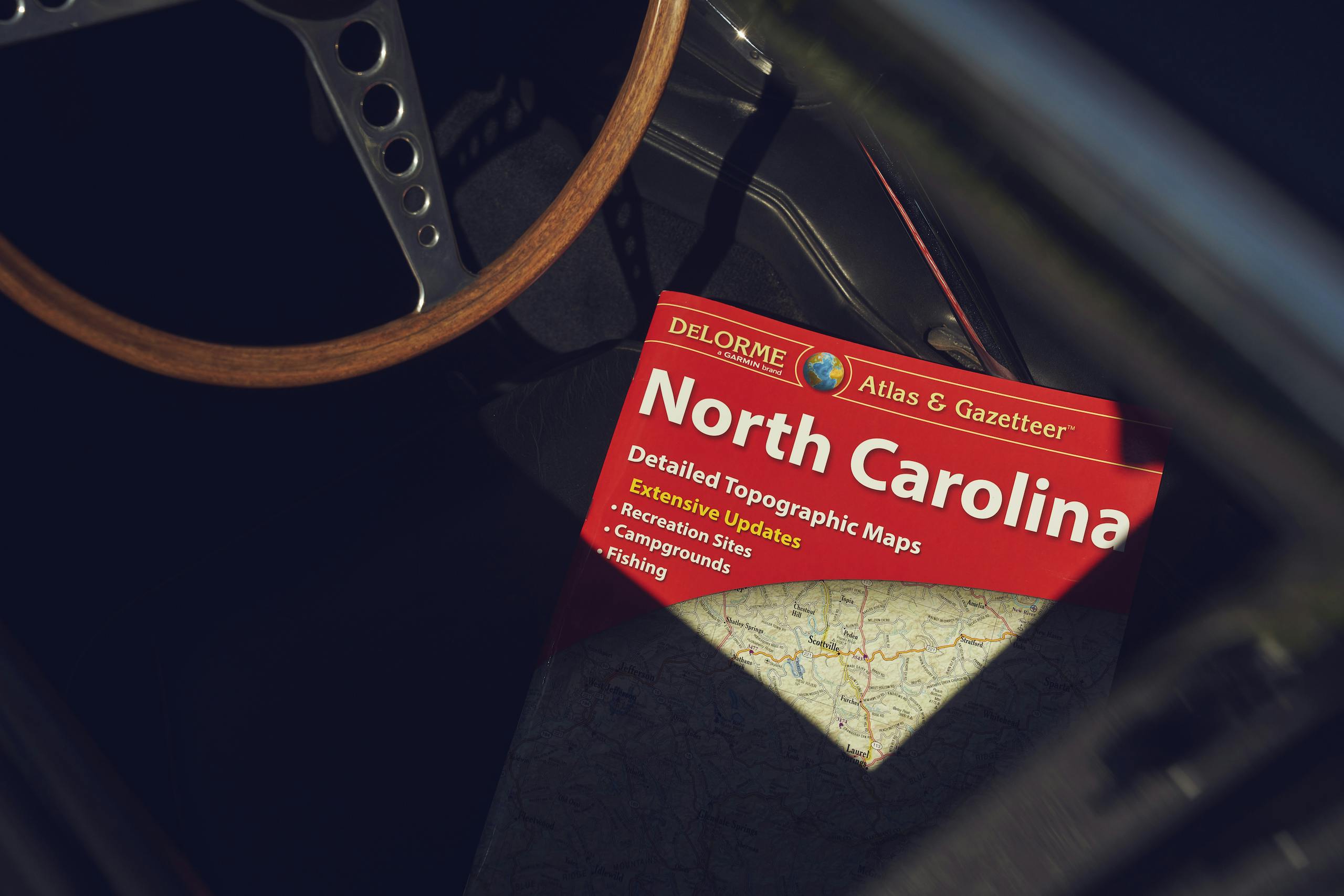

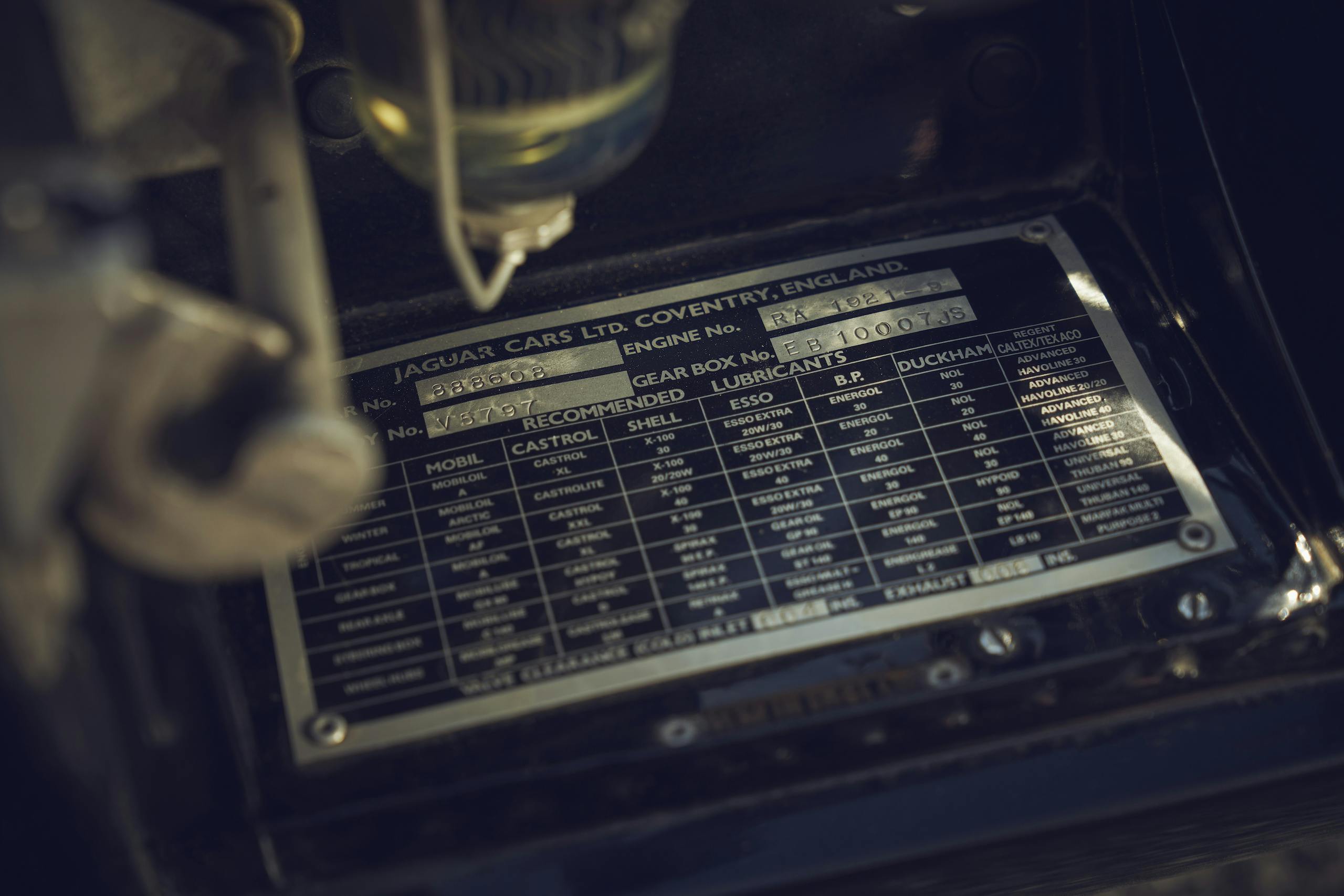

Most of those meetings took place on or near a 469-mile scenic parkway commissioned by the American government. They happened while standing next to a 1964 Jaguar E-Type Series I coupe, black, 3.8 liters, an aged but well-kept restoration. When I planned this drive, the parallel made me happy: The E-Type is a design icon, and the Blue Ridge Parkway was famously constructed as a public-works project under Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. One of these landmarks is a travel tool of staggering beauty, and the other is a road bridging North Carolina and Virginia via more than 200 overlooks and countless mountains. Beauty underpins the lore of each.

And oh, the car’s lore. Imagine the Jaguar factory in Coventry in 1961, picture its squat, nondescript buildings. At 7 o’clock on a winter evening, a freshly rebuilt E-Type coupe left, bound for Switzerland. The man at the wheel, a former racing driver and Jaguar PR man named Bob Berry, aimed for Dover, nearly 200 miles away, and the midnight ferry across the English Channel. Landing in a dark, rainy France in an age before blanket speed limits, he tore south. He got disoriented by fog in Reims, then upped his pace, making up for lost time—triple digits between corners, as fast as the car would go. At 11:40 the next morning, he pulled into the service drive of Geneva’s small Jaguar dealer. Attendants began cleaning the car before he had even climbed out. Minutes later, he was back on the road, headed to a nearby park, where Jaguar’s founder, Sir William Lyons, stood waiting to make an announcement. Some 200 journalists were present.

“Good God, Berry,” Lyons said. “I thought you weren’t going to get here.”

The E-Type was revealed. The crowd audibly gasped.

The numbers have long carried outsize weight. In the weeks before that trip, Berry’s mount hit 150 mph during testing. If you wanted a 150-mph road car in 1961 England, you could buy something like a Ferrari 250 GT—nearly £6000—or the £4700 Mercedes-Benz 300SL. The Jaguar cost £2100 and made speed like the Ferrari but was less fussy in traffic. The Mercedes was virtually faultless, but the bank draft for one 300SL would buy two E-Types and leave money in your pocket.

On top of this, the Jaguar looked like an E-Type: half airplane and half submarine, plus a healthy dose of lady bathing suit.

We left my house in Knoxville in early morning. The air was sticky and hot and the hills were fuming—trees shrouded by narrow towers of fog, the Smoky Mountains living up to the name. The Blue Ridge Parkway starts around 80 miles southeast of Knox, past a national park and thousands of acres of back roads. Sun bent through the fog, underlighting the forest.

I had figured the trip for a dawdle. The Parkway is mostly fourth-gear corners, sweeping and manicured, the posted limit never topping 45 mph. My friend Mark Hoyer drove the first stint, because the car was his. Mark is a volunteer firefighter from Southern California and the editor-in-chief of Cycle World. He is the sort of wry 50-year-old who says “rad” often and wears Adidas Sambas with shorts; he occasionally tours California on his 1954 Velocette MSS motorcycle; he once described a computer-controlled suspension as “Super Glidetron 7000.” Mark is also a walking encyclopedia on matters E-Type. On the road, I would ask him something simple, like how much choke one might offer an XK six-cylinder on cold start, and 45 minutes later, he would be wrapping up a detailed history of the Skinner’s Union carburetor, having briefly digressed into the recitation of a lightly profane rhyming couplet referencing how certain British cars look remarkably like a specific anatomical part of the human sexual experience.

You own a finicky old Jaguar with the wrong attitude, Mark once told me, you come dangerously close to having a bad time.

An hour in, after a long rip over coiled highway, we reached the Parkway gate. As the sun rose over the mountains, the land went purple, this graduated stair step of tone. At a photo stop, Mark offered me the wheel, and I took it.

The cockpit was tasteful and quiet, a drawing room of stretched animal, everything organic. Even the headliner was wool. The car seemed to move in long strides, the sort of sharp but yielding highway comfort that used to sell European cars, before they all grew too stiff. Machines long of footwell and gearing, happiest in big corners. Familiar stuff.

The dampers, though. And the cohesive whole, how the car felt in time with itself. Something was different.

I brushed it off. An E-Type, right? They’re all the same.

The engine hummed the quiet and busy little thrum of a machine with connecting rods as long as your forearm. Torque was everywhere, no lugging, just utterly flexible pull and a sense of telegraphing down to a distant boiler room when you wanted more. When you cracked the throttle, the car simply gathered itself and waterfalled thrust, no waiting. We climbed farther into the hills.

The E-Type was created by multiple people, but its shape sprung almost entirely from the mind of Malcolm Sayer. Jaguar chief engineer Bill Heynes once called him “the most charming man you could ever meet.” Sayer was also, as the saying goes, south of normal. He left university in 1938 with a degree in automotive engineering, then spent the war working on airplanes for Bristol. As an adult, he made furniture for his children from trash. He also drew odd cartoons, played the piano, built artificial plants, wrote silly poems, taught himself languages in days. He was married twice, having met his second wife atop a double-decker bus while still married to his first. One year after that second wedding, he moved his family to Baghdad to work for a university, then disappeared for six months.

When Sayer joined Jaguar in 1950, his first project was the body of Jaguar’s Le Mans effort, the C-Type. The following year, the car won the French classic overall. The D-Type that followed was an aerodynamic masterwork and visual ripsnort hailed by factory testers as one-hand stable at 190 mph. In an era when most designers focused on minimized drag, for pure speed, the man cared most about aerodynamic lift and crosswind stability, because they impacted how a car felt.

You read all that and think, Great, OK, makes sense: This bright and complex spark simply sketched up one of humanity’s slinkier thunderclaps through testicle and testament. Nope. The man styled cars through a sort of analog spreadsheet, a huge grid of calculated figures he called “body coordinates.” He would start with a rough drawing at full scale—the C-Type was laid out on a floor in chalk—then spend months on formulas and logarithms. The results helped shape a body buck, and boom, a Le Mans winner or a production prototype to curl your toes.

I always liked the bit about trash furniture.

North Carolina was a land of gifts. The first was a view to the horizon, the road diving gracefully into a small and tree-lined valley, no traffic. So I chose to hold the toothpick-rimmed wooden wheel with fingertips and flex my foot until that long throttle met the stop. On a curvy, lumping piece of pavement, from around 1400 rpm in second gear, the car snarled up to six grand. The sound began as a rushy sort of grumble and multifaceted stir, then mutated into a thick, back-throat snort, as if the muffler were behind a blanket. At the bottom of the hill, the car hit a bump midcorner at full compression and did precisely nothing. Just a whup and some impossibly velvet damping and we tore up out of the valley.

I looked down; somewhere in the middle of the whole exercise, I had grabbed third without thinking. We were glide-rushing up the hill in a deeply illegal form of extended-legs prowl. The wheel wiggled lightly in my hands.

“Mark?” I said, cautiously.

“Yeah?”

“This car is not like … the others? You know?”

“Yeah?” He watched the trees for a moment, unsurprised. “Well, cool.”

He told me about the rear shocks later. New-old-stock Girlings, older than me, four of them at the rear axle, as an E-Type had from the factory. They were part of the equation but not the whole—and more important, Mark quietly admitted, not cheap, perhaps more than most sane folks would pay for mummified car parts.

This was, as I learned, indicative of Mark’s obsessively chill approach to maintenance—things as they were, plus long thought in the details. His car had been restored 30,000 miles prior by a man named Ray in California, at a shop called “Dr. Jaguar.” Mark had handled all 30,000 miles and much of the service himself. There was apparently much learning and tweaking and question-asking of metal-cat physicians.

“You know,” he said, somewhere in upper North Carolina, “you develop a support network, owning one of these. People who know how the cars are supposed to be, because you can’t just screw them together and expect them to automatically feel right. Hell, some of them didn’t drive right from the factory, subframes cross-threaded and tweaked, that sort of thing. There are good ones and bad ones, and it has nothing to do with money.”

“No money,” I said. “Check.”

“My support network is Ray. I was talking to him when I bought my Jaguar Mark II”—picture a four-door, live-axle E-Type—“saying, you know, it’s nice, the car has this adjustable steering column. And he was like, Well. It turns out there’s this thin piece of cardboard in there, like a greeting card, the insulator between hot and ground. And so you move the column a bunch, it wears through, and one day you have smoke coming out of your steering column and you don’t know why.”

I was reminded of the older man, in his 70s, who came into my Jaguar dealer almost 20 years ago. His XJ was in the shop every month for something. Once, a tech and I politely asked him: Why not find another car, or even a Jag that didn’t need work every four weeks?

“Well,” he said. “I love this one. You’ve been in love, right?”

A wink. Then he wandered off to wait in the customer lounge while his dashboard was reassembled for the third time that year.

Clouds drifted across the road. It began to rain, fitfully, and then the Parkway rose above the weather, over valleys carpeted with clouds, past spotty patches of wildflowers.

“I did 130 mph in this car once,” Mark said, unprompted, chuckling. “There was more. But I lost … interest.”

As a kid, I spent a long time thinking that great inventions are only ever created or appreciated by people with a sense of humor. Turns out that isn’t how the world works, except when it does.

The rain picked up. There was no traffic, so we did not slow. I looked in the mirror and saw the mountains forming a bowl behind us, maybe 50 miles wide.

They did airflow tests with tufts of wool. Little 4-inch bits of sheep taped onto the bodywork. Sayer would ride in a car alongside, watching the wool move. He also rented a wind tunnel, mostly at night, when nearby villages were asleep and the tunnel could draw enough electricity for max pressure. But he preferred the road for research. Shortly before Geneva, Jaguar invited English magazines The Autocar and The Motor out to drive a prototype E-Type at 150 mph. Top-speed testing had begun months before, on a proving ground, then moved to public highways.

“Very often we would be doing 150,” Jaguar’s chief test driver, Norman Dewis, once said, “and other [test] cars were there as well … high speeds, Aston Martin and other firms.” Years later, in England, Dewis told me that he would drive one-handed at 150 and wave at other factory drivers. He found this funny, but then, when we spoke, he was holding a glass of gin.

“If [drag] were the only problem,” Sayer once said, “it would be very easy. But … stable … this is much more difficult.”

The E-Type is one of just nine cars to have entered the permanent collection at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Under “artists,” the exhibition lists three men: Sir William Lyons, Malcolm Sayer, and William M. Heynes.

The road continued. Hours, days, that magnificent scenery becoming almost rote until we reached a part of Virginia lower and less spectacular. Honeysuckle dotted the shoulder for miles. Traffic remained oddly absent.

Sayer laid out the roadster, but the E-Type coupe—arguably a more resolved shape—was someone else. A Jaguar stylist named Bob Blake tacked 3/16-inch steel rods onto a roadster one day, playing with form. Then Lyons walked in.

“He put his hand to his mouth,” Blake said, “the way he did … just walked round and round … said to me, ‘Did you do this, Blake?’”

Yes, Blake told him.

“He said, ‘It’s good. We’ll make that.’”

In person, the shape resembles frozen ballet. Possibly a self-fulfilling perception, because the car feels balletic at speed, its reactions suggesting measured choice. Like anything with soft springs and thin tires, an E-Type wants slow hands; you can almost feel the wheels compress as the car ramps into load. The steering is similar at 25 mph and 100, never too talkative, just a subtle nudge for attention. And little wiggles of kickback on bumps, so you know.

Twenty-five-hundred rpm in fourth was 65 mph.

Warmed, the engine started on half a crank every time.

We reached the end of the road. Not the real end, but a detour. A construction zone had closed the road maybe 100 miles early. We took the highway north, attempted to re-enter near Charlottesville and finish the road backward. Only the entrance there was socked through with fog, visibility down to a few feet. So we headed home.

The Parkway by then felt like anachronism, this fluid thing apart from the world, where driving works as it does in your dreams. Which was odd, because the car itself had somehow mutated, when I wasn’t looking, into a machine entirely free of excuses and every bit the lore, both separate from normal life and wholly capable of dropping into modern traffic without complaint.

On a nearby interstate, I briefly allowed the Jaguar to cruise natural. In the meat of the tach in fourth gear, there was so little wind noise, you could hear the window cranks turn. I became lightly aware of a quietly blooming desire to never drive anything else.

The last E-Type was built in 1974. Few that remain see regular sunshine or public eyes, and fewer still spend their days crossing France at a buck-forty. Which means that our faith in the legend has to do most of the legwork of keeping the thing alive.

A tall order. You love an object from afar for long enough, the gap between story and reality can sting. Or maybe, after countless tries, you get lucky. The stars align, a familiar tale gets retold in a familiar place, and you remember that faith often goes a long way. As does the realization that you were once too young, and possessed of too many facts, to believe in something so happy and perfect as the truth.