Media | Articles

In Tennessee’s misty mountains, we simplify and add three Lotuses

This article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe and join the club.

There was once a car company. Perhaps occasionally more of a ramshackle collective. One man built and sold automobiles to finance his racing, and along the way, his little team reached Formula 1, and their thinking was so relentlessly innovative that it managed to systematically permeate and rebuild an entire sport.

The man’s cars were special. Often unusually constructed and bleeding-edge advanced, but also temperamental and fragile. Critically, they usually carried some spark of madness that sucked people in.

This template is the story of a dozen English carmakers born in the years immediately following World War II. Primarily, however, it is the story of Lotus, one of just a few of those shops left. And because it is the story of Lotus, it is the story of the Lotus founder, Colin Chapman. A man who led his firm to both an Indy 500 win and 13 F1 titles. Whose infamous obsession with low mass and relentless progress meant that his sports cars were often transcendent to drive and his race cars often winners, except when they broke, or when they merely fell apart under something like the strain of their own weight.

Lots Of Trouble, Usually Serious, as the joke went.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

“Simplify, and add lightness,” Chapman once said, virtually a company motto. Pull tubes from the frame until it collapses, the apocryphal quote goes, then put the last one back.

Keith Duckworth, cofounder of F1 engine mavens Cosworth, said of Chapman, “He wasn’t a detail designer… [but] the most brilliant conceptual engineer I’ve known.”

Former Lotus engineer Ron Hickman: “He was a magpie.”

Former Lotus sales chief Graham Arnold: “Totally uninterested in a car five minutes after it [was] launched… a great man for proving something could be done, but that was that.”

Finally, Mario Andretti, Lotus F1 world champion: “Colin routinely told me… ‘Your next car will make this one look like a London bus.’ And he was right. That was the beauty of Colin. If you rode with him through the peaks and troughs, he’d always deliver. Of course, there were plenty of troughs—but he could make you a champion.”

Some forms of genius are divorced from stability. Founded in 1948, Lotus has had a long list of owners. First, Chapman himself. Then, after his 1982 death, General Motors. Then Malaysian carmaker Proton. Since 2017, the brand has been the property of Chinese carmaker Geely. Every prior owner struggled with keeping the place funded, not least because featherweight sports cars do not sell like hotcakes.

Car companies are basically living ideas, and ideas stay alive only as long as someone believes in them. Take the Seven, the first profitable Lotus road car. In 1973, after 16 years of production, Chapman whipped off and sold the design rights to a car dealer in the English town of Caterham. Possibly because he was over it. Ever since, Caterham Cars has annually built and sold Sevens by the hundreds, regularly updating the car through near-endless cosmetic and technical variation but no full redesign. Even now, orders are waitlisted for months, the factory at capacity.

Consider, too, the Lotus Elise, a mid-engine, fiberglass-bodied dervish launched in 1995 during one of the marque’s many fallow periods. The model was once the company’s only production car, but its platform was later tweaked into two variants: the track-weapon Exige, nearly an Elise twin, and the Evora, a larger GT car. Like the Seven, those three machines were consistently updated but never fully redesigned, the Elise’s bones helping keep the house afloat through 25 years and some 51,000 sales.

The Elise platform is now dead, finally canceled last year. Its replacement, the Emira, weighs around a thousand pounds more. That car will be joined by a new electric hypercar, the Evija, and an electric SUV, the Eletre.

These are upmarket moves, a brand rethink aimed at higher margins, greater volume, and the booming luxury sector. Chapman famously tried to take his company upmarket and failed, unable to find the right mix of philosophy and business. Moreover, the badge he created has only ever been applied to gasoline machines, and at that, never more than 1800 road cars annually. (Context: Ferrari sells five times that each year.)

Critically, the brand appears to be minimizing one of its founding tenets: lightness. The first Elise weighed around 1600 pounds; most Sevens clock around 1200. The Evora, the heaviest Lotus in history, hovered above 3000. That new hypercar is said to weigh more than 3700 pounds, and the Eletre is rumored to exceed 2 tons.

Chapman loved low mass in cars because it generally means focus and ability. The modern production automobile is heavy through a certain amount of practical necessity, not least for safety and comfort. Those new weight figures are not standouts in their class, or even particularly impressive.

To rethink anything, you have to chew on your definition of need. The question here has nothing to do with electric power or tradition and everything to do with the fact that it is difficult to be your best when you abandon who you have always been.

***

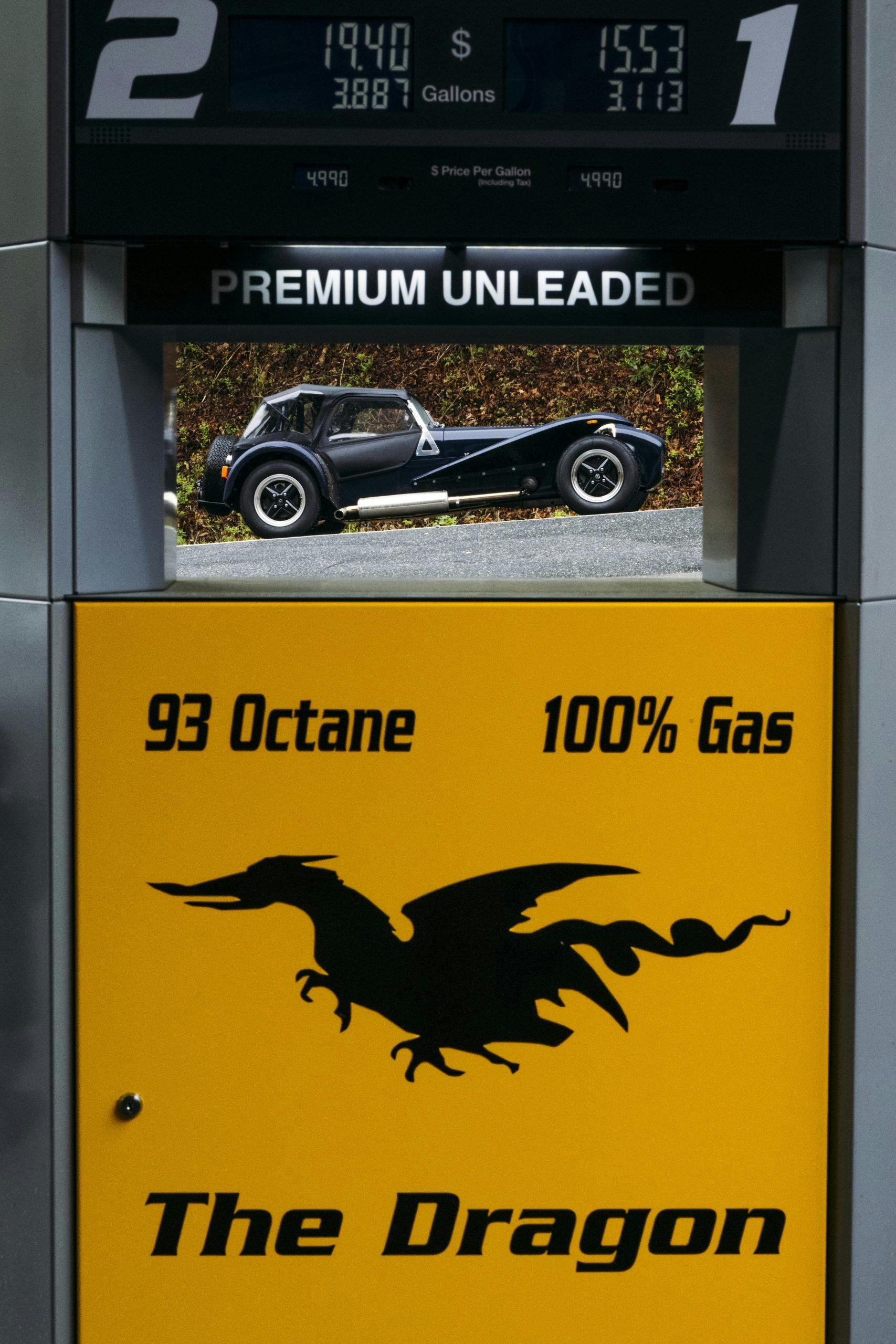

We brought three British cars to Tennessee’s Smoky Mountains, a place that looks nothing like England save occasional rain and fog. There was a 2020 Caterham Super Seven 1600, a 135-hp car weighing 1246 pounds with a De Dion axle and a modern, fuel-injected Ford Sigma four. This is essentially a Ford Focus engine and has been the motor of choice for factory Sevens for decades. “Factory” being relative—Caterham sells turn-key Sevens in many markets, though U.S. law means we get the model only in kit form.

Two years ago, when brain cancer began to kill my mother, my father sat by her hospital bed for days. For whatever reason, the blue Seven on these pages was one of the last things they discussed. Shortly after, my father, a dyed-in-the-wool sports car person then 66 years old, took a deep breath and laid out $48,030 for a stack of crates freighted from England. Mom is gone now, but the car is here, and he built it, and that process helped him get through her passing. Not for nothing is his Seven the same color as the Volvo 240 that she drove and loved when her kids were little.

Hagerty friend Jeff Lane brought his Seven in from Nashville. His 1981 Caterham looks vaguely like Dad’s car, if shorter and more narrow and ultimately simpler. It comes from relatively early in Caterham’s run and is thus closer to the Lotus original. It’s carbureted, with a live axle, like all Lotus Sevens. The interior is mostly bare aluminum and seats. In traditional Lotus fashion, many of the ancillaries in both cars, from the turn signals to the four- (Lane) and five-speed (Dad) gearboxes, were originally designed for other carmakers and borrowed to help minimize R&D.

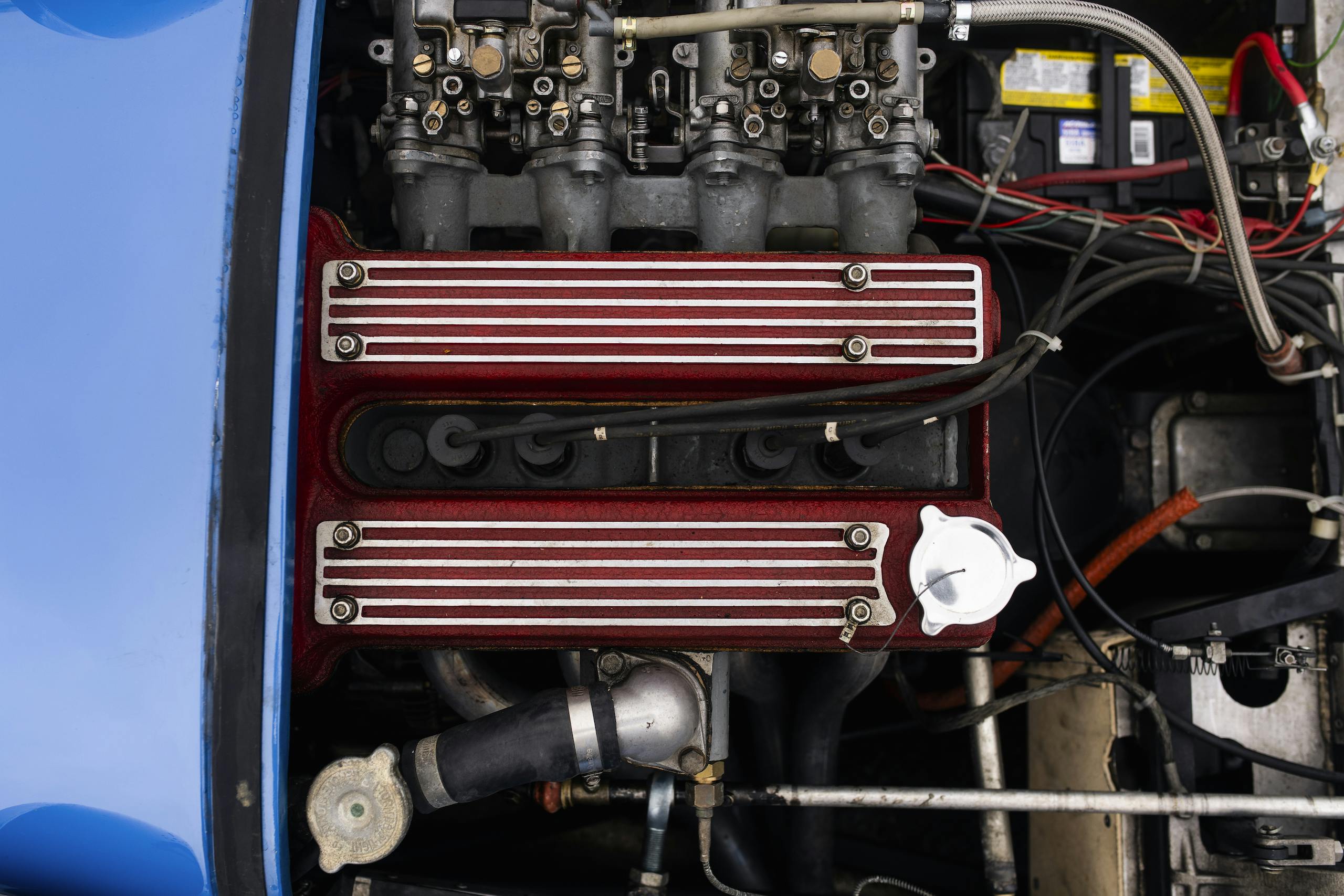

The tube frame underneath those aluminum and fiberglass panels is heavy on midcentury racing car. Imagine a Formula Ford stretched and poked a little. Lane’s 1.6-liter Lotus-Ford twin-cam four makes 125 horsepower; Chapman had the engine commissioned for another benchmark, the first Lotus Elan. It is rippy and excellent, with killer torque. If you smell fuel, that means the sidedraft Dell’Ortos are using it.

One miracle of a good Lotus is how the cars combine sharp handling with remarkable compliance and comfort. The car just wraps itself up into a place where you just know, telegraphed into your bones, what the tires want. Need a smidge more load on the right rear? Nudge a pedal or the wheel, and the change is made, and you know that, too.

The driver’s left elbow flirts with pavement. All while you are lightly tucked and folded into a cockpit so tight, it might as well be a coffin.

The tuning philosophy is dated but special: moderate suspension travel plus substantial spring rate and a sense of dance-fighting with pavement. Excessive grip means real speed comes easy, and a Seven feels like it turns from somewhere close to your knees. Road driving is generally either an undramatic point-and-shoot at what feels like reasonable speed (but is, in fact, slightly over the posted limit) or whip-cracking the car into a bright-eyed mania while certainly not doubling that limit. The caveat, of course, being that a Seven gushes sensation overload and confidence at any speed, so you err toward max attack.

I owned a Seven once. When I bought the car, it was after two years of searching for the right one. Most of the examples I looked at had either 500 miles on the clock or a million. You either love this stuff or want out now, apparently.

In Tennessee, we spent a day and a half in those mountains, barking across counties in the rain. On the second day, when the sun came out and the hills lit green, driving felt like flying.

The two cars exhibited practical difference, evidence of Caterham’s long work on the design. Jeff’s exhaust made me left-ear deaf, but the cockpit was relatively calm. Dad’s car was quieter inside but gave enough wind blast for near-instant tinnitus, byproduct of a longer and roomier cockpit. A Caterham change from around 40 years ago, it involved pulling the seats farther back from that barn door of a windshield and lengthening the wheelbase for stability at speed.

The earlier car has more wheel kickback and bump steer. Its front suspension is simpler but less effective, with the antiroll bar also serving as the front half of each upper A-arm. Rough pavement is light drama in any Seven but less so in the new one, where wheel control is noticeably better. Each Cat’s unpowered steering rack gives the low feedback common to purebred race cars, talking mostly to fingertips. It doesn’t matter—you feel more than enough through the seat.

Below 70 mph, before aerodynamic drag blooms, every Seven is quick. For decades, even a 100-horse example could run down supercars on back roads. As a bonus, early Sevens were affordable. Then supercars got even faster, and Caterham’s prices went up, and the point clarified: The immediacy and romance were the true drugs, how the car made the rest of the world feel cold and asleep.

Tree reflections splash over the headlight bowls and fenders. The view is hypnotic, dragging your eyes off the road.

If imitation is flattery, the Seven has long been flattered. There are now books to help you build your own from scratch, whole online communities. All it takes is some light blacksmithing and an obsession with less being more. I have tested home-built Sevens crafted from Toyota axles or Miata suspensions, with BMW engines and frames largely sourced at Home Depot. Those cars ran the gamut from great to trash, and quality was never the point.

“There are 10 solutions to every problem,” Chapman once said, “and you should never be satisfied with the first one. You work them all out, then find one that has particular merit in terms of simplicity, elegance, cost, refinement. When you’ve wrung it to death and can say, ‘That’s the essence’—then you build it.”

What we have here, then, is both a philosophy and a sense of raw possibility. It’s the same thread found in early California hot-rodding, balanced as only a magpie Brit once knew how. An old combo, but as relevant as the day it was born.

***

The final third of this story was supposed to be a lightly enthusiastic look at the first-generation Lotus Elise. We brought one with. Jeff Lane has a 118-hp 1998 example. The model was built from 1995 to 2000 and never sold legally in America, but Lane runs a car museum, and that building has held a Series 1 Elise for years.

The Elise is not a car for everyone. It is also possibly extremely very much for me, me alone. I need one, and maybe you do too, but also possibly you don’t, it’s very much a binary condition and you only know from behind the wheel. I could talk about this imperfect but also sublime car for pages and pages or days and weeks.

Your narrator is a near nobody in this world, a car-magazine writer, a former professional mechanic of no distinction, an amateur road racer of only light repute. I have, however, tried more than a dozen Sevens, Lotus and otherwise, and I know a few things. Chiefly that these cars are at heart basic tools, a mainlining of speed and involvement under a hat of old-world lore.

An early Elise is something else entirely.

We do not have room here for the backstory, which is a shame, because it is entertaining and basically a series of gambles, like any good yarn of engineering. The car was named for the daughter of a period Lotus backer, Romano Artioli, the man who revived Bugatti in the 1990s. The tub is formed of bonded aluminum, back then a lightly revolutionary choice. Lotus was hurting after years of slow-selling cars, and it needed a next step.

The company got that step, and so did we— America also saw an Elise, though not this one. Our car, the Series 2, arrived in 2005. Around 400 pounds heavier than an S1, it was still remarkably light, and yet the S1 is gossamer by comparison. The latter is heavier than any Seven but feels ethereal in how it bats around and carries itself. Ballet versus kickboxing.

The sum is deceptively simple. As in the Seven, you wear the car like pants, threading legs in between sill and center tunnel. The windshield is a long waterfall over a plain plastic dash, so wide that the world appears to fishbowl through it at speed. Interior bits feel cheaper than you expect, but then, that has been the Lotus Way since Chapman, for better or worse.

The Elise points a hair less sharply than a Seven, but it moves with more music, brakes with less immediacy but the same telepathic pedal, rides more softly. This is a calmer car, more adult. The suspension’s soft knees belie substantial grip. Shifting means holding the knob like a raw egg, placing it purposely in that vague and sloppy pattern, or the five-speed gearbox balks. The cable-operated linkage forces a delicate hand. Period journalists famously hated it.

For some of us, though—and he said this tentatively, to perhaps not sound insane—it is merely like Zen? Easy and calming, if you care to get it right.

Many Sevens have no room or need for a shift linkage; the car is small enough that the lever is often directly moving gearbox internals. Nor is the engine in a Seven a nonevent, inches away and uninsulated. By contrast, the Elise’s quiet little mill is a defining nothingburger, a 1.8-liter twin-cam Rover four that you hear only occasionally and feel even less. It sounds like a slightly rough Honda, with a cammy pull up top. But it also feels so distant and reserved that you focus wholly on the chassis. The steering never ramps into a blast of feedback—nothing here is a shout—but the wheel does offer subtle chatter from the first rolling feet. Then more and more after that.

Perhaps none of that reads worth the trouble? As if you’d drive it and think: Hey, Jerkface, what’s so special here? Isn’t this just a tiny box of glue and aluminum?

Except on the right road, in the right air and weather and phase of the moon, the Elise feels organic and lovely and infinitely defensible. Like a lot of old Lotuses, it rings hollow in the best of ways, so wispy that you wonder if the car is towing bits of its personality behind in the breeze, like a kite. A Seven is a rock by comparison, half the compliance and twice as stiff. The American-market Elise, the S2, was the same idea plus more aggro, wider and fatter. Those cars were great, but they were also, astonishingly, not the same thing, despite being so close.

The difference makes you think about legacy. How a brand is not merely a name or logo but a way of thinking, needing bulwark against counterproductive change. That’s what Chapman got right: the idea that you should do you, undiluted. And then other smart people took his ideas and ran with them.

I write all this stuff down in a notebook and I get clichéd Robert Frost thoughts, wondering where we diverged in the wood. How a focus on low mass can be intimately connected to feedback, or durability, or tire wear, or efficiency, and yet also be virtually abandoned by an entire industry. Or perhaps how the existence of that divergence is proof that we all had a choice, collectively, and that most of us decided minimalism wasn’t really the path.

Which is fine, of course, because some paths aren’t for everyone. Nor can they always support the weight of a business. But we happy few, right? Brains flapping in the breeze in cars that eject you from reality for a minute and get worn like a pair of pants. We do not know where Lotus will go in the future or how to make a modern car company withstand time and market. We like the new and different and do not hate progress, but we will also not go gently into that fat and lumbering good night. And we will be better for it.

Join us.

***

2020 Caterham Super Seven 1600

Engine: 1.6-liter I-4

Power: 135 hp @ 7000 rpm

Torque: 124 lb-ft @ 5600 rpm

Weight: 1246 lb

Power-to-weight: 9.2 lb/hp

0-60 mph: 5.0 sec

Top speed: 122 mph

Price when new: $48,030

***

1998 Lotus Elise

Engine: 1.8-liter I-4

Power: 118 hp @ 5500 rpm

Torque: 122 lb-ft @ 3000 rpm

Weight: 1612 lb

Power-to-weight: 13.6 lb/hp

0-60 mph: 6.1 sec

Top speed: 126 mph

Price when new: £18,950 (~$29,560)

***

1981 Caterham Super Seven

Engine: 1.6-liter I-4

Power: 125 hp

Torque: n/a

Weight: 1300 lb

Power-to-weight: 10.4 lb/hp

0-60 mph: n/a

Top speed: 110 mph

Price when new: £5000 (est. ~$9500)

***

This article first appeared in Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Click here to subscribe and join the club.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

“…some spark of madness–some dopamine faucet of speed and balance–that sucked people in.”

Our of my great respect for your body of work, I promise not to send that nugget to the “Block That Metaphor” desk at the “New Yorker.”

OTOH, “towing bits of its personality . . . etc.,” is pretty nifty.

Actually Elise was the name of Romano Artioli’s granddaughter.

Her name is Elisa Artioli. She is active on social media and seems pretty cool. She goes by iamlotuselise on Instagram.

In the second picture on the Camden Thrasher, I had to look a couple of times to figure out the picture with the face in the rearview mirror behind the headlight. It looked like he had on the world’s coolest little helmet.

The title of the article is wrong. According to the company itself the plural of Lotus is…………Lotus.

Hullo Rick, good point, but in my younger years in the UK we used to refer to a colection of them as”Loti”.

Cheers

Richard

Lotus is dead. Whatever fat-larded up SUV’s and overweight battery coupes coming are not the Lotus way. Add lightness not weight. What you drove is a Lotus. The future is overweight.

We are fortunate to race a ’72 Alfa GTV in SVRA and VSCDA. Another competitor is John Nash in his ’62 Lotus Seven. It is a blast to watch him race…he rarely loses! I’ve never been sure if it’s the car or the driver that is so exceptional. Obviously, it’s both!

I wonder what Chapman would have been up to today if he hadn’t taken that big heart attack at 54? He probably would have been in jail for about 7-10 years over the stolen/fraud money from the De Lorean fallout, and then he would have been back….I guess?

test comment

Thank you, Sam Smith, for your Ode on an English Urn.

Minimalist philosophy indeed from Mssr. Chapman, with all his faults and genius.

Heading out now for a back road tour in my ’66 Super Seven, thanks to your clever prose…

Superb photography by Mr Camden Thrasher as well, I must say.

Captures the peculiar mist of the Smokies, and the unexpected bursts of sunshine that can greet you at the summits.

The Elise S2, engineered for the US market, suffers from “US disease”, where if a little is good, more must be better and too much is just enough.

Uncalled for fatter wheels and tires add weight where is is unnecessary. Just look at all the ridiculous vehicles in the US that have outrageous over size wheels and stupidly low profile tires. Even Range Rovers with 24″ wheels and ‘no profile’ tires that look ridiculous and sabotage the smooth riding OEM setup. Clearly many US vehicle owners are completely without gorm.

Lotus never exceeded the original Elans and Plus 2 coupes……

I’m reading this over again after living with a 1995 Caterham with — this stuff matters in a Caterham — a Lotus Big Valve twincam, 4-speed Cortina gearbox, and ‘Italia’ live rear axle they put in them in 1995 if one specced a live axle. The 7 is indeed a bit of a brute in terms of handling, all elbows if you will. The twincam makes such a joyful noise. But I think I need to seek out an early Elise. It sounds like driving a dragonfly.