Media | Articles

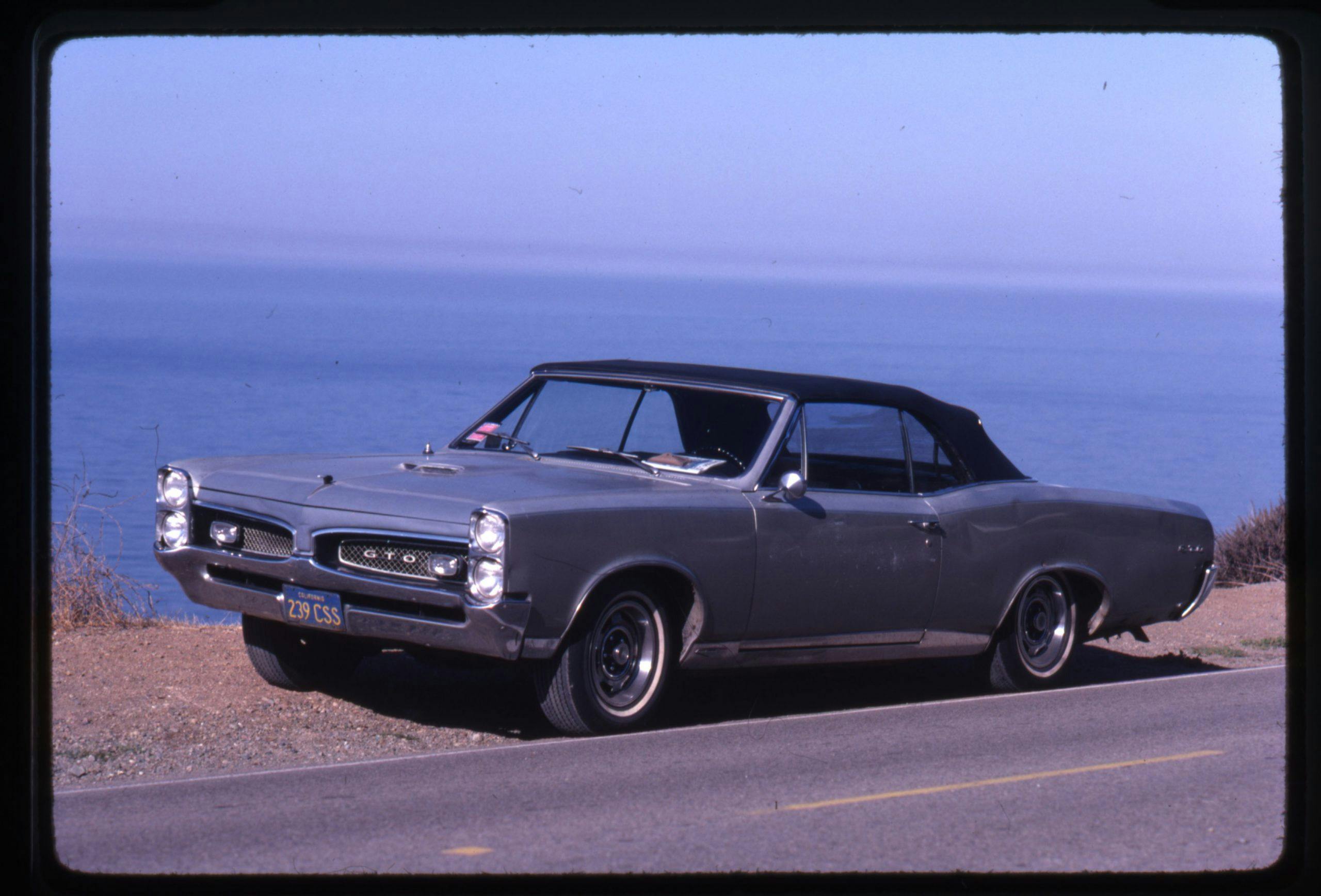

Reunited with my GTO after 40 years, I began the 2000-mile drive home

On a moody fall Saturday, the last bit of sunlight flitted between Rocky Mountain peaks, flashed across the glacial valley and through thick aspens crowding the Trans-Canada Highway, and exploded through the water-streaked windshield right into my retinas. Kaleidoscopically orange, green, white, black—the sunset was backed by the primal 3000-rpm beat of the 1967 Pontiac GTO’s 400-cubic-inch V-8. The wipers added no rhythm though, because, naturally, they were broken. Instead, the afternoon showers, dispersed by Rain-X, formed rivulets that wobbled up the windshield to gather in pools, fluttering in the airflow like the vocal sacs of chirping frogs. From here, they leaked onto our laps, courtesy of the weathered 55-year-old top seal. But the wipers weren’t the only system on strike; so were the temperature and oil pressure gauges, the brake-light switch, the driver’s door lock, and the parking brake, plus, eventually, something even worse. We were flying fast and loose in a powerful and achingly loud muscle car, and it felt sketchy, exciting, and alive. And suddenly damned familiar, because I’d been here before, 40 long years ago.

Summer 1981: In a rural backyard near a stand of sweet-smelling conifers in South Lake Tahoe, California, sat the sorry ragtop. Running but crippled by a blown clutch, it had been pushed into the meadow like an old glue horse led to pasture and left to wither three years prior. Only by chance had I seen the classified ad in the Tahoe Daily Tribune: “1967 Pontiac GTO convertible. Manual transmission. Needs work, $650.” Random travels had stranded me with a one-speed Schwinn Cruiser, an unlikely candidate to ride 450 miles over 8000-foot mountain passes to Los Angeles. I needed a car, and the GTO needed a savior. Sold!

Entering my life between a 1965 Cadillac hearse, a 1976 Checker New York City taxi, and a raging case of wanderlust, the GTO stood little chance of becoming a long-termer. To use a social analogy, it was like hitching a ride home with somebody you met on vacation, having a one-nighter, and never seeing that person again. “I used her, she used me but neither one cared/We were gettin’ our share,” sang Bob Seger in 1976’s “Night Moves.”

Midmorning on that Tuesday, August 4, a tow truck hoisted the front of the GTO, plowed through the tall fescue and up to the street, hooked a right and then a left onto the local highway, and ambled three miles to Kingsbury Automotive & Supply. A new clutch for $217.40, an F70-14 bias-ply whitewall pulled from a gas station’s used tire stack for $15, a check of radiator water, engine oil and tire pressures, and I was on my way, with the Schwinn stashed in the trunk.

Barely into my 20s, I’d already owned two dozen cars and motorcycles, and thus I knew the GTO was special. Which is why, two months later, after a summer of surfing, partying, and burnouts, a nagging feeling accompanied selling the convertible. But there was stuff to do, namely retrieving my possessions from the Big Apple, and a taxi purchased from a Haitian cabbie seemed way better for that job. But that’s another story. Anyway, the GTO vanished like that one-night stand.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

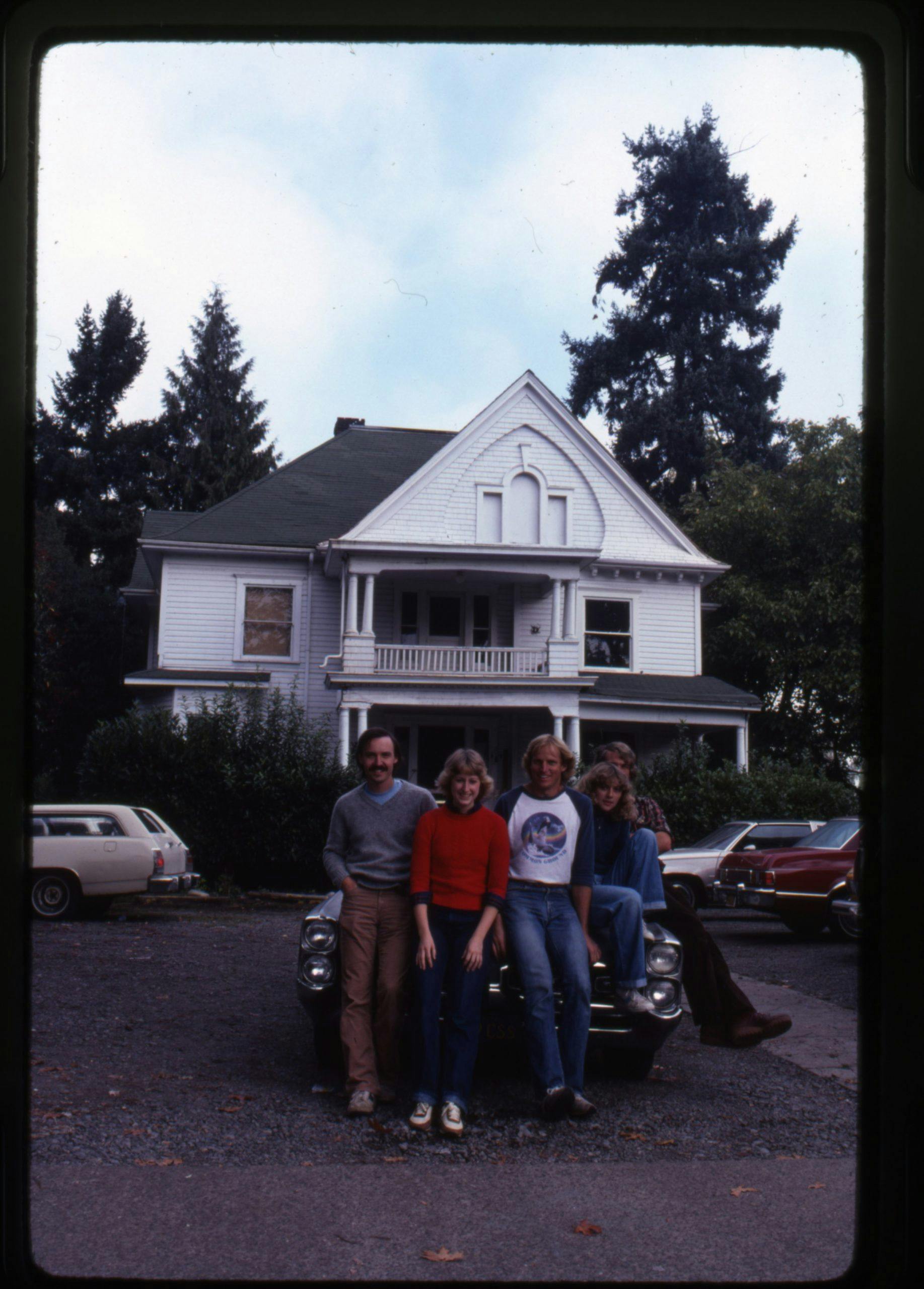

Nearly four decades after dispatching the GTO, I answered the phone. “This is Andrew,” a voice said. In 1974, I met Canadian Andrew Morin in an English youth hostel while vagabonding around Europe. Both crazy about cars, bikes, and adventure, we got along great and stayed in touch afterward. “I found your GTO,” he said. “It’s in Calgary.”

The words froze me like a door hinge creaking in the night. “Are you kidding me?” I answered, grasping for focus. “Who? Where? How?” As Andrew rolled out the info, I could see it clearly. The guy I’d sold the GTO to in British Columbia parked it for 28 years before selling it to another Canadian, an engineer named Rob who is coincidentally a friend of Andrew’s. One day last year, Andrew asked Rob about the car. The story goes that after Rob and another owner, it went to Steve Bacovsky, a Canadian collector, whose email Andrew tracked down and provided. After connecting and sending Steve my vintage photos, I found myself typing the words every car guy knows: “If you ever want to sell it …” The letters—common ones, not even decent Scrabble points—coalesced into words slowly, haltingly, like forbidden fruit budding on that ancient tree. The GTO was tempting but a temptress, virtuous but a vixen. I knew it was right. I knew it was wrong. I clicked “send.”

Months passed, and the GTO reversed to back of mind, just as it had many times before. But one morning the creaky door blew open when Steve wrote back. He’d found a Hemi Belvedere and, on his game board, a Mopar trumped a Poncho. The GTO’s sudden availability forced some deep soul-searching; I’d long hungered for the car but really didn’t need it. Money’s always a thing, space is always limited, and there’s never enough time. I walked into the garage, sat on the stairs, and pondered my internal-combustion geode. And the more I thought about it, the more complicated the GTO seemed.

In your 20s, life is simple. If you want it, make it happen—and if it can’t happen now, well, you can always do it later. But now that it was later, well, the opportunity seemed rather pressing. Candidly, I felt selfish pursuing the car. The unknowns, including whether an old Goat could drive 2000 miles and across an international border, were also concerning. It all seemed like a big hassle. But contemplating who I’d become if I didn’t at least try was more terrifying. I mean, who wouldn’t want to be loose on the land in a Pontiac GTO, thundering across the Rockies and down the Pacific coast? As it turns out, “YES” earns more Scrabble points than “LATER.” I said yes.

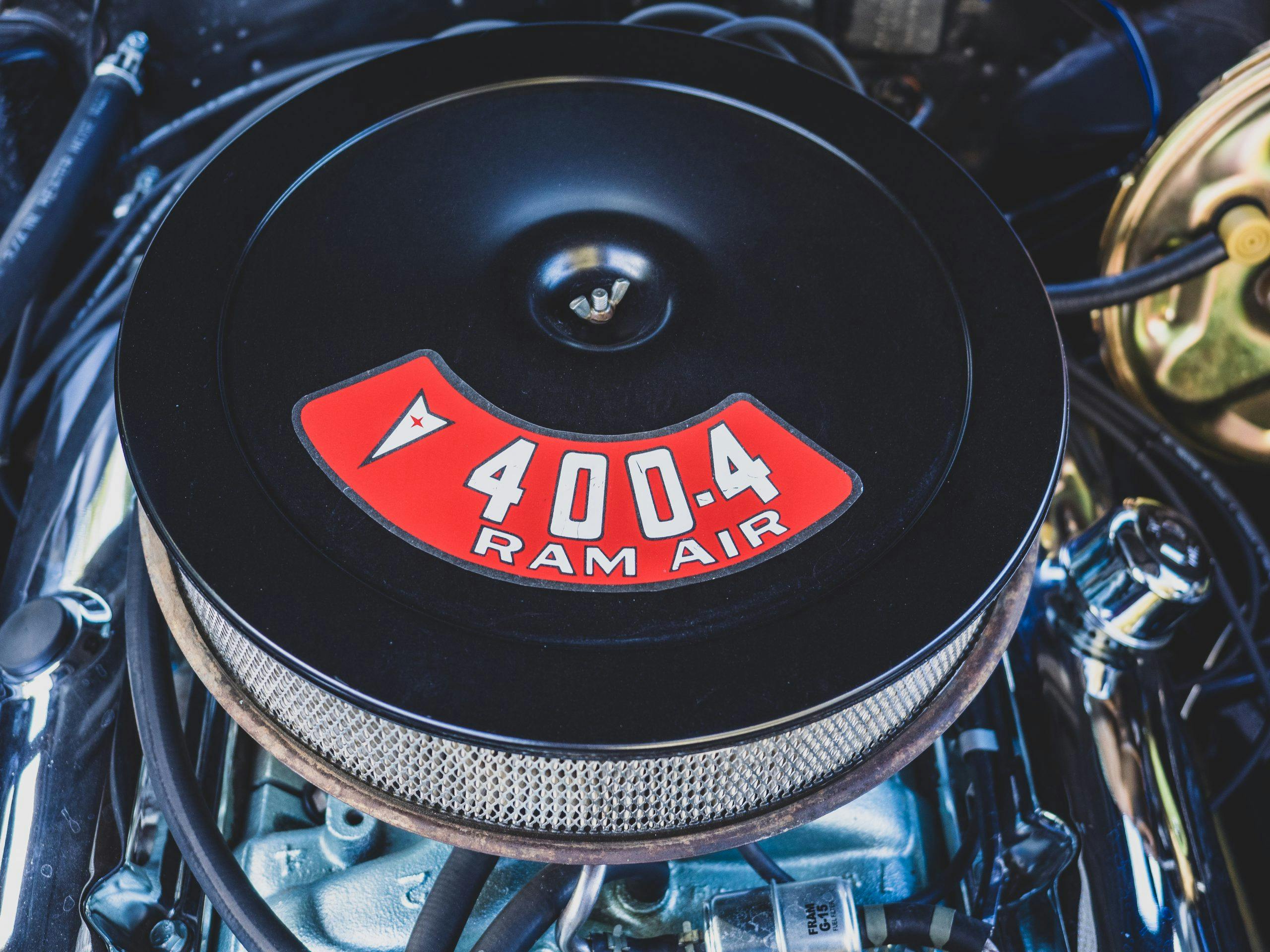

During that long-ago summer, I had liked the GTO immediately. It was fast, the Muncie four-speed shifted great, and the new clutch made sublimating the rear tires into heinous, glorious, acrid smoke easy and fun. On the two-lane linking Tahoe and LA, all was bliss, despite the torn original top flapping overhead, the rear window yellowed to opaqueness, and the rusted exhausts rumbling below decks. Yes, the GTO was wounded and probably so was its driver, in between school and jobs and searching for direction in life. Weirdly, we were perfect together, two castoffs on an open road. And the Pontiac’s big-block omnipotence made this freedom even better.

Driving through the eastern Sierras felt divine. Jagged snowcapped peaks thrusting to 14,000 feet above my right shoulder, sharp sunlight on my face, and the effortless torque produced an unexpected sense of command. Maybe that was life’s tonic, being in command. However, the car drove like a bus with a race engine, meaning fast in a straight line and elephantlike in the turns, thanks to its manual steering and brakes. But so what? Because GTO.

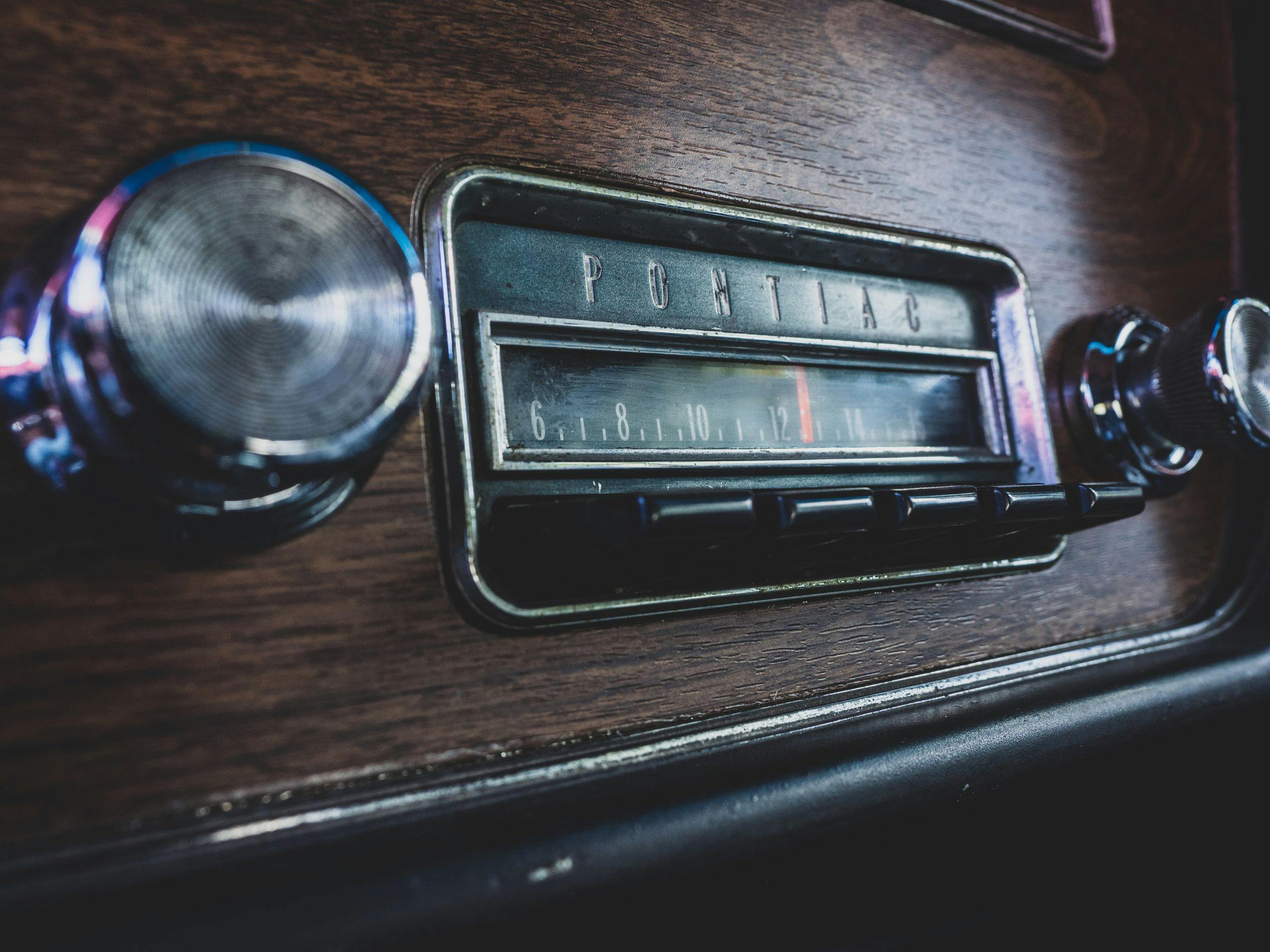

Reuniting with the car in a Calgary storage facility, I was surprised to see the Route 66 water transfer I’d placed on the right vent window in ’81. It still had the same convertible top that Robbins Auto Top in Santa Monica had installed for me, and a small crack in the steering-wheel rim, a flaw felt every time the wheel was shuffled during one of the GTO’s long, lazy turns. But the biggie was a charred edge of the woodgrain instrument panel where, years earlier, a driver’s cigarettes in the ashtray below had exacted their toll. These oddities, which would mean demerits in show judging, heartened me because I craved evidence that the car had lived, that it had a past, that I had been a part of it, and it had been a part of me. Largely, restoration had erased those signs in pursuit of perfection. I was glad a few remained.

When I first bought the Pontiac, it was just 14 years old and its odometer showed under 90,000 miles. Now it read 92,894 miles, meaning it was about to drive farther than it had since Richard Nixon was president. On a sunny morning in late 2021, the old Goat steered west, from flat-as-a-pancake Calgary toward the Canadian Rockies, those formidable sedimentary bulwarks softly wooded by spruce, fir, and trembling aspens now at peak foliage. The forests and roadway here are sculpted by numerous lakes and rivers, some spectacularly green from suspended minerals. Road signs warn of moose, deer, mountain goats, and avalanches. It’s a wildland here; nature still runs the show.

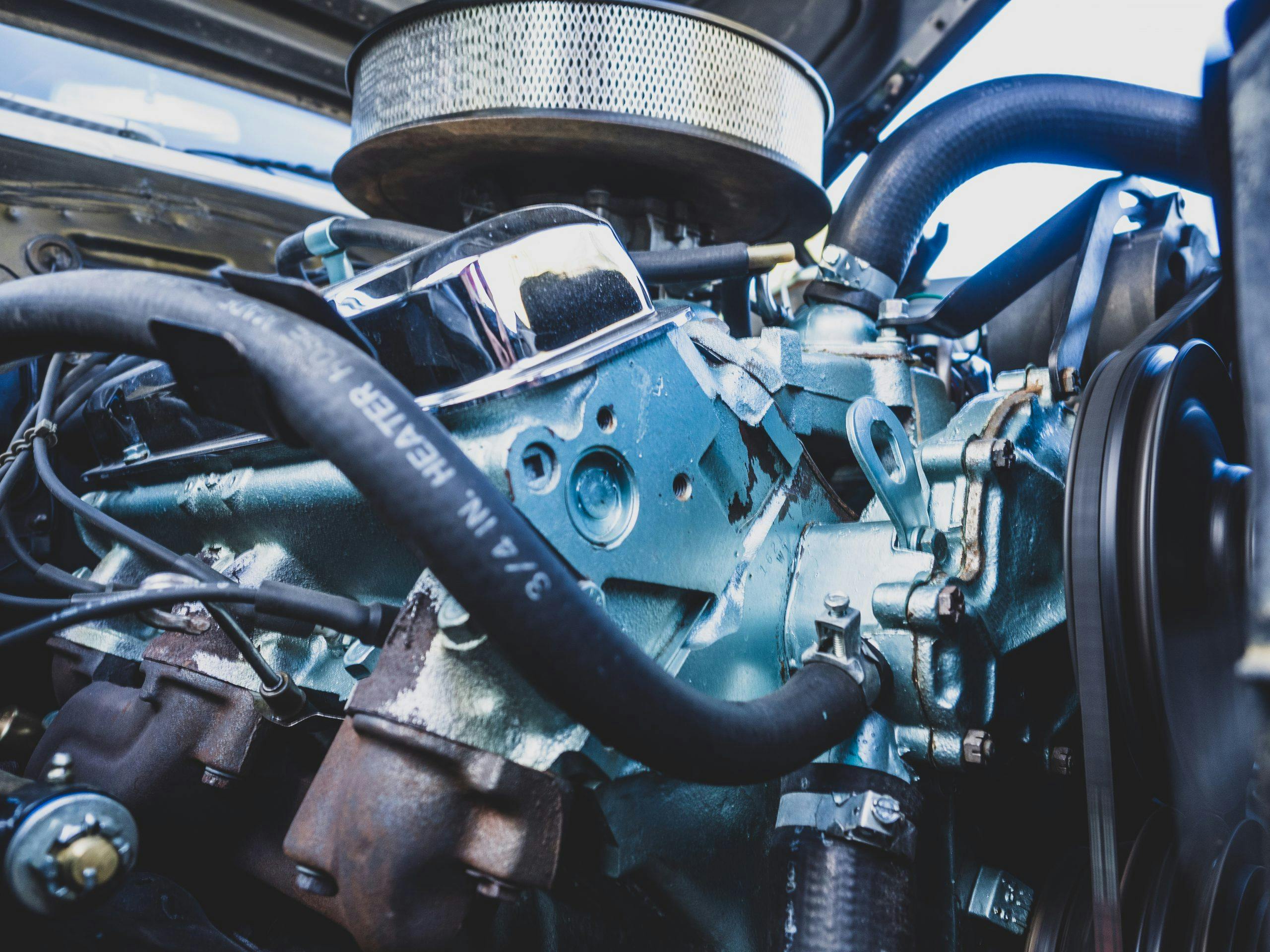

The car needs a five-speed to soothe the big motor on the highway, so copilot Andrew and I kept it to about 3300 rpm, or 65 mph. That was just as well, because with the vainglorious mufflers, the interior sound pressure measured 89 decibels, a perfect cocktail for hearing loss. The rebuilt, hot-rodded engine also occasionally misfired, a disconcerting hiccup in an otherwise stout mill. Despite assurances that the car was road-ready, it had a lot of other issues from the get-go, including the non-op temp and oil pressure gauges and dead wipers. With care and diligence (and some luck) we got to Vancouver, 650 miles down the road, in two days. There, Andrew and I stayed at a mutual friend’s house and spent Day Three of the trip tackling problems. New sending units rectified the temp and oil pressure gauges. I drained the supposedly clean oil to find really dark, old oil instead, and so we replaced that and the filter. A disconnected wiper-switch ground under the dash explained the stalled blades, so I soldered up a shunt using a copper washer and grounding wire that worked. At last, we were in motion again.

At the U.S. border near Vancouver, the agent questioned why the GTO’s Alberta plate didn’t match my U.S. passport. After I explained, he asked, “So you’re buying it?” Then he sent me inside an office that seemed frighteningly paramilitary. But I had the right paperwork, and Customs clearance took only about 10 minutes. Then we were free to go.

After inching through crowded Seattle and Tacoma, we happily swung west toward the Washington coast and soon were among calm Northwest waterways, woods, and farmland, with tidal flats to the right and hay bales standing like the Queen’s Guard in autumn fields to the left. Rain again struck the windshield, this time great, fat drops that spattered like miniature asteroid strikes.

All the while, in fits of indecision, the two-lane threaded left and right, up and down, and finally to the Pacific. Lazing along in third gear, the GTO passed groves of stunted cedars, hunched over rock faces in the onshore wind like toiling peasants, and forsook tangles of plump blackberries, ripe for picking. Among the sporadic oceanfront towns, some looked purposeful, prosperous, and well-maintained, while others seemed poorly planned, seedy, and disjointed, their raison d’être, fishing or logging, long since abandoned. The Goat could make mincemeat of this humble highway, but there was no point. As with a photographic image slowly emerging in a darkroom’s developer tray, when traveling, a sedate pace deepens appreciation.

Pontiac GTO s/n 242677B108879 drove off Pontiac Motor Division’s Baltimore, Maryland, assembly line in early November 1966, destined for Lawless Cadillac-Pontiac in Worcester, Massachusetts, and carrying a sticker price of $3834.80. Painted Silverglaze over a black vinyl interior, it had the 335-hp, 400-cubic-inch V-8 with a four-barrel Rochester carb, bolted to a wide-ratio gearbox powering through a Safe-T-Track differential with 3:55 gears. The black roof was power-operated, and inside, under the dash and optional Rally gauge cluster, hung a factory eight-track tape player. “Eighty minutes of uninterrupted stereophonic sound-in-depth,” promised Pontiac’s 1967 brochure.

Quick-ratio steering, manual drum brakes, and Rally I wheels were fitted, along with special ride and handling springs and shocks. Whoever ordered the car was likely a good-time Charlie who wanted the most fun for his money. Or maybe a good-time Charlene; I don’t know which.

But I do know that on March 14, 1970, the gent I first bought the Goat from purchased it used from Bancroft Motors, likewise in Worcester. He paid $1995 and traded in a 1968 Dodge Coronet 440 hardtop, for which the dealership kindly credited him $1395. In early 1973, the GTO migrated to San Jose, California, where it lived until moving to Lake Tahoe. Soon afterward, its clutch scattered and it got parked, its race run. From hero to zero in a decade, such was the life of ’60s muscle cars.

Almost without warning appeared the Columbia River, where Lewis and Clark culminated their long trek from St. Louis in 1805. The Big River is eponymous in that it looks more like a bay, but we sailed easily over it thanks to the Astoria-Megler Bridge, North America’s longest continuous truss and coincidentally one year older than the GTO. Mercifully, the daily rain showers abated in the afternoon, which brought dappled sunlight, raking through the forest canopy and dancing off the lissome fender lines and hood scoop. Occasionally, the winding route allowed glimpses of the craggy coastline, the ocean restless and pounding against obstinate rocks, attacking the continent and tearing it apart, grain by rocky grain, a century at a time. Once, when Andrew arced through a long sweeper, still wet in the shade, the back end stepped out. He countersteered quickly but it was a good reminder: There’s no stability control here—just the BFGs and the driver.

From Alberta and British Columbia to Washington, Oregon, and finally California, the Beaver State definitely showed the GTO appreciation. At the Tillamook Air Museum, middle-aged Barbara made a beeline to the car, her hippocampus redlining as she recounted driving her boyfriend’s ’66 GTO with a 389 and a console shifter, and how just tipping the gas pedal had snapped her head back. Then, later that afternoon, a young, burly and wildly inked Jason at a gas station commented, “Nice Goat!” Although sighting a GTO in the wild is rare today, people still know and remember.

Coos Bay, a former logging town, is on a protected inlet along Oregon’s southern coast. We found that Olympic runner Steve Prefontaine’s boyhood home was just a few miles off our route, and being a masochist—er, being a runner myself—I was drawn to seeing it. In front, neighbors were talking. One was Pre’s friendly sister Linda, once a nationally ranked athlete as well. She revealed her famous brother was a car guy, too. He had two MGBs, and earlier, a black Tri-Five Chevy with a Hurst shifter, in which he enjoyed cruising Coos Bay with his high school buddies. “A lot of people run a race to see who is the fastest,” Prefontaine once said. “I run to see who has the most guts, who can punish himself into exhausting pace, and then, at the end, punish himself even more.”

The GTO’s niggling problems—including the persistent misfire, the driver’s door lock that failed when a linkage clip slipped off inside the door, a barely working parking brake, and the leaky top—meant that maybe this trip had something in common with Pre after all. That afternoon, under pastel skies, we proceeded farther south, still hugging the coast. Inspired by Pre’s life, Oregon’s spectacular bluff-top views, clear streams flowing seaward, and driftwood piled on the wild beaches, I parked and scrambled down a trail to run on the sand, smooth and hard-packed, pitching gently toward the Pacific.

Entering California soon brought us to Trinidad for gas (12.8 mpg trip average), a fish and chips dinner, and a Steelhead ale. Unexpectedly, the GTO attracted more attention here. A fast-talking surfer fueling his diesel rig announced with hubris that he wanted to steal it. Sketchy but whatever; insured! Then a hippie lady, Sandi, floated up to us. Wearing a tie-dyed shirt and curly Janis Joplin hair, she wanted to know what year the Goat was. Then while we were dining, a slickster wearing a Hawaiian shirt, a gray ponytail, and a smile approached. “I don’t have a business card,” he cooed. “But I have cash and would like to buy your car.”

Good thing the Redwood Highway was constructed in the early 1900s, because it would likely be impossible today. Call it sacrilege or spectacular—or maybe both—but driving through this living cathedral with the top down was simply otherworldly. So was the realization that 40 years ago, I’d headed north beneath the same trees in this same car to deliver it to its next owner. Same road, different directions, different centuries. My mind whirled trying to comprehend it all.

Now as then, it’s dead silent in the forest, where tree canopies stretch skyward to mesmerizing heights. The cool and damp air, the deep, cushiony duff underfoot, and the shadowy light filtering to the ground are surely Tolkien-esque. And the dimensions of the old-growth redwoods are equally mind-bending, with trunks up to 20 feet in diameter, reaching 28 stories high and surviving since the Middle Ages. Comparatively, man counts for nothing—except for our historic ability to screw nature over. GTO Owners & Tree Huggers, unite! Nearing wine country, we hatched a plan to peel toward Bodega Bay (to hunt for the Aston Martin DB2/4 from Hitchcock’s The Birds), navigate San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge and, in one more day, glide home. The Goat never made it. Negotiating a parking lot in little Garberville, the GTO’s retrofitted power steering pump suddenly groaned, low on fluid. I killed the engine, shimmied under the front bumper, and found the circlip, dust washer, and seal displaced from the Saginaw steering box, and the pitman arm covered in fluid.

After consulting with two repair shops, I decided to remove the pump’s V-belt and proceed. At this point, the GTO felt reminiscent of the famous World War II B-17F named All American, which, after colliding with an enemy Messerschmitt over North Africa in 1943, managed to limp home to base with her tail nearly severed. Our strategy worked acceptably until a gas stop in equally tiny Hopland, a few hours hence, where the steering coupler alarmingly began ratcheting on the steering box’s splined input shaft.

While we investigated, Craig Frost of nearby Shadowbrook Winery stopped in his pickup. He owns a classic 1966 Toyota FJ40 and, recognizing that an old car with its hood up meant trouble, kindly offered the GTO safe haven in the winery’s nearby barn. Here, further inspection revealed the steering coupler’s pinch bolt was inexplicably loose. At this point, recalling how a broken steering column caused Ayrton Senna’s fatal accident, and an ambulance ride of my own after a brake failure caused a racing crash, I called the trip. I’d been OK driving sans power steering, but not with potentially damaged steering splines. We’d made it 1600 glorious miles, and my only regret was seeing the Pontiac on a flatbed. But the roads are still there, the Goat is still in one piece, and, most important, so are we. As Chuck Yeager drawled, “If you can walk away from a landing, it’s a good landing.”

Poetically, the GTO’s failure perfectly restarted our relationship, because it entered my life wounded in 1981 and it reentered my life wounded in 2021. So perhaps this little GTO actually still needs me. Which is good, because now, I definitely need it.

1967 Pontiac GTO Convertible

Engine: 400-cubic-inch V-8

Power: 335 hp @ 5000 rpm

Torque: 441 lb-ft @ 3400 rpm

Weight: 3522 lb

Top speed: 124 mph

Price when new: $3834.80

Hagerty #2-condition value: $82,250–$105,500

Awesome story, I have a ’67 GTO hardtop, that I bought in High School before going in the Navy. I bought it in Illinois, but it had California plates, and a NAS Alameda base sticker on the windshield. My second ship was out of the Bay Area, and I spent a lot of time at Alameda.

Your story really gets my memories going! Thanks, I hope you do a follow up!