Media | Articles

Driving Citroën’s infamously complex SM is pure delight

Don’t be fooled by the golden sunshine and U.S.-adjusted spelling; this piece hails straight from soggy, grey Britain. Enjoy the view from the righthand side of the dash! —Ed.

The standard reaction to telling someone that you own a Citroën SM is generally one of incredulity—“You’re brave!” How do I know? Because I owned and restored one, and because fellow SM owners laugh about it, though quietly, so as not to tempt fate.

But what do those owners say? Usually that it’s the best car they’ve ever owned. The SM gets under your skin like that. There’s nothing like it, though if you ignore the timeline you could say it’s the high-functioning lovechild of the Citroën DS and the Maserati Merak (which came out two years later with the same engine and transmission). In so many ways it’s significantly better than the sum of its unlikely parts.

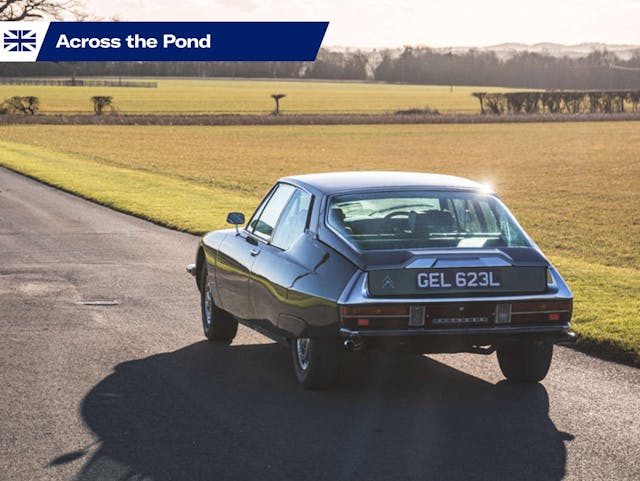

Those parts are mostly Citroën, and mostly unique to the SM, starting with the sleek, two-seater, fastback body, styled by Robert Opron. When Opron passed away in 2021, his achievements were lauded but until then he’d often been overlooked, despite having been responsible not just for the SM at Citroën but also the GS, the CX, and even the rotary-powered M35, among others. At Renault he styled the 19, 21, and Fuego and may well have influenced the Espace. And before any of that, he came up with the futuristic self-driving Simca Fulgur concept, first shown in 1959.

To this unusual body was added a compact V-6, designed for the SM by Maserati’s Giulio Alfieri, mated to a five-speed transaxle. The whole lot sat on Citroën’s trademark hydropneumatic suspension. The original concept for the SM was for a sportier alternative to the DS but the project soon turned into a grand tourer showcasing the company’s innovations such as speed-sensitive steering.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

When the SM was first shown, at Geneva in 1970, it caused a sensation. Where it later fell down was, in a way, its association with the rest of Citroën’s more run-of-the-mill models, as well as the low-volume, slightly under-developed nature of its production. The Maserati engine in particular required more looking after than the rough old lump with which the DS was saddled, and owners used to the basic controls of cars of the 1960s and ’70s struggled with the sensitive responses of the SM.

Now, we know what the problems were and how to prevent them, but back then it wasn’t long before the SM gained a poor reputation for reliability caused by garages failing to treat the Maserati engine like the thoroughbred that it is; irregular oil changes and cam chains left unadjusted caused the most problems. Production continued until 1975, encompassing a move from 2.7-liter to 3.0-liter capacity and Bosch D-Jetronic fuel injection in place of triple twin-choke carburetors for some markets. Just 12,920 were built.

The reliability issues are now mostly irrelevant, and the SM provides a driving experience like no other, from the moment you swing open the long door and drop yourself over the stainless-steel door step trims into the one-piece seats, whether they’re the leather or fabric finish. Unless you’ve found one of the ultra-rare, aftermarket conversions, you’ll be in the left-hand seat to drive.

The SM will be sitting low, until you twist the slim ignition key. The V-6 fires up and immediately sounds rortier than you’d expect, considering the serenely civilized styling both inside and out, and a blip of the throttle just cements the surprise. Meanwhile, the hydropneumatic suspension comes to life, as the engine-driven hydraulic pump starts to pressurize the suspension spheres, pushing the car upwards into its normal side height.

While we’re on the subject, a lever to the left of the driver, sticking out of the sill, allows an extra low or extra high suspension setting. This provides no end of fun, though it takes a few seconds for the system to react and start to adjust the height.

With the suspension settled, try turning the steering wheel then letting go, to see it self-center of its own accord. Weird! Then into gear, which if you’re in the five-speed manual is via a polished metal, open barrel gate, à la Ferrari. The clutch is light and the shift action more mechanical and precise than it has any right to be, given that the transmission sits ahead of the engine, right at the front of the long engine bay.

And maybe acclimatize to the brake pedal too at this stage, because it’s actually not a pedal at all but a small rubber-covered button right on the floor, with just millimeters of movement between no brakes and full, seatbelt-straining actuation of the all-round discs (in-board at the front). Once you’re comfortable being more gentle on the brakes than you’d be used to in any other car of this era, you can head off for the full SM experience.

It’s immediately, and obviously, strange. The hydropneumatic system keeps the suspension level, and the huge bonnet seems to float in front of you as the SM glides over every imperfection. Meanwhile, the engine pulls strongly, needing revs rather than being able to rely on torque, its intake—particularly on carbs rather than injection—as vocal as its exhaust.

Before long you’ll be gliding along at higher speeds than you might have expected, adapting to the hydraulically powered steering that cleverly adjusts the hydraulic pressure to the rack according to speed, reducing the steering assistance the faster you go. This allowed the steering to be geared for just two turns lock-to-lock, in an era when most equivalent cars would have needed at least twice that number of turns. At the time, there were reports of drivers swerving from left to right as they struggled to get used to it. Now, when such tales are reported, take them with a pinch of salt, because we’re all far more used to similarly reactive steering. It’s just the SM was 40-plus years ahead of everything else.

Other features, similarly groundbreaking in the 1970s, don’t seem as remarkable now: often it’s the methods used that are more mind-boggling than the features themselves. Take the headlights, which have one fixed pair, one pair that self-levels and another that turns with the steering to illuminate the corners (except in the U.S., where regulations forced boring, fixed lights). They’re operated by a series of rods, levers, and hydraulics that have a wonderfully Heath Robinson feel to them—but not only do they work but the way they work is clear to anyone who takes time to look.

Likewise, the windscreen wipers, which measure the amount of electrical current needed to power the blades across the windscreen, and adjust the speed of the sweep accordingly. There’s a simple logic to all the extra complication.

And so gradually the idiosyncrasies start to feel more normal, and before you know it you’re gliding along, getting used to the float of the suspension and the way that the car squats evenly rather than diving even under hard braking, feeling more confident pushing harder into bends and finding that this large machine with its slightly disconnected feel actually grips hard on its unusual, metric-sized Michelin XWX tires (the default choice for an SM). There’s a reason for the grip, and that’s the way the powered steering allows the SM to run near-zero caster angles; along with having no camber change as lock is applied, meaning the maximum amount of tire area is kept in contact with the road at all times.

The engine feels and sounds sporting on acceleration but is quieter when it’s cruising, and that’s when the SM really comes into its own, sweeping majestically through the countryside, smoothing out every road surface and attracting admiring glances wherever it travels. You can push an SM hard, but the car won’t thank you for it. Better that you take advantage of the cosseting ride and the feeling that you’re in something truly unique and special, learning the idiosyncrasies of the handling and the steering and braking response, getting the best out of the engine and proving the non-believers wrong.

A good SM is a phenomenal machine that everyone should experience if they get the chance.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

We had a local dealer for these in Ohio. He sold so many that he kept two in stock and they sat inside a local mall all the time as they never sold.

I recall seeing them as a kid and I knew what they were due to the Matchbox car I owned. Odd cars with strange engineering and heritage.

If I recall you could take the hydraulic suspension and set it to change a tire without a jack. Then pay dearly when it failed.

You are correct! I worked in a tire shop 1978-80 which sold Michelin and Goodrich exclusively, so we saw lots of (on the Michelin side) imports.

To change a tire, you would set the suspension on full high, then place the supplied support bar in the correct location – the details of which escapes me at this point – then set the suspension for full low. The car would drop down until the support bar hit the ground, and then lift the tires on that side into the air. So cool!

I don’t recall if these had the steel wheels without a center hole, but if they were, then it was all hand tools to R&R the tires, and I think that they may have come with tube type tires as well.

I remember Citroen’s ad slogan in the ‘70’s. It went: “In all the world, there are but two kinds of cars: “Citroen,….and all the rest.”