Media | Articles

Vellum Venom Vignette: Just call a crossover a car already!

Driving a vintage, classic, or antique four-door sedan of any national origin is quite the ordeal on urban roads these days. Yesteryear’s low-slung beasts get absolutely lost in a parking lot full of crossover utility vehicles (CUVs), while the minuscule Nissan Kicks looks down upon you in traffic. And good luck taking a right turn in your saloon if a Toyota RAV4 pulls in the next lane looking to take a left. Times have changed, and automotive nomenclature needs to reflect the transition: The CUV is the modern car, plain and simple.

I appreciate the CUV’s value proposition, most easily found in its two-box design and taller overall height. Instead of the traditional three-box (i.e. front box for engine compartment, middle box for passengers, rear box for cargo) design of sedans, CUVs have a large second box for either passengers or cargo, complete with a usable hatchback configuration that provides a wide-mouth opening for stuff.

Now add the CUV’s taller ride height, which is great for daily chores, heavy snow/rainfall, and forward visibility. It’s no surprise why the sedan is on death watch, but there was also a time when cars really, really looked like CUVs.

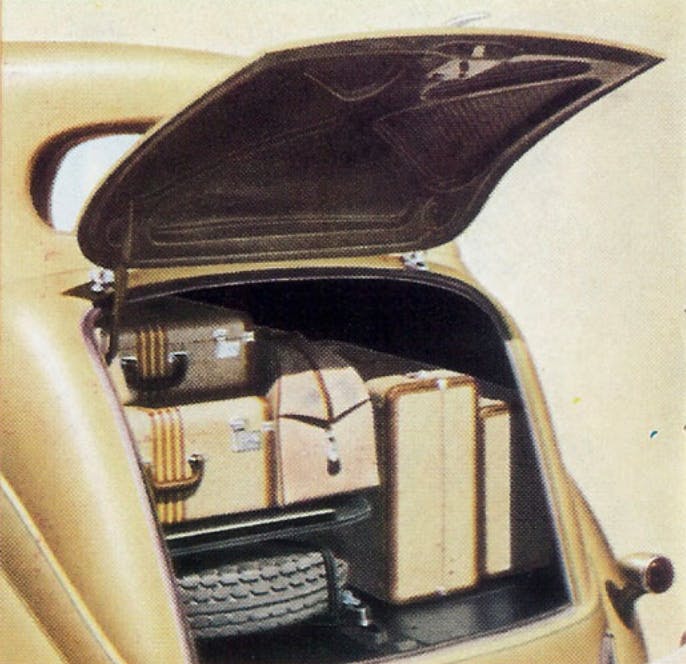

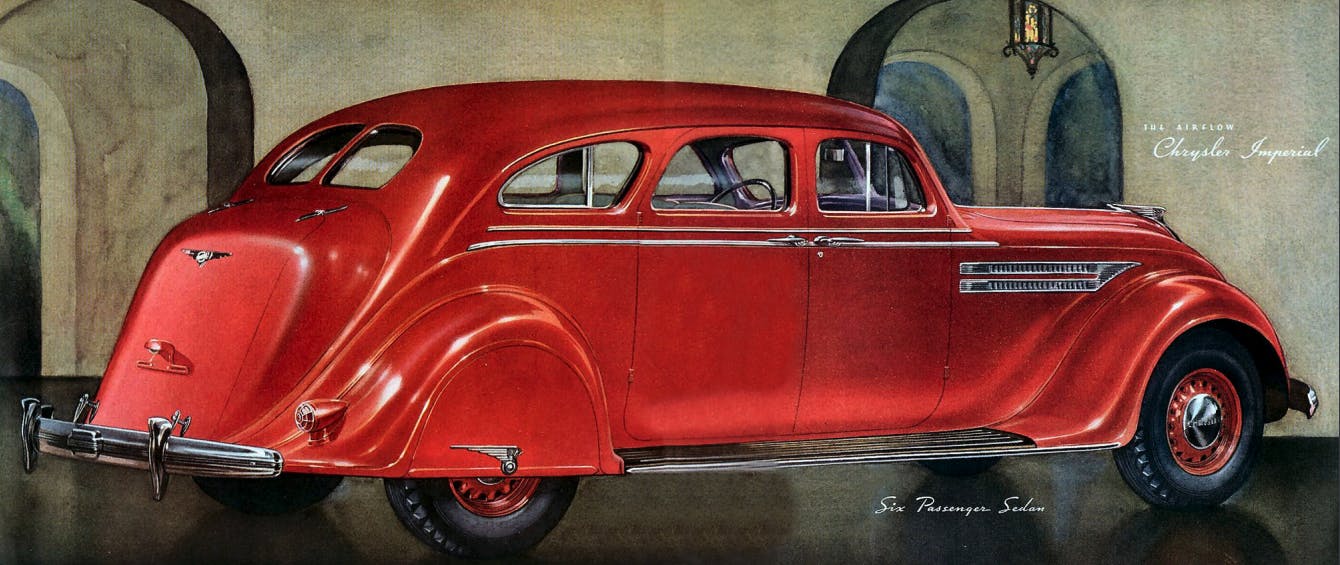

CUVs are cars because cars used to be CUVs. Prewar bodies were tall, had daylight openings (DLOs) that comprised only a small percentage of the bodyside’s real estate, sported an upright seating position, and had rear trunk mechanisms that operated more like a hatchback. And those trunk/hatch affairs were tiny lumps in the posterior, arguably making them more of a two-box design with a small tumor.

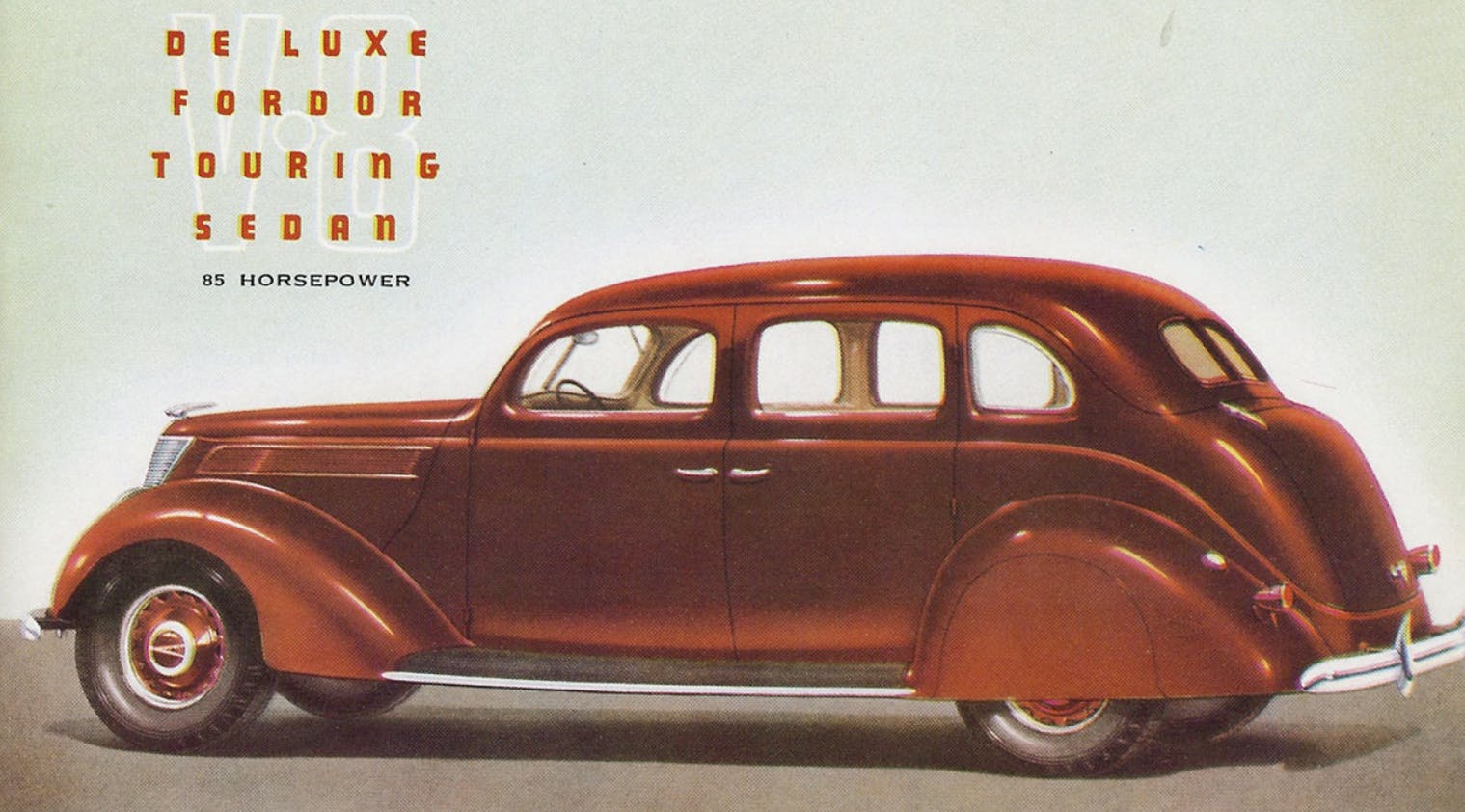

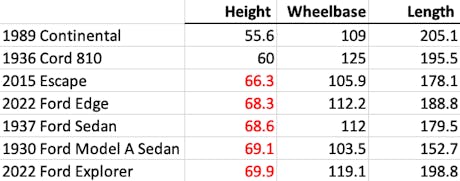

Aside from the CUV’s hatch encompassing the rear window, how are older sedans not the unintended blueprint for CUVs? More to the point, finding a 1930s car with a proper three-box design is harder than you’d expect. Take the 1937 Ford pictured above: The “sedans” were two-box CUVs, while the coupes and cabrios were proper three-boxers. While that’s just Ford’s offerings from 1937, the portfolio kinda foreshadowed Dearborn’s sedan-free future some 80 years later. Keeping with the Blue Oval theme, see how a smattering of other Ford CUVs fit in relation to Ford cars from the 1930s.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

We focus on the side-profile dimensions because, as our in-house design guru Adrian Clarke says, “The volume of a car is its basic shape—the outline of the bodywork when seen from the side.” Vehicle height is crucial in this discussion, because it’s one of the CUV’s strongest selling points.

The traditional sedan is now the outlier, as if decades of Harley Earl’s longer, lower, wider school of thought were somehow wrong. Somehow bad for us, and perhaps only worthy of niche vehicles like the Cord 810. The evolution from Cord-like sedans to the 1989 Continental prove the three-box sedan could only evolve so far. Which begs the question: Are the sedans still produced today worthy of being called sedans in the purest, most Harley Earl sense of the definition?

Possibly. Sedans like the current Camry still have a three-box design, but that rearward box has been shrinking in length and growing in height over time. The sweeping, fastback roofline also minimizes the presence of the third box, but exactly how much taller is the height of these modern monstrosities?

With less overall length to spread the design across a canvas, the modern sedan looks like it’s moving skyward. But your eyes don’t lie, as even a Toyota Corolla stands almost two inches taller than the flagship Lincoln.** Part of the height increase is due to pedestrian safety regulations mandating taller cowls, but that’s a topic for another day. Instead consider this notion: Perhaps the sedan actually died in 2011 when the properly three-box Panther-chassis Fords met their maker?

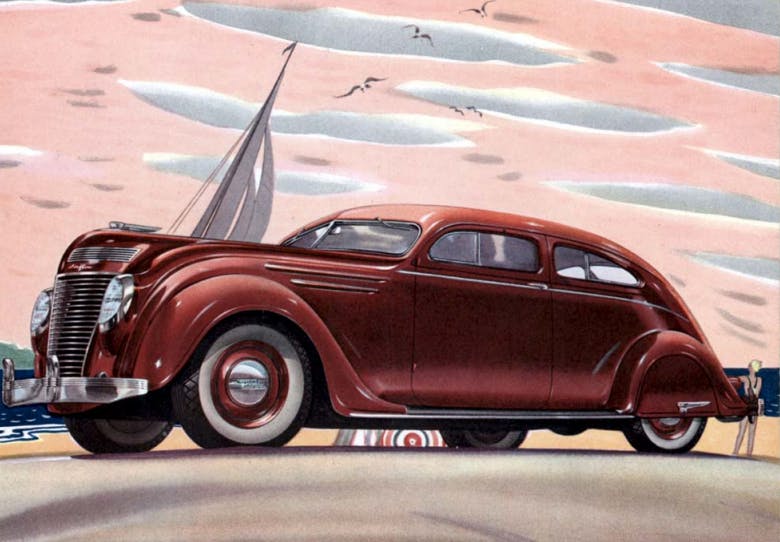

And with the arrival of the new Chrysler Airflow CUV, I can’t help but wonder if we’ve finally come full circle. We are making cars (sorry, CUVs) with side profiles reminiscent of the upright-nosed, tall, and streamlined 1937 Airflow pictured above. Perhaps CUVs are also challenging the need for a 3-box design in our society. And at what point do we care about calling some designs “cars” and others as “crossover utility vehicles”?

Perhaps we should wrap things up with the fact that designers don’t live in a complete vacuum; they know which vehicles are a higher priority for their corporate taskmasters. CUVs are a dominant sales force, and everyone in the supply chain is content with that reality. Take automotive retailers and the OEM personnel that support their plight, as they see higher CUV transaction prices, lower rebates/incentive costs, and often shorter inventory holding times. Perhaps this tidal wave of evidence to the CUV’s nature as a “real car” is irrelevant to some, but there’s one question that Chrysler asked that rings disturbingly true to this day.

Who indeed? The collective buying power of CUV fans is inescapable, as is the need for taller vehicles to pass the same pedestrian safety standards that ultimately destroyed the three-box design aesthetic. Perhaps car design goes where the money goes, and where the regulations take them. Long live the CUV … I mean the car.

Thanks for reading—I hope you have a lovely day.

**While the 1989 Continental isn’t anyone’s first choice for the three-box design’s masthead, it’s a median approximation of the sedans in our past: part stereotypical American land yacht, part high-zoot foreign sedan. It’s an American E34 BMW 5 Series with a lot more junk in the trunk. And it was also conveniently parked in my garage … but no matter, we got the representative needed to prove modern sedans are disloyal to the decades-old, three-box design aesthetic.