Media | Articles

Vellum Venom: The Virgil Exner Jr. Interview (Part II)

When we last spoke with Virgil Exner Jr. about his career, I promised readers they would have the chance to ask him questions. And that’s precisely what happened, as I received numerous questions from the comments in the article. (And from my social media followers, to be honest.) I jotted them all down, spoke to Exner Jr. on the phone, and got his answers to your queries.

I would like to personally thank Virgil Exner Jr. for working with me to respond to your questions. Not too many folks in the car design world are willing to answer any question you may ask, but he did just that. And on Friday, April 4, Exner Jr. celebrated his 92nd birthday, so I ask that we all celebrate him on this special day!

Hagerty: What are your thoughts on today’s design language?

Exner Jr.: It is pretty simple, style is missing when it is applied to car design. There are many other factors involved in designing a car, and style is no longer a high priority.

H: Does excitement play much of a role in design anymore, especially in a world filled with mundane crossovers?

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

VE: It definitely, obviously does not play much of a role! There doesn’t seem to be much excitement at all toward car design. People these days seem more interested in the technology and software inside them.

H: Are there any designs you were a part of that you particularly disliked?

VE: Not really that I can remember! There was a lot of stuff that people designed for me in a studio that I didn’t like, or the artwork that went with it, but none of that really materialized outside of the studio.

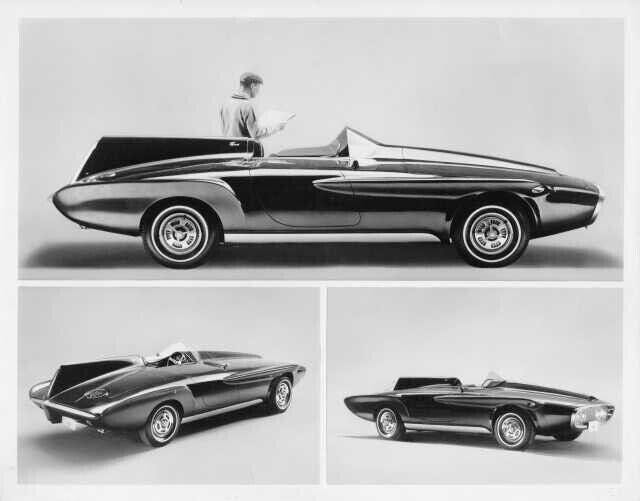

H: I love the Plymouth XNR. Please tell me anything you can about it!

VE: That car was created in my father’s studio back room in 1958. It was seen by a Ghia rep when they were visiting Chrysler, and they loved it! And they actually loved it enough to take the design and the clay model back to Italy to make it into a real car.

H: What are your design inspirations, and which era is your favorite?

VE: My father is my inspiration, as I was brought up to love cars thanks to him. My era has to be the 1950s and ’60s, as these newer designs were so different from what we saw before WWII. This is also when my father created Chrysler’s Forward Look, and nothing after that has moved me quite like that!

H: What does authentic styling in an automobile mean today?

VE: Authenticity does not mean much in today’s design. As I mentioned before, today’s buyer is more interested in technology. I don’t know if styling is as relevant the way it used to be, much less making something truly authentic.

H: Regardless of 1950s aesthetics, what in your mind was your father’s signature styling cue?

VE: Look past the usual design touches of the 1950s, and you see my father presented a lot of aerodynamics in his styling. Many of his concepts incorporated aerodynamics as an integral part of the designs. But he did like to expose wheels and tires, however, in some occasions. Overall he liked slimness in design, and aerodynamics is a big part of that.

H: Could those signatures be incorporated into today’s car designs?

VE: Yes, this slimness in design could happen if people would like that, and it was presented more frequently to them. It is not presented today, and there should be a revival in modern times for this!

H: What did you and your father think of Harley Earl?

VE: We liked Harley Earl very much! He was a real good guy, and my father got along with him very well. I met him when I was 4 years old, when my father was chief designer at Pontiac. When I won the Fisher Body Craftsman’s Guild and went to Detroit for that, I met Harley and he became my friend.

H: Did James O’Donnell [president of Stutz Motor Company] combine the front of the Duesenberg with the back of the Stutz?

VE: No, it was my father’s idea, and that’s what we did for the production car. We added the Duesenberg-style radiator, and I styled the rest of the car.

H: What element of the Duesenberg concept are you proudest to have contributed?

VE: I am proud of all of it, except for the front end. That’s because that part of the car was not mine. The rest of the design was based on one of my illustrations.

H: Did you or your father ever own or have use of a production Stutz Blackhawk?

VE: I cannot remember. I think my father brought a Blackhawk home at the time. But I cannot say for sure.

H: Do you have a favorite revival car?

Note: Four of the seven revival designs made it to reality (Duesenberg, Stutz, Mercer, and Bugatti). The Packard, Pierce-Arrow, and Jordan Playboy were only realized in plastic as Renwal model kits.

VE: Yes! My favorite is the Bugatti Type 101, which we purchased as a bare chassis, and it was designed and built by Ghia. It is my most favorite car out of all the vehicles we were ever associated with. Well, that is aside from our 1932 Indianapolis Studebaker race car.

H: Were you present at the Blackhawk prototype unveiling at the Waldorf-Astoria in 1970?

VE: No, I was present at the unveiling of the Duesenberg revival, and that’s when Henry Ford II visited. This happened in South Bend, Indiana. He was extremely impressed, went back to Ford and demanded new designs because of it.

H: On that note, would you agree that you set the stage for 1970s luxury car styling?

Note: The revival designs were indeed very influential; it has been said that the Lincoln Mark III was inspired by Henry Ford II seeing the Stutz prototype.

VE: Yes, to a great extent! Very much so, we created the revival series!!!

H: Is there a chance of reviving the Exner Duesenberg for a modern production run?

VE: No, I really don’t think so. I say this because there don’t seem to be enough people out there to support this kind of undertaking. There would need to be more people who love that era in car design enough to show more interest.

H: Was Ford Design under Gene Bordinat a political mess?

VE: Very much so, because Bordinat was much more of a politician than a designer.

H: Was Ford different under Jack Telnack?

VE: I worked directly for Telnack, and I saw that he had good taste. But he was not that good of a designer on his own. That is not uncommon nor is it meant to be insulting, because usually the heads of design departments aren’t that design savvy.

Today, design department heads would rather pinch pennies. That’s why design is lacking greatly these days.

H: How it is different being a singular design operation versus the room full of competing designers?

VE: A good example of that is how there were only one or two designers at Ghia. Instead you would have at least 50–60 designers at Ford styling. In many studios, I saw that there were at least four or five designers who were not really contributing very much. But the designers at Ghia were excellent, and the head of the studio just went along with their work. That is the embodiment of the Italian design that we know and love.

H: How did Ghia’s design process differ from the Detroit studio operation?

VE: Ghia went from design drawings and sketches almost directly to banging out a body for the car they were designing. Ghia’s strengths relied on the fact that the head was a car enthusiast, and there were not many weaknesses!

But there certainly were weaknesses in Detroit styling, as the heads of design were not really rip-roaring lovers of cars. My father maintained that racing was the lifeblood of car design, mind you. But in Detroit, it started off with sketching, then quarter-scale models, then three-eighths-scale modeling, then full-size clay, then full-sized models that are painted/trimmed, and then finally shared with engineers who worked with them. From there you get a prototype, and then a production vehicle.

H: There are stories that your father’s design leadership had him creating on his own work, then handing it to the design studio. Is this true?

Note: This question is about his father when he was the head of Chrysler Styling, as there is a notion that he was a leader of design versus a copier of General Motors.

VE: My father was definitely no copier, but he did like some foreign and racing designs. Those influences and the desire for aerodynamics were his main guide. And he had his own private studio with modelers. He did show some of those designs to Chrysler management, and they moved further into production from there.

H: In terms of beauty, what is your favorite race car?

VE: That would be my 1932 Indianapolis Studebaker race car, because my father bought it when he was at Studebaker. It is one of five.

It did not take much work to be turned into a road car, and we drove it to Connecticut every summer to the big SCCA meet! I was the riding mechanic for my father, and I rode in it for about 7000 miles, until my father let me drive it!

H: What did your father contribute to the Ghia L6.4’s final design?

VE: He did not do too much with the L6.4, because that was primarily a Ghia design. The L6.4 was simple and very well done, but unfortunately it was turned down for production by Chrysler.

H: As impressive as your life and career looks to outsiders, was it enjoyable all the time?

VE: Well, almost always! I truly love car design. I still design every day for myself. There were very few times that I got riled up about my job. For the most part it was a great career for me and my family.

H: What is your favorite concept that never saw the light of day?

Exner Jr. thought about this one for bit, as he had a lot of cars to consider.

VE: I had one at Ford that should have been done, but they didn’t do it. I designed a concept for the Ford Pinto, and what I made turned into a basic full-size clay model from my studio.

This concept was turned over to the Mercury studio. They finished it up and showed it to the design staff and finance guys. Those folks criticized the design then made changes I didn’t like.

I made my feelings clear to Henry Ford II. The design eventually had an exposed fuel tank in the rear, and it became the Pinto. This is the same car that led to the fires. But surprisingly, after that it became the best-selling car back then!

That Duesenberg prototype would have been interesting to see in the flesh.

Thank you, Mr. Exner for giving us your incite and taking the time to answer the questions. You and your father have given the automotive community untold measures of delight and usefulness, and we are indebted to you!

Thanks also to Hagerty Media for bringing this opportunity to us.

OMG – I’m sorry! Insight, not incite! Sheesh, is my face red!