Media | Articles

The Rise and Fall of Turin’s Design Firms

Italians are renowned for their obsessive attention to the aesthetics of pretty much everything. As a result, the country enjoys a reputation for style and flair that the marketing teams of brands like Alfa Romeo or Maserati waste no opportunity to exploit to their advantage.

Yet, few would argue that, when it comes to car design, that reputation was mainly established between the 1950s and the 1980s, the golden era of the Italian “Carrozzieri.” These were a handful of small firms located around Turin that, at the height of their creative powers, managed to exert an outsize influence on the aesthetic development of the automobile worldwide.

But it’s plain to see that those days are gone. Bertone is no more, ItalDesign is an outpost of VW, and if you want your new car to come with a Pininfarina badge, your only choice is the Battista hypercar.

So, what went wrong?

The question may be simple, yet the answer is anything but. The downfall of Italy’s famed design houses wasn’t triggered by a single event or circumstance. Instead, it was a gradual process characterized by multiple contributing factors. But to understand what knocked the likes of Pininfarina and Bertone off their perches, we first need to look at how they got there in the first place.

The postwar years weren’t kind to the European coachbuilding industry. The sector’s traditional client pool was dwindling, and as the continent’s automobile industry embraced unibody construction, so was the supply of suitable donor chassis to work on.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

By 1955, many prestigious Italian names from the pre-war era, such as Castagna and Stabilimenti Farina, were gone. The few coachbuilding firms that survived this tumultuous period were those with closer ties to the local automakers. These were the strongest, most resourceful outfits that could work with unibody structures and take care of small production runs—all while serving as actual design partners, too. Genuine one-stop shops that, on short notice, could ease the pressure from an automaker’s factory and design office.

That’s because while the switch to chassis-less construction made for lighter, more efficient cars, it also made tooling up for low-volume derivatives like coupès or convertibles significantly more expensive. And that’s where companies like Pininfarina and Bertone entered the picture. Outsourcing their design and production allowed Fiat, Lancia, and Alfa Romeo to offer sporting derivatives of their regular models without investing in additional production capacity. This became even more critical by the second half of the 1950s, as a booming Italian economy sent the demand for new cars through the roof.

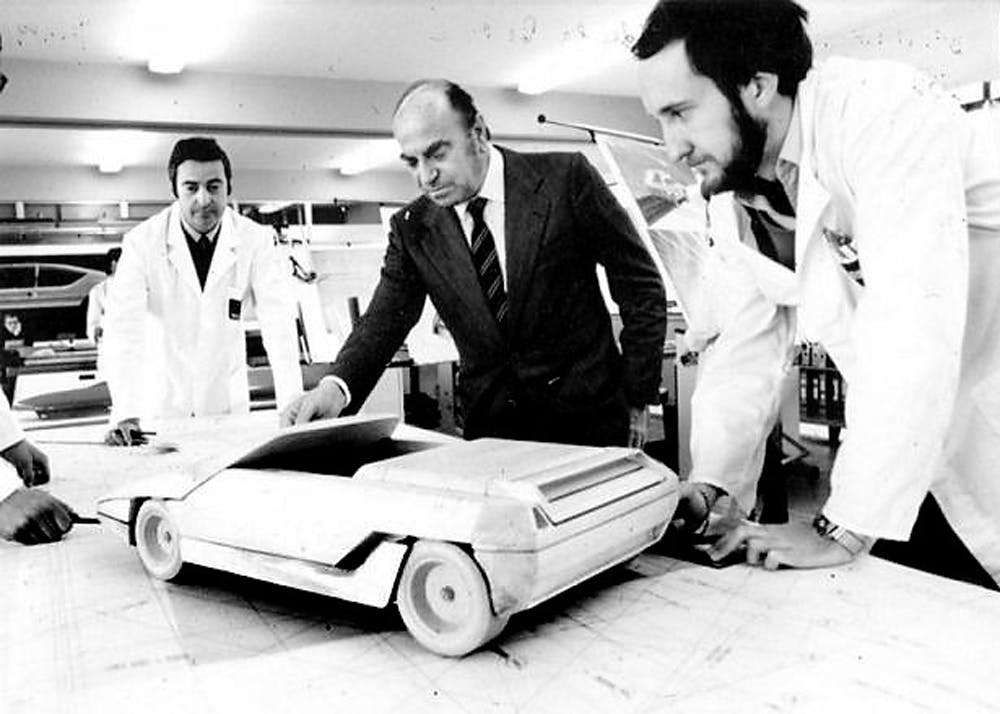

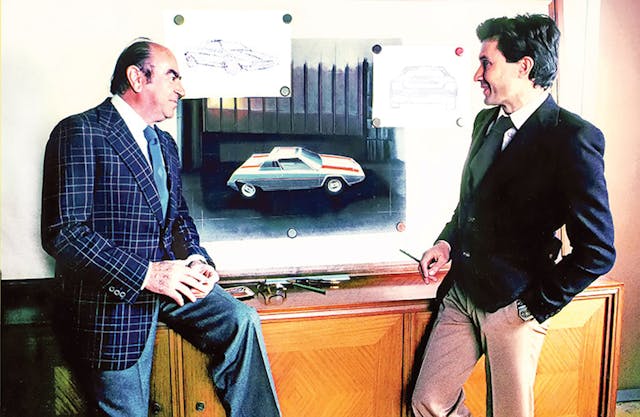

By the mid-’60s, these lucrative contract manufacturing arrangements had transformed Pininfarina and Bertone into small industrial empires. Both companies built car bodies by the thousands, yet their fortunes depended as much on ideas as they did on sheet metal. Being perceived as the cutting edge of automobile design was crucial to keep commissions coming in, so wowing the crowds at the Turin, Paris, or Geneva motor shows with sensational show cars was an integral part of these firms’ business. And the results were as spectacular as the cars themselves: Design commissions came pouring in from France to Japan and everywhere in between. It seemed the Turinese masters could do no wrong, but their success was due in no small part to favorable circumstances.

As we intend it today, car design was practically invented in Detroit in the late 1920s when GM established its “Art & Colour” section. It didn’t take long for each of the Big Three to have a well-funded and fully-staffed design department. But, strange as it may sound to our modern ears, during the ’50s and ’60s, most European automakers had yet to realize the essential role design played in market success. If they had an in-house design team, it was often understaffed and placed under the engineering department’s thumb. Management frequently had little understanding or appreciation for design matters and, lured by their flashy dream cars, didn’t think twice about handing the job to the Italians.

Of course, that’s not to say these people weren’t good. Unencumbered by the internal pressures the home teams were subjected to, the Italian studios repeatedly delivered the freshest, most original proposals. Sometimes, when one particular automaker was stuck in a dangerous creative rut, that outside input—think Giugiaro’s work for VW in the 1970s, for example—could even prove vital. But nothing lasts forever, and as the 1980s gave way to the 1990s, dark storm clouds were already looming on the horizon.

The first cracks began appearing right in the contract manufacturing business that had served Bertone and Pininfarina so well. Quality standards across the industry increased, while more advanced, flexible production methods allowed different cars to be made on the same line. As a result, automakers lost the incentive to outsource the production of lower-volume models. Moreover, if an international customer faltered, falling back on Fiat’s shoulders was no longer possible. Italy’s former industrial giant was all but broke heading into the turn of the new millennium and could no longer offer the support that had been so crucial four decades earlier. Few things can dig a larger hole in a company’s finances quicker than an idle factory, but the problems didn’t stop there.

By the time the last 747 full of Cadillac Allantés left Turin’s airport, design culture was much more widespread worldwide. Automotive executives were now acutely aware of design’s importance, and wanted to keep tighter control over it. Consequently, manufacturers invested heavily in their own design studios and often had multiple ones on different continents. With that, any incentive to involve third parties in the process was gone.

Especially when said third party counted most of your competitors among its customers. In an excellent biography published a few years ago, the legendary designer Ercole Spada shared a poignant anecdote from his time at BMW. He recalled how the company routinely asked each of Turin’s most prominent studios for proposals despite not intending to pursue any. But, since Pininfarina, Bertone, and ItalDesign all worked with BMW’s rivals, having these companies “compete” against its own design studio was, for the Bavarian firm, an indirect way to get a glimpse of its rivals’ general direction.

Last but certainly not least, complacency set in. There may still have been a space for Turin’s storied design firms in the modern era if they had kept their foot hard on the accelerator and their gaze locked on the horizon. Perhaps even more than in their 1960s heyday, being at the forefront of automobile design was a matter of life or death. Yet, one look at Bertone’s post-2000 output is enough to see why their phone stopped ringing.

Of course, Pininfarina is still around. Its latest work, the lovely Morgan Midsummer, shows that the company hasn’t lost its touch. But the days in which every Ferrari and every Peugeot on sale was a Pininfarina design are gone, never to return.

Nevertheless, it can be argued that what was created all those years ago in Turin continues to wield a certain influence on automobile design today. As a part of our shared cultural heritage, it’s in the back of every car designer’s mind, providing inspiration and being reinterpreted in novel ways. There are many examples out there, but the best one may be Hyundai’s brilliant Ioniq 5. It’s a resolutely contemporary and highly distinctive design, yet its design language’s roots are in Giugiaro’s “folded paper” cars from the 1970s.

Ultimately, the tale of Turin’s fallen design giants is as much about their amazing cars as it is about the fleeting nature of success. Left behind by the industry they once ruled, what’s left of the Italian “Carrozzieri” currently faces an uncertain future. What is certain, however, is that their massive legacy will stay with us for a very, very long time.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I could almost hear those Fiat 850’s rusting on the transporter lol

Lol! This is so true Mike. You are! Who? I’m sorry I don’t ping you in the park but lol

In those days American cars lasted longer because the gage of the Sheetmetal was thicker. Rust was not a consideration in designs

The glory days of Italian design. One can argue it has not been equaled since.

Since all manufacturers use the same design algorithm now, and it’s so important that everything looks the same, there’s no place for fresh and innovative design any more. Just make it bigger and it will sell!

Jellybeans!

@Matteo Licata , another welcome insight to this interesting era of Italian Design and Motorcars in general. The Spada/BMW anecdote was especially intriguing. Love these articles, keep them coming!

The keyword is: “economies of scale”.