Media | Articles

Tesla’s front-end styling tiptoes the line between stupid and clever

It’s such a fine line between stupid and clever. – David St. Hubbins

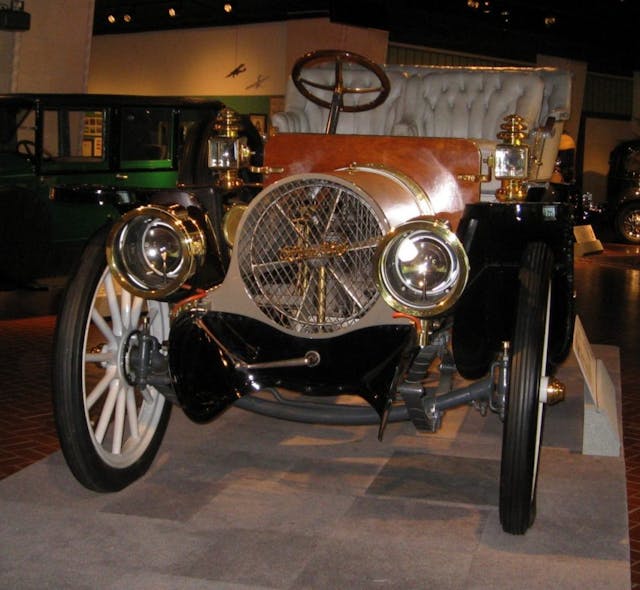

It’s not entirely clear which automaker was the first to turn a mechanical necessity—the radiator that keeps a water-cooled internal combustion engine from overheating—into a brand-identifying styling feature. The evolution makes sense, though, since the radiator sits at the front of car, in clean air, where everyone can see it. In short time, the actual radiators became enclosed in the bodywork, but the shapes of the radiators on luxury brands and mass-market offerings alike were so closely identified with those marques that the grilles that shielded the actual heat-exchangers adopted the radiators’ vestigial shapes. As many cars in the luxury sector had custom, coachbuilt bodies, the radiator grille became a critical styling element for early automakers to distinguish their products from those of their competitors.

Water-cooled cars weren’t the only automobiles to boast distinctive grilles, either. Franklin was probably the most successful air-cooled automobile in the first quarter of the 20th century, and its products were instantly identifiable thanks to the circular grille that fed the engine’s cooling fan and shrouds. As a matter of fact, Franklin’s chief engineer, John Wilkinson—a man of some accomplishment whose engine design is still being produced for light aircraft in Poland—even resigned in protest when the company, trying to save itself in the early ’20s, chose a conventionally styled grille. The Stanley Steamer didn’t have a grille, but the metal enclosing its boiler formed a characteristic, ventless snub nose. Even early Renaults, which were water-cooled but for some reason had their radiators placed behind the engine, up against the firewall, were easily identifiable head-on.

Early electric cars, though, were more nondescript. Combustion engines lose about 65 percent of their fuel’s energy to waste heat that must be managed with radiators. While modern EVs have sophisticated battery-management systems that use either liquid coolant or air to ensure optimal performance, maximum life, and safe charging, they don’t depend on a large, front grille. Perhaps that’s why prewar aficionados can immediately tell a 1914 Rolls-Royce from a 1914 Packard, but must squint to tell a Detroit Electric from a Baker or a Rauch & Lang of the same vintage.

When electric cars re-entered the mainstream in the 21st century, several wore fake grilles—perhaps to ease consumer acceptance, or because they’re simply considered an essential part of automotive styling. The 2010 Nissan Leaf included an air dam in its lower bumper, below the conspicuous charging port on its nose. The first-generation Model S had a large, gloss-black panel that reminded me so much of the Maserati Quattroporte’s that I mentioned it to Tesla design head Franz von Holzhausen at the Detroit Auto Show.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

“Maserati?” I said, pointing at the Model S’s nose. Franz grinned widely, saying, “I don’t know what you’re talking about. They’re completely different shapes … but it never hurts for people to think your design looks expensive.”

“Franz,” I replied, “it’s true, they have different geometrical shapes—but guys like you get paid to make guys like me make the association without it being too obvious.”

The second-generation Model S eliminated that black faux grille, replacing it with a flat, body-colored panel topped by a minimalist grille, a slender T-shaped opening that echoes Tesla’s logo. The Model X CUV debuted with the same face. I personally think that grille design is brilliant. It’s instantly identifiable and immediately associated with the California-based company.

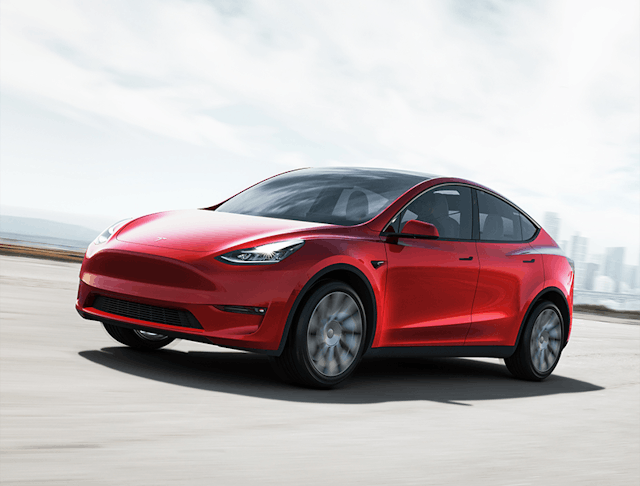

When I first saw photos of the production Model 3, I was disappointed. I was even more dismayed when I saw the cars on the road: The minimalist grille was gone, replaced with an expanse of nearly featureless metal. Von Holzhausen may have attempted to make the original Model S evoke Italian luxury, but the Model 3 looked like a cheap, injection-molded plastic toy. Well, at least the front end did. The rest of the car is smartly styled. The same generic front end also appears on the Model Y crossover, a car that may be even more critical to Tesla’s success than the Model 3 sedan.

Here’s the thing, though. While I’m not the only person who thinks this way about the Model 3’s styling, that hasn’t affected sales of the EV. Introduced in 2018, Tesla sold over 400,000 of these compact sedans last year and over 800,000 in total so far. By contemporary automotive industry standards, the Model 3 is a smash hit.

Am I out of touch with car consumers? Perhaps, or maybe von Holzhausen’s team has managed to stay on the clever, rather than the stupid side of that fine line. As nondescript as the Model 3 and Model Y “grilles” may be, the cars are instantly identifiable. You may think it handsome—I may think it bland and cheap—but, with a single glance, we both know exactly what it is: a Tesla.