Media | Articles

Marcello Gandini Drove a Renaissance in Automotive Design

When discussing the halcyon days of Italian automobile design, I don’t hesitate to define the years between 1950 and 1980 as Italy’s second Renaissance. That may seem like hyperbole, but it’s a more fitting analogy than your art history teacher might like to admit.

Much like 15th-century Florence, a unique set of circumstances in the mid-20th century turned Turin into a hub of intense creativity. This time, however, at the heart of this creative explosion was not literature or the arts, but the quintessential product of the industrial era: the automobile.

Like Florence under the Medicis, the golden era of Turinese coachbuilding saw the work of countless artists and craftsmen eclipsed by the towering achievements of a handful of legendary masters. And masters don’t get much greater than Marcello Gandini, who passed away on March 13 at 85.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

As it’s widely known, Gandini was hired by Nuccio Bertone in 1965 following Giorgetto Giugiaro’s move to Ghia. Mr. Bertone had a keen eye for talent, but probably even he couldn’t imagine just how good his decision would turn out to be.

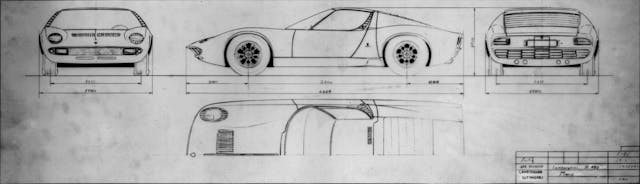

Gandini’s first project for Bertone was the car his name will forever be associated with: the Lamborghini Miura. Widely considered among the most beautiful cars ever made, the Miura’s design was a masterful synthesis of different influences. Its overall concept drew heavily from Ford’s GT40, while the surface treatment and detailing owed much to previous Bertone designs from Giugiaro, particularly the 1963 Corvair Testudo.

Although its mechanical layout was inspired by motorsport, in the Miura, function definitely followed form. It was the fastest car money could buy, but its capabilities as a vehicle were entirely secondary to visual drama. Designed primarily to drop jaws rather than seconds off a lap time, the Miura marked the birth of the bedroom poster supercar. Yet, while the rest of the world was busy writing checks to Lamborghini, Marcello Gandini had already moved on.

The Miura had boosted Bertone’s reputation to unprecedented heights, much to the dismay of its crosstown rival, Pininfarina. But there was no time to rest on one’s laurels—these firms’ thriving yet fragile business model hinged entirely on being perceived as the bleeding edge of automobile design. With that precious reputation on the line at every year’s major motor show, it was a case of innovate or die. And innovate Gandini did, big time.

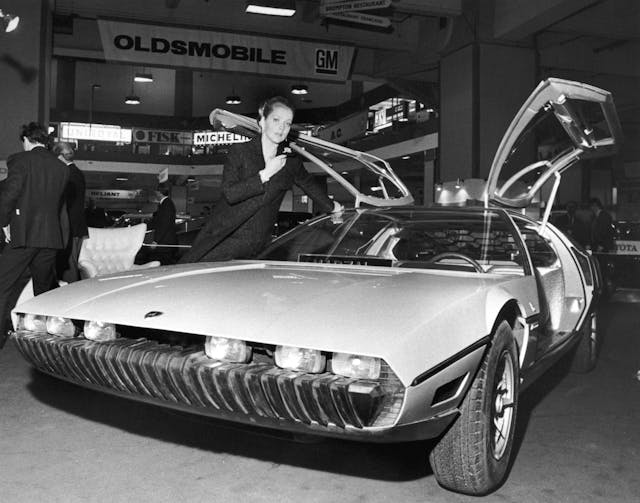

First came the Lamborghini Marzàl, which landed at the 1967 Geneva Motor Show. The word “landed” is entirely appropriate, because few other artifacts embody the era’s fascination with space exploration quite like the Marzàl. Built on a lengthened and extensively modified Miura chassis, the Marzàl was a piece of art inside and out.

Its front end was a slim black slit, housing six Marchal quartz-iodine headlamp units, among the smallest available at the time. The Marzàl’s giant glass gullwing doors exposed its four passengers like mannequins in a shop window, while the mechanical elements remained hidden under a matte black, three-dimensional hexagonal pattern engine cover that looked like armor plates.

The hexagonal honeycomb theme continued in the dashboard’s instruments and controls, as well as the seat cushions and backrests, which were upholstered in a highly reflective silvery material reminiscent of a spacesuit. If Gandini’s initial works for Bertone still had a tinge of Giugiaro’s design influence, the Marzàl was the turning point at which Gandini broke away from that mold and never looked back.

When the 1968 Paris Motor Show doors opened, the Miura was less than two years old and still the hottest thing on four wheels. Yet, that didn’t stop Gandini from completely rewriting the design template for the whole supercar genre.

Based on an Alfa Romeo 33 Stradale chassis and running gear, the Bertone Carabo was a radical departure not only from established aesthetic norms but also from anything Gandini had done until then.

Inspired by the latest trends in racing car design, the Carabo was as pure a “wedge” shape as possible, achieving a low drag coefficient while minimizing the front-end lift issues that plagued the Miura. Gandini took advantage of the relative absence of mechanical hardpoints at the front of the Alfa 33 chassis to keep the Carabo’s nose low and frontal area to a minimum.

Thus, the Carabo’s visual weight was concentrated at the rear. Its profile was characterized by a single, nearly unbroken line from nose to tail, as the flat bonnet merged seamlessly with the windscreen. Gone were the Miura’s sensuous curves, replaced by sheer surfaces with minimal crowning and tight radiuses: it was the dawn of the “folded paper” design language that would dominate 1970s automobile design.

Nowadays, Franco Scaglione’s curvaceous 33 Stradale is rightfully revered as a design masterpiece. But one glance at Gandini’s creation, based on the same underpinnings, is enough to realize just how far he was pushing the envelope.

The Carabo was never meant to become a production car. Yet, in a roundabout way, it did. That’s because when it came time to design the Miura’s replacement, Marcello Gandini reused the same essential design ingredients (scissor doors included) but distilled them to even greater effect. Leaner, sharper, and with even more dramatic proportions than the Carabo due to its bulkier powertrain, the Lamborghini Countach hasn’t lost an ounce of its visual impact over half a century from its conception.

Marcello Gandini remained at Bertone until 1980. His early years as the Turinese firm’s main creative force were not only the company’s finest hour, but arguably the period in which Italian car design reached its peak in terms of international influence.

Over the following years, from a desk in his country house outside Turin, Gandini tackled everything from massive industrial programs for Renault to underfunded supercar projects like the Cizeta Moroder. Though not all the entries in his vast back catalog can be considered masterpieces, each of his efforts affirmed Gandini’s unwavering commitment to technological and aesthetic innovation.

That’s a commitment Gandini reiterated in what would turn out to be his last public appearance. In the speech he gave before receiving an honorary degree in engineering from Turin’s Polytechnic University this past January, he urged the young students to “extract from limitations and impositions a strong, stubborn, and constructive sense of rebellion.”

Addio Maestro, e grazie di tutto. Non ti dimenticheremo.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Probably the most talented car designer of all time.

There is some dispute over the design credits for the Miura. It may have been mostly designed by Guigaro but finalized by Gandini.

It is a shame that the Countach picture selected is not of the original show car which most demonstrates Gandini’s purest design.

Although Gandini’s work was spectacular, Guigaro’s Ital Design was more influential across the worldwide auto industry during the last half of the 1970s and into the 1980s. He was the master of the “folded paper” idiom.

So many great designs, many that never saw production. He will be missed.

You used a photo of a Countach 25th Anniversary model as an example of a Gandini design? Because it’s not…it is an extremely unfortunate revision.