Media | Articles

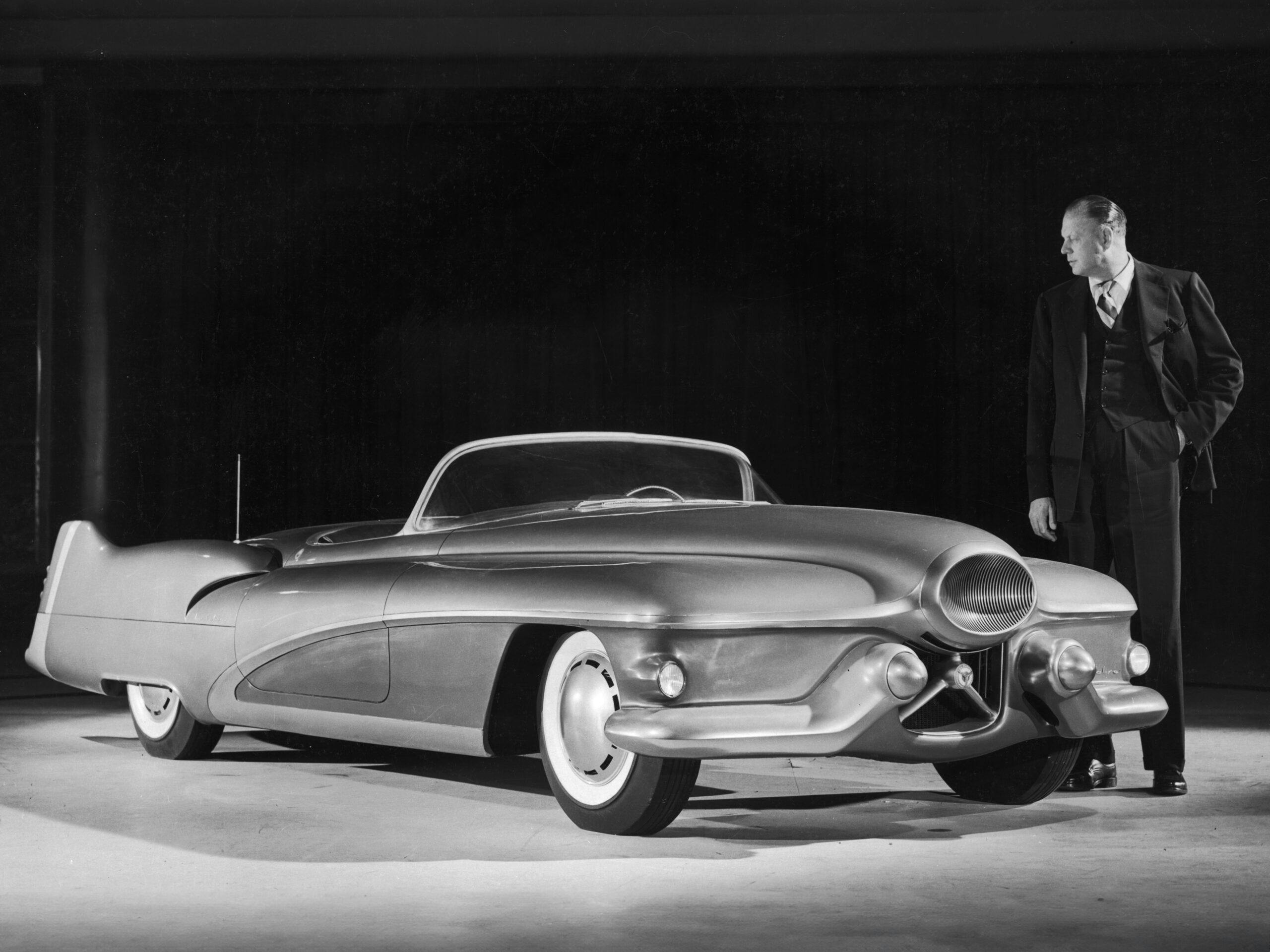

How the 1951 GM Le Sabre Concept Forever Changed Car Design

Like many beautiful things in life, concept cars are ephemeral. These are vehicles built to showcase a company’s creative and technological prowess, at the expense of permanence and production reality. Like shooting stars, they shine bright and captivate our attention for a fleeting moment, only to vanish into the night sky as quickly as they appeared.

But, as always, there are exceptions. Concept cars can prove so influential that they become genuine landmarks in the aesthetic evolution of the automobile. Precious few designs belong to this exclusive club; GM’s 1951 Le Sabre is undoubtedly among them.

The story of the Le Sabre begins with the car it was meant to replace, the seminal Buick Y-Job from 1938. That one-off roadster is widely considered the first concept car ever created and served as GM Design Vice President Harley Earl’s personal car for over a decade. By 1947, though, the Y-Job no longer looked as fresh as it once did, and Earl began thinking about a replacement.

Harley Earl proposed that Buick’s chief engineer, Charles Chayne, create a pair of two-seater convertibles built on identical chassis but wearing two different, futuristic bodies. The rationale was to show off GM’s leadership in automobile styling and engineering. Naturally, Earl and Chayne would get one car each for personal use.

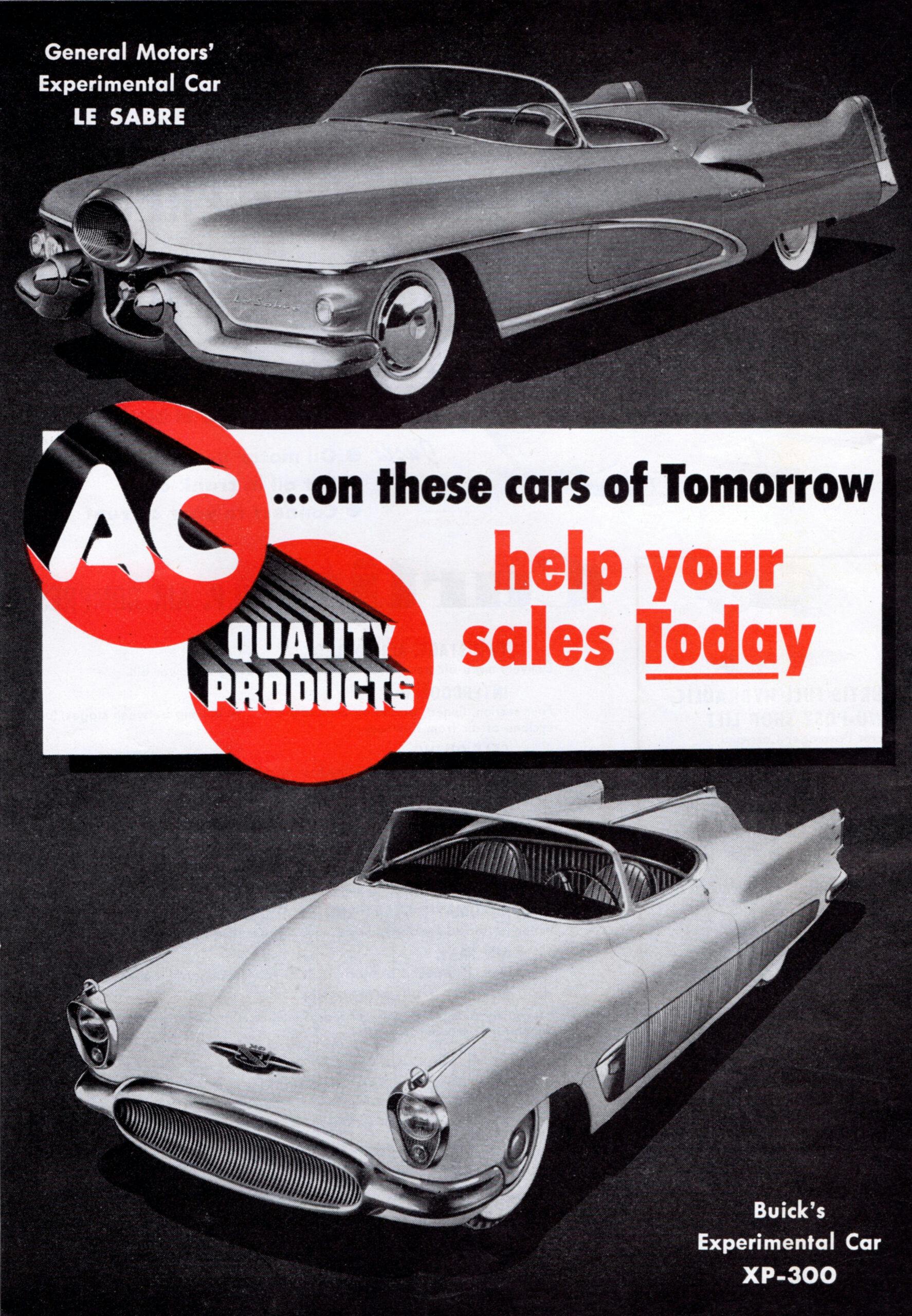

Development work on the two cars began in 1947 under the XP-8 and XP-9 codenames. Both saw the light of day in 1951. However, while the XP-9 (rechristened XP-300 upon its unveiling) soon faded from public memory, the XP-8 became an all-time icon: Earl’s legendary Le Sabre.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The name was a nod to the military aircraft that inspired the car’s design, the North American F-86 Sabre. The first prototype of this jet fighter flew in 1947, and it’s easy to see why it caught Harley Earl’s imagination. With its smooth, sleek fuselage and its wings dramatically swept back to reduce drag as it flew close to the sound barrier, the F-86 Sabre was a direct byproduct of the massive strides made by aviation technology over the war years. The F-86 embodied speed and progress, and Harley Earl aimed to bring those values down from the sky to America’s roads.

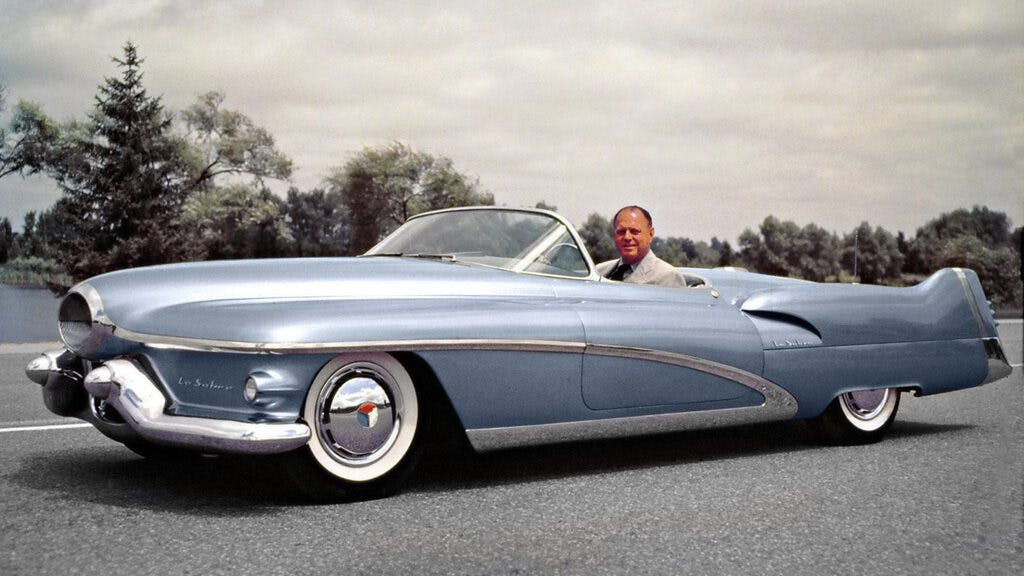

Earl knew well that beauty in car design is, above all, a matter of proportions. From the time he joined GM in 1927, the man relentlessly strived to make the corporation’s cars as long and low as possible. With an overall length of over 17 feet and a height of just 58 inches, the Y-Job already epitomized this ideal, but the Le Sabre went a step further. It wasn’t any longer than the Y-Job but was just 50 inches tall: 2.5 fewer than a Jaguar XK 120 and about 15 fewer than an average car from the period.

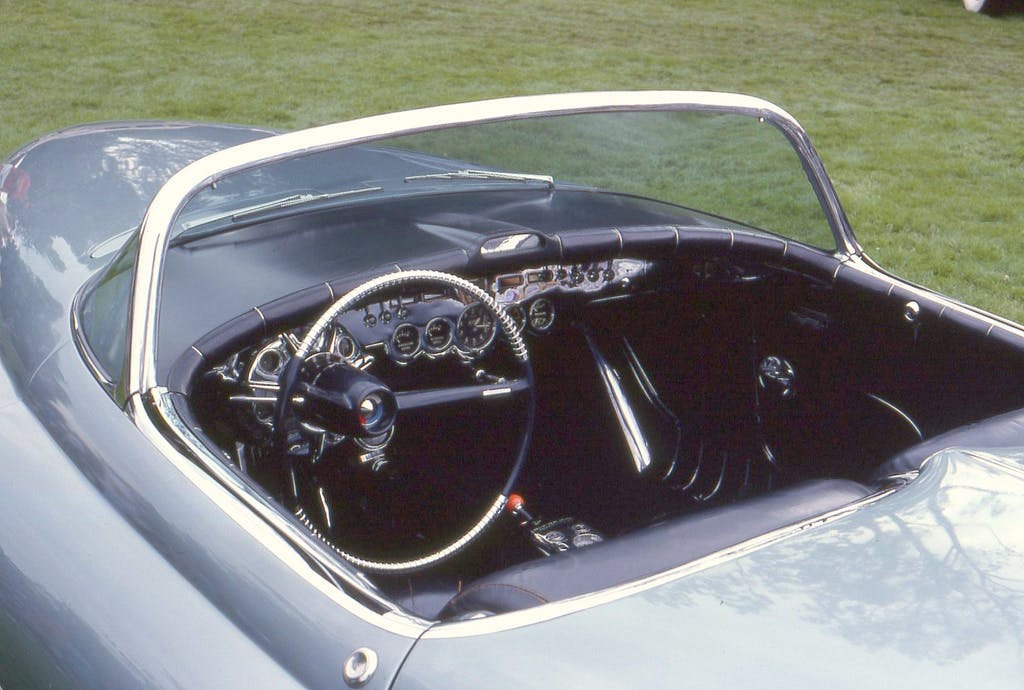

The Le Sabre’s front end was dominated by a giant oval grille; it was meant to evoke the jet’s air intake but served a very different purpose. Back then, the limitations of lighting technology meant designers could hardly do anything about headlights. Saddled with elements whose shape and dimensions couldn’t be altered, automotive stylists spent decades either working around the headlights or concealing them in ever-more inventive ways to give the car an enigmatic “eyeless” look. Since jet fighters have no headlights, GM’s stylists hid them into the Le Sabre’s faux air intake, behind grilles that retracted at the flip of a switch.

Aviation influences informed every facet of the Le Sabre’s design. Its body was built from lightweight cast magnesium parts and hand-formed aluminum panels, all expertly crafted to seamlessly fit together like an aircraft’s skin. The convertible top, which could operate automatically thanks to a rain sensor, folded neatly out of sight under a flush cover. Rather than being treated as accessories, the bumpers, grille, and all trim pieces were made to blend into the car’s body and form a cohesive whole. The Le Sabre’s rear deck tapered into a single, large circular opening which, once the sizeable red taillight inside it illuminated, was meant to resemble a lit afterburner. Tall, prominent tailfins, each housing a bladder-type fuel tank inside, completed the package.

By then, tailfins weren’t a new idea. Inspired by the Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter aircraft’s twin-boom design, tailfins famously made their debut on the 1948 Cadillac. However, those still were relatively subdued affairs, unlike those of the Le Sabre. Unapologetically tall and prominent, the Le Sabre’s tailfins spearheaded the ever more flamboyant interpretations of this design feature hailing from Detroit’s design studios throughout the 1950s.

Inspired by the teardrop-shaped transparent canopies of jet fighters, the Le Sabre also featured a wraparound “panoramic” windscreen. Harley Earl had toyed with the idea for decades, but only at the dawn of the 1950s was the technology to make such sharply curved glazing finally perfected. Made by laying semi-molten glass over a steel form and having the ends draped down by gravity, panoramic windscreens first went into series production at GM in 1953, and within a couple of years, Ford and Chrysler had them, too.

With the establishment of Harley Earl’s “Art & Color” section in 1927, General Motors practically invented automobile design as practiced today. That leadership played a fundamental role in the corporation’s rise toward market dominance over the following years. And, by the time the Le Sabre was unveiled, GM’s huge market share meant its every move had ripple effects across the industry. That was especially true when it came to styling, and the public’s raucous reaction to the Le Sabre’s flamboyant design reaffirmed GM’s position as the car industry’s tastemaker and brought Detroit’s automobiles into the jet age.

Moreover, the success of the Le Sabre got the public to crave more dream cars like it. This led to Earl’s team providing GM’s Motorama exhibitions with a continuous stream of increasingly extravagant concept cars, starting in 1953. This further solidified GM’s position as a leader in automotive design and exerted a powerful influence not just on its Detroit rivals’ output, but also across the Atlantic.

In the Western European countries recovering from the ashes of WWII, everything that came from America held huge appeal. The music, pop culture, and flashy automobiles from the U.S. embodied the promise of a better future in the eyes of people who wanted nothing more. Consequently, it took little time for tailfins, panoramic windscreens, and other jet-inspired design flourishes to crop up in the Paris, London, or Turin motor shows.

Thanks to its role as Harley Earl’s preferred choice of wheels, the Le Sabre has never been at risk of being discarded and destroyed, even after it no longer looked like the future. Lovingly restored in the 2000s, today the Le Sabre is among the crown jewels of GM’s Heritage collection, and rightfully so. It represents post-war America’s hopes and dreams better than any historical treatise ever could, and may well be the single most influential design ever to come out of GM’s studios.

Not bad for what began as the design boss’s new company car.

***

Matteo Licata received his degree in Transportation Design from Turin’s IED (Istituto Europeo di Design) in 2006. He worked as an automobile designer for about a decade, including a stint in the then-Fiat Group’s Turin design studio, during which his proposal for the interior of the 2010–20 Alfa Romeo Giulietta was selected for production. He next joined Changan’s European design studio in Turin and then EDAG in Barcelona, Spain. Licata currently teaches automobile design history to the Transportation Design bachelor students of IAAD (Istituto di Arte Applicata e Design) in Turin.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Actually GM nearly scrapped the Le sabre and the Y job. Both were lasted for destruction in the early 70’s and save by a group a the tech center.

The folks at the Tech center saved a number of cars.

Bill Mitchell kept a number of the show cars at his home after he retired and they better appreciated them by the time they were returned after his death.

GM’s historic collection is missing a number of cars due to bad calls but thanks to others they were saved.

The Y and Le Sabre were both land mark cars that really set the future in many ways. Thile being futuristic Earl still kept them to be somewhat realistic. He made them a showcase of ideas he was going to bring to market.

I was a 60s kid in grade school… when field trips were actually something. We went to the Ford Rouge Plant and got “sparkled” when they were casting engines….Went to the Kellogg’s plant in Battle Creek and scooped Frosted Flakes off the production line…. went to the GM Tech Center and saw all the amazing cars and dreams. I remember seeing this very vehicle and several others…… sadly…. kids will never experience this American Dream………..

It’s pretty amazing that a concept car could be built with many of the futuristic innovations actually functional and still be usable regularly on the street. Technology has evolved so far that to attempt to do that now would likely be cost prohibitive, which is why modern concepts are often just composite shells with interiors but no ability to drive. Or they are fairly close to near-future production cars but don’t have any particularly futuristic tech under the skin.

Great looking car wish they made them today for real not concept

Harley liked them low and was pushing for the lowered look in the 30’s

The Le Sabre kind of looks like the car in the Johnny Cash song “One piece at a time”. TOO many concepts in 1 package. The XP300 was a nicely done car that might have sold

There are a lot more future Buick themes in the XP300: grille–1954; headlight/parking light surrounds 52-55; hood shape and wide Buick logo, 51-54; and the wrap around windshield (’53 Skylark), than the Le Sabre predicts for future Cadillacs–through-the-rear-bumper exhaust tips excepted.

So many bits of info about features of the car are missing in this article… the ENGINE for example. An aluminum block 215 cubic inch V-8 that would appear 10 years later in Buick and Oldsmobile compact cars. Correctly noted in the article, this concept car was NOT commissioned by Buick, it was a GM LeSabre, not a Buick LeSabre. The dual fuel tanks were independent because one was for methanol and the other was for gasoline. I am not sure where you got a tankful of methanol in the early 1950s. As with ethanol, methanol can produce more horsepower than gasoline, but each gallon of alcohol contains less energy than gasoline, so mpg would suffer while operating on methanol, but power would be a little better. There is no visible cut-line for the hood. The polished stainless trim along each fender and wrapping around the front of the hood hides the cut-line completely.

It’s not my favorite but it is interesting to look at.

I wish that Earl hadn’t later updated the Le-Sabre with the heavy metal trim on the sides. The photo with Earl sitting in the car in it’s original form shows the car had a very sleek uncluttered look. Alas, hordes of chrome took precedent in the later 50s so the car got the treatment.

That’s one ulg car it looks just like a Ford Edsel both of them are ugly le saber

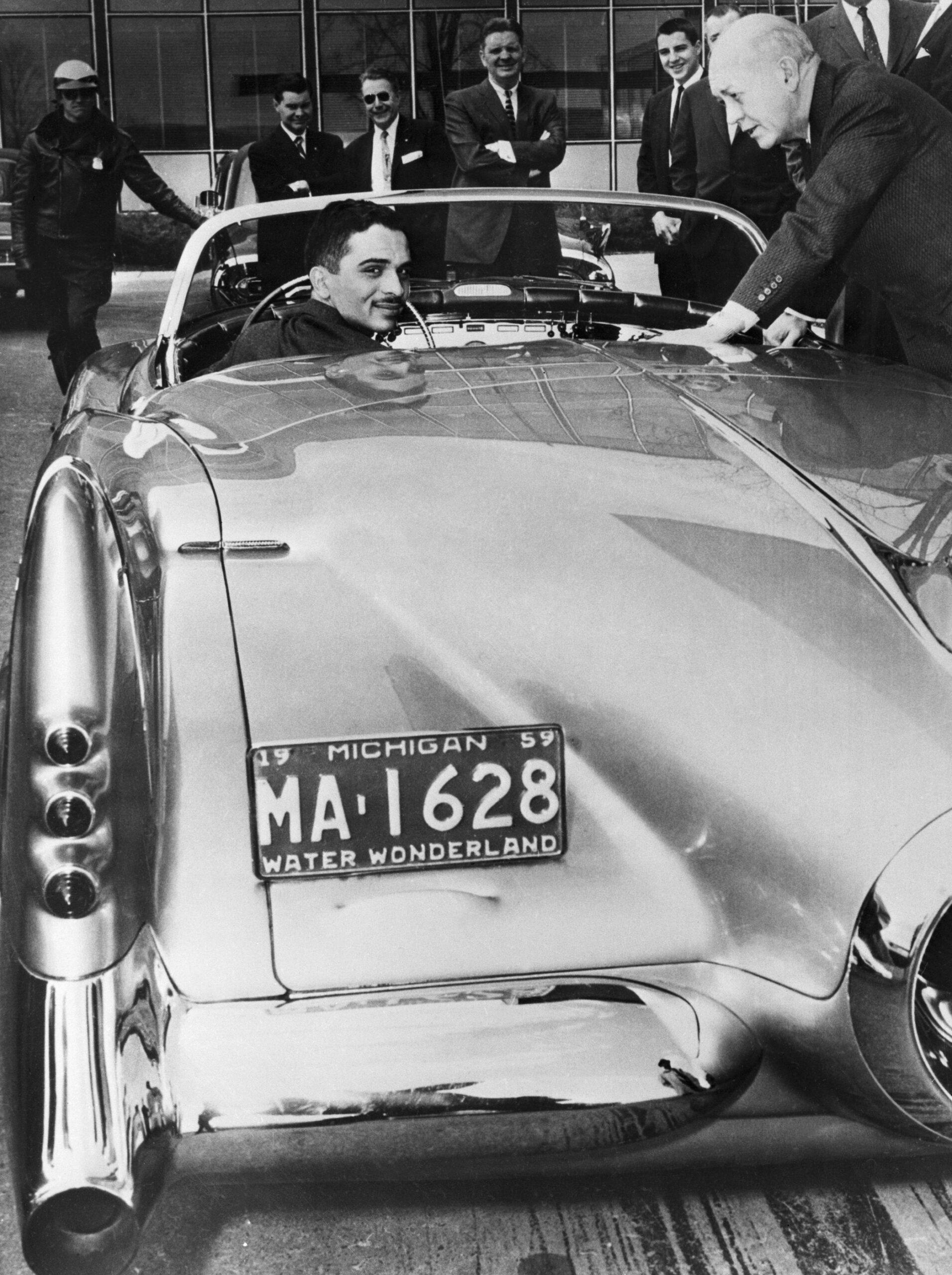

It appears that when the additional brightwork was added fender vents were integrated into the front fenders. It seems to me the Police Officer in the photo above is not very impressed.