Media | Articles

Car Design Fundamentals: The A-pillar

Now that we’ve covered how cars are designed, it’s time to review some of the terms designers use when talking about car design. Some of these words and phrases are referenced on a regular basis, even if they seem rather obscure. With that in mind, consider this your go-to reference series for car design lingo. Today’s lesson: The A-pillar.

The A-pillar is one of the most important design elements that determine a modern vehicle’s shape. Or as designers call it, its volume. We’ve already looked at dash to axle and its impact on a car’s powertrain and market segment. The A-pillar, its location, and its angle play an important part in defining not only the dash to axle ratio, but the entire shape of a car’s front end.

The A-pillar is the structural upright that partially frames the windshield. A-pillars (one on each side of the body) are joined across the top of the windshield by the header rail. The base of the windshield where it meets the hood is called the cowl. The portion of the roof that joins the A-, B-, and C-pillars together to form the vehicle’s roof structure is known as the “cant rail.”

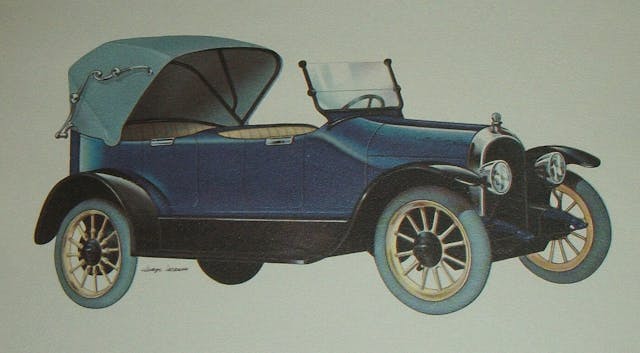

Studying these pillars and rails can tell us a lot about the evolution of vehicle design. By the mid-1920s, cars were beginning to appear with fully enclosed bodywork. Before that, if you were lucky, you got a sheet of glass bolted to the front of your car and a flimsy canvas canopy as the sum total of your protection from the elements. (Crash regulations, of course, hadn’t been implemented yet.)

Automobile construction moved from traditional “horse and buggy” methods and towards monocoques and body-on-frame by the 1930s. This evolution meant the pillars of the car’s roof became an integral part of framing the glass, essentially tying the roof to the rest of the bodywork. This meant the A-pillar bore a bigger burden, as it was the part of roof that interacted with the business end of an automobile.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

So how does this critical piece of a car’s structure relate to dash to axle? Put simply, dash to axle revolves around the A-pillar’s position, and where the A-pillar points to if you extend its trajectory past the cowl.

On front-wheel-drive cars, CUVs based on said front-drive platforms, and most mid-engine exotics, if one continues the line from the A-pillar toward the ground it will pass in front of the front axle’s centerline:

Pulling the A-pillar forward increases passenger room and moves the header rail farther away from the occupants’ heads. While important for crash regulations, this decreases the angle between the windshield and the hood, effectively reducing the visual separation between these two parts, giving you a one-box shape known as a monovolume.

Most modern subcompacts and compact-sized cars (Euro B & C class) are almost this shape, although having a long A-pillar heading toward the front of the car can cause blind spots—not exactly what you want in a commuter vehicle. On the Prius pictured above, it looks more aerodynamic because of its shape, but it’s really an illusion (because gas mileage is a big part of the Prius’ appeal). Aerodynamics is affected more by things like frontal area, flushness of fittings, and a vehicle’s overall length.

On rear-wheel-drive cars and larger SUVs, the A-pillar’s line will point straight through or slightly behind the front axle’s centerline.

Moving the A-pillar rearwards gives you a better hood definition, better windshield definition, and creates a wider field of view, but it now encroaches into passenger space. When defining the angle of the pillars (and hence the vertical height of the windshield) particular care needs to be taken to ensure that vertical vision angles are not compromised: a downwards vision angle of less than 6 degrees will give shorter drivers problems seeing the end of the bonnet and an upwards vision angle of less than 11 degrees means you’re looking through the header rail. At 6’2” I have this problem in my Audi TT; I sometimes have to duck down to see high-mounted stop lights when stationary, because the header rail is so low.

Despite Tesla claiming the Model X is an authentic SUV, in reality its volume and ride height mean it’s closer to that of a CUV or minivan. The A-pillars’ location contribute to its vast passenger cabin, and the cowl height (and lack of an internal-combustion engine) mean there’s room for a useful frunk.

For those who long for the days of thin, wispy A-pillars, you have roof crush legislation to thank for the increased thickness. Since 2009, enclosed passenger vehicles must be able to withstand three times the weight of the vehicle being applied to the roof, without harming the occupants. Coupled with the fact that the A-pillar on a modern car also contains an airbag, wiring loom, and padded trim pieces, you can see why they are getting so chunky.

Way back in 2001 Volvo—always ahead of the game on safety—debuted the SCC Concept at the Detroit Auto Show. As well as previewing many of the electronic safety systems we now take for granted, the concept featured see-through A-pillars.

Unfortunately these were a step too far, and the production version of the SCC appeared as the conventionally-pillared Volvo C30 hatchback.

In the future we may have cars equipped with yet another electronic safety aid: the transparent A-pillar. Jaguar Land Rover is working on it, and in 2019 a teenager won a $25,000 science prize for using a webcam mounted outside of the vehicle to feed images projected inside the car onto the A-pillar.

As mentioned earlier, the pillars of a car help to describe its overall shape. Next time we’ll look at their relationship with each other, and why the C-pillar is so critical in making a car look right.