Media | Articles

When the world’s greatest architects met a Hyundai EV

Across the digital world, most published content is bite-size, designed for quick consumption. Still, deeper stories have a place—to share the breadth of an experience, explore a corner of history, or ponder a question that truly engages the goopy mass between your ears. Pour your beverage of choice and join us for a Great Read. Want more? Have suggestions? Let us know what you think in the comments or by email: editor@hagerty.com

For some, comparing automotive design and architecture is like mixing oil and coolant: two necessary parts of life that should never intersect.

Humankind’s need for impressive buildings, however, parallels its desire for an eye-catching automobile, as both are byproducts of Modernism. Appeal in each is hung on texture, shape, proportioning, and the ambient interplay of light and shadow. At the same time, the relationship between an architect and the needs of a growing city produces the same kind of passion, success, and failure as any automotive styling studio.

Columbus, Indiana, is one of the few American cities to use a modernist aesthetic as both historic foundation and inspiration for future growth. And if there’s one time in history when car designers have the freedom to make an impact at the scale of a growing city, it’s now.

And so began my idea to engage in a sort of cinematic journey through the concept of Modernism, driving a car of similar ideals. But which car?

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

It had to be an EV. The simple chassis architecture and seemingly endless development funding of an electric vehicle allow for the creation of genuinely new shapes. Teslas are widely popular, but their lines are stuck in the late 2000s. The EV platforms from most other automakers aren’t much better, with their slapped-on light bars and hastily grafted corporate DNA. Only Hyundai looks forward while paying homage to the past.

In this case, “past” means a minimalist wedge—sourced from legendary designer Giorgetto Giugiaro, no less—that helped put the company on the global stage in the 1970s. The Hyundai Pony was never sold in America, but it’s a big deal in Hyundai design circles. And that’s why I chose the Hyundai Ioniq 5 for this trip.

It may seem far-fetched to line up the architectural traditions of a midwestern city with the corporate styling aspirations of a South Korean juggernaut, but spending a week with the car along the progressively modernist streets of Columbus made one thing clear: good things happen when people, planning, and bold aspirations for the future converge.

***

Let’s first discuss our host city, once home to a wealthy industrialist named J. Irwin Miller. The World War II veteran had a penchant for modern design, thanks partly to having studied at Yale. But personal interest blossomed into something special. Miller’s great uncle, William Irwin, co-founded the Columbus-based Cummins Engine Company, the famous maker of diesels. Miller joined the family business in the 1930s, rising to chairman after the war. Foreseeing a need to both entice and retain the top talent that would help Cummins grow, he envisioned a city with inspired schools, forward-thinking churches, and stunning public buildings.

In 1957, that vision manifested in the Cummins Foundation. The charitable arm of the powertrain powerhouse offered architectural grants on behalf of the city of Columbus, paying for famous mid-century architects to create masterworks in town.

This work had significant impact. Columbus became both a testament to the power of design and a travel hot spot for architecture fans. Tours buses now circle the city at regular intervals, showing off the work of architects like I.M. Pei, Kevin Roche, and Eero Saarinen. McMansions and strip malls later blossomed in the suburbs, but the region worked to preserve its heritage and remains inspiring today.

Columbus wasn’t built in a day, however, and it took more than 50 years for Hyundai to arrive at the Ioniq 5. Much as cookie-cutter architecture fueled America’s mid-century growth, Hyundai spent its early years building other manufacturers’ vehicles under license. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the company gained the fortitude to engineer its own products.

Hyundai’s managers wisely realized that the young firm remained ill-equipped to style those cars for the global market. That’s where Pony enters the scene, making its formal debut in 1974. Further Italian commissions like the Excel, the Stellar, and the Sonata were clean and logically styled, and they gave the brand compelling showrooms. By 1990, increasing market share had justified the creation of Hyundai’s own, California-based, styling studio.

Still, even the most elegant compact car can be seen as disposable. Significant achievement eluded the brand until recent decades, when it began to prioritize larger vehicles and with unique and refined details. And much as how Hyundai once recruited Austin-Morris executive George Turnbull to get Pony production off on the right foot, the company’s latest styling crop came under the tutelage of design vice president SangYup Lee, who was cherry-picked from Bentley.

A dedicated EV platform can force a change in how you make cars. The Ioniq 5, the first vehicle from Hyundai’s E-GMP electric platform, was launched in 2022. It is a four-door, five-passenger crossover with fast-charge capability, available in either rear-wheel-drive (single-motor) or all-wheel-drive (dual-motor) configuration. The entry model, around $49,000, gives 168 hp and 220 miles of range.

Our test car, a top-of-the-line, all-wheel-drive Limited model borrowed from Hyundai, produced 320 hp and carried a base price of more than $57,000. You can see a little Pony in the Ioniq 5’s detailing, and the C-pillar heavily recalls Chrysler’s 1980s Omni / Horizon compacts. No matter: This car looks like nothing else on the road, and like no Hyundai before.

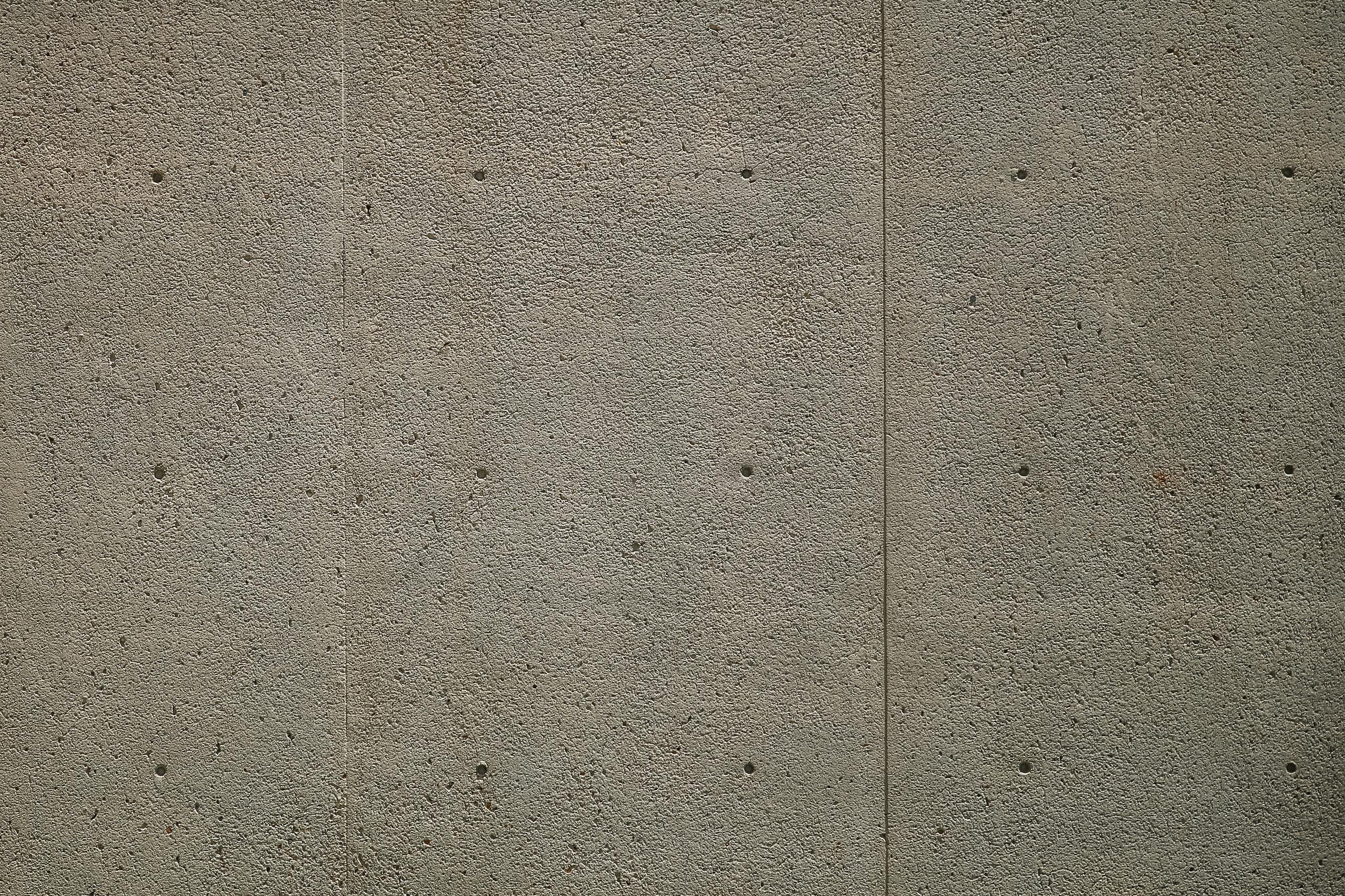

EVs and revolutionary styling can each prompt admiration and controversy, which is why our Columbus tour first stopped at Southside Elementary. This school, designed by Eliot Noyes and built in 1969, is the city’s best example of Brutalist architecture, a style that utilizes the flexibility of poured concrete to create buildings in almost any shape. Brutalism allowed engineering creativity in an era of staid reconstruction after World War II: Radical textures replaced attention-grabbing ornamentation, and right angles became a feature, not a byproduct.

Few architectural styles are as mired in controversy. While the name suggests a purposeful crudity, Brutalism is derived from the French words beton brut, raw concrete. Like an EV trying to make a name for itself, the style is more polarizing than a presidential election. Where the school has windows, they are recessed in concrete, visually demoted by Brutalism’s hallmark radical shapes and proportions. The Ioniq 5’s inescapable angular door slashes strike the same tone as Southside’s imposing and top-heavy façade—they do a fantastic job of hiding the car’s size and substantial wheelbase. (At 118 inches, the Hyundai has more space between its hubs than a Lincoln Town Car.)

Brutalism can be difficult to process, but the details are the reward. Peek inside the initially incomprehensible space holding Southside’s entryway and second-floor hallway, you get a set of stairs seemingly formed from a single slab of concrete. Richly textured gray walls are contrasted by bright artwork hung on the back wall. Within the staircase itself, the skylight in that soaring ceiling forces sunlight to become another geometric element.

These shapes take work to understand, and they challenge the viewer’s notions of how a building should be designed. Look, too, how the Ioniq 5 sports a strong shoulder line below its glass. Follow that line down the body side, it becomes a triangular form reminiscent of a flint arrowhead, slicing deep into the coachwork. As the quarter panel juts aft and into the car’s hatchback rear, a bewildering number of flat planes, curved panels, straight lines, and finger-size squares mirror Brutalist notions.

As with Southside, the parts exist for the whole—each works with the others to make a seemingly illogical assembly appear both natural and pleasing to the eye.

Budget concerns make poured concrete common at publicly funded houses of learning. Not so with religious architecture, as wealthy benefactors usually have the coin to spring for expensive materials and the labor to arrange them in compelling patterns. Just three miles from Southside sits Eliel Saarinen’s First Christian Church, completed in 1942. Clad in brick and limestone, this building was the first in Columbus with a Modernist slant. It was also one of the first churches in America to embrace the approach.

Like carmakers, religious institutions can change quickly but often do not. In either space, steps outside the norm can define an era. More than ten years ago, Tesla set the EV stage with its five-door-coupe Model S, but the model has barely changed since, and the lines are now a bit stale. (The design also wasn’t particularly new, at least when viewed through the lens of the first Mercedes-Benz CLS. Or a few modern Hyundai Sonatas, for that matter.)

In that sense, the Ioniq 5 excels, no pun intended. It performs the relative miracle of looking like nothing else on the road while paying homage to both Hyundai history and the so-called “8-bit” era of design—the 1980s—where the company grew. Both car and church refine rudimentary forms into eye-catching statements.

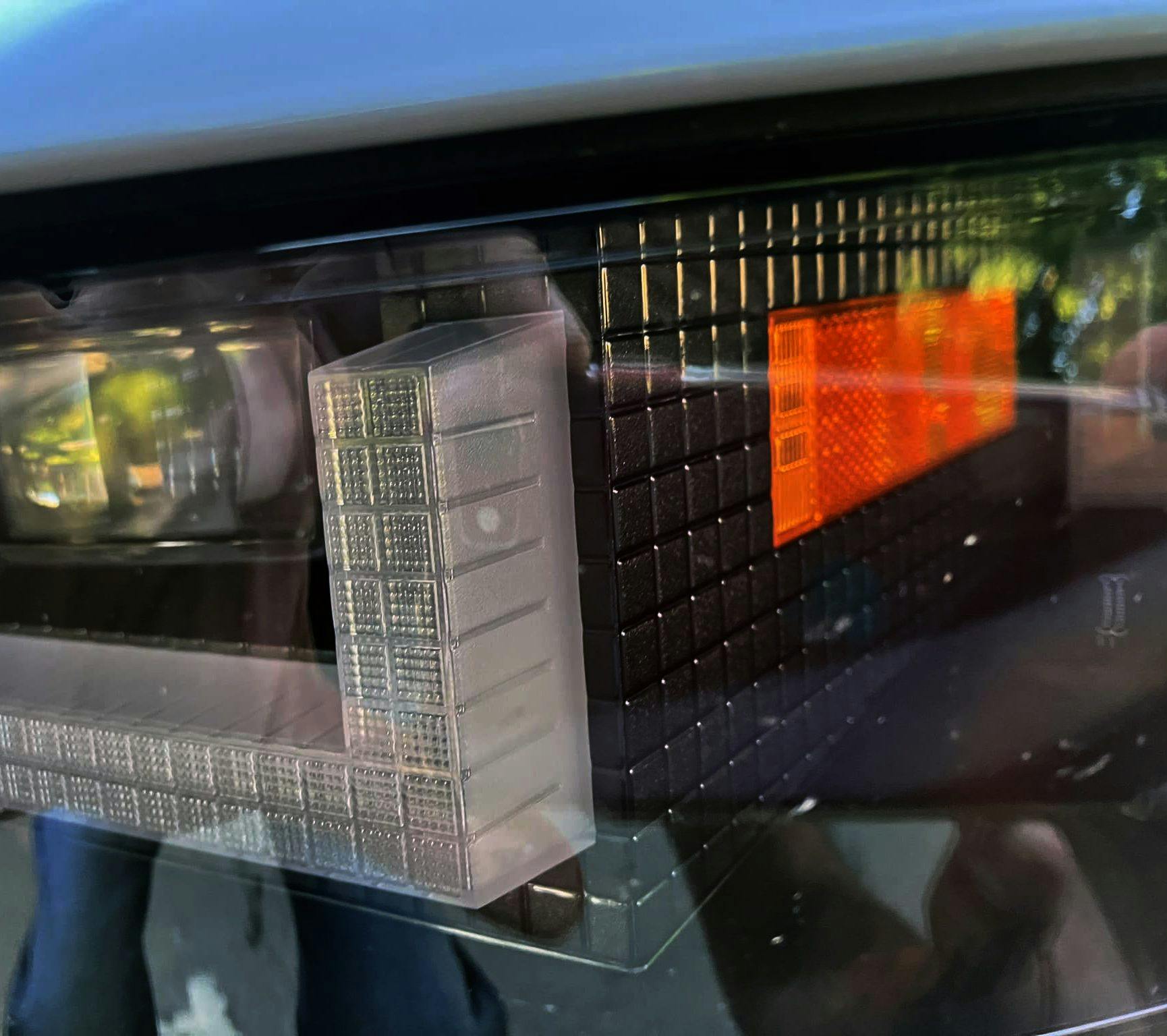

Like Southside Elementary, First Christian Church holds right angles and long lines, but diverse material choices and playful jabs at symmetry make its shape anything but brutal. Brick facades, rectangle-clad walls, and artful uses of symmetry and asymmetry abound. The main entrance is skewed off-center, slightly to the right, a cross centered over the uncentered doors. This is a small notion, moving two elements away from their expected location. But it also makes First Christian’s front far more engaging than a predictable façade.

Take a look inside the Ioniq 5’s headlights—there’s a similar approach in the Lego-like plastic texturing. The amber reflector, mounted on a panel that frames the high beam reflector, doesn’t necessarily need enlightened placement. It’s just a headlight assembly, right?

Hyundai pulled a Saarinen here, tension in asymmetry. There are five “squares” of black plastic between the reflector and the 90-degree bend in the front of its mounting panel. Fewer than two black squares exist on the other end of the panel: rudimentary shapes kept from being boring. Perhaps this is something you can build for yourself in Minecraft?

That shockingly popular video-game series points to a critical note with design of any type: The true impact of lighting and surface texture is only available in the real world. There’s no substitute for feeling the rough graining of poured concrete with your fingers or casting your eyes upon delicate shadows in real empty space. Analyzing the Ioniq 5’s headlights in words does not convey the experience of watching the car’s light show at a charging station. Nor can a keyboard convey the novelty of using a memorably styled electric car as both tourist shuttle and daily driver for a week.

With that in mind—and after a brief detour to line the Hyundai’s front bumper up against the imposing, and similarly shaped, Columbus City Hall—we headed five minutes across town, to the residence of J. Irwin Miller.

When it came to his own walls, Columbus’s most influential son did not skimp. Eero Saarinen drew the main structure, one of the few private homes he designed. The building, completed in 1957, is laid out axially, rooms spoking out from a central “hub” living area with conversation pit. The house is now a museum exhibit, available for public tour and owned by the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

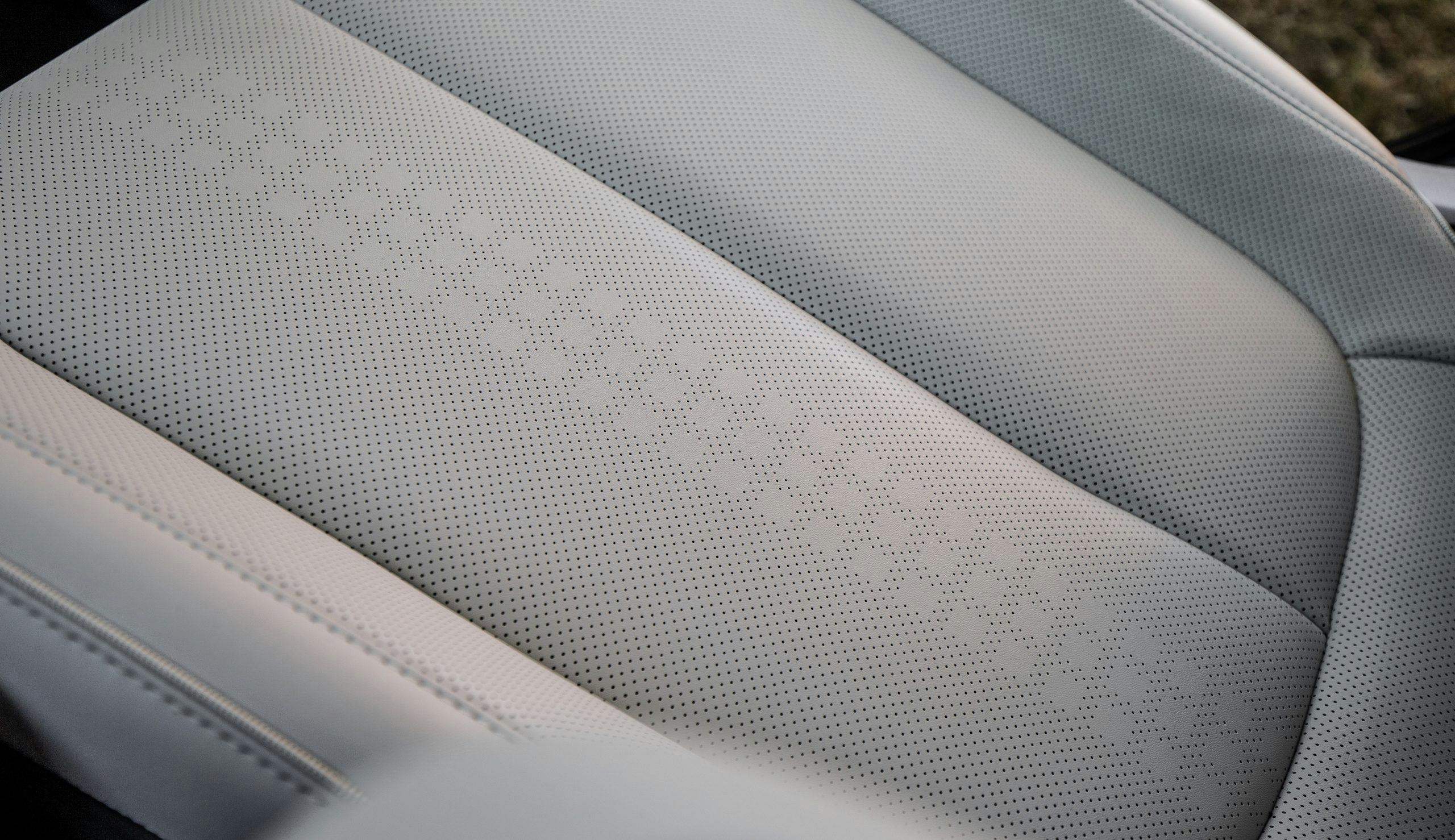

Miller’s residence is testament to how architecture must ultimately be made for use, and how Modernism can produce an inviting and inspired place to live. Poured-concrete floors becomes appealing for a home when you add bits of semi-precious stones and give the mix an Italian name like terrazzo. The house uses that material all over, even in the garage, where it is dyed black and sporting integral parking stops that rise from the foundation. From the outside, the structure is a low-slung rectangle. Inside, free-standing steel columns, wood trim, marble panels, floor-to-ceiling windows, and even the modest perfection of Formica paneling create something masterful.

As always, natural light is key. Those steel columns, 16 in all, support a grid of ceiling tiles and translucent skylights running the length of the house. They help to promote the painfully modest ornamentation, like how the chimney flue makes a seamless and fluid transition into the ceiling. They also create natural highlights in the most delightful and unexpected locations.

Man has modified light for centuries, going back to how early churches used stained glass to twist Mother Nature’s greatest gift into art. But it wasn’t until Modernism that light become a dominant element of interior design. Used properly, it can accentuate elements within a space without drawing attention to that manipulation.

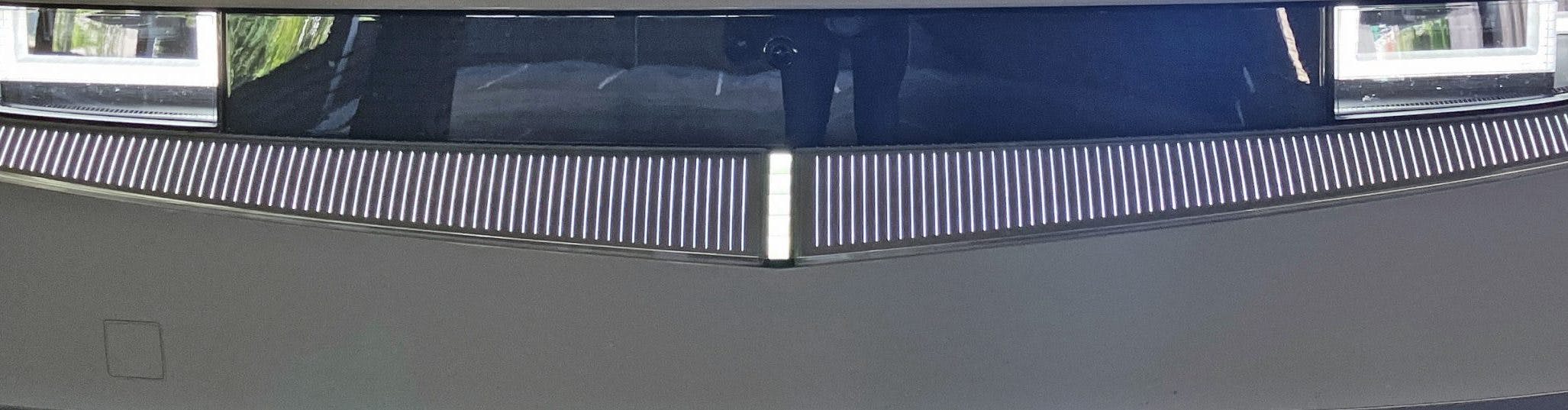

Walking back outside, I noticed a few more of the Hyundai’s details: accent lighting buried within the door-panel armrests, lighting around the speaker grilles, lighting integrated into charging meters via individual and square-shaped panels at the charging port and front bumper. Elegant hashmarks under the headlight assemblies form a bold signature, their pattern like Saarinen’s skylights.

Car and city complement each other here like peanut butter and jelly. In each case, parallels are everywhere, and there is simply too much to cover.

Columbus thrives to this day, even as its iconic architecture has required changes, additions, or complete destruction. The updates made to I.M. Pei’s public library are sympathetic and respectful to the original. When Ralph Johnson’s Central Middle School was demolished and rebuilt in 2007, the end product carried modernist undertones and recycled a whopping 83 percent of the original building. Perhaps this city can teach the likes of Troy Trepanier and Dave Kindig a thing or two about restomods?

The original Hyundai Excel was a poor fit for the American market, and the Hyundai Pony rusted far too quickly, but you can’t discredit their approach: Modernist Italian styling at a bargain-basement price. The Ioniq 5 has too much real estate and is too costly to recall the minimalist Excel, but the Pony’s influence is strong—hard lines meshing with soft contours for surprising elegance, the old as springboard for the new.

At the core, Modernism embraces change. Picasso turned the nude female form into a work of geometric abstraction. Le Corbusier’s mantra held that a house is a machine for living in, and the idea reinvented urban planning. More than half a century separates vehicle and architecture here, but the common thread is a clear aim to change lives for the better. Done right, the result looks almost too easy, though it’s clearly anything but.

Want more stories from our Great Reads project? Click here.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark us.

I don’t know much about architecture, but to hear or read an expert explain it is always fascinating. Great article.

I am glad that you enjoyed it. Thank you so much for reading!

This is a very interesting and well-informed article, a really enjoyable read. I’m unlikely to buy an Ioniq, or any EV for that matter, for some time, (if ever), but I found the styling attractive immediately the first time I saw one.

En passant, while the Hyundai Pony wasn’t available in America, it was available in Canada where it sold very well for as long as it was available here. The caveat to keeping one here was not to have it rustproofed per se, but oil-sprayed, although even at that they still couldn’t stand the road salt of Canadian Winters. At the time, they were clean designs and looked like nothing elses on the road, just as the Ioniq does now.

Thank you for reading, I am happy that you enjoyed my article. I have relatives in both Toronto and Edmonton, so the Hyundai Pony was a big part of my time in Canada. They were everywhere, they were rusty but there seemed to be a level of respect for the fact that they existed to fill a need. There wasn’t much else you could compliment about a car that rusts too quickly in Canada, but I am glad to see their design inspired you to write that (looked like nothing else on the road), as I felt the same way about them too.

A brilliant article! It fosters closer inspection and greater appreciation of both the architecture and the vehicle.

Thank you!

Nope. Not for me. And I’m not even talking about the EV part. I just couldn’t bear to buy a brand new vehicle that comes “pre-creased” or “pre-dented” in the door area.

I’ve been saying for at least two months that the Ioniq 5 will appear one of these days in Moma–and I haven’t said that about any other recent car. So I particularly enjoyed reading about the Ioniq 5 in this article, comparing it to architecture.

I also have to admit that I hadn’t analyzed my attraction to the Ioniq 5, so it was nice to have Sajeev do it for me, with allusions not only to the car, but to architecture.

I will be emailing this article to a friend of mine–not really a car guy–who bought the Ioniq 5 for the electric power. His wife, owner of a Jetta diesel that I’ve mentioned in these pages, is the car person in the family. (To find the mention quickly, go to the last subhead in this article, and start reading.)

https://www.hagerty.com/media/opinion/the-damage-done-by-renewable-fuel-to-classics-and-the-planet/

Thanks for reading and your kind words, David. You are right, this car and MoMA really do go hand-in-hand…almost as much as it does with Columbus.

Since you mentioned Tesla, I have to add to my previous comment that I think everything that’s come after the Model S has been quite ugly–as if they put no effort into aesthetics whatsoever, both exterior and interior.

Several months ago, I began telling people that the Ioniq 5 would be shown in MoMA one day. It is a superb piece of automotive styling in an era of poor styling. (The ’10s was the worst decade ever for automotive styling, but the ’20s are showing marked improvement.)

Anyway, thanks, Sajeev, for providing such a thorough explanation of why the Ioniq 5 is such a great piece of styling.

Always been obsessed with brutalism so I guess it makes sense I bought an ioniq 5 as opposed to yet another Audi or BMW

Hats off to you, as you are truly living the dream.

Sajeev, re-read this great article after you mentioned it in your ’10 Automotive Adventures’ article – I didn’t mention it then, but your article made me look up the Miller House and dig into more pictures of this excellent example of Mid-Century architecture. Re-reading this was refreshing and enjoyable – again! Thanks for great and thoughtful writing.

Oh wow, I am glad you enjoyed it again and I am especially glad you commented about it! You absolutely made my day!