Media | Articles

This is McLaren racing chief Zak Brown’s U.S. office

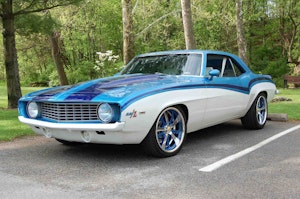

Proudly parked among all the gleaming zillion-dollar custom coaches lined up in orderly rows in the paddock at the recent Acura Grand Prix of Long Beach was an ancient Ford Condor II motorhome that looked like it had just driven off the set of Vanishing Point. The mustand-and-white paint job and old-school “McLaren Engines” stickers hint at the rig’s reason for being at a race, and a roll-out canopy serving as shade to lunching crew members of Arrow McLaren SP, the modern-day IndyCar effort of McLaren, proves that this 50-year-old motorhome still works for a living.

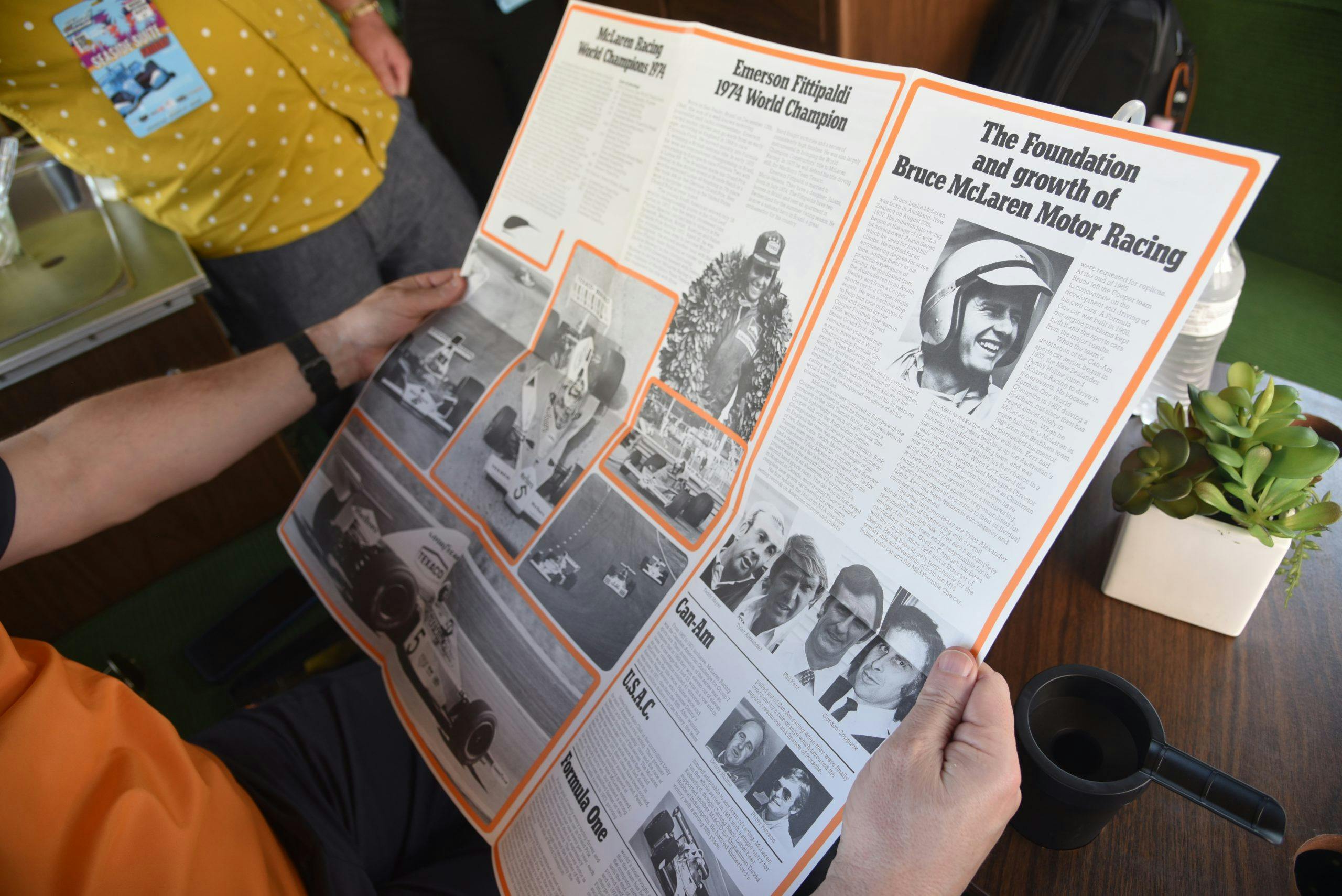

The rig belongs to Zak Brown, the chief of McLaren Racing. He was in Long Beach to not only oversee his company’s recent investment in an IndyCar team, but also to race his own 1989 Jaguar XJR-10 IMSA GTP car in the event’s supporting historic race. Explains Brown of the 28-foot-long RV, which is the real deal, having formerly served as a McLaren Engines team support and trackside hospitality vehicle at Can-Am, F1, and USAC races back in the 1970s: “A buddy of mine found it on Bring-A-Trailer, so this was a must-buy.” Brown had had his friend bid for it “because I figured a McLaren CEO buying a McLaren motorhome is not a good way to start negotiations.” It sold on BaT last June for $32,500.

If you’ve been watching the Netflix series Formula 1: Drive to Survive, you’re familiar with Zak Brown, the seemingly unlikely American in charge of McLaren Racing. In a series dominated by cutthroat Europeans with ice water in their veins, Brown comes across as the sport’s real-life Ted Lasso, a slightly folksy leader of an underdog team who gets his pouty young stars to perform through repeated enthusiastic attaboys and high-fives. The truth may be slightly different; the native of North Hollywood, California was a racer himself, then made a considerable fortune in sports marketing before joining McLaren in 2016 and signing on as chief executive officer of McLaren Racing in 2018. You don’t get to the top by being a nice guy—at least, not all the time.

Now Brown, based at the company’s headquarters in Woking, England, swims with the sharks of F1, where the top teams employ 1000 people and annual budgets are around $350 million. Last year he orchestrated the purchase of the Arrow Schmidt Petersen Motorsports IndyCar team, which fields a pair of spec Dallara IR18 chassis for drivers Pato O’Ward and Felix Rosenqvist. Compared to F1, in which the teams build and develop new cars every year, McLaren’s 150-person IndyCar team is one-tenth the size and cost to run, says Brown, thanks largely to the limited travel and the spec Dallara chassis, which the team buys for $1.5 million each (plus a few $250,000 2.2-liter twin-turbo Chevy V-6es) and can do little to change.

“We have a long history here,” says Brown of McLaren’s interest in IndyCar. “We’ve won Indy three times, and the North American marketplace is important to the McLaren brand, our fans, and our corporate partners.” Yeah, but was it so important to have an IndyCar effort with the 2023 F1 schedule now containing three U.S. races, the most ever? “Even though Formula One is growing here, we wanted to have a bigger North American platform than all the other F1 teams,” answered Brown. “Being in Indycar allowed us to double down on the market.” McLaren’s drivers finished 5th and 11th in Long Beach, which was round three of the 17-race IndyCar schedule for 2022.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

In his precious few minutes of spare time, Brown also collects vintage racing and road cars, and now boasts a collection of 33 racers and 13 road machines. Highlights include a ’65 289 Cobra, a Ferrari 288GTO and F50, one of the World Championship-winning John Player Special Lotus 79 F1 cars driven by Mario Andretti, Alan Jones’s 1980 championship-winning Williams FW07B, several significant Indy and rally cars, Ayrton Senna’s 1991 McLaren MP4-6 as well as a DAP go-kart that a young Senna raced in 1981.

Thus, the vintage Condor II, based on a Ford M-504 motorhome chassis coaxed forward by a big-block 390 FE V-8 and Cruise-O-Matic three-speed auto, wasn’t much of a stretch for Brown. “This was a personal purchase,” he says of the motorhome, which now lives at Arrow McLaren’s race shop in Indianapolis and goes by flatbed to races. “I haven’t driven it yet, but I have started it up. It goes to all the (U.S.) races I go to, it becomes my office.”

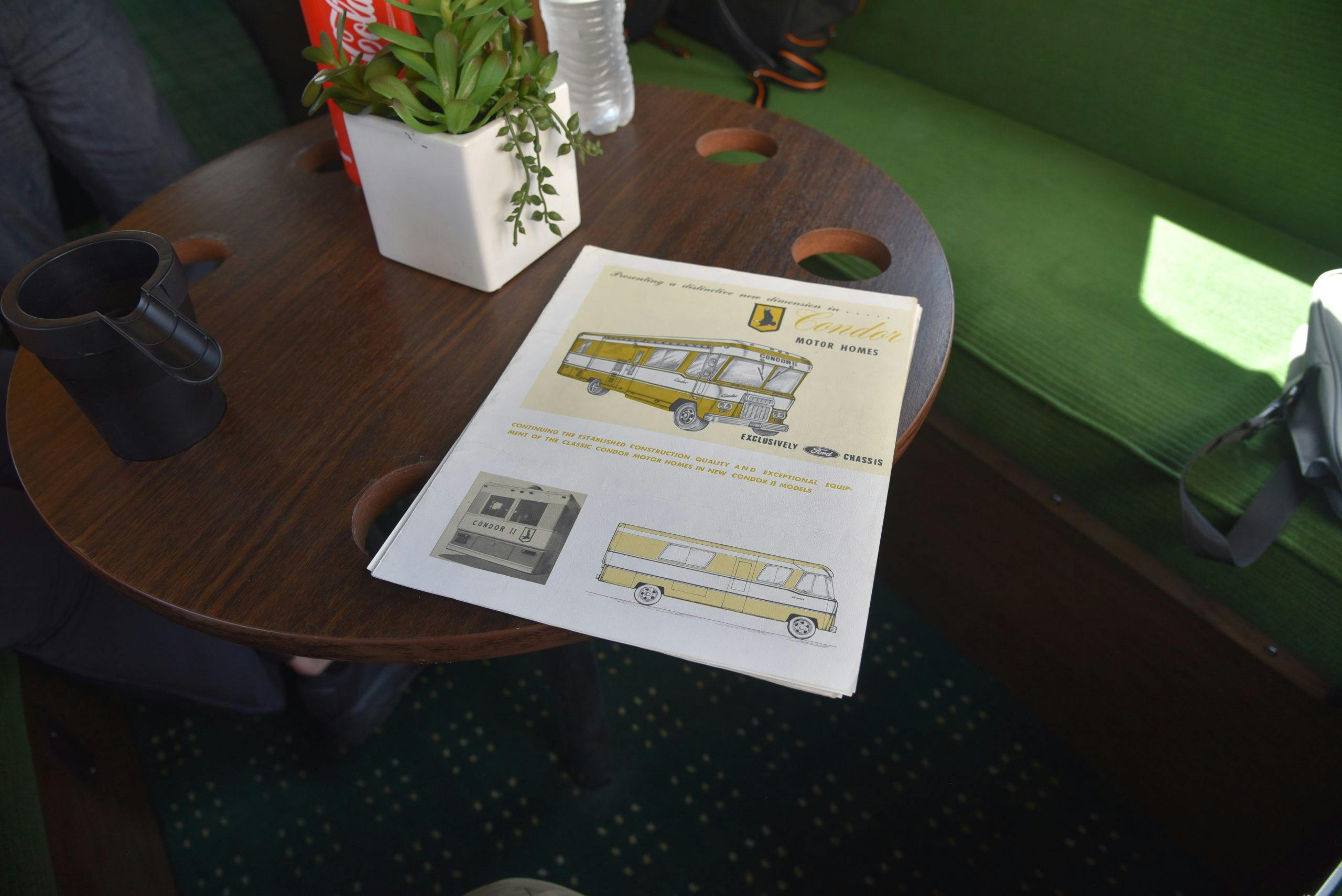

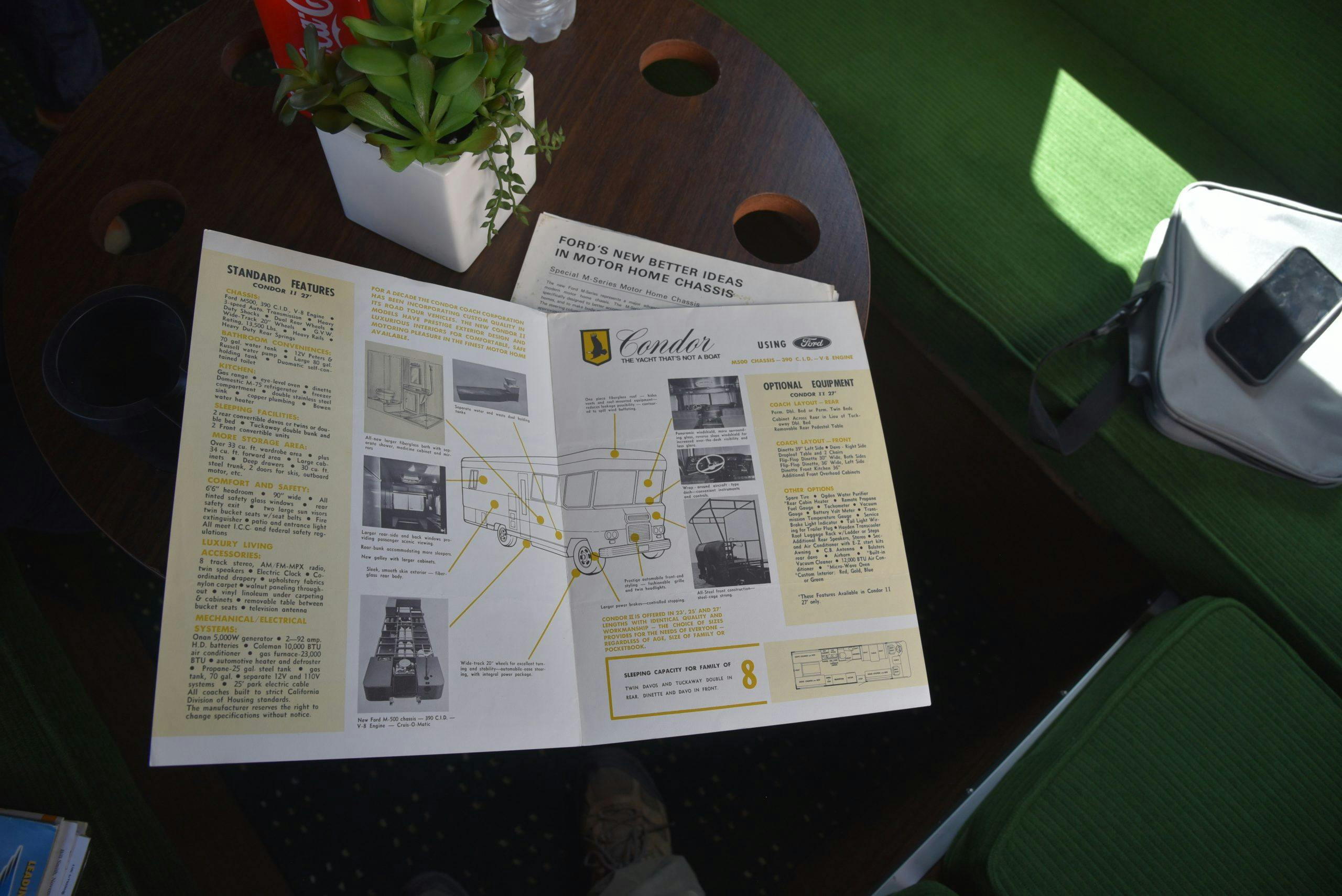

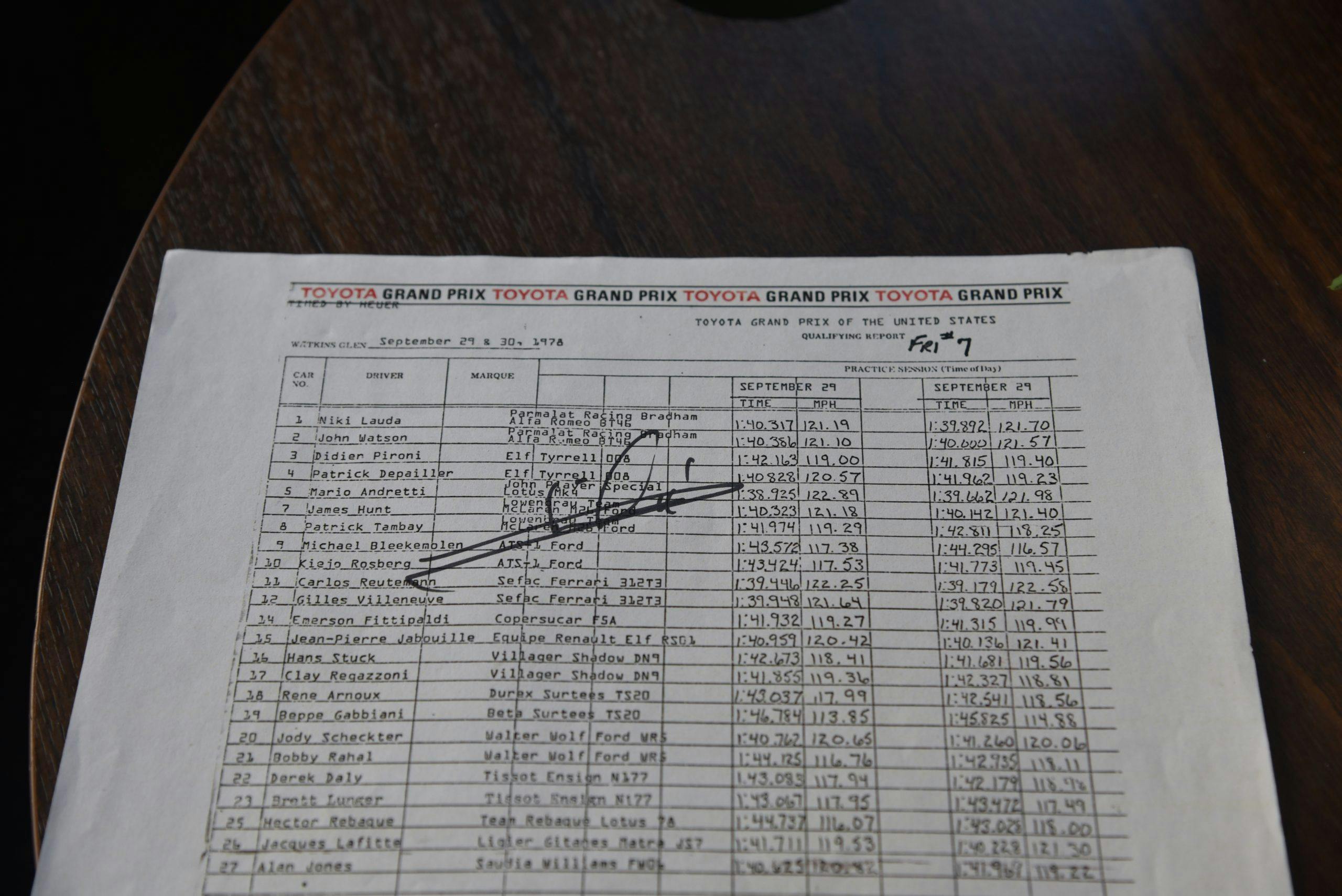

Brown says the RV needed some mechanical work underneath, but otherwise is all original, down to the acres of laminate walnut paneling, forest-green carpet and cushions, trumpet-shaped lamps, four-hob stove, and large embedded wall clock above the driver. Among the documentation that came with the purchase were yellowed McLaren promotional brochures and Friday qualifying sheets from the 1978 Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach. McLaren drivers James Hunt and Patrick Tambay were running seventh and eighth, respectively, that day.

Los Angeles-based Condor Coach Corporation aimed high with the Condor II, marketing it as “the yacht that is not a boat.” Standard features included a 70-gallon fresh-water tank and 80-gallon holding tank, a generous six-feet, six inches of interior headroom, a full kitchen with gas stove and oven, a bathroom with shower, loungers in the rear that converted into a master bedroom, tuck-away double bunk beds up front for the kids, color-coordinated drapery, and an 8-track player in the “wraparound aircraft-type dash.” The reverse-slope windshield so common in RVs of the period promised better forward visibility if no better fuel economy. We’re guessing well under 10 mpg, which is why it’s probably cheaper to flatbed it to races than it would be to drive it.

When we met Brown, he was about to jump into the Castrol-sponsored TWR Jaguar GTP car, which ran from 1989 to 1991 and won four races in the IMSA Camel GT series. American Price Cobb, Dutchman Jan Lammers, and Danish driver John Nielsen all took star turns in the turbocharged, 800-hp V-6-powered sports-prototype back in the day. Says Brown: “It’s geared for 195 mph on the front straight. It’s as fast as the IndyCars.”

At Long Beach, which Brown considers his “home race” since racing here in Indy Lights a quarter-century ago, his Jaguar would be up against other hero prototypes of the era, including a Porsche 935 and 962, a Mazda 787 and RX-792P, and Toyota AAR Eagle Mk III from 1991. Brown said his goal for the race over the bumpy street circuit where concrete walls stand ready to punish even minor missteps, was “survival.”