Media | Articles

This ’48 oddball sent its inventor to court—and it’s not a Tucker

In 1948, the same year that Preston Tucker rolled out the first of his cutting-edge Tucker 48s, another “car of tomorrow” was born in southern California. The two stories are oddly similar in that only a fraction of the planned production run became reality, and the cars’ industrious creators both ended up in court. Except no one ever made a movie about the Davis D-2 Divan, and only Preston Tucker was exonerated.

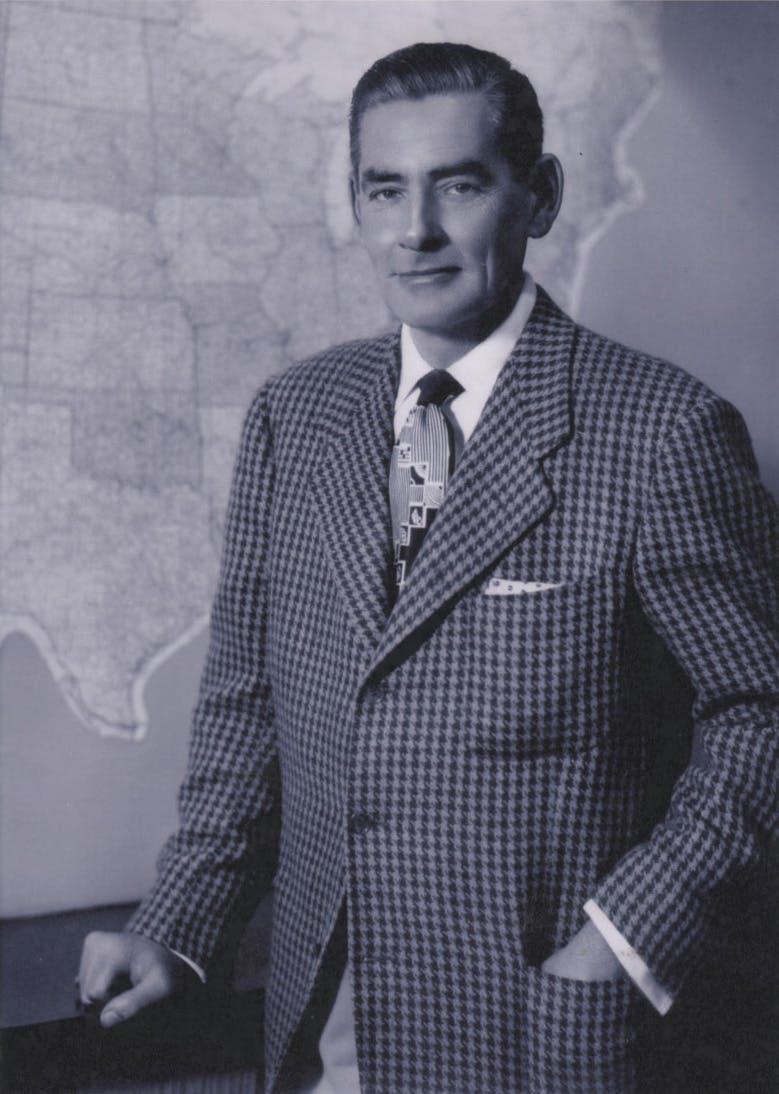

The Davis story actually began with another car, a one-off three-wheeler that millionaire and part-time Indianapolis 500 racer Joel Thorne commissioned in 1941. Called the Californian, the car was designed by Frank Kurtis, founder of the Kurtis-Kraft roadsters that raced at Indy. It caught the attention of Glenn/Glen “Gary” Davis, a former car salesman who had befriended Thorne, and he was immediately struck with an idea. Whether or not that idea was completely wholesome has been debated for decades.

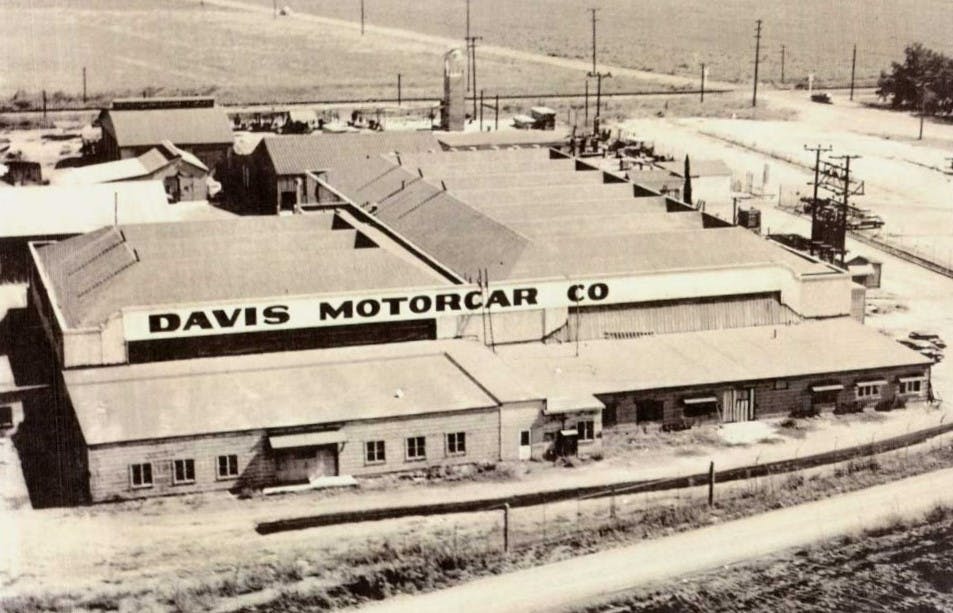

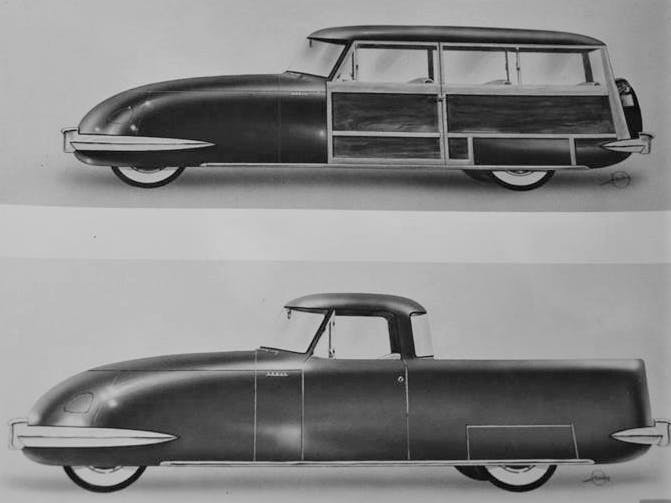

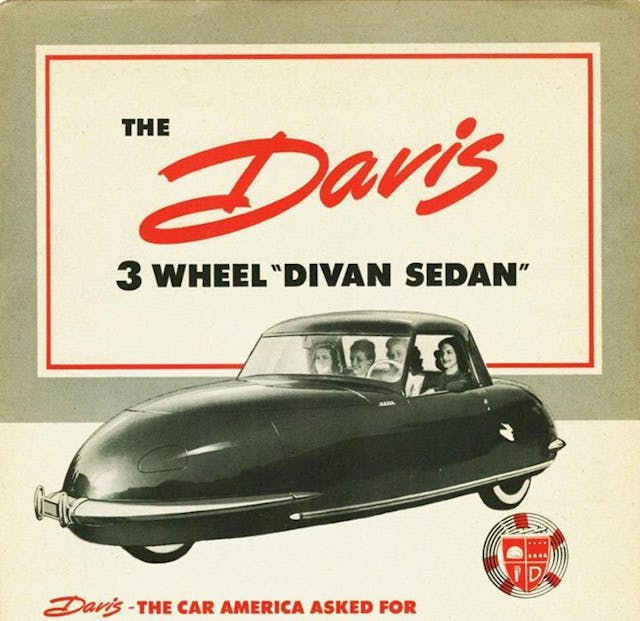

Davis managed to acquire the Californian from Thorne in 1945, and he immediately hired a team of young engineers to reverse-engineer it. They eventually built a scale model of the “new” car, photographed it for a July 1947 story in the Hollywood News Citizen, and claimed they could build 50 of them a day. Davis soon created the Davis Motorcar Company and began to tour the country with the Californian, since there was no actual Davis car to show yet. Cashing in on dealership agreements—and the U.S.A.’s post-World War II thirst for new cars—he claimed that the sleek, aluminum-bodied three-wheeler was “The Car America Asked For.” Davis’ marketing savvy proved effective as he raised more than $1.2 million (equivalent to more than $15 million today) to build the Divan.

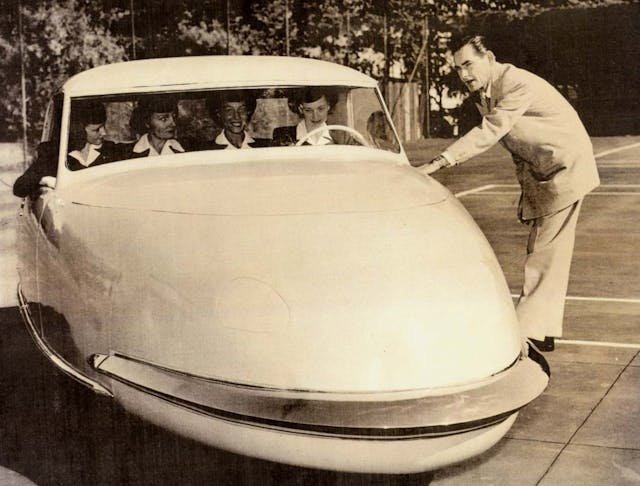

A prototype nicknamed “Baby” was officially introduced in November 1947 at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. The car was then repainted and displayed in a Philadelphia department store during the holidays before being repainted once again for an appearance in the 1948 Rose Bowl Parade.

Building the Divans in an airplane hangar in Van Nuys, Davis promised his employees that if they worked for free until the cars began to sell, he would pay them twice their agreed-upon salary when the money started rolling in. What could go wrong? Whether or not they fully trusted Davis, they believed in the Divan, and production began in early 1948.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

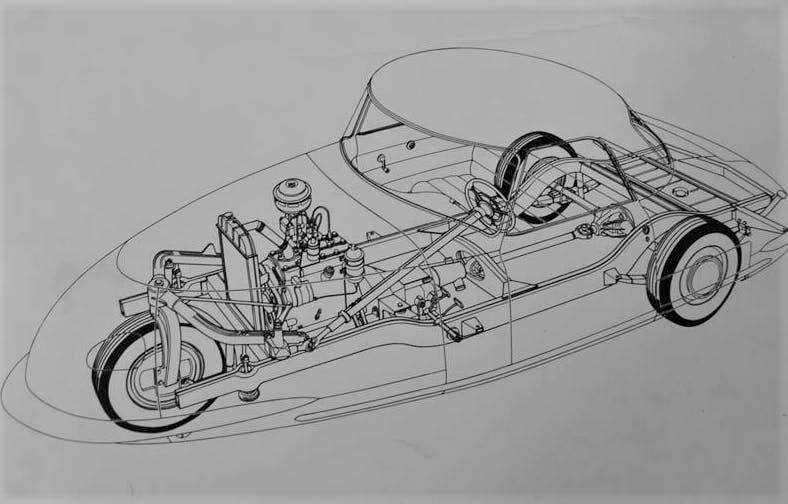

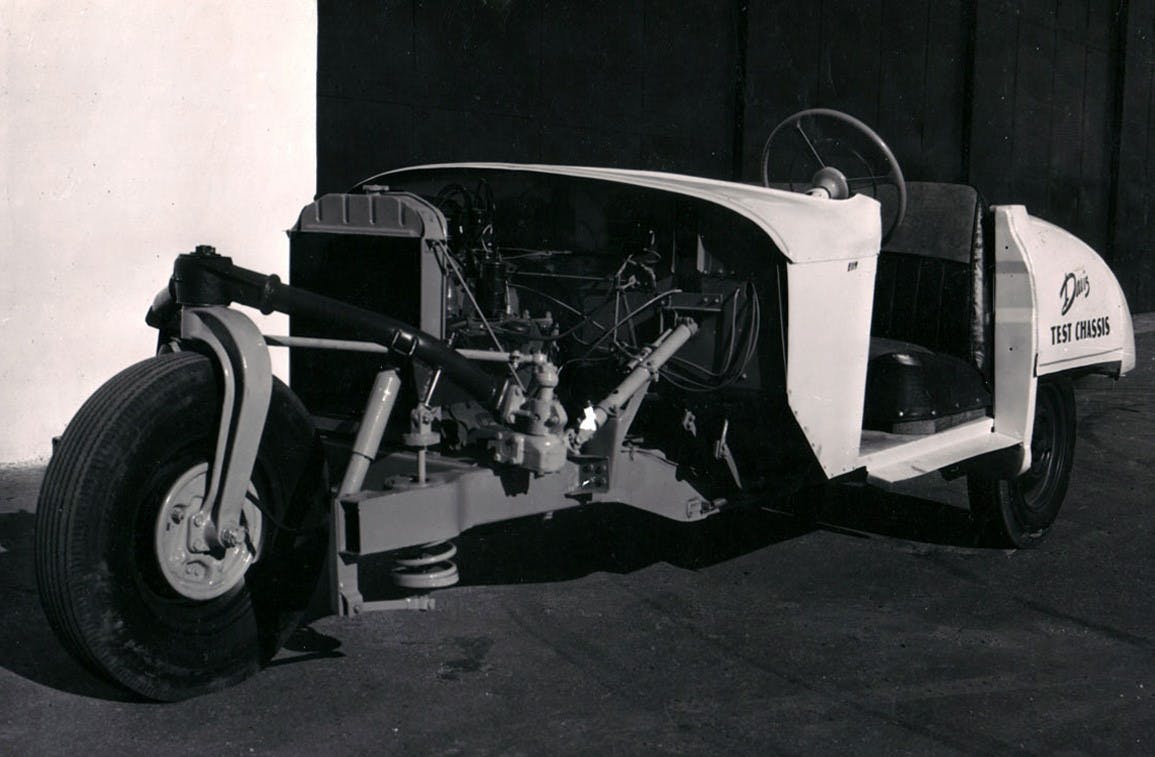

The Divan certainly seemed to be a worthy car choice for those looking for a solid (albeit unusual-looking) vehicle to match their budget. Oval-shaped with aerodynamic body panels, the two-door sedan featured one 15-inch wheel in front and two in back. Power for the “production” cars was provided by a 63-horsepower, 162-cubic-inch Continental four-cylinder engine mated to a Borg-Warner three-speed manual transmission. Davis’ marketing materials called it “a three-wheel engineering triumph!”

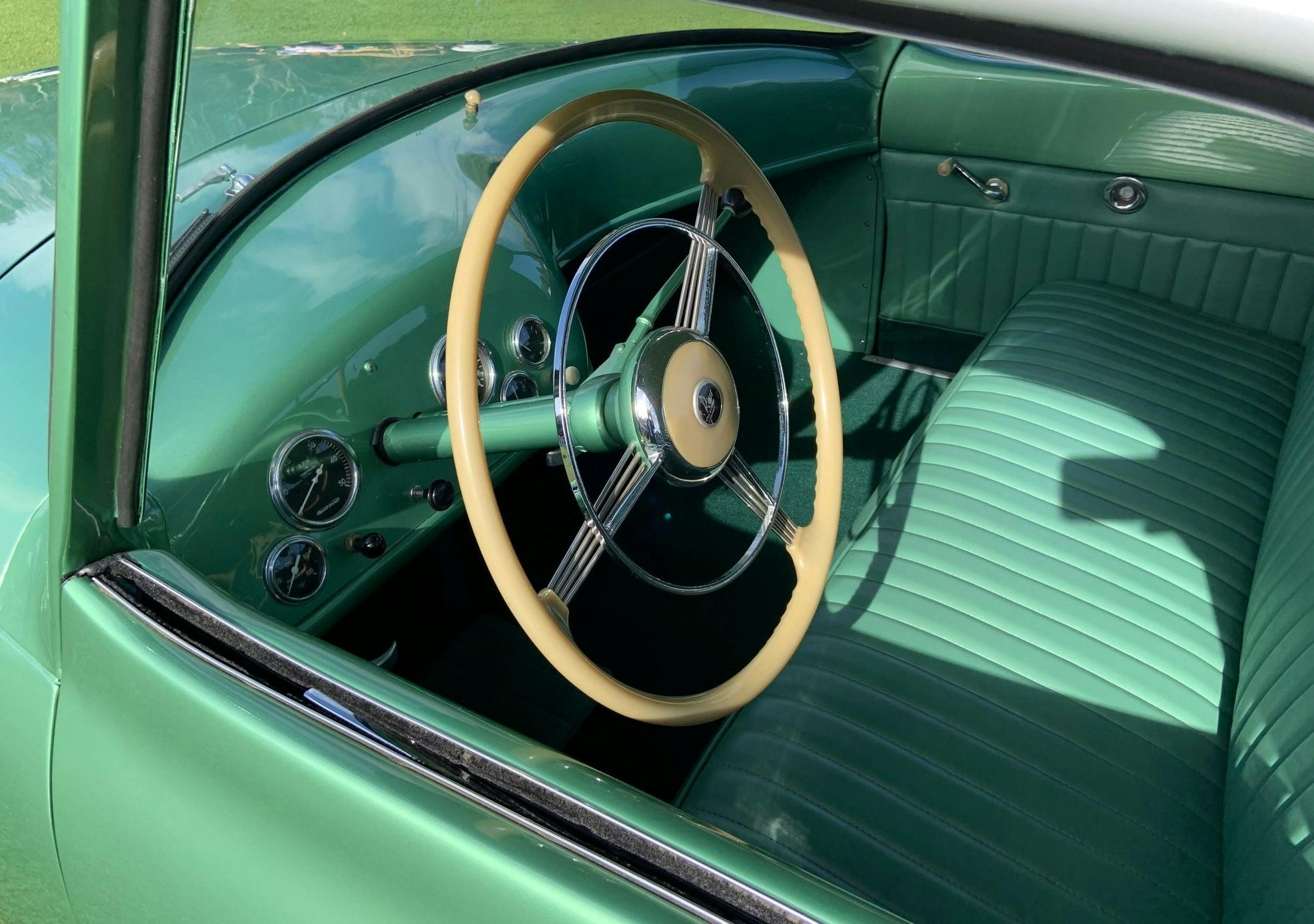

The Divan, which had a 108-inch wheelbase and a curb weight of 1385 pounds, offered features like a removable hardtop, headlights with covers that open inward, push-button door releases, wrap-around bumpers, a 64-inch-wide bench seat with “hiproom for four adults,” and a curved, shatter-proof, plate glass windshield that “yields 30 percent greater visibility.” Davis also claimed that the “distinctive design of the steering and instrumental panel provides the efficiency, dignity, and charm so long sought after by every motorist.” Although that sounds fantastic, in reality it translates to unremarkable and minimalist.

While the shape alone makes the Divan a head turner, one of the car’s more cutting-edge features is invisible to the naked eye. Each of the three wheels has a built-in jack so that with a flip of a switch, military surplus hydraulic cylinders lift the car for easy access to change a tire or make a repair.

With a list price of $995 ($11,700 today), Divan advertising shouted, “No car—in any price class—can boast better styling and engineering.” But it wasn’t meant to be, and some suggest that it didn’t work because it all a money grab.

Only 13 Divan sedans and a couple of military variants were built, and by May 1948 the company was in trouble. Dealerships were growing impatient, unpaid employees sued, and the Los Angeles district attorney opened an investigation. In the end, the factory was shuttered, the assets were liquidated, and—though Preston Tucker was cleared of similar charges—Davis was found guilty of 20 counts of fraud. He served two years.

“Davis was sort of a flim-flam artist,” says Wayne Carini, whose Divan was awarded Best in Class at The Amelia, which brought together five Divan sedans and a military vehicle. “But he built a cool oddball, and I love oddball cars.”

If you’re into Davis Divans, Carini’s is the one to have. It belonged to none other than Gary Davis himself.

“A friend of mine called from California and said he’d found a weird car that I might be interested in, and it was once owned by [actor] Nicholas Cage,” Carini says. “I took one look at it and bought it. I took it to cars and caffeine in Irvine the very next day, and I met a guy who had been Davis’ personal assistant. He was in his 80s, and he said, ‘That was Gary’s car.’ I asked how he could possibly know that, and he said, ‘I personally repaired a crack in the suspension one night. I’ll show you.’ And there it was.”

Today, a 1948 Davis Divan in #2 (Excellent) condition is valued at $80,300, while a ’48 Tucker in #2 condition is worth $1.65M. Much like the similar but divergent stories of their creators, one became an icon, the other is just a footnote in automotive history.