Media | Articles

The Schuppan 962 CR is the ultimate non-Porsche Porsche supercar

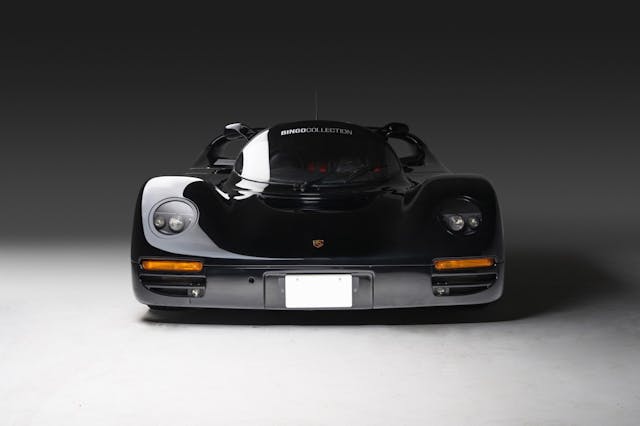

This year’s Rennsport Reunion was the largest Porsche gathering in history, but one car on display at Laguna Seca has never been officially recognized as a Porsche at all—the Schuppan 962 CR, a street-legal supercar based on Porsche’s dominant 962 Le Mans racer. It now stands as one of the rarest and most beautiful supercars of all time.

Sadly, the 962 CR was also a car that financially ruined the man who put his name to it—former Porsche works driver Vern Schuppan. With Schuppan also in attendance at the California event, it was the perfect opportunity to get the story first-hand.

Born in 1943, Schuppan was raised in Australia, where he got his first taste for motorsport in junior karting, and by the early 1970s had moved to the U.K. and broken into the top single-seater classes—Formula 1 and European F5000, and, in the States, IndyCar racing.

He was also fast becoming recognized as a talented endurance racing driver. In fact, Schuppan’s endurance career would long outlive his single-seater days and provide foundations for the 962 CR project, not least when Porsche came knocking with a works drive for 1981.

Aged 40 in 1983, Schuppan achieved his greatest success, winning the 24 Hours of Le Mans in a Porsche 956 with Hurley Haywood and Al Holbert. That same year he also won the inaugural All Japan Endurance Championship with Porsche customer team Trust Racing.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Flush with success, Schuppan set up his own team in 1987: Team Schuppan. Based out of High Wycombe to the northwest of London, the outfit campaigned Porsche 962s (successor to and close relative of the 956) in World Sports Prototypes, All Japan Sports Prototypes, and IMSA through to 1992.

“That led to Rothmans asking if I could run a team in Japan for them [from 1987], so I was racing for the Japanese against my own car,” recalls Schuppan. “I was astonished they agreed to that. Then Omron came to me about running a car, then Takefuji.”

By this time, teams including Kremer Racing, Team Joest, and designer John Thompson were developing bespoke components and even entire chassis for the 962, in a bid to improve on the original aluminum monocoque. It was a logical step for Team Schuppan to explore opportunities of its own.

“I went to an aerospace company in the U.K. [Advanced Composite Technology Limited, or ACT] about building a carbon 962 chassis,” recalls Schuppan. “Mr Singer [Norbert, Porsche engineer and Le Mans mastermind] liked the idea and provided the blueprints, so I started running a carbon chassis on the Omron car and the Takefuji car. We also started doing some of our own components manufacture.”

The leap to a road-legal 962 came not from Team Schuppan, but from a racing enthusiast who worked at Kosho, one of the Nomura Group [Japanese investment bank and brokerage firm] of companies, which Schuppan describes as invested in building hotels and golf courses. One employee would come to races and chat about a road-legal Le Mans car during the 1989 season, and soon things were happening through Vern Schuppan Ltd, another eponymous venture set up alongside Team Schuppan.

“We turned one of our Le Mans cars into a mule for that project and got it through all the type-approval process—emissions standards, things like that—but it didn’t have to be changed massively, so that was the start of it,” Schuppan recalls.

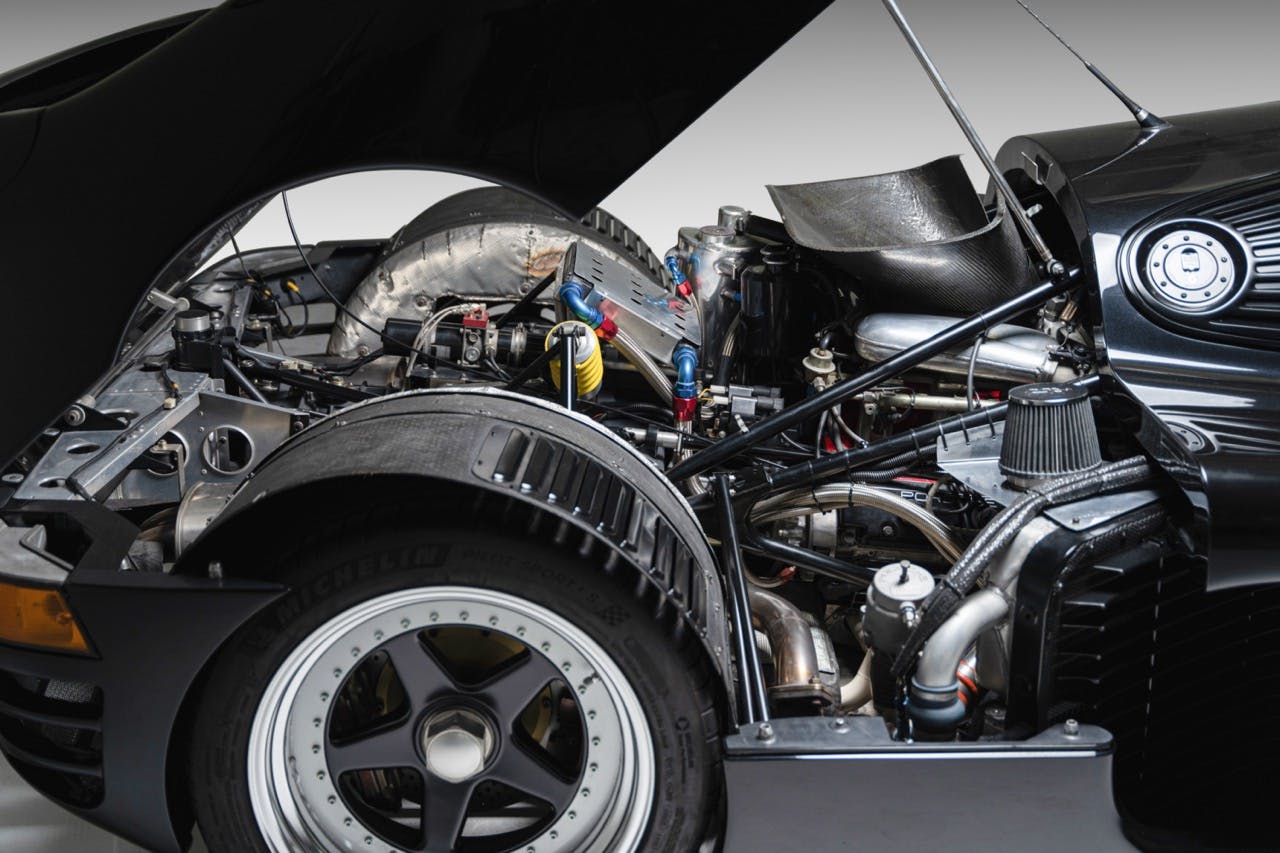

Known as the 962 LM, all these cars used the ACT carbon-fiber chassis and the 962’s 2.65-liter turbocharged flat-six engine, with four valves per cylinder and quad cams. They were produced at the one-time Tiga Cars factory, founded by former F1 drivers Tim Schenken and Howden Ganley—the latter involved in the Schuppan project.

“The first LM was built in early 1991, but by then the financial crisis was coming into play and building hotels and golf courses didn’t look so clever, so Kosho only took three cars. Then I was approached by one of our sponsors in Japan saying he could put a deal together with Art Sports Corporation [AS]. They wanted 25 cars, and at first it was supposed to be a Le Mans–bodied car. Then they changed their mind about that and wanted more of a GT look.”

With tooling already created for the LM, it meant “almost starting again” to create what would become the 962 CR, with a new chassis built by Reynard—it would be evolved from the ACT carbon-fiber chassis but some two inches wider to free up extra cabin space. The CR would also be powered by the 962’s flat-six, this time to IMSA specification with 3.4 liters, with two-valve single-cam heads and full air cooling. It made 600 bhp.

The plan was to build 25 to 50 examples, each priced at 195 million Yen, equivalent to around £830,000 in 1994. That made the CR three times more expensive than the XJR-15, a similar project created by Tom Walkinshaw Racing from the bones of Jaguar’s Le Mans racer. “Tom was interested in our car and I drove his car, actually,” Schuppan says with a laugh. “I didn’t think it was very good.”

Vern Schuppan Ltd. became a big operation, with as many as 60 people working on the 962 CR when the wider network of suppliers was factored in. VSL even bought out a composites business owned by former March F1 employee Bill Stone, allowing it to bring production of the CR’s carbon fiber bodywork in-house.

The dark blue car on display at Rennsport Reunion was the 962 CR prototype, an example unique in that it was built on a carbon-fiber chassis identical to the Omron 962 Le Mans race car—only later examples use the wider Reynard monocoque, including the car photographed, which is available at BingoSports in Japan.

It’s a beautiful car. Compact and low-slung, the design flows with organic sleekness from nose to tail, but it is also immediately recognizable as a Porsche. That’s in part because the teardrop canopy clearly references the 962 Group C race car as engineering hard points no doubt dictate, but perhaps more impressive is how neatly integrated Porsche road-car cues are with the rest of the bodywork.

Key to the family resemblance at the front are ellipsoid headlights and a plunging neckline of a bonnet set between raised front wings, almost like a 911 sticking its head out of a car window. At the back, a hoop rear wing visually flows into taillights linked by a full-width reflector, much like on Porsche’s own supercar of the era, the 959.

The 962 CR could easily be mistaken as an internal Porsche project. In fact, Schuppan explains that the project actually began with Ray Borrett, head of prototype production at Holden, GM’s Australian subsidiary.

Schuppan subsequently commissioned three design studies before settling on a winning design from Mike Simcoe, then global head of design at GM. “Mike’s design was streets ahead of the others. He was working for Saturn at the time in the U.S., going back and forth to England and not just designing the car but working on the buck, changing radii, spending all weekend on it.”

Ralph Bellamy worked on the dynamics, an Australian-born ex-Lotus and ex-McLaren race car designer whom Schuppan credits with pioneering ground-effect in motorsport. All the while, pressure to complete the 962 CR was immense.

“I tested the LM on the MIRA [test track] banking and drove it on the road to Silverstone, but I never got to drive the CR for any length of time because the Japanese were constantly on our case. Ray said it would have been almost impossible to get that car done at GM in the timeframe the Japanese wanted,” Schuppan says. “A team of guys came over for the final test at MIRA, in 1991, including journalists from Car Graphic in Japan, then we immediately handed over the prototype and they flew it to Japan.”

Despite the pressure, it was a case of so far so good, but the project quickly unravelled when AS replaced the 962 CR badging with a Porsche crest and announced it had full worldwide rights to Porsche’s supercar. As soon as Stuttgart heard the news, it immediately pulled the plug on its supply of parts, including 20 engines that were due to follow the five already delivered. Shortly afterward, AS reneged on its side of the agreement, making VSL’s growing debt increasingly impossible to service.

Before the deal collapsed, Schuppan says, “we needed a larger factory and started to buy somewhere, on the agreement AS put up some of the money for it. Part of the deal was that each time AS took delivery of a car, some of the loan principle was paid off. When they decided to bail out they called in the loan and gave us 14 days to pay them back. We had no money coming in, we couldn’t.”

A £6 million cancellation clause seemed to offer VSL a get-out-of-jail-card, until AS’s lawyers fully interrogated the contract.

“They hired a notoriously nasty law firm in London who tried to have the court case increased from two weeks to two months, eventually settling on five weeks. They’d already run us out of money, and I had to find another £300k as security against costs. We were getting calls at 3 a.m. and reams of faxes on a Friday night. In the end, we lost our house and cars, including my Le Mans-winning 956.”

Schuppan says he eventually persuaded AS to agree to take ten cars, but when even that fell through, he flew to Japan and secured a deal for three. “That would have generated almost enough money to save us at £900K, but I don’t think they believed we could get three cars done. We did and sent two to Heathrow, but Arts’ lawyers called for an emergency hearing in the court the next day to say their contract allowed extra time to road test the cars.”

When the judge ordered a road test could go ahead and put the onus on Schuppan to have the cars unloaded, the plane was already preparing for take-off. “As soon as the plane took off, Arts’ lawyers called Barclays saying I’d disobeyed a court order and was in contempt of court, and Barclays refused to pay the letters of credit,” Schuppan says.

Eventually, one car came back to the UK and one in remained in Japan. The prototype was in a dismantled state and in total only three examples of the 962 CR were built – one prototype and two production cars; there was also a hybrid of an air- and water-cooled Le Mans 956 and 962 CR for AS to race at Le Mans.

Looking at the CR beside us at Rennsport, Schuppan glows with pride, but the color soon drains from his face when I ask if he could imagine a continuation series, perhaps finishing the originally planned 25-car minimum run on a built-to-order basis. “Never,” he laughs. “I have no interest in getting back into that. It came close to destroying our lives.”

The 962 CR, then, seems destined to remain one of the most desirable supercars of all time. Not only does it tick the usual boxes of race pedigree, cutting-edge technology, and a design to die for, but it also boasts a backstory like no other plus an exclusivity its modern-day descendants can only dream of.

Schuppan does reveal Porsche has sold models of the CR at its museum, so it’s a pity the firm still doesn’t officially recognize its illegitimate offspring. If it had a change of heart, the 30th anniversary of the 962 CR’s demise wouldn’t be a bad place to start.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Well, now that I have seen & read about the absolutely most beautiful car ever, this old man can now die with a smile on his face! No, wait. I first must see it in person. Then I can peacefully die. No, wait. I must first sit in it then die. No, wait. I must turn the key. No, wait. Does it handle anything like my ’68 911 L?

I always wanted a street legal race car. I liked the 962 models that were street legal.

If this had retained the more factor like body it would have been perfect.

I have driven a couple race cars on the street and it is just a blast.

The story of this car got particularly nasty at the end with the Lawyers. It looks good with a bit of 959 at that back end.