Media | Articles

The Prinz and the astronaut

In American mythology, every NASA astronaut drove a Corvette. The heroes of the space race, lionized by the press, were seen as courageous and fearless under pressure, Alan Shepard deadpanning “Let’s light this candle” while waiting to launch. The Corvette fit the fighter-jock image, a group of former test pilots racing each other to the pad in America’s V-8 sports car.

John Glenn, the first American to orbit earth, chose something different. Like the other members of the Mercury Seven, Glenn was famously offered a $1-per-year Corvette lease by Jim Rathmann’s Florida Chevrolet-Cadillac dealership. But Glenn trundled back and forth to work in a thrifty little rear-engined oddity: an NSU Prinz.

Odds are, if you’ve heard of Neckarsulm Motorwerken AG, it’s in relation to the German firm’s rotary-powered Ro80 sedan. Built from 1967 to 1977, the Ro80 remains a handsome car—picture a midcentury BMW styled by the French—and in another universe, it might have established itself as one of the period’s great machines. Reliability issues dominated the model’s story, however, and the car’s mechanical troubles eventually led to the collapse of its maker. Late Ro80s were more dependable, but by that point, Volkswagen had acquired NSU and combined it with Auto Union to form the modern version of Audi.

Before its fall from grace, NSU was a vigorous company. As a motorcycle manufacturer in the early 1950s, the brand racked up four years of land-speed records. In 1956, in Bonneville, NSU racer Wilhelm Herz became the first person to ride a motorcycle at more than 200 mph. Then, in 1957, NSU produced their first postwar car, the Prinz. Advertising at the Frankfurt Motor Show boldly declared the appeal: Fahre Prinz und Du bist König. Drive a Prinz and you’re a King. If perhaps of modest means. Early Prinz models produced just 20 hp from a motorcycle-derived, 583-cc two-cylinder, though power rose to 30 hp by 1959.

The Prinz was imported to North America in small quantities by Max Hoffman’s Fadex Commercial Corporation, which also brought in the tiny BMW Isetta. According to one source, Glenn bought his Prinz from a Vancouver, B.C., dealer that specialized in unique marques.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

A Prinz is tight inside if not quite cramped. As a former test and fighter pilot, Glenn would have been familiar with tight quarters. A Marine, he had earned eighteen Air Medals and six Distinguished Flying Crosses while in service, one of the latter for achieving the first supersonic transcontinental flight. He was a veteran of Korea’s MiG Alley, where he’d downed three enemy jet fighters with his F-86 Sabre. In his 1979 book The Right Stuff, Tom Wolfe wrote that Glenn showed up to work in a Peugeot. Glenn read the work and sent off a correction letter, noting that his car was actually a Prinz. “I drove the Arlington to Langley run once a week or so,” he wrote, “all 180 miles of it each way. With my kids being a little older than some of the other [astronaut children] at that time, I was already concerned about their college $ [sic], so the Prinz seemed like a good idea. Don’t believe the Prinz is in production now—haven’t seen one in years—and good riddance.”

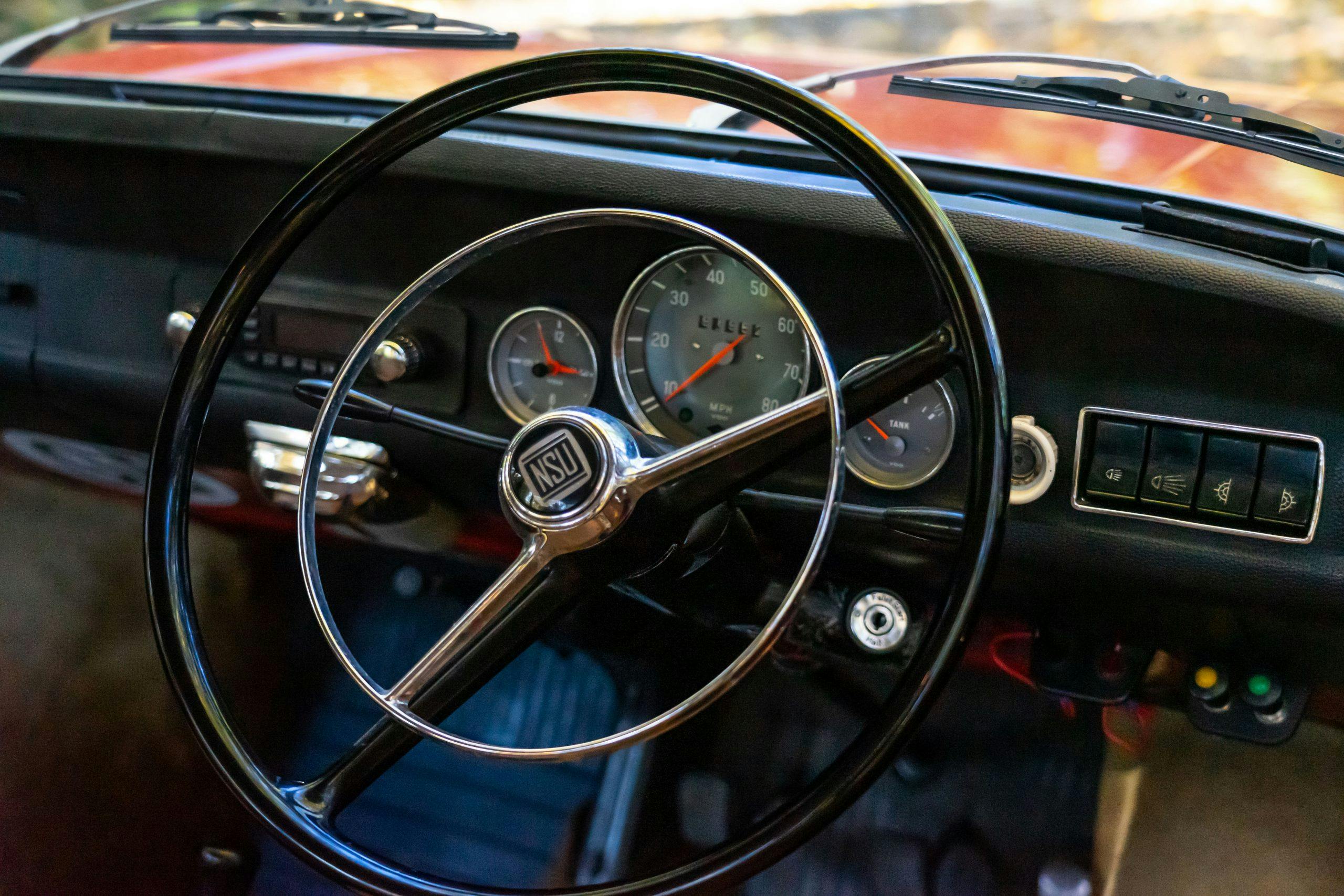

The Prinz would remain in production until 1972, eventually gaining a larger engine and even a bit of racing pedigree (more on that shortly). The British-spec 1971 Prinz 4L shown here belongs to Canadian Robert Talbot. Its 598cc engine still produces around 30 hp.

Talbot grew up in West Vancouver, BC, where a neighbor had a Prinz II. Trained as a horticulturalist, Talbot was working in England when he met a female friend who owned three NSUs. While the Prinz was something of a charming oddity in North America, the car’s fuel thrift and sensible layout made it successful in Europe. The model couldn’t quite match the contemporary Volkswagen Beetle for sales volume, but it held various regional sales records, such as being the top import into the Italian market.

Talbot calls his ’71 Prinz “Stella,” Latin for “star.” It was the second Prinz he bought while living in the UK.

“I used to drive from London to Somerset on a regular basis, and the 125-mile journey was only a bit faster in my modern car,” he says. “In a modern car, the temptation is to use the motorways, but which have a higher speed limit but tend to be full of traffic. Driving the NSU on A- and B-roads was a pleasure, and only about 30 minutes slower than [taking a] modern car on the [main] roads if they were actually clear of traffic.”

When Talbot decided to move back to Canada, he pondered the impracticality of bringing such a small car back home. But he’s glad he did.

“The Prinz is light enough that it is nippy around town, and it’s not my everyday car, so it doesn’t need to be very fast. I can keep up a surprising pace. Unless there’s a steep hill, most cars around me [probably don’t realize] there are only two cylinders and 30 hp under the lid.”

Thirty horsepower was enough for astronauts and horticulturalists, but NSU did bump power significantly for some Prinz models. Along with the 65-hp Prinz 1200 TT, the company offered the race-ready Prinz TTS, which made 70 hp from a screaming 1.0-liter four. In race trim, with mechanical fuel injection and high-compression pistons, a 1200 TT could make as much as 140 horses. Picture a West German version of a Fiat Abarth.

TT stands for Tourist Trophy, referencing the Isle of Man motorcycle road races in which two-wheeled NSUs competed. Decades later, Audi would resurrect the TT and TTS badges for a series of sporty small coupes, a tribute to the marque’s ancestry. But fierce little racing specials weren’t what the Prinz was all about. Instead, it was a people’s car, bridging the gap between the lightly impractical bubblecar thrift of a BMW Isetta and the real-world practicality of a Beetle. It still has a small but enthusiastic international fanbase.

John Glenn may have wished his Prinz good riddance, but we like to think he did so with faint affection. The man had nothing to prove, needing only the most pragmatic tool for the task of getting to work. For that job, at least, the NSU had all the right stuff.

John Glenn continued his rear-engined adventures with a 1961 Chevrolet Greenbrier and a 1964 Corvair Monza Convertible. All that remains of the Greenbrier is a photo of John standing in the driver’s side door, but his 1964 Corvair is still around – I’ve owned it since 2001 and fully restored it a few years ago.

I’m glad to see some recognition of NSU as a fine car manufacturer. My brother and I raced Prinz 1000 in C sedan at Riverside International Raceway in the seventies. My brother had these domed pistons that we tried to use in converting our motor to 1200cc. No matter how many times we shaved the pistons to increase the clearance and reduce compression, the engine would blow up.

As a footnote, in the 2010s our engine was still around, but nobody could make it work. Finally, it was converted back to 1000cc and ran flawlessly.