Media | Articles

The original Ford Mustang’s unsung hero

Proving that these are indeed bizarre times in the Motor City, Ford recently announced plans to end production of nearly all the traditional cars it sells in the U. S. That soft rustling sound you hear is Henry Ford, the father of mobility for the masses, spinning in his grave.

The Ford Fiesta, Fusion, and Taurus will soon cease to exist. The Focus will evolve into a Chinese-built pseudo-wagon called the Focus Active. The Lincoln MKZ will vanish, and the Continental luxury sedan will be sold mainly in China. Brooming these cars clears the path for Ford’s more profitable fleet of crossovers, SUVs, vans, and pickup trucks.

The Ford Mustang will be the only Ford car line to survive in its current form. Foreign buyers love the all-American pony car, demonstrated by more than 125,000 in sales last year across 146 countries. Next year, Mustang will supplant the Ford Fuson in NASCAR’s top tier Monster Energy Cup racing series. Street racing enthusiasts are licking their chops over the 2020 Mustang GT500, which is expected to join the 700-horsepower club with a supercharged and intercooled 5.2-liter V-8 under its swollen hood. Building Mustangs is a profitable endeavor for Ford, thanks in large part to its success topping Chevy’s Camaro and Dodge’s Challenger sales volumes.

20180508114559)

Birth of the Ford Mustang

Last month, the Mustang celebrated its 54th birthday. It made its debut at the 1964 World’s Fair at Flushing Meadows in Queens, New York, which also previewed color television, the picture phone, jet packs, a U.S. Royal Ferris wheel (which subsequently became a suburban-Detroit freeway spectacle), and scale models of New York’s Twin Tower buildings. Ford’s iconic $2368 Mustang 2+2 was the most tangible star. More than 400,000 were sold in its first year, an all-time record.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Mustang history books detail the story of how Lee Iacocca’s marketing genius resulted in the creation of the enduring pony car market segment. It’s Mustang’s pre-history—the who, how, why, and where of its origin—that’s virtually a trade secret.

The who is Philip Thomas Clark, born in Iowa in 1935 and raised in Nashville, Tennessee. Initially inspiring to become an MD, then later an aeronautical engineer, Clark abandoned those pursuits due to poor health. Instead he studied art via a correspondence course he purchased from the Sears catalogue.

Clark combined that meager education with his passion for automobiles to create some drawings he courageously submitted to Chrysler. The sage reply he received was that he had talent but needed further education for any chance of joining the auto industry as a designer.

The ArtCenter school in Los Angeles, California, accepted Clark’s application shortly thereafter, and he was admitted to that prestigious institution’s Automotive Design Department in the mid-1950s. While commuting between his home and school in California, Clark enjoyed sighting wild horses galloping over western U.S. plains. Their spirit and stamina left an indelible impression, because his vigor was lacking due to what was later diagnosed as kidney disease.

One of Clark’s ArtCenter projects was the design of an auto badge with a stallion galloping to the left. Logically, he titled his work Mustang and tucked the drawings into his portfolio. The Design and Transportation degrees he earned from ArtCenter in 1958 were instrumental in Clark winning a job at GM in 1961. He was assigned to work under illustrious Corvette and Corvair designer Larry Shinoda on prototype cars that GM intended to showcase at upcoming world’s fairs in Seattle and New York.

Ironically, the concept of a sporty car called Mustang had already been studied at GM, according to design authority Robert Cumberford, who was employed several years in GM’s Studio X. In 1956, he and several other designers worked on what amounted to a four-passenger Corvette. That investigation was prompted by fears that the two-seat ’Vette might be scrubbed due to insufficient sales.

Cumberford recalls that Mustang was one of several horse-related names considered—along with Palomino, Pinto, and Scout—for a sporty 2+2 model with a long hood and short deck. The project never gained traction and Cumberford left GM several years before Clark joined the company’s design staff. Cumberford theorized that the Mustang idea may have migrated to Ford in the hands of another Clark—Corvette advertising copywriter Barney Clark (no relative of Phil’s).

In early 1962, Phil Clark left GM after only nine months of employment to join Ford’s design department. The company’s Total Performance campaign had just begun exploiting every form of motorsports in hot pursuit of desperately needed younger buyers. Clark’s badge and Mustang nameplate won a warm reception and he began designing cars worthy of wearing them.

One such project was an attempt to use key parts from the front-drive German Cardinal, an economy car that Iacocca vehemently blocked from entry into the U.S. as a Falcon update. Clark penned a svelte open two-seater with a low windshield and a prominent Targa bar. During a studio tour, racer Dan Gurney voiced enthusiastic approval for these conceptual sketches. The brilliant British-born chassis engineer Roy Lunn suggested relocating the Cardinal’s 1.5-liter V-4 engine and four-speed transaxle to the mid-engine configuration that was then gaining momentum in Formula 1 and Indy cars. Prominent California fabrication shop Troutman-Barnes was commissioned to construct a steel-tube space frame and suspension hardware according to Lunn’s designs. In a mere five months, the project advanced from management approval to a running car suitable for public presentation. (Read more about the Mustang I here.)

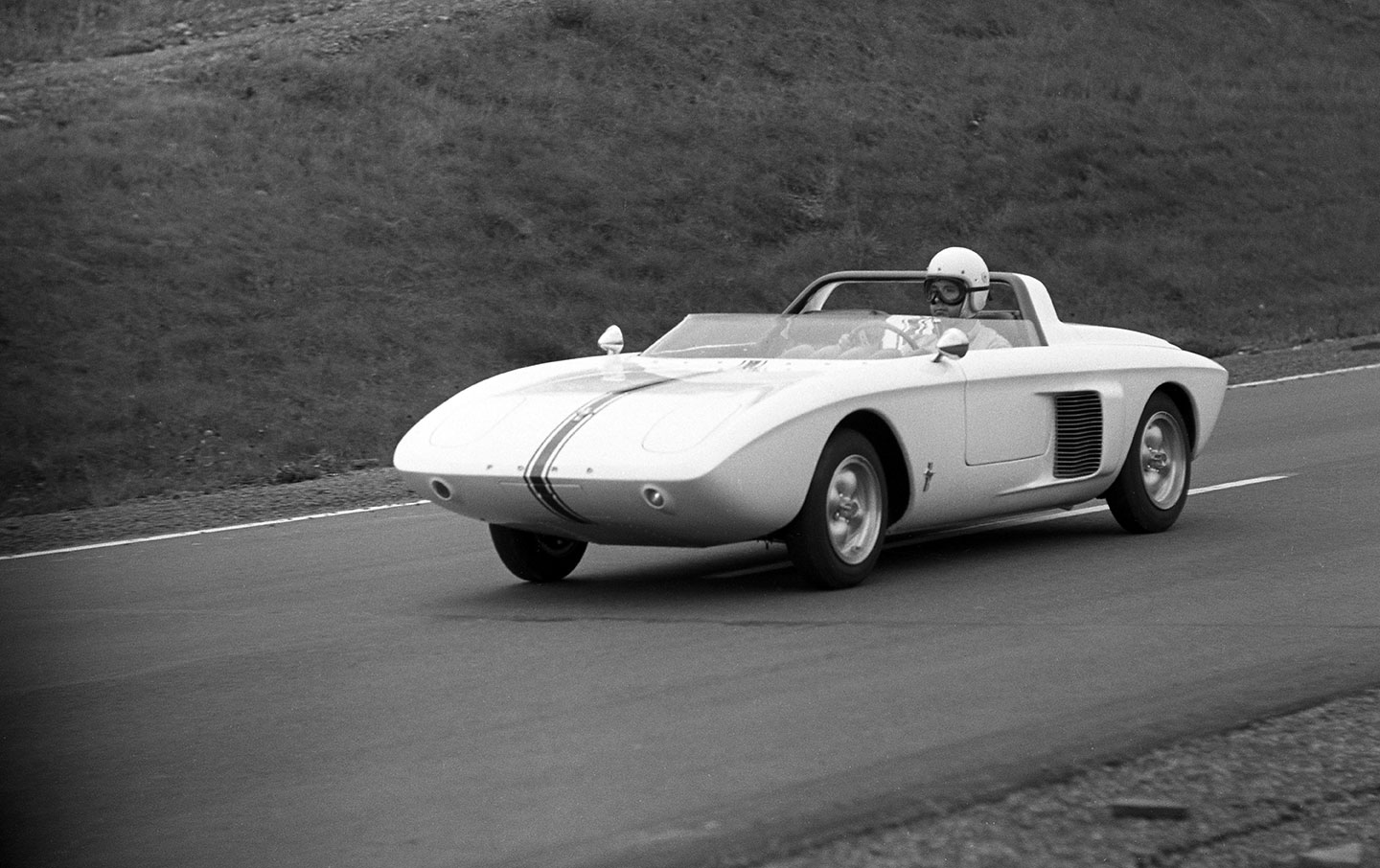

Clark’s key contribution was the badge centered on this sports car’s sloping nose: a galloping horse over vertical red, white, and blue bars, clearly branding it as an all-American stallion. The aluminum bodywork featured pop-up headlamps and side-mounted radiators cooled by electric fans. The leather-covered bucket seats were fixed in place while the steering column and pedals provided the necessary adjustability. The tiny four-cylinder was tuned from a stock 89 to a more palatable 109 hp with dual Weber carburetors, a higher compression ratio, and wilder valve timing.

The prototype Mustang I’s big splash

The original Mustang (later relabeled Mustang I to avoid confusion with the production 2+2) served as a spectacular opening act at the U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen, New York, in October 1962. A huge mural on its transport trailer celebrated the Mustang name and galloping steed logos. Gurney topped 120 mph while hot lapping the car before the main event.

Journalists who were offered brief test drives later bubbled with enthusiasm. Car and Driver rated the handling magnificent in “the first true sports car to come out of Dearborn” and “the most pleasant surprise of 1962.” This Mustang went on tour at car shows and college campuses galore in spite of the fact that Iacocca regarded it as only a placeholder for the more practical and profitable production car he planned for introduction a few months later.

In early 1964, just before the mainstream Mustang was born, Clark was transferred to Ford’s research and engineering center in Essex, England. A project code-named Colt was under way, and Clark immediately began contributing detailed drawings and clay models for what would become the Ford Capri. In 1968, production began in both England and Germany for what was marketed here as the Mercury Capri, a mate to the Ford Mustang. This was another huge hit, with sales topping 200,000 cars the first full year of production.

The Mustang I running prototype, which narrowly avoided a trip to the crusher, is currently owned by the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. Lunn, collaborating with the British race car constructor Lola, evolved its shape and layout into the Ford GT40 endurance prototype first campaigned in 1964. Following some epic initial stumbles, the GT40 became one of the most successful racers ever created; this Ford earned four 24 Hours of Le Mans victories in a row beginning in 1966.

Clark’s ill health finally caught up with him in early 1968, when he died of kidney failure. Without him present to confirm his rightful place in Mustang legend and lore, Clark’s name is not well known and his story is largely a trade secret. Fortunately, Clark’s daughter Holly has possession of his archives and drawings. She intends to set the record straight, appropriately highlighting her father’s role in the Mustang’s rise to pony car royalty.