Media | Articles

The Mazda Cosmo was a visitor from far, far away

In May of 1967, the ascendant Japanese automotive industry began producing what would become two of its most valuable and collectible cars. One of them, if we’re being blunt, was not nearly as interesting as the other.

There is much to love about the Toyota 2000GT, about which I have waxed poetic on this very website. The car’s elegant proportions, its role in establishing a longtime Yamaha-Toyota partnership, an association with the James Bond film franchise, the failed Shelby SCCA history—all of it remains compelling. In comparison to the other car that arrived that summer, however, the 2000GT is a rather conventional sporting GT. Another sports coupe was born in 1967, however, one that could have flown in from three million light years away in nebula M78.

Direct from tiny Mazda in Hiroshima, the Cosmo warbled into view with outlandish styling and an engine with zero pistons. Even today the Cosmo looks absolutely bonkers, so it’s difficult to overstate the impact of this car’s design in its day. Instead of the XKE-like, long-hooded silhouette adopted by Toyota for the 2000GT, the Cosmo was shaped like a spacefaring teardrop. It had a frog-like face and the rear bumper bifurcated the taillights, giving the whole car an alien aura.

While Toyota’s 2000GT would prove to be a bit of an evolutionary dead end, Mazda’s UFO arrived bearing technology that would excite and inspire an entirely new cult of engineering. The Cosmo wasn’t the first rotary-engined car, but it was arguably the most influential one to date; one can draw a straight line between this car and the piercing banshee wail of the Mazda 787B and its 1991 victory at Le Mans.

Beyond its connections to racing, the Cosmo arguably put Mazda on a path that gave the brand its fun-loving identity. This characteristic informed corporate culture at the company for decades. Just as there’s no Celica, Supra, or MR2 without the Toyota 2000GT, without the Cosmo there’s no RX-7 and probably no Miata. And without those cars, would it really have been Mazda at all?

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Let’s examine a snapshot at where Mazda was as a company when it took a gamble on rotary-power technology. At the time, the company’s sole passenger car was the tiny R360, which had fifteen horsepower and looked like a refugee from Richard Scarry’s Busytown series of children’s books. Mazda also produced commercial vehicles, including small vans and a series of three-wheeled trucks.

That Mazda was at this time building anything at all is pretty incredible. Just fifteen years earlier, Hiroshima had been largely destroyed by an American atom bomb, and there were still people walking around who bore keloid scars. By 1962, Mazda was producing the Carol—equally underpowered as the R360 but something of a commercial success in Japan. The previous year, the company had opted to license NSU’s Wankel engine for further development.

Felix Wankel had perhaps not the most savory background, having been once kicked out of the Nazi party for trying to make the Hitler Youth too militaristic. He also had no formal degree as an engineer, and never learned to drive owing to extreme nearsightedness. (Can’t make this stuff up. –Ed) Still, genius often strikes at random, and Wankel was successful in managing to take the idea of a rotary combustion engine from concept to working prototype while working for German automaker NSU.

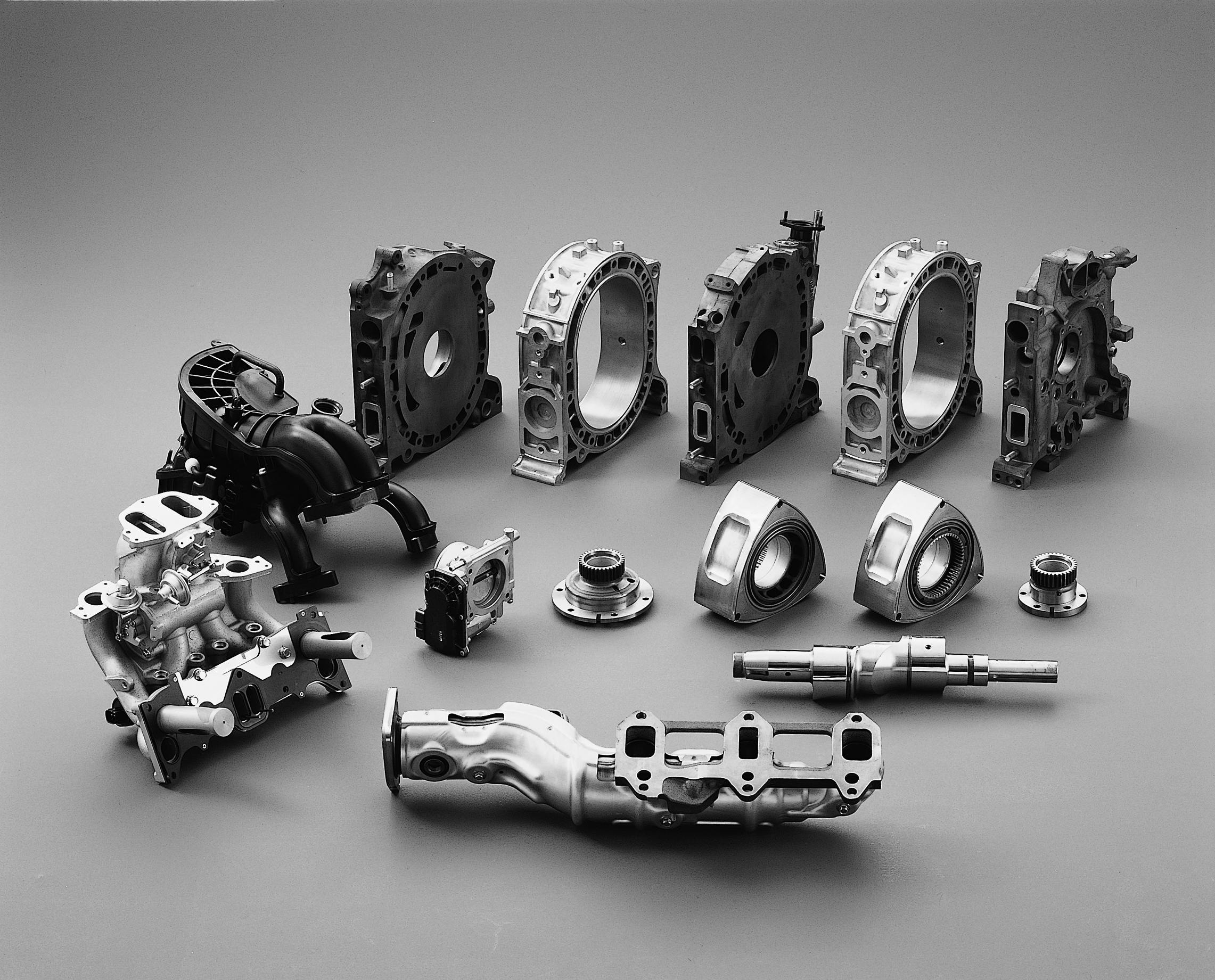

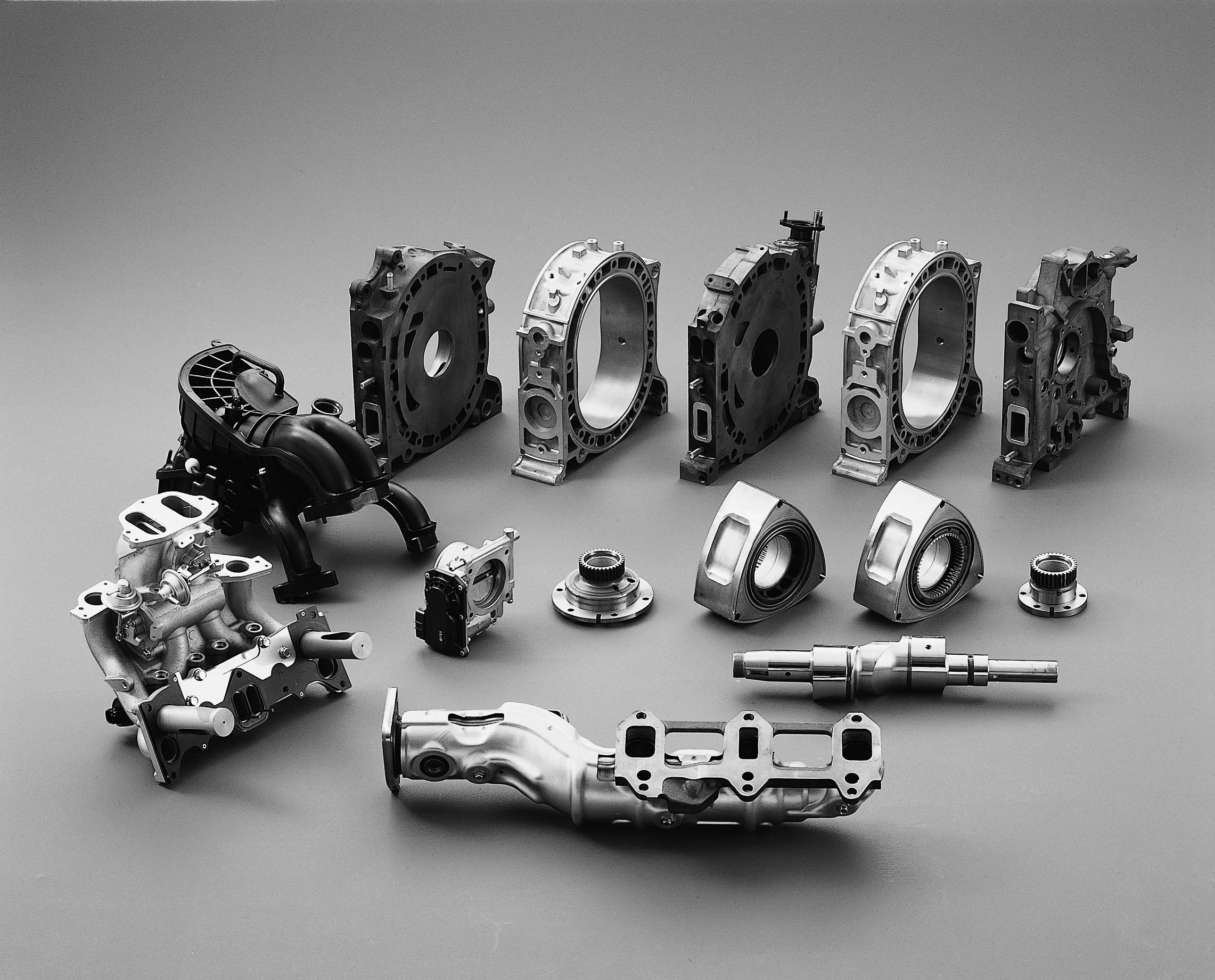

Really, history should assign more credit for the rotary engine to a fellow NSU engineer named Dr. Walter Froede. It was Froede who took Wankel’s complex and delicate design—both the rotor and the rotor housing rotated – and came up with a more conventional layout where the rotor housing was fixed in place. Without Froede’s input, the rotary engine might have been little more than an internal combustion footnote.

Wankel moaned that Froede had, “turned my race horse into a plow mare,” but the fact was, both prototype engines still had hooves of glass. Dozens of manufacturers tried to make the rotary achieve its potential, from Isuzu to Mercedes-Benz, and nearly all of them failed. Though theoretically lighter, more compact, and simpler than a conventional piston engine, early rotary engines were plagued by vibration and apex seal failures.

At the time, Maxda president Tsuneji Matsuda, son of the company’s founder, had two big problems. The first was the Japanese government’s consolidating approach to the automotive industry, which was forcing smaller automakers to fall under the control of larger ones. (Nissan acquired Prince and Toyota took over Hino, for example.) If Mazda was to survive, it needed a signature technology to set it apart. Problem two: The rotary engine didn’t work.

Enter a young engineer called Kenichi Yamamoto. Formerly an assembler of Mazda transmissions, Yamamoto had hauled himself up to an engineering position at Mazda by improving overall production quality of the line while he was working on it. He was naturally gifted, and he understood the stakes. Matsuda placed Yamamoto at the helm of a team of forty-seven engineers working on the problem of solving the rotary engine’s tendency to score its housing with rotor chatter. The team called itself “the forty-seven rōnin,” after the famous tale Chūshingura and the exploits of doomed warriors stripped of master and purpose. They would not, could not fail.

The rōnin threw everything at the problem, going as far as actually fitting animal bone as rotor tips. Persistence was the key—Mazda was fighting for survival here, not looking for a way to improve profitability. Eventually, solutions arrived: hardening the combustion chamber and adding oil to the fuel-air mixture.

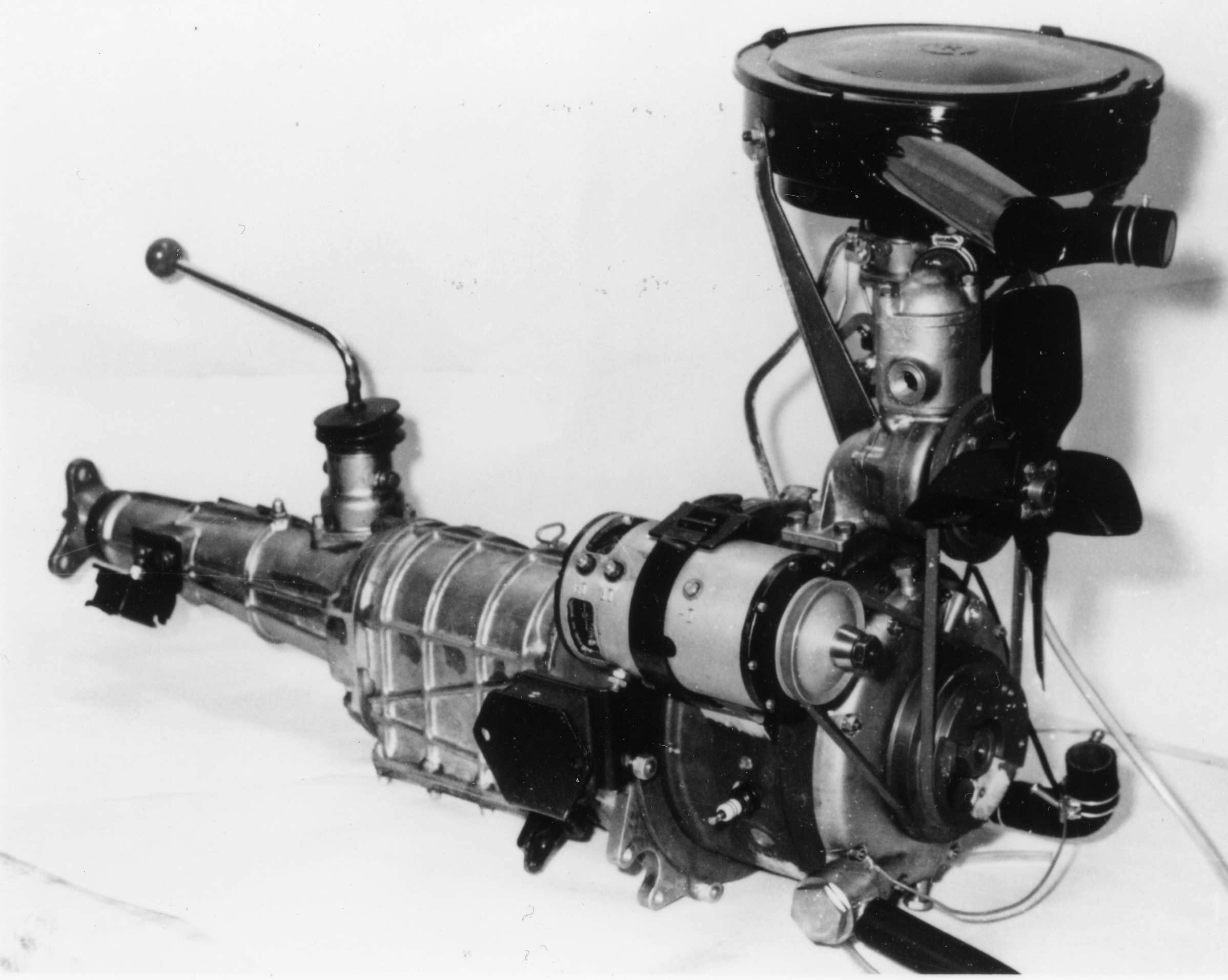

The twin-rotor L8A was Mazda’s second prototype Wankel, the one that worked. Freed up by its compact shape, designer Heiji Koayashi was able to pen a cab-centered design that was entirely unlike the classic long-hood short-rear appearance of other sports cars. A prototype Cosmo was shown at the 1964 Tokyo Motor Show, the same year that Japan hosted the Olympics and launched its first bullet train.

Success through engineering became core to Mazda’s culture, especially when Yamamoto became president of Mazda in the mid-1980s. From diligent line worker to innovative engineer to running the company, his rise mirrored Mazda’s fortunes. Pretty much the first thing he did was to approve the development of the Miata. A good call, to put it mildly.

Production of the Cosmo began in 1967 with the Series I Cosmo Sport 110 S (export models were called simply 100S). Like the 2000GT, each car was hand-built, and Mazda only managed to produce an average of one per day. The early short-wheelbase cars numbered only 343 made in 1967 and 1968, though a second production from 1968 to 1972 (the Series II, with 128 hp) saw a further 833 longer-wheelbase cars made, making the Cosmo overall less rare than the Toyota.

But an early car like this one is an exceedingly rare sight, let alone one that actually gets driven regularly. This 1968 Series I has been extensively restored, including the recreation of some extremely hard to find parts: replacement hubcaps, for instance, are completely extinct.

Horsepower is a reasonable for the era at 109 hp but, like all rotaries, torque is basically non-existent. The rotary spins with a characteristic warble and is turbine-smooth. Visibility is excellent and the houndstooth pattern on the seats has real charm. Even though this car is narrower and has a shorter wheelbase than a first-generation Miata, the cockpit is less cramped than the 2000GT.

And, whereas the Toyota found itself on the international silver screen, the Cosmo found fame at home in a smaller format. It was the hero car on the extremely popular TV show Ultraman, specifically Return of Ultraman. You know the type of thing: human actors in monster costumes stomping through a miniature cityscape. A 1971 Cosmo featured as the patrol vehicle for the quick response Monster Attack Team. The car looked weird enough to work.

The Cosmo also kicked off Mazda’s rotary racing heritage with a successful outing at the improbably grueling 84 Hour Marathon de la Route, held at the Nürburgring. One of the two-car effort retired with axle issues, but the other raced for three and a half days with no issues, finishing fourth in a crowd of Porsche 911s and Lancias.

As a boutique car with a racing pedigree, the Mazda Cosmo is worthy of status as Japan’s second-most-collectible car. And yet, it still doesn’t quite get the respect it truly deserves. It’s easily overshadowed by the 2000GT, and in terms of outright values (Good-condition examples bring $102,000, on average), the likes of the Nissan Skyline GT-R or Fairlady Z432 often fetch bigger dollar amounts.

However, it’s hard to think of a Japanese car that’s more fascinating than the Cosmo—in looks, in technology, in heritage. It is though a visitor from a far-off planet landed in Hiroshima one day, its mission to save Mazda and impart the blessings of unmuffled rotaries screaming around racing circuits. A car fit for Ultraman, at the very least. We count our lucky stars that the Cosmo entered the world’s orbit all those years ago.