Media | Articles

The Case for the Countach: Lambo’s bad boy seeks redemption in the Rockies

Victor Holtorf is on a mission. The Fort Collins, Colorado, proprietor of High Mountain Classics, a restoration and vintage race-prep shop at the foot of the Rockies, wants people to know that the Lamborghini Countach is a great car.

That’s it, just that: The Countach doesn’t suck. In fact, before we visited Holtorf and his personal collection of Countaches, he sent over a lengthy email covering Countach history that began with his objectives for our visit. “1) Educate the collector car public about this icon,” it said. “2) Correct myths and misconceptions about the car. 3) Have fun with friends.”

OK, you have to know Holtorf. He’s got one of those brains that naturally sorts the chaotic world into neat, orderly silos of logic and purpose, which is a valuable trait that explains how he came to own a bunch of Lamborghini Countaches (as well as dozens of other interesting cars). And you might dismiss his quest as an amusing bagatelle, like pleading the case for cookie-dough ice cream—especially to anyone whose first exposure to the car was watching Adrienne Barbeau and Tara Buckman streak across the desert in a black LP400S in that glorious Countach advertisement from 1981, The Cannonball Run.

If you saw that film as a kid, you’re entitled to wonder why the Countach—last year celebrating its 50th anniversary—even needs a defense. Holtorf was himself one of those kids, as well as one of the millions who subsequently tacked a Countach poster to his wall. That exact same poster now overlooks the lobby of High Mountain Classics, and he pointed to it when recounting how he bought his first Countach, an early LP400 “Periscopio,” back when they were about 75 grand for a nice one. It’s why he’s acquired three more, and why he’s made his shop—a second career after a fruitful first one in real estate—a refuge for broken and abused Lamborghinis.

However, as much as Holtorf loves the Countach, the car’s stature has unquestionably been dragged down by unsavory tropes. By its casting as the absurd clown car of the gold-chained, coke-dusted 1980s. By its reputation for routinely generating four- and five-figure shop bills for owners who don’t understand the car and don’t know how to drive it properly, and who are bled dry until they scream, “Enough!” and send their rejected plaything to the nearest auction, there to be fobbed off on the next star-struck pushover with more money than brains. And the Countach has been buried by endless magazine stories and by the internet echo chambers that repeat the same tired orthodoxies: that the Countach is brutal, that it’s hard to see out of, impossible to work on, and pretty much unusable as anything other than erotic garage sculpture.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Holtorf was so eager to stick pins in these widely held notions that he tossed us the keys to three examples for a romp in the rolling hills near his home. We set forth at dawn’s early light, an Italian air raid of sorts on the Colorado hinterlands, powered by 36 cylinders breathing through 120 valves and wailing out a combined 1285 horsepower. What we learned over two days is that Holtorf has a case: The Countach is indeed a great car. It goes and stops and turns and dazzles a crowd with outlandish abilities that were unknown in any other road machine of its era—and which are perhaps even more thrilling in the all-electrified, push-button, pull-paddle, 128-gigabyte reality of today.

That is, as long as you fit in the car, can get it started, and don’t slip the clutch too much because it’s easy to fry the clutch—and it costs 20 grand to yank the engine out and replace it. “These are high-speed toys,” allowed Holtorf, “and if they are not treated accordingly, they will cause problems, but that is not the car’s fault. It’s driver error in poor planning and execution.” Sure, you can do a quick kombucha run in a McLaren 720 without having to worry about yanking the engine afterward, but is that really living?

When Mick Jagger sang that he was “born in a cross-fire hurricane,” he could have been referring to the Lamborghini Countach. It arrived after the golden years of Automobili Ferruccio Lamborghini were behind it, right as speed limits, inflation, regulation, and a worldwide energy crisis bore down on the auto industry like so many flaming Molotovs. A Countach was the first Lamborghini to die against a crash-test barrier. It suffered the ignominy of grafted-on bumpers and choking emissions controls. The workers who built at least the first ones were on strike so often that the company’s own founder and namesake, Ferruccio Lamborghini, walked away in disgust before the Countach reached full production. Its chief engineer and test driver followed soon after.

Yet, miraculously, in a world where sequels are rarely as good as the originals, Lamborghini was able to follow the breathtaking Miura with a car so shocking and louche that it came to overshadow its predecessor and define both the company and the exotic-car game for the 16 years it remained in production. About 2000 Countaches left the Lamborghini plant at Sant’Agata Bolognese, more than twice the number of Miuras. Into the 1980s, new Countaches rolled out of the factory against practically insurmountable odds, weathering Lamborghini’s repeated ownership changes, its eventual bankruptcy, the onset of catalytic converters and computerization, and nearly two decades of fashion flux among the mercurial arrivistes who craved it.

It didn’t seem possible that such a bonkers machine could survive for so long as I contemplated the skyward-pointing driver’s door on Holtorf’s well-worn 1975 LP400. Holtorf bought this early Countach in 1992 when he was living in the Bay Area and, seeing no reason to do otherwise, raced it at local club meets. On racetracks. With other cars. Apparently, back then you could go wheel-to-wheel in anything at some events so long as you wore a helmet—no cage or five-point harnesses required.

One day at Thunderhill Raceway Park, a rollicking ribbon about an hour and a half north of Sacramento, Holtorf became the salami in a race-car panini that left scars gouged in his Lamborghini’s millimeter-thin aluminum body. He applied Bondo and a spritz of primer and called it a day—actually, a couple of decades, as that was more than 20 years ago and Holtorf has been driving the car with its primer patches ever since (though he long ago retired it from racing).

I assumed the position, taking Holtorf’s direction to plant my butt on the Countach’s wide sill, then slung my right leg over the sill, followed by my left leg. From there, you easily slide in, like a bullet clicking into a chamber. The car’s two leather chairs look like wave chaise longues that contort your body into one non-adjustable rocket-sled position (the seats do slide back and forth). The shape and square-patterned tufts are surprisingly cushy and comfortable, despite what magazines said at the time.

Space inside these early Countaches is at a premium; the flat roof is ridiculously low, the center tunnel hilariously high, and the foot pedals are mere millimeters apart. The small, thin-rimmed steering wheel is, like those of most Lamborghinis of the period, situated for gorilla body types—meaning people with short legs and long arms—and with non-simian-shaped humans, it lands just inches from the knees. A few cryptographically marked rocker switches and some rotary knobs suffice as the car’s lighting and climate controls. The instrument binnacle is a mail slot sporting a line of miniature Stewart-Warner Stage III gauges that look like they were selected from a 1960s mail-order racing catalog—except for the analog odometer on the 320-kph speedometer, which instead of displaying its numbers horizontally is oriented vertically, like an old hotel marquee on Broadway. It somehow seems the most exotic thing about the LP400’s interior.

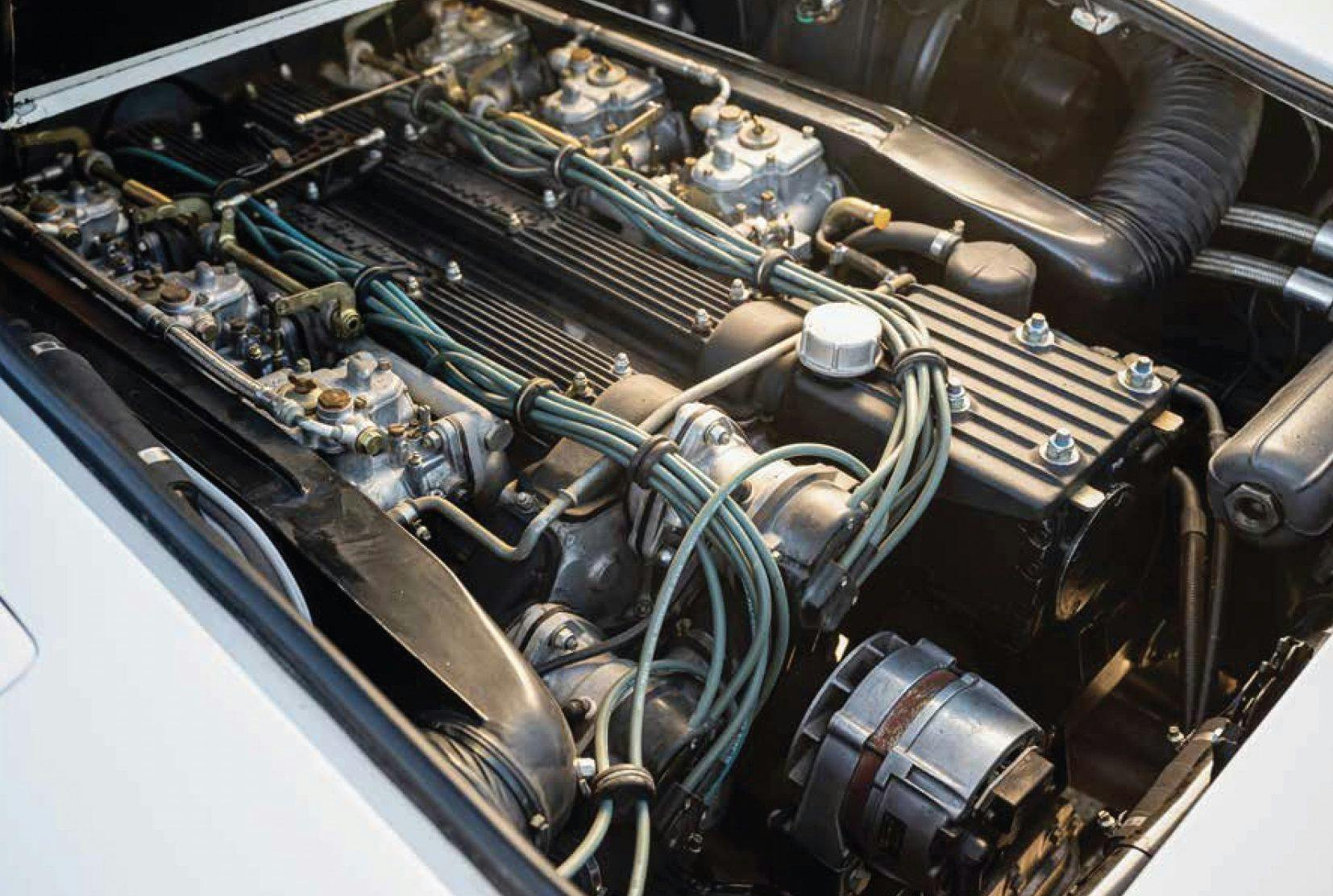

The V-12 at our backs fired immediately after the frenetic whirring of the starter, and the car moved off on a surprisingly light clutch. You have to lean on that gas pedal, however, against the drag of a long cable tugging on a bell-crank-and-pushrod affair that cracks open the throats of the six Weber 40DCOE, or doppio corpo orizzontale E, carburetors. The horsepower and torque all live at the top end of Bizzarrini’s 8000-rpm cathedral organ, so there’s no point in shifting early. The revs rise not to a deep, booming baritone of a large-bore engine, but to the ripping tenor vibrato of a relatively small but many-cylindered mill, that euphonious intake snarl from those 12 velocity trumpets hiding in the airboxes behind your head.

You have a lot of time to soak it in because first gear is so long. “Back then,” explained Holtorf, “ Lamborghini and Ferrari were trying to outdo each other in 0–60 times, so first gear is tall so you can go past 60 without shifting.” That explains why so many owners go through clutches so quickly, immolating obscenely large piles of Ben Franklins in the process. Baby a Countach clutch if you want it to last, insisted Holtorf—repeatedly. Which means planning in advance where you are going to drive the car so as to avoid stop-and-go traffic and clutch-frying parking ramps. “It’s like an airplane,” he explained. “You have to flight plan with a Countach or you’re going to have problems. You can’t just jump in it and go to dinner somewhere you’ve never been before.” None of this disqualifies the car for greatness, in his opinion.

Though the Countach is no quicker than a modern Mustang GT, its howl and drama in full rage is one of the motoring life’s divine experiences—especially in this, the purest of all Countaches. At speed, it feels like a Lotus Europa stuck on the nose of an F-16, an intimate capsule with surprisingly light controls and an entirely unexpected eagerness to dive into corners with neutral balance. This isn’t the brute I thought it would be. When I shared these observations with Holtorf, he simply nodded. It is what a Countach does when it’s maintained and set up as the factory intended. Lamborghini may have been a house on fire in the mid-1970s, but they still knew what they were doing.

Paolo Stanzani, who had come over from the firm’s tractor business in 1963, had taken Gian Paolo Dallara’s place as Lamborghini’s technical director when Dallara bailed in 1968. Involved in turning the company’s venerable four-cam, 3.9-liter V-12 sideways in the Miura, Stanzani in 1971 proposed rotating it yet another 90 degrees to face backward. Instead of the Miura’s frame of box-section welded beams perforated by weight-saving holes, Stanzani chose for its successor a pure race-car spaceframe of welded steel tubes, which would be lighter, stiffer, and—worth mentioning considering the time and place—easier to rustproof.

Turning the engine in alignment with the car’s center axis and slotting the transmission between the seats would centralize the engine’s mass better than it had been in the Miura and move some weight forward to the front axle, even if the propshaft running aft through the sump would raise the engine slightly. Instead of placing the radiators up front, as in other mid-engine cars such as the Miura and Ford GT40, Stanzani wanted them off to the sides, thus allowing a dramatically low nose and better forward visibility.

The basic concept was handed to Bertone to see what could be made of it. Nuccio Bertone had been Ferruccio Lamborghini’s closest collaborator and booster. His Turin design house and its styling chief, Marcello Gandini, had taken up the challenge of the transverse mid-engine Miura in 1965 with obvious relish. At the time, Bertone saw Lamborghini as a potential counterweight to the indomitable Ferrari, and Bertone’s burgeoning relationship with the tractor magnate as potentially yielding the greatness and riches that the long association with Ferrari had done for Pininfarina.

Building on the global plaudits for the Miura, Bertone envisioned a more angular, folded-paper future for sports cars in the late ’60s with a string of “hyper-wedge” design concepts. They included the Alfa Romeo Carabo of 1968, an impossibly low, emerald-green shingle with prescient scissor doors, and the 1970 Lancia Stratos HF Zero, which, at 33 inches tall, barely rose as high as the average cowboy’s belt buckle. Into this wedgy stew was thrown the Project LP112, Lamborghini’s internal designation for its Miura replacement.

However, by the early 1970s, Nuccio Bertone had lost his enthusiasm for Lamborghini, whose founder proved less dedicated to beating Ferrari than growing wine on his vineyard near Lake Trasimeno in central Italy. Bertone was also souring on his gifted protégé, Gandini—who, because of the Miura and other successes, was developing both international acclaim as well as a cocky attitude toward the boss. Nuccio figured it was only a matter of time before Gandini, like his predecessor, Giorgetto Giugiaro, would leave to open his own firm (in fact, Gandini stayed until 1980).

These intramural fissures are highlighted by the fact that the Countach, one of Gandini and Bertone’s most universally recognized designs, is barely mentioned in the carrozzeria’s two-volume boxed history by Luciano Greggio. “I remember that Stanzani, the engineer, asked Gandini to design the flanks specially so that the radiators could be mounted laterally,” recalled Nuccio Bertone years later for the book, sniffing, “the result was interesting, but not beautiful. Rather it looked like an attractive girl with her nose a bit crooked; people were more interested in the door-opening system than anything else.”

Perhaps, but one Bertone metalworker assigned to the team building the first full-scale mock-up—and who spoke the language of his native Piedmont region that encompasses parts of northwest Italy, France, and Switzerland—was moved to repeatedly exclaim, “Contacc!” It was basically the equivalent of “wow” or “dang,” and the word, with slight phoneticizing, stuck.

With no advance fanfare, Lamborghini and Bertone debuted the Countach LP500 concept at the 1971 Geneva motor show. The reception was uproarious. Ferruccio Lamborghini, whose heart really lay in building big, comfortable GT cars for, as he put it, “serious guys,” was once again compelled as he had been with the Miura to put into production a two-seat psychedelic road burner “for crazy guys.” The thinking was that the company might build only a handful, with no air conditioning or other creature comforts, for a select few fanatics who were already good customers (how many times in recent years have we heard the same said about limited-production hypercars?). Even Ferruccio saw the car as something of a throwback, recalling for an interviewer in 1980: “I said to myself: This is going to be the last chassis coming direct from the racetracks, the last birdcage frame. This time is past.”

But Ferruccio couldn’t refuse the money being thrown at him by the crazy guys. In 1972, without warning, the Bolivian government defaulted on a huge order for Lamborghini tractors. That and a canceled order from America left 5000 finished units sitting in yards with no customers. The ensuing cash crunch forced Ferruccio to sell off his beloved tractor company as well as 51 percent of his carmaking operation to a Swiss businessman, Georges-Henri Rossetti. He was seen even less around the plant, where union militancy had become so intense that production frequently ground to a halt. According to one account by the late Claudio Zampolli, an engineer at the time, leftist agitators slashed tires in the parking lot and lobbed missiles through the windows at the salaried front-office staff still at their desks. Ferruccio finally unloaded his remaining stake in 1974 to retire to his vineyard. “When I was still building Lamborghinis,” grumped Ferruccio a few years later, “people were talking about women and cars—maybe about football. Nowadays, they talk only about football and politics. The women and automobiles went into oblivion.”

He left Stanzani, the remaining engineers, and New Zealand–born test driver Bob Wallace to make the LP500 a viable car that wouldn’t melt its engine. It was a challenge given that Gandini’s original concept offered precious little in the way of a cooling strategy. Another problem was that the designer apparently had not given any thought to rain. After trying various unsatisfactory wiper solutions, Stanzani settled with pasting on a single large wiper arm with primary and secondary blades to sweep the sprawling glass. Then he resigned, walking out shortly after Ferruccio and shortly before Wallace quit, too.

From concept car to assembly line, the Countach sprouted NACA ducts in its flanks and scoops on its shoulders. Nevertheless, Gandini’s vision remained largely intact, except that there had been no time or resources to develop the proposed all-digital dash or the 5.0-liter V-12, the reason for the original LP500 designation. The 3929-cc V-12 that had served Lamborghini so ably since 1965 was sent into the breach yet again, meaning the production Countach would carry the designation LP400. Turned backward, the all-aluminum 375-hp mill put just 266 lb-ft of torque to the five-speed transmission between the seats. Still, it was an audacious design from a tiny company with extremely finite resources, and the core powertrain layout was to serve the Countach for its entire production run, as well as its replacement, the Diablo, and the Diablo’s successor, the Murciélago.

Only 150 of the first series LP400s were built, and the best ones go for over a million dollars now. With their skinny Michelin XWX tires, uncluttered lines, and small roof cutout intended for better rearview visibility (hence the “periscope” or “periscopio” nickname), they represent the closest thing to the original blueprint of the Countach’s creators.

Holtorf happily pointed out the differences between the various Countaches. After the first LP400, Lamborghini’s remaining engineers took note of some performance mods done by one of their favorite customers, Canadian oil-drilling-equipment mogul Walter Wolf, as well as the development of the new Pirelli P7 high-performance tire. To fit the new, wider P7s, the Countach sprouted flares packing deep “phone-dial” magnesium wheels patterned after those on the 1974 Lamborghini Bravo concept car. These and a detuned 350-hp emissions model, explained Holtorf, were the so-called LP400 S “low body” models, now highly sought after as the poster Countaches we all know and love.

The darkest days were in 1980, when Lamborghini was under court-controlled receivership after a series of disastrous management schemes. Plenty of plutocrats wanted a Countach, but Lamborghini was so short of money that its two oldest distributors, EmilianAuto in Bologna and Achilli of Milan, offered to pay cash for cars in advance so there would be enough money to pay suppliers. It wasn’t clear whether the few loyal Lamborghini employees and acolytes left were saving the Countach or if it was saving them.

In 1981, the factory was flush with fresh capital from a new owner, the Swiss Mimran family, which had built a generational fortune in Africa from sugar farming. Lamborghini raised the car’s roof by 2 inches and jacked up the suspension, all in anticipation of—at last!—sales in the U.S. Until then, the car had been locked out of that lucrative market because the company lacked the resources to federalize it. These so-called “high-body” Countaches had five-hole OZ alloy wheels, often painted gold, and were a little heavier and slower owing to the larger body and emissions controls. The high-body cars also initiated the Countach’s long, sad battle with U.S. bumper regulations; the various solutions developed by the factory never looked any better than rhinoplasty gone awry.

The Countach’s second wind—literally—came with the development of a 4.7-liter V-12 in 1982, followed in 1985 by the 5.2-liter Quattrovalvole. The four-valve engine finally took full advantage of Giotto Bizzarrini’s original decision in 1963 to flout Ferrari’s then- standard of single overhead camshafts and instead design Lamborghini’s first V-12 with four cams. Horse-power in the Countach jumped to 455 in the European carbureted version, which replaced the sidedraft Webers of the previous models with racier downdraft carbs. A federally compliant version with Bosch K-Jetronic fuel injection was rated at 425 horsepower.

Holtorf’s carbureted black 1988 5000QV, with its gold rims and archetypal rear wing scything the air, is pure schoolboy fantasy. The QV is identifiable by the humps in the engine hatch (one hump for carbureted engines, two for U.S.-spec fuel-injected versions), and the “Quattrovalvole” badge on the rump. These high-body cars indeed offer more space inside even as the seats and basic goony ergonomics remain largely unchanged from the original LP400. The interior is altogether more deluxe in the QV, although there is a wider deployment of plastics, as befitting a car from the 1980s.

Maybe it’s me, but the additional weight and rubber on the road seem to counteract the benefits of extra horsepower, though the torque off idle is distinctly stronger as the enlarged engine takes bigger gulps of air. Testers who suppressed their mechanical sympathy to extract 5.6-second runs to 60 mph in the original periscope Countach—nearly a full second quicker than the contemporary Ferrari 365 GT4 BB—returned to find the QV could do the deed in about five seconds flat on its way to a 180-mph top speed (the later Ferrari 512 BB and BBis were also quicker). It was a blinding acceleration figure in the 1980s.

Again, the QV chassis has a certain grace to its movements even if the steering is much heavier at lower speeds owing to the fatter front tires. Holtorf explained that the suspension doesn’t use conventional rubber bushings but racing-type uniball and heim joints with plastic inserts to reduce friction. Over time, these wear out and impart a rattly looseness to the ride and handling that many drivers mistake for bad or antiquated engineering.

Which is why owners who take their cars in for something minor are so often presented with unexpectedly gonzo repair estimates. If the mechanic is willing to do the whole job (many aren’t, or can’t), he’ll walk the owner under the car and demonstrate how the sloppy joints clank and twist as the wheels are tugged. From there, the bills rain down like hellfire. “Worn joints, plus fat sticky tires, usually past their replacement dates, cause lousy handling in poorly maintained cars, which is most cars,” said Holtorf. “As do incorrect aftermarket shocks, worn weakened coil springs, and other changes. Stock is always best.”

And then there is the 25th Anniversary model, which commemorates not the model anniversary but that of Lamborghini’s founding in 1963, and which one magazine described as looking like a QV that had been “dragged through a J.C. Whitney catalog.”

An unfair characterization, perhaps, as the Countach can’t be faulted for keeping up with the neon-lit, permed-hair, acid-washed, spandex-shod fashions of its moment (and all the strakes and filigrees very much make it of its moment). The restyling was attributed to work done by Horacio Pagani, who later founded his own car company but was then a Lamborghini employee who developed new composite materials and fabrication techniques.

The Mimrans were probably the only investors ever to make money on Lamborghini, as they bought it for only $3 million and unloaded it to Chrysler in 1987 for $25 million. To recoup its investment, Chrysler immediately stepped on the gas, and Countaches poured forth from Sant’Agata in previously unheard-of volumes. About half of the total number of Countaches ever made were built in the last three years of its existence.

Holtorf’s own black Anniversary was down with a problem, so one of his customers, Stephen Tebo, kindly stepped in with the superb, low-miles white one photographed here. The modernization is all too apparent in the digital stereo and climate-control displays. No doubt Chrysler chief Lee Iacocca thought manual windows and seats were a crime in a car priced at $225,000. But the new and bulky power buckets robbed the cockpit of both its distinctive original couches plus whatever extra space was afforded by the shift to the high body in 1981. The seat controls, behind a flip-open panel in the sill, barely adjust the seats, moving them just a few short inches, but at least they are adjustable.

Everything seems heavier in the Anniversary, partly because the whole car is, since it gained almost 600 pounds during its long life. Yet it’s definitely quicker, even if you need to hold the wheel and shifter as though they’re attached to a rodeo bronc. It seems like all the Countach clichés stem from the Anniversary model, as it’s less initially friendly than the periscope and even more demanding of compromise than the QV. Perhaps it’s simply that by 1988, it seemed silly to buy any car with a shoebox trunk and footwells sized for the soles of children. But then that is often the case with cars left in the market too long: They age out of their moment of newness and novelty and get saddled with equipment they were never meant to have.

There’s no question that the Anniversary is an exhilarating brain fry that sucks down superlatives as quickly as its 32-gallon fuel load. You develop a rapport with it over time and begin to think maybe—just maybe—you could drive this thing to work, maybe a couple of days a week while the electronic climate control maintains a perfect 72 degrees and the stereo belts out Joan Jett.

And yet my mind kept drifting back to the periscope, and how badly I wanted to take it home and love it. It’s ridiculous, absurd! A piece of 50-year-old art with crotchety mechanicals and bodywork so thin that to lean on it is to damage it. Access to the V-12 is effectively through a ship’s porthole. You need weird, four-prong socket wrenches to do any serious work. You need special oil, special water, probably special air for the tires. The QV has a better suspension, and the Anniversary is better still, benefiting from experience and investment dollars from Detroit. And most people would agree that a Miura is more classically beautiful.

And yet. That original origami vision—so mod, so kinetic, so lurid. If it had, as Bertone said, a crooked schnoz, it was the crooked schnoz of the century.

To Holtorf’s point, the Countach is a great car. It was when it debuted as the last-of-an-age lightning flash out of Italy, a chin-flick and vaffanculo! to all the self-appointed guardians of virtue who were laboring so righteously to legislate the end of fun and freedom. And the Countach finished strong, still leaving the boombox burghers slack-jawed at the curb. In no universe that we know of can it be used as ordinary transportation. The Lamborghini Countach is pure hedonistic, licentious, nihilistic entertainment. As we all know, that is usually the best kind.