Media | Articles

Tesla, modernism, and the endless pull of tomorrow

Across the digital world, most published content is bite-size, designed for quick consumption. Still, deeper stories have a place—to share the breadth of an experience, explore a corner of history, or ponder a question that truly engages the goopy mass between your ears. Pour your beverage of choice and join us for a Great Read. Want more? Have suggestions? Let us know what you think in the comments or by email: tips@hagerty.com

When the railroad tracks came into view, my foot reached for the brake pedal.

“No,” Don said. “Go fast as you want—we’ll see it and hear it, but we won’t feel it.”

I downshifted into second, asking the grumbly French engine for full throttle. The Citroën’s sixty-year-old chassis rode eerily level. I winced sympathetically, tightening my grip on the wheel. By the time I glanced down at the speedometer—65 kmh, about 40 mph—it was over. We had coasted over the tracks as if they weren’t there.

I looked at Don, the owner. At his raised, told-you-so eyebrows.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

That night, in another car, the magic continued. A Tesla drove me to my hotel while I barely lifted a finger. There was little fanfare, just the glow from the Model 3’s tablet screen and the soft hum of drive motors. The car negotiated tight curves in the road and waited patiently for oncoming traffic at an intersection. Matting the accelerator unleashed a wallop of torque. Or I could take the wheel and huck over the back roads myself, savoring the 3’s balance and response.

“Pretty cool, right?”

Gene, in the passenger seat. In addition to serving as Hagerty’s community coordinator, he is the Model 3’s owner and this website’s resident Tesla evangelist.

“I’m bullish on Tesla,” he said, “but even I don’t think all cars will be self-driving any time soon.” He stared out the window, letting the thought hang in the air. “Then again, I didn’t think unmanned rockets would ever land themselves on platforms in the middle of the ocean.”

***

What separates great cars from ordinary ones? Why do some transport us while others are mere transportation?

In a word, personality. The idea that a machine can somehow connect you to a greater feeling, especially when that feeling is tied to a cultural moment. And when a car truly taps into the zeitgeist, people flock to it.

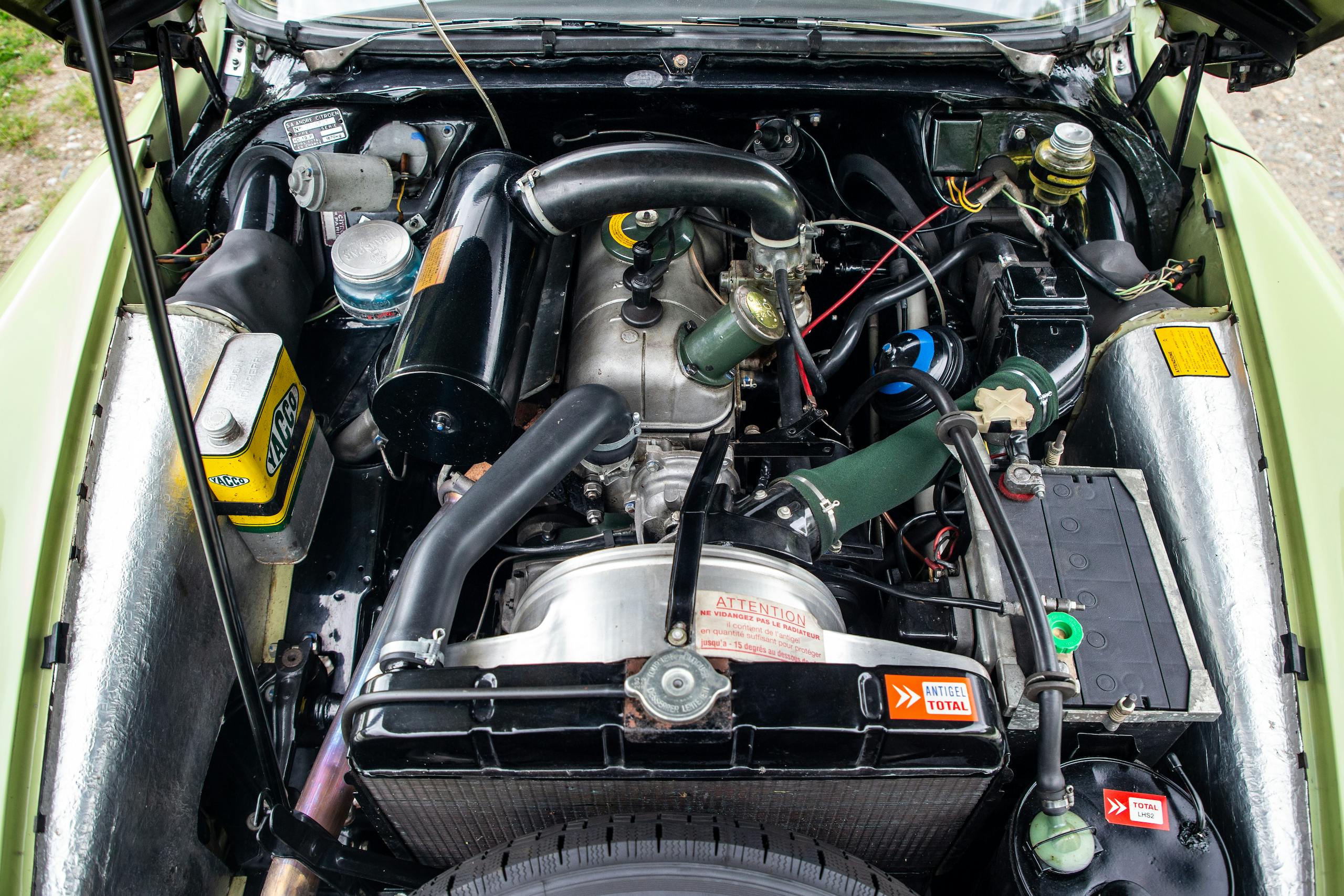

In 1955, that car was the Citroën DS. It debuted in Paris, at the city’s then-annual motor show—a space-age streamliner in the cultural capital of Europe, seemingly from a distant and more sophisticated place. The design was almost nautically curvy, a refutation of the past. The rear turn signals lived high on the C-pillars, near the fiberglass roof. Entire panels could be removed with a handful of bolts for easy service. The independent suspension, brakes (inboard discs in 1955!), and steering were all power-assisted, run off a central hydraulic system. Pressurized mineral oil flowed through tubes, pumps, and rubber bladders, giving the car load-leveling ability and variable roll control but also active anti-squat and anti-dive.

The engine sat longitudinally but drove the front wheels, obviating the need for a transmission tunnel and freeing up cargo space. The gearbox was a downright alien, hydraulically powered automated manual with a column shifter and no clutch pedal. Even the brake pedal was different—a pyramid-shaped rubber mound with only a few millimeters of travel.

Little about this car lined up with the world’s idea of how an automobile worked. Nor was it just for the elite. While the top-trim DS19 came with every bell and whistle, the ID19 version that arrived in 1958 was meant for the common man. Retaining the DS19’s suspension but resorting to unassisted steering as well as conventional brake and gearbox systems, the car cost $2833, just under $30,000 in modern dollars.

“The DS19 was the luxury car of France, the car de Gaulle drove,” Don told me. “By contrast, the ID19 was [a] Ford Fairlane—comfortable, roomy, adventurous. And while American cars were like jukeboxes … the DS was built like an airplane.”

From the outset, Citroën envisioned the DS as a new kind of car, for a new, modern world. The project reflected an idea that had been gaining momentum for decades: technological progress as a way to better humanity. In the 1940s, this meant destructive power; after the war, it meant blessing ordinary lives with inconceivable grace and convenience.

With the DS, for thousands of people, one look was enough. Citroën secured 12,000 pre-orders by the end of the Paris show’s first day. Ten days later, there were north of 80,000. The record set by those pre-orders went unbroken for 61 years. Until Tesla.

No 21st-century carmaker has so quickly and utterly altered the course of the industry. After more than a decade in business, Elon Musk’s start-up has sold more electric cars than any other automaker. Tesla’s skateboard-style battery pack has inspired dozens of imitators. Its Supercharger network includes more than 31,000 individual chargers around the world. At this very moment, every major car company on planet Earth is feverishly trying to beat Musk at his own game. Not a single one is even close.

Tesla bills the Model 3 as entry-level, smaller and with less range than the company’s revolutionary Model S. When the Model 3 opened for pre-order in March of 2016, at a starting price of $35,000, more than 180,000 people laid down a $1000 deposit. After a week, 325,000. The Tesla quickly became something most modern carmakers would kill for—a genuinely cool and genuinely desirable EV with upper-middle-class appeal and unmistakable identity.

More important, Musk has for years managed to bypass conventional marketing, harnessing social media to spread his gospel. In doing so, he won a militant fanbase that continually trumpets his crusade.

Gene, our Tesla owner and a recovering Corvette obsessive, is one of those believers. “All the best gas cars have come and gone,” he said. “This is the future.”

***

The Model 3 and the ID19 are separated by more than six decades, but the impact of each draws from a deeply human concept: The idea that humanity is on a continuum to … somewhere. World peace? Enlightenment? Life eternal? Whatever’s at the end, most of us want to believe it is worth chasing.

People rarely think so big-picture. We think even less often about the ordinary stuff filling our days—college sports, a tea kettle, whatever—and how that stuff cannot be divorced from the meaning that we have assigned to it over time. Take the Dodge Challenger. The shape suggests an appreciation for muscle machines and a golden era of American automotive supremacy. The Dodge conveys that idea in its proportions and details but also in its visual menace; the car is a myth made alive, at work in the world today. You see the car, you understand it.

In 1957, just two years after the Citroën debuted, cultural theorist and philosopher Roland Barthes wrote an essay collection called Mythologies. Each entry in that collection unpacked so-called myths of French society. Red wine, for example, wasn’t simply the poisonous consequence of grape juice left out too long; as Barthes saw it, the liquid was life-enriching nectar, a national beverage appreciated by rich and poor alike.

Wine isn’t inherently those things, of course, but that description mirrors how the French have grown to understand and mythologize it.

Barthes recognized that the DS was more than just a new luxury car. In Mythologies, he kicks off a dizzying rant on the car with the following:

I believe that the automobile is, today, the almost exact equivalent of the great Gothic cathedrals … a great creation of the period, conceived passionately by unknown artists, consumed in its image, if not in its use, by an entire populace … an entirely magical object.

Pompous and academic, yes, but it hits on a basic truth: We build monuments to access the divine. If the Gothic cathedral was Christians physically reaching for the heavens, Barthes argues, the DS was the reverse: a car seemingly descended from above.

Different though they may seem, the Model 3 holds the same basic appeal. As new cars, both the Citroën and the Tesla are attractive and practical for their era, an everyday driver for an affluent buyer. For a technologically inclined person eager to communicate a message: I am in the know, on the cutting edge, among the first to taste the future. Today we call these people “early adopters.” For a certain set, a new car like a DS, an ID, or a Model 3 is a status statement, the profession of an arguably moral imperative: Ditch your dated Detroit barge or gas-guzzling SUV and embrace inevitable progress. In 1950s America, Citroën’s marketing slogan was, “It takes a special person to drive a special car.” If Tesla has a slogan now, it’s on the “About” page of the company’s website: “Accelerating the World’s Transition to Sustainable Energy.”

No matter where you sit politically, no matter how technology advances, you probably hold general belief in progress as known good. In a society more secular with every passing year, this is perhaps the closest we come to a modern version of shared trust in a higher power. The cathedrals simply look different.

***

In ancient Greece, Aristotle often discussed the concept of telos—the fulfillment of purpose. In mid-century France, the DS didn’t merely evoke the heavenly with its shape; the name itself invoked divinity. The French pronounce the car’s two-letter name as déesse—the French word for goddess. Lofty, too, was the ID model, or idée, idea.

Barthes latched onto this motif in typically highfalutin fashion:

It is well known that smoothness is … an attribute of perfection because its opposite reveals a … human operation of assembling: Christ’s robe was seamless, just as the airships of science-fiction are made of unbroken metal.

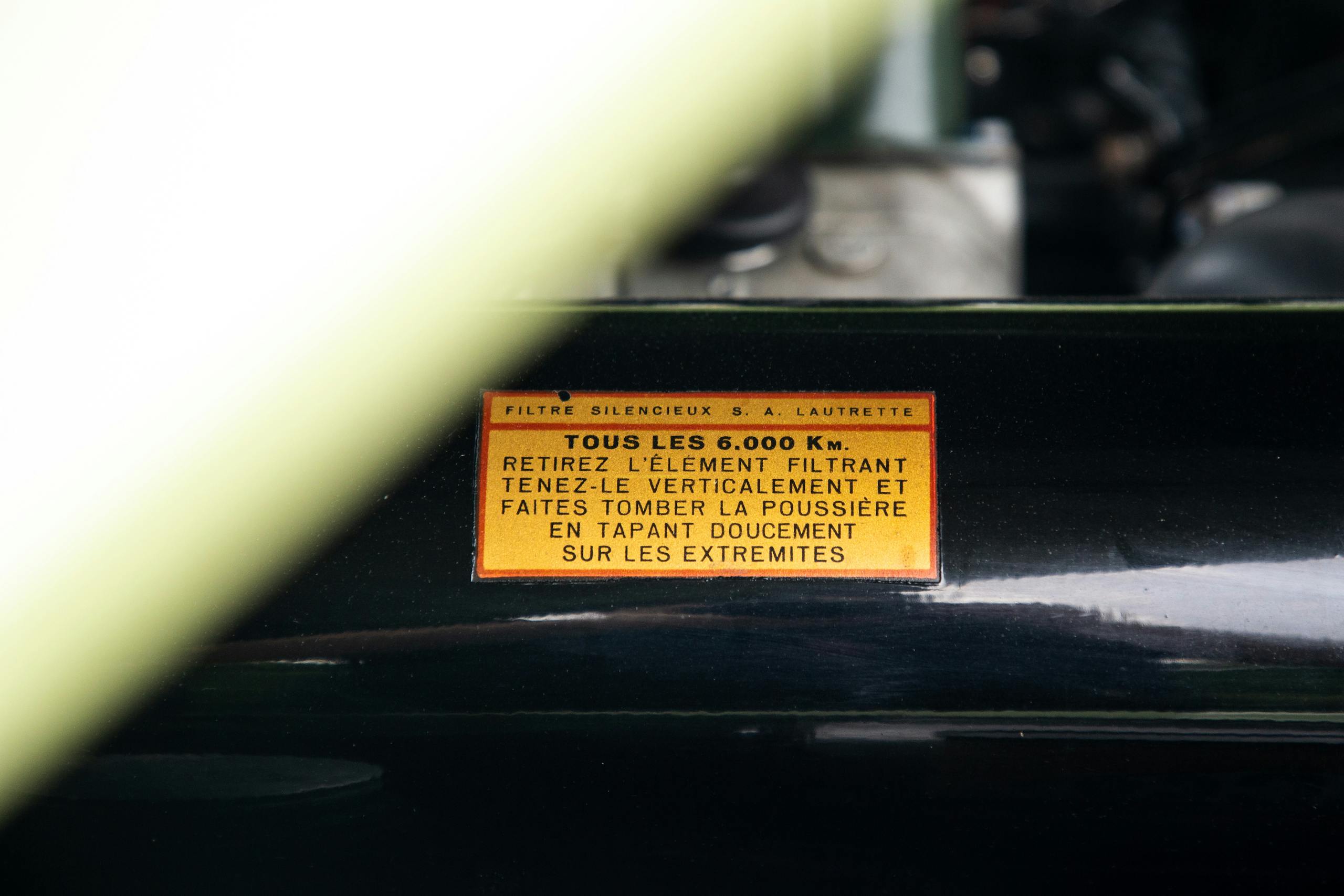

Good design often means disguising the imperfection of the human hand. The devil is in the details, as the idiom says. Where the DS wore expensive chrome trim and eye-catching touches, the ID was the shape reduced to its essential form. Don’s car, shot and driven for this story, is proof: The roof is unpainted fiberglass. The interior is vibrant but unfussy and filled with daylight. The door panels are rimmed in body-color plastic, their inserts built like the seats, synthetic fabric stuffed with foam. The instrument cluster is basic, just three gauges.

Even leaving the car requires a piece of remarkable design efficiency—the latch release on the interior door handle doubles as the lock switch, moved easily with a thumb. Then there is that famously oddball steering wheel, one central spoke, an unbroken circle.

If designer Franz von Holzhausen’s crisp, flowing Model 3 recalls the seamless geometry of Apple’s iPhone, the connection is surely intentional. Apple’s sleek smartphone reshaped the world as we know it. Will Tesla do the same? The Model 3 relies deeply on this persona of purity and lightness, with its zero-emission powerplant and futuristic brand identity. A panoramic glass panel runs the full width of the roof, making the cabin feel open to nature. The interior is hyper-clean, clinical even, minimalist and sparse. There isn’t even a traditional instrument cluster behind the steering wheel. Information is delivered solely through that center-mounted tablet screen. Essential functions can be accessed through one of the wheel’s two spinning-ball selector buttons, positioned on the spokes for easy thumb use.

As in the Citroën, the lack of a transmission tunnel allows for impressive interior space and console storage. Door pockets are large and useful. Materials feel high-quality but not necessarily luxurious. Leaving the Model 3 also means a door opened by a button, in this case, electronic.

It’s a strange reminder that, regardless of how far we seem to have come, people still ride around in metal boxes with wheels and doors. Has so much really changed?

***

Western society has been on this industrial hamster wheel for longer than we like to admit. Modernist thinking is rooted in the 19th century, and Barthes’s essay notes that history is woven into the fabric around us. As he put it, the DS wasn’t a clean-sheet vehicle, but one tied to old notions from science fiction:

The Deesse is first and foremost a new Nautilus.

As in the submarine. Jules Verne wrote 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea in the late 1860s. Nemo, Verne’s anti-imperialist antihero, captains the Nautilus, which he designed himself. The ship is meant to work in harmony with its environment. Power comes from rechargeable batteries fed by the sodium in seawater. The crew is sustained by ocean plants and animals. The ship is luxurious, with an extensive library, a pipe organ, and instrument displays in the captain’s quarters. The latter exist so Nemo can monitor the sub’s progress without physically commanding its movements.

Sound familiar? A convention-flouting battery-electric vehicle that can operate without the captain’s direct control?

20,000 Leagues was wildly popular when new. Like a lot of Verne stories, it began as mass entertainment but was quickly held up as a possible future. The DS, for its part, took off in Europe and ultimately sold more than a million examples globally over 20 years of production. When the car was discontinued in 1975, Citroën did not follow it with another revolutionary moment. Moreover, the company spent the next half-century trying, and failing, to reach similar heights.

This is where our narratives split. The Model S and Model 3 share both a parts bin and a CEO, two home runs from the same bat. Odds are not against Tesla producing more cars that capture the public in the same way, if only because of how Musk operates. For all its flaws and strengths, his car business is merely means to an end, an offshoot of a worldview rather than the view itself.

Musk’s direct-to-consumer sales model feels fresh and transparent to customers exhausted by the traditional American dealer experience. When he blows a deadline or a big promise, his uncanny lizard brain for hype spits out pie-in-the-sky concepts like the Cybertruck and the Roadster. Finally, there is, of course, SpaceX. You don’t see GM or Ford sending people into space, beaming free internet into Ukraine with satellites, or teaching rockets to land themselves.

In other words, when modern people imagine the future outside the automobile, the Model 3 seems like a piece of it they can own. Fruit from a larger tree.

***

Great cars give you an experience you didn’t know you needed. At Citroën, the DS and ID replaced a model called the Traction Avant. That car looked like a 1930s gangster taxi and was more difficult to drive. Don’s ID is classic momentum car—not quick, but capable of brisk pace if the driver plans ahead. As in an old Volkswagen Beetle, you cannot rush shifts, and engine speed is determined by ear and feel—there is no tachometer.

Stranger still is how you don’t ever feel the car working. The suspension is the center here, soaking up enormous bumps and smoothing body motions without calling attention to itself. The Tesla is so different. It is the proverbial cruise missile: powerful, immediate, and always primed for launch. You sit far forward, almost over the front wheels, the tip of a spear. Tap the tablet to adjust the front-rear torque split, dial up regenerative braking, or change steering weight—the software changes things immediately. The Model 3 feels hard-wired to your commands, but there is no give and take, no conversation between driver and machine. The car simply executes.

In spite of that—and this is especially fascinating—the Model 3 is satisfying to drive. Much of the Tesla’s immediacy and balance recalls classic sport sedans. That character was not essential to the car’s success, but it counts all the same. It lets the Tesla serve as a sort of bridge, appealing to enthusiasts and performance people like Gene as much as to tech junkies who see cars as appliances.

If the Citroën and Tesla are easy to love, it is because they are optimized for everyday life. They seem to acknowledge that the world outside the car matters. The DS must have felt like such an oasis when new—bright and airy, a sharp handler but eminently comfortable, plenty spacious for a family of four. The Model 3’s wide trunk and low load floor makes it genuinely practical. The Tesla phone app tells you when your cabin has reached a pre-programmed temperature, so it’s ready for your morning commute. Want to sleep in your Model 3? Order a custom-made mattress online and go right ahead: The battery can run all night with minimal strain, automatically maintaining a comfortable temperature. That large console screen can play video games and movies or browse the internet with the speed of a smartphone.

For whatever reason, the Citroën inspired few copycats. Other automakers admire the Tesla’s inventiveness but cannot seem swallow pride and surrender infotainment design to Silicon Valley.

That’s the thing about myopia—when you have it, you can’t see past it.

***

For all the mythmaking, these are merely cars. Engaging with them demystifies them; you can’t head to work in a self-landing rocket or use a submarine to pick up your kids from school. The Citroën and Tesla feel unique because they tell stories about who we think we are and who we want to be, regardless of whether those stories are true. Most of all, they represent the thrill of rapid change. Of leaving something behind to chase the better, or even just the different.

Once we reach that horizon, we think, we’ll be different, too.

“Myth is neither a lie nor a confession: it is an inflection,” Barthes said. Behind the wheel, when everything is right, the future can seem just around the corner. Always ahead, magnetic in pull, and yet forever out of reach.