Media | Articles

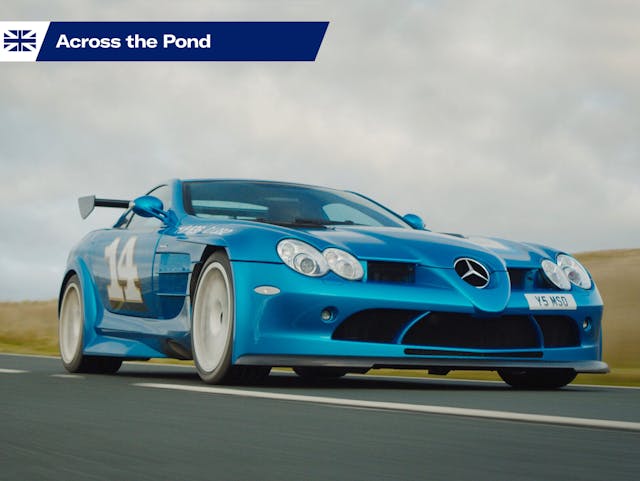

Taming the “new improved” McLaren SLR HDK

Sometimes you have to know when not to be a road tester. When you should leave your mental checklist at the door and just be a car enthusiast. You need to remember that as important as objectivity is, occasionally the subjective can be enough. It’s ok for heart to rule head. The SLR HDK is a case in point.

When the standard Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren was launched in 2003, after the debut of the Vision SLR concept car in 1999, there was a lot of head scratching among the press. For a start, there were conceptual hurdles to overcome, because with McLaren and, more specifically, Gordon Murray involved everyone had expectations about how this might follow in the lightweight tire tracks of the F1 supercar. As a result, a 1600-kg (3527-pound) car with a supercharged engine and power assistance for almost everything came as something of a shock. The SLR was not the rival for Porsche’s Carrera GT for which I think most were hoping.

Even if you were able to look past this, the way that the car drove was … interesting. The brakes, for example, appeared to have no progression at all and the chassis felt like the front and rear were speaking different languages. Not great when you’re trying to deploy 617 bhp and 575 lb-ft through the rear wheels, and thread a near-two-meter wide car along a road.

Aesthetically it was a striking machine, but the proportions meant that junctions could be tricky, to say the least. Never has the phrase “nosing out into traffic” been more appropriate. And although the exterior had a wild theatricality to it, the interior was a curiously humdrum hodgepodge of Mercedes parts bin switchgear. It was like a penthouse furnished with Ikea Billy bookcases.

As a road tester given a few hours with an SLR at its launch, I can see how it was probably not much more than a three-star car. So, why is it looked upon with so much affection by owners today? Enough affection for a dozen of them to get on board with McLaren Special Operations for a crazy project like the HDK (and you can be sure that most, if not all of the owners will be adding the new kit to an existing SLR in their collection).

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The HDK, which stands for High Downforce Kit, is effectively an evolution of the SLR performed by the team at McLaren Special Operations. With input from those SLR owners, it sets out to pay homage to the 722 GT, a prototype SLR racing car that never raced. We’ll come to the various changes in a moment, but what you should know is the package costs a not inconsiderable £280,000—about $346,000, or as much as an SLR—which tells you a lot about where owners of SLRs find themselves in life, and how they treasure the supercar enough to continue to refine it almost two decades on.

After a few days and many hundreds of miles driving an SLR HDK, I get it. This is a car that is very easy to love when you accept what it isn’t and enjoy what it is. For a start, there is the soundtrack. The glorious V-8 gargle has always been a highlight of the SLR thanks to its crazy side-exit exhausts that vent somewhere near the soles of your feet and gently vibrate your legs’ marrow from bottom to top. This is particularly the case in the HDK, which swaps two exhaust tips per side for big single, slashed pipes. The standard car’s huge silencers that weigh 15 kg (33 pounds) each have also been replaced by lighter, freer-breathing items. Add in a dash of supercharger whine every time you crack the throttle and you have a fabulously characterful aural recipe.

Some 20 years on, the interior has aged surprisingly well, too. With the new carbon transmission tunnel and the full carbon rear deck behind the seats, MSO has added a welcome amount of freshness to the overall ambience. Reclined in the fixed-back seats—trimmed, in this car, with some mustard corduroy that looks freshly culled from the scene of a pheasant shoot—it’s easy to find a decent driving position as well. And that starter button hidden under a flip-up cover on the gear selector never gets old.

Speaking of which, the gearbox is a less obvious source of delight. You can try to use the paddles on the back of the steering wheel but you’ll give up quickly, leaving the HDK’s jaunty shift lights permanently unlit. The five-speed automatic is just so slow to respond that it’s not worth the trouble. Better to leave it to juggle ratios itself and rely on the huge reserves of torque to dig you out of any holes.

But despite this, the gearbox is, curiously, crucial to the SLR’s appeal. Its very aloofness makes the car feel relatively undemanding and therefore surprisingly usable. With just two pedals and no paddles to worry about, there isn’t too much to concentrate on. The proportions of the proboscis require some thought and the brakes (despite the best efforts of MSO) still need care, but otherwise it’s quite stress-free.

So, you have the drama of a supercar but less of the angst. And as a car in a collection, I can absolutely see why owners might grab the keys to their SLR on a more regular basis than other, five-star supercars. Still interesting, still some thought required, still raises a smile, but not so much pressure. The value probably isn’t even too concerning for most of the people that own one. Even if you’ve spent £280,000 on a conversion, I suspect most would probably rather leave an HDK on the street than a Porsche Carrera GT.

Not that this HDK version wouldn’t attract attention. In Dinoco blue, with hand-painted numbers (each one is really quite different when you start looking) it definitely has even more of the Instagram wow factor than the standard car. And yes that is gold leaf—hand-turned with a piece of velvet to get the machined look.

The HDK letters first appeared on a handful of McLaren F1s. This SLR doesn’t actually have a huge amount of downforce by modern standards, but if you open the boot, you’ll see that the rear wing isn’t just for show because the struts go all the way through to the chassis, providing potentially the most over-engineered curry hooks along the way.

The main reason for the wing, however, is aesthetics because this HDK has been produced to pay tribute to an SLR called the 722 GT—a prototype race car that never raced. It was designed under Gordon Murray’s watchful eye and took all sorts of bits left over from ’97 F1 GTR race cars. Its purpose was to convince suits in Stuttgart that the SLR should go racing, which worked, although the race series came much later and the cars (built by RML) were never quite as spectacular as the original.

So the HDK is an homage. An exacting one at that, with a huge amount of meticulous work done by MSO to cut carbon and then graft on more, so that it looks as though it was always thus. To my eyes, the end result improves on the original SLR shape. The extra 60 mm of width give a more muscular stance, but the new sills somehow reduce the visual weight of the car at the same time.

Power is up by an insignificant 10 bhp, thanks purely to the better breathing through the exhausts, and torque remains the same, but it doesn’t exactly feel like more is required. The suspension takes all the tricks that MSO learned with earlier special editions but also adds some compromise. For example, although it is three seconds faster around the McLaren test track, it could have been four seconds faster, but that would have involved softening the ride and reducing some of the race car feel. And given that this is a car that is fundamentally about character, not competition, concessions were made in the final spec of the KW dampers to keep it feeling more like a race-track refugee.

But although it is firmer and flatter and a little more raucous than the original SLR, it also rounds off the edges just enough to retain that crucial sense of being a Super GT. It tramlines and it feels very connected to the road, but I found I could easily do hours at a time behind the wheel, draining the twin fuel tanks. When you find a good piece of road, the HDK won’t reward like the best drivers cars, but you’ll certainly find it holds your attention. MSO has tamed some of the handling, but push hard and you’ll find that the SLR HDK can intimidate with the best. Those brakes still require real thought, too, and the rear reacts with … but there I go being all road-testery again.

All you really need to know is that the HDK is a supercar that makes you smile, from the moment you see it to the moment the bombastic exhaust note dies away. As someone described it to me, it’s like a daft family Labrador. Not likely to win any agility or obedience prizes, but deeply lovable.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

Why would they not put a period after the second letter in HP and CI? It looks silly just saying “H.P” and “C.I”. Acronyms do not require a period unless they spell another word actually.

They could have just wrote “HP” and “CI”. I’d you add periods, add them after both letters. LOL

BTW, I ensure my classic car with Hagerty. Great company!