Media | Articles

Sorting out fact from fiction in a 1987 BMW M3

So much has been written about the original BMW M3 that it’s hard to separate fact from fan-fiction.

Strip away the myth, status, and collectibility that surrounds it and you’re left with just another boxy-looking product of the 1980s. It’s a double-breasted power suit of a car with wheel arches that look like beefy shoulder pads. The wheels seem too small. The whole thing is hard to take seriously—like two kids stacked on top of each other inside a trench coat. This can’t really be a race car, can it?

Rise to the top

But all that’s ’80s is new again. The first-generation M3—chassis code E30—is very much back in fashion. For proof, just look at the astronomical prices an E30 M3 now commands.

“Over the last five years, only four cars that we cover in the Hagerty Price Guide have seen a value increase larger than the E30 M3,” says Andrew Newton, Hagerty’s auction editor.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

“HPG condition #3 (Good) values are up 315 percent over the past five years.”

The big spike in value came in 2015, Newton adds, with prices for condition #2 cars (Excellent) now at more than $85,000. A low-mileage example sold on Bring A Trailer for $102,000 in January.

Clearing up muddied waters

Because of the E30 M3’s rapid rise to collectible status, everybody suddenly has a hot take. The cars are either overrated, overpriced, brilliant, the best-ever BMW, or proof-positive the entire classic car market suffers from a bad case of groupthink.

Amidst the amateur punditry and maddening prices, it’s hard to be objective about the car at the center of it all. But we’ll try—for posterity, or because we’re curious, or something.

When a man from BMW Classic fires up a bright red (Hennarot) 1987 M3 from the company’s collection in Munich and hands you the keys, just try to stay cool. It’s impossible. You will go full fangirl, stare too much, smile like an idiot, and snap a zillion photos.

This particular M3 has only 29,017 kilometers (18,030 miles) on the odometer. It’s as pristine a 1987 M3 as exists anywhere in the world. It’s been babied by factory mechanics. Best not to think about how much it must be worth, but… $150,000 perhaps?

The door opens with a hollow clack. The cockpit is much the same as any other E30, which is to say, plastic. As often happens with this generation of 3 Series, the dashboard is slightly warped above the central air vents. The sport seats don’t reach up to my shoulders. The leather-rimmed steering wheel has no adjustment. But the tall gear lever for the five-speed dogleg gearbox feels perfectly placed.

Birth of a legend

The story of the first M3 will be familiar to many enthusiasts, but briefly, BMW needed a race car so it could open up a can of wüppsie on rival Mercedes’ new 190E Cosworth. So, the regular 3 Series coupe was transformed into the homologation-special M3, a race car for the road. The plan worked; the M3 raked in 1500 victories and remains the most successful touring car of all time. Fettled by U.K. outfit Prodrive, it even managed a decent rallying career.

BMW built roughly 18,000 M3 road cars between 1986–90, according to figures from BMW Registry.

In West Germany, in 1987, this M3 cost $59,800 Deutsche Marks, equivalent to about $48,000 USD back then—or more than $100,000 in today’s money.

The E30 M3 was a total flop in North America. It languished on dealer lots far too long. Most buyers just didn’t want an expensive, buzzy homologation special (and they still didn’t by the time the next M3 came around) that was something like 50 percent more expensive than a 325is but with 33 percent fewer cylinders.

On the road in the E30 M3

As always seems to be the case, it’s a holiday in Bavaria, which sadly means the planned route to the shores of Lake Walchensee and Kochelsee (nicer than it sounds) will be clogged with vacationers in caravans. Instead, we’ll go to the pastoral rolling countryside north of Munich where BMW tests its cars. A pair of camouflaged Z4 prototypes are running around, as is an SUV that look like a new X5.

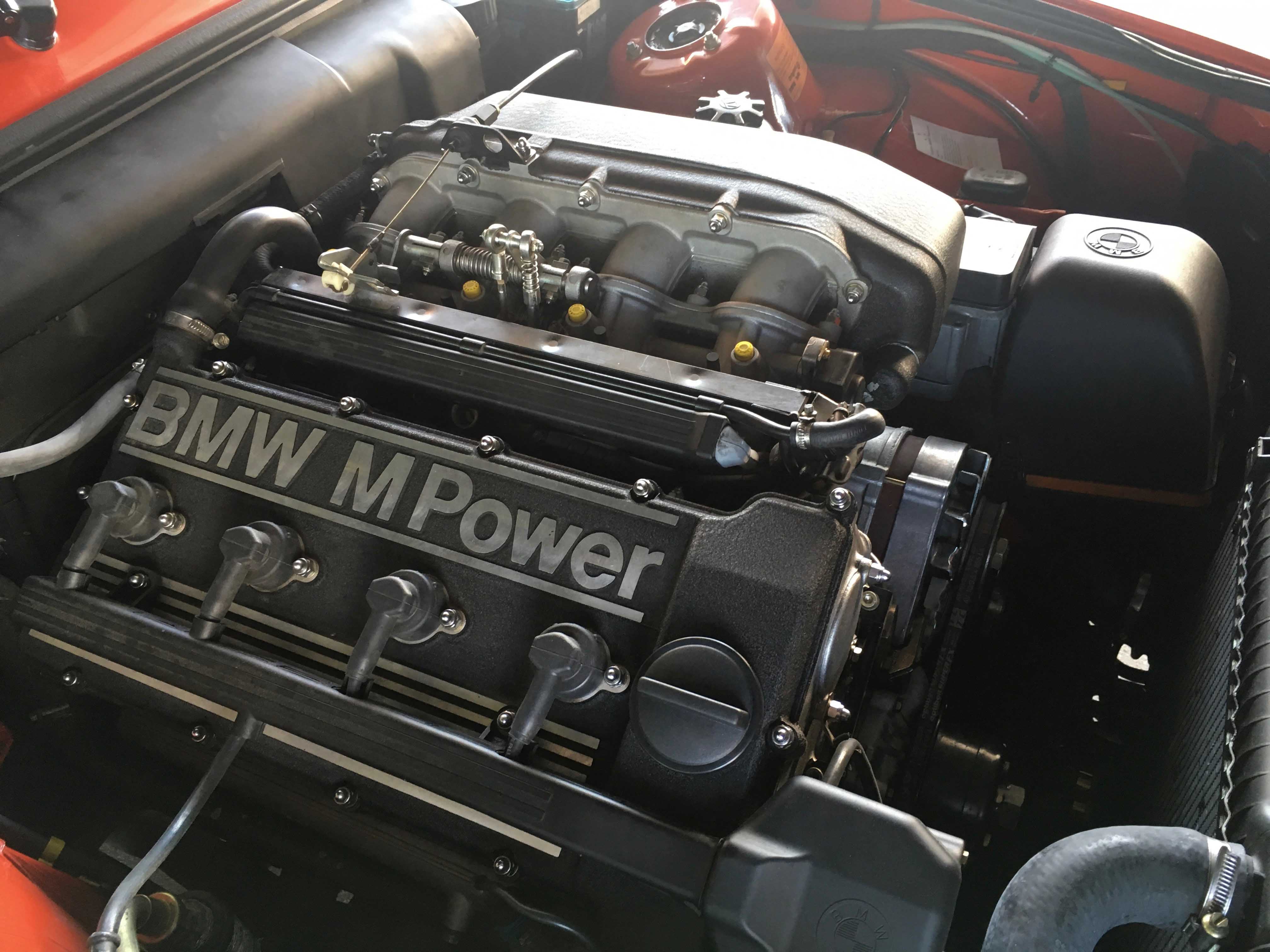

The M3’s 2.3-liter motor wheezes and chugs a few times before settling into a lower-pitched hum than your average four-cylinder. Individual throttle bodies and a simple mechanical cable linkage give it a tactile, grainy, instant response.

BMW engine-whisperer Paul Rosche designed the motor for racing, and for revs rather than low-end torque. Despite that, the S14 isn’t as peaky as others have reported. Those expecting to be thrown back in their seats will be disappointed, sure, but keep the motor above 3700 rpm and it delivers useful, instant, flexible power. Because the full 192 horsepower doesn’t arrive until 6750 rpm, you have a pretty large band to work with.

It makes a lot of noise—a breathy, hollow growl, occasionally pleasant—which is good for deluding yourself into thinking you’re accelerating quickly. But you’re not. You can drive it like a madman intent on exploding the motor, and the car takes it in stride. The temperature gauge stays rock steady. Only in traffic does it ever start to heat up.

Press the clutch to the bulkhead and it vibrates like a jackhammer. First gear on the dogleg gearbox can be difficult to engage. You can’t rush the long-throw lever. But the gears are spaced so that, when you’re driving flat out, each one slots into the next at just the right rpm.

There’s a small initial dead zone to the steering, but beyond that it’s noticeably quicker and heavier than on a regular four-cylinder E30. By modern sports car standards of course, the rack is slow, but it doesn’t matter. (Why do OEMs keep making quicker-ratio racks?)

Turn in a fraction of a second earlier than you’re used to. The car rolls quickly to the outside front wheel, and then just grips. You can really feel the lower, wider front stance of the M car as it digs into the road. The steering is surprisingly solid and meaty mid-bend, given how delicate and light the rest of the car is. It can feel wooden, until you start to play with the throttle. Every twitch of your big toe is relayed up through the steering, adjusting the car’s line with the kind of scientific precision Neil deGrasse Tyson would appreciate.

This is when the M3 is at its best, with the motor in the upper half of its rev range on a long sweeping bend that lets you enjoy the sublime balance of the chassis. In those moments, the M3 lives up to the hype. You can get a similar feeling from a new Porsche 911 GT3.

The tires are 205/55 R15 Continental Premium Contact 2s. They probably have at least 15 percent more grip than 1980s rubber, which is a shame. More oversteer on corner exit would be welcome.

Because this M3 is from the ’80s, a time before automakers thought it was okay to make sports cars—even homologation specials—as uncomfortable as a lead mattress, this car will happily cruise backroads for days. The steering is constantly fidgeting, chasing camber, but it’s light and never intrusive. The windowsill is at perfect elbow-resting height. The ride over rough backroads (they exist even in Germany) isn’t any worse than on a modern 340i—better, maybe.

Fact vs. fiction

The E30 M3 wasn’t quite what I imagined, despite all the ink that’s been spilled over it. The chassis is more hardcore, and the motor less peaky than expected. It’s very different from my own E30-generation 318is—stiffer, lower, more planted, and precise, plus it doesn’t roll like a frigate. But I can’t shake the feeling it’s underpowered.

Every ad for a new M Division car has it in the midst of tire-smoking slow-mo drift. The maniacs who grew up on Top Gear and Chris Harris videos expect cars to do Epic Drifts around every corner, and BMW is doing its dandiest to make that a reality these days. In the latest M5, there is even a dedicated Drift Mode.

In stark contrast, the original M3 is not built to drift, at least not on dry roads with modern tires. As fine as the road car’s chassis is, you feel slightly cheated, like you’re only getting half of its true potential. It’s missing the race car’s 300-horsepower engine. Or maybe I too am becoming one of those drift-addled maniacs.

Worth it?

“With values at more than $85k, you’re getting into the territory of rarer, more interesting cars,” Newton says. “Looking at our online insurance quotes for E30 M3s, they sit at a four-year low after their peak in 2016. So interest is on the decline just because so many people have gotten priced out of these and they can’t really go much higher.

Is an E30 M3 deserving of the eye-popping sums one goes for these days? Nobody can answer that for you—it’s your money, after all. But the market has clearly determined that passion for these cars is more than just a fad.

“With that said, demand for high-quality examples seems high,” says Newton, “and it seems reasonable to expect that values will remain high even if the value growth has slowed down.”

Ultimately, it’s impossible to separate the E30 M3 from the myth and status which surrounds it. You either buy into all of it, accepting the good with the bad because of what this car means for BMW’s heritage, or you look elsewhere for buzzy, boxy 1980s thrills.