Media | Articles

Savior of Aston Martin: Reuniting with the 1992 Virage 6.3

“Holy s**t, if I hadn’t been here for work, I’d have paid good money to see this.”

This was the Aston Martin Virage 6.3, an amazing automobile that I helped test for the U.K.’s Fast Lane magazine back in 1992. My enthusiastic comment is buried among tire pressures and other testing numbers in the yellowing pages of my notebook from that hot summer’s day at the General Motors proving ground at Millbrook, in Bedfordshire, England. What I vividly recall is this big car bellowing its rage at the world on the mile straight. In acceleration tests, it sat down on its tail with smoke curling off its massive 18-inch Goodyear Eagles, headlamps pointing at the stratosphere as the tire and road speed slowly synchronized and the Virage slipped its anchor like a highly animated ocean liner.

A small audience of hardened road testers and Millbrook staff had gathered to watch Mark Hales, a professional racing driver and Fast Lane’s talented associate editor, grimly launch the big Aston off the line time and time again. In the moment, we might not have realized that the hastily conceived performance edition of the slow-selling Virage would eventually be credited with saving the company—but we darn well knew it was something special, which is why I put it on the cover of Fast Lane Issue 102 in September 1992.

Fast-forward 30 years and that same Virage 6.3 test car and I have been reunited outside the Aston Martin Works service department in Newport Pagnell, Buckinghamshire. Company historian Steve Waddingham has already warmed the drivetrain by the time I arrive. The 6.3 is in notably good condition, the only light traces of age being a few stone chips around the lower rear sills and a bit of waviness in the dash underneath the windshield. The paint and chrome gleam, and the interior is clean as a pin, with creaking leather just like new. Massive uncatalyzed exhausts lend their muscular offbeat thunder to the Works courtyard. Is the Virage—all 4500 pounds of it, wrapped in an aluminum body 15.6 feet long, atop hand-built OZ wheels—still as intimidating as it was to my much younger self? Oh yes, with its bored-and-stroked engine pushing out a claimed 465 horsepower and 460 lb-ft of torque, I should say so.

When you hear the name Aston Martin, you might think of James Bond’s DB5 or the more recent Vanquish and Vantage sports cars and DBX crossover that compete with models from Ferrari, Lamborghini, Bentley, and Porsche. Compared with those marques, which are supported by resource-rich automaker parents, Aston Martin is but a minnow among sharks. Although the company has produced many absolutely terrific sporting grand tourers over the past century, “The Aston” has been spectacularly poor at making money. Gordon Sutherland, who owned Aston Martin between 1933 and 1947, once told me that “while saving Aston Martin was a reoccurring chore for all its owners, making money was optional.” It was much the same for Sutherland’s successor, David Brown, whose initials were used to name the longtime series of Aston cars. Estimates vary, but the company has gone bust at least seven times in its 109-year history. Even today, with a 25 percent stake taken by Canadian billionaire Lawrence Stroll, who owns the Aston Martin Formula 1 team, the carmaker’s finances are far from wonderful.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

In 1992, Aston Martin’s finances were truly dire, the company still reeling from the lukewarm reception to its 1988 launch of the Virage. A replacement for the long-serving, William Towns–designed V8, the beefy coupe wasn’t the best-looking car in the world, but it would be unfair to place the blame entirely at the feet of its designers, John Heffernan and Ken Greenley. When I interviewed Heffernan a couple of years ago, he was unapologetic, explaining just what had happened to his handsome original design. Traditionally, Aston Martin didn’t employ the services of an in-house designer, and, as newcomers, Heffernan and Greenley faced resentment, tiny budgets, and outright opposition from some departments. Heffernan had come from Audi, where each car could spend as many as 6000 hours in a wind tunnel, whereas the Virage got one day in a tunnel at the University of Southampton. When the design was almost fixed, Aston’s engineering department sneaked into the CAD system and added 6 inches to the height of the rear to get the downforce they needed. Then the tilt-up headlamps the designers had specified were abandoned for cost reasons and replaced with Audi 200 units.

But the biggest problem wasn’t so much the appearance; it was that the 330-hp Virage wasn’t very fast. “It didn’t really perform,” said Heffernan. “Victor Gauntlett [Aston’s chairman] said to me, ‘You’ve done your job well, John, but I’m afraid we should’ve got more performance out of it.’”

“I remember driving a Virage when I was at HWM [a longtime Aston dealer and specialist near London],” says Paul Spires, the current boss of Aston Martin Works. “I got back and Richard Zethrin [an Aston engineer who eventually ran his own restoration shop] asked me what I thought. I said it doesn’t go, it doesn’t stop, and it doesn’t go around corners. We need to do something about this.”

He wasn’t alone. Richard Stewart Williams—an independent Aston Martin specialist—and Works Service at Newport Pagnell were collaborating to improve the soft, slow, and spongy Virage. “Everybody was working together,” says Spires, “to keep the lights on at Aston Martin.” Time was of the essence, Waddingham reminded me, as Aston barely had any customers: In 1988, it produced 193 cars; in 1989, 208 cars; in 1990, 201 cars; in 1991, 168 cars; and, in 1992, only—wait for it—46 cars. The company wasn’t just on the ropes, its trainer was reaching for the towel.

A team under David Eales, who is now owner of performance specialists Oselli, started to address the Virage’s issues in handling, looks, and power. This was a true skunkworks special, with work proceeding long into the evening and weekends. Aston chairman Gauntlett wasn’t a huge fan of the effort to develop a factory tuning kit, but incoming chief Walter Hayes was. Ford had purchased 75 percent of Aston Martin in 1987, with the intention that Gauntlett would stay in the top job for another couple of years (he stepped down in 1991). By this time, Virages were being heavily discounted, but even that couldn’t make up for the way they lost value. At the time of the Fast Lane test, the list price of a Virage was £131,500, but you could pick up really good secondhand examples for less than £60,000. Which meant that a savvy performance-car enthusiast could have their used Virage rebuilt into a wide-bodied 6.3-liter, with all the handling upgrades, for less than the price of a new Virage.

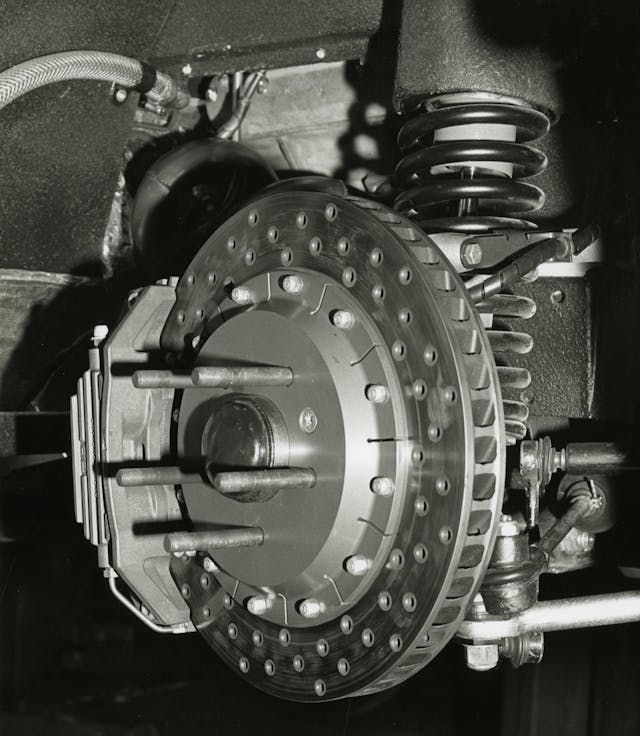

The total cost of the tuning package was about £60,000, for which Works Service would increase the engine’s output by about 40 percent; fit a new six-speed ZF transmission from the Chevrolet Corvette ZR-1; stiffen and modify the suspension; fit much larger brakes, with 10-inch front rotors and AP Group C racing calipers—the largest ever fitted to any road car—and bigger OZ wheels and tires; and sheath those bigger boots in handcrafted custom wheel arches. Inflatable cushions were added to the winged seats, and the factory would happily repaint the car in just about any color chosen by customers.

The twin-cam V-8 was bored to accept oversize Cosworth pistons, which connected to the long-stroke steel crankshaft with Carrillo rods. The cylinder heads were reworked by Tickford, an old Aston Martin in-house tuning arm, with Callaway-developed camshafts for the four-valve heads. Weber remapped the ignition and engine management, and the resulting engine revved smoothly to its 6500-rpm redline. Peak power was developed at 5750 rpm and 400 lb-ft of torque was available from 2200 rpm, with the 460-lb-ft peak occurring at 4250 rpm.

“Quite how all this fits with the factory’s engineering department appears to be a slightly touchy subject,” noted Fast Lane’s Hales at the time, although he also wrote that “what you get for the money is visually stunning.”

The performance hike was also stunning. We couldn’t max the car on the bowl at Millbrook, but the 174-mph claimed top speed was in sharp contrast to the 155-mph of the standard Virage. That’s not all. With the standard car’s figures in parentheses: 0–60 mph was reduced to 5.3 seconds (6.5 seconds); 0–100 mph took 12.7 seconds (15.8 seconds); and 50–70 mph in fourth gear was 4.3 seconds (5.9 seconds). This was the demonstrator prototype, and it wasn’t the easiest car to wring performance figures from. The soft drivetrain mountings twisted under the torque onslaught, and when tester Hale changed from first to second gear, the reverse torque pushed the gear lever gate around so he needed some dexterity to performance-test it—which, fortunately, he had in abundance.

It’s poignant to take the wheel after so long. The remarkable overstuffed seats, best described as racing armchairs, still support and cosset in equal measure. The wooden Nardi wheel is slightly too far away for comfort, with only a small rake adjustment, and the pedal box is too small for big feet in shoes with a welt. Vauxhall switchgear abounds, although the instrument binnacle with seven instruments behind a Perspex screen appears quite modern. Period pieces include a car telephone on a curly cord in the center console and a trip computer that looks like something James Bond would be sent off to recover from Smersh back in the ’60s.

One big change on this surviving test car is the replacement of the six-speed ZF gearbox with a five-speed Getrag unit with a dogleg first gear. No one seems to know when or why this happened, but the engine looks and feels like the same unit that rent the air at Millbrook all those years ago. This is one of the first Astons with a conventional handbrake release, which, along with unfamiliar gear positions and gate springing, makes starting off a bit embarrassing. Mind you, Newport Pagnell residents have seen a few supercars staggering out into the High Street in their time, so they take it all in stride.

As soon as you are underway, you don’t need to bother with first gear, so the gear change is effectively an H-pattern four-speed. You should be able to trickle through town in third at idle speeds, but this street-racer engine, with its fairly wild cam profiles, has some shunt at low speed, so it’s best left in second gear.

Out on the Northampton road, though, the old car sniffs the air like a war horse, and the engine has a warbling, woofling voice. You barely need more than a couple of the five gears, though the V-8 is really only pouring on the power from about 2500 rpm. This is a car built by enthusiasts for enthusiasts, and the way it reacts to the road that undulates north from where it was built is old-fashioned but quite up to modern standards. The big Goodyears ride through bumps fairly well, although mid-corner potholes cause a hop, a skip, and a thump. What feels quite ponderous at first is, in fact, a strong and tight car with terrific steering, the Adwest system still one of the finest ever fitted to a road car.

You can push the 6.3 through turns until the rear tires start to slide on exit, and easing the throttle tightens the nose into the corner. The Koni dampers handle body roll better than they do the front-to-rear pitching, which of course is exacerbated if you use the enormous stopping potential of the AP brake calipers. I can see why the factory wouldn’t sell you the engine modifications without the suspension tune back in the day; a standard Virage chassis couldn’t handle all that power.

In deference to the car’s age, I didn’t try a standing start, but even if you floor the throttle from 20 mph, the Aston squats and its hood rises. In less than an hour, I drained the quarter-filled tank, though the touring range of about 325 miles on full tanks would not be unacceptable even if the price of filling the 25-gallon fuel tank would be.

Firm numbers are hard to find, says Aston historian Waddingham, but he reckons Works Service converted about 60 Virages in total—including the cars that just had the cosmetics done. “Between 1992 and 1993, I was forever picking kits for the 6.3 conversions,” he recalls from his time working in the parts department. Spires also notes that few standard-body Virages were sold after the 6.3 conversion became widely known. So the modified Virage kept the lights on and got Aston through a tough spot until Ford took full ownership and lavished resources on the brand as part of its Premier Automotive Group.

Thirty years on and with the benefit of hindsight, I’d not change a thing in the 6.3.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.