Media | Articles

Night at the Museum: Nashville’s Lane is a bright light in dark year

Night at the Museum is a new series from Hagerty—visiting car museums around the country, telling stories from the silence. In a year where public spaces offer unique resonance, we decided to visit our favorite automotive temples at night, when they’re empty and quiet. We brought with us a heap of curiosity and the keys to every door in the building, wheeled or otherwise. Enjoy. –The Editors

There are microcars and three-wheelers, false starts and aborted projects. A rare MG Metro 6R4 homologation special lives in the basement, one story beneath a Citroën Group B rally project and a small cluster of propeller-powered cars. The amphibious military transporter stationed outside is literally big enough to crush a house. One of the airplanes hanging from the ceiling is a series-production machine made from an extension ladder.

“That went fine,” David Yando says, laughing, “until the company making the ladders got ahold of the dude and was like, ‘Stop making airplanes from our ladders! That’s not what ladders are for!’”

Yando manages Nashville’s nonprofit Lane Motor Museum. His story and chuckle are the Lane in a nutshell: as much love for the ladder-plane in the rafters as for anything else in the building. Which is why I wanted to spend the night there, partly to bask in the assembled rarity, but also to enjoy the history and silence as a sort of refresh for the soul. A night at the museum is a quaint romantic notion, the children’s book that spawned a $1.3 billion Hollywood franchise notwithstanding. Thus, with the kind permission of museum staff, a photographer and I were allowed to wander the place unrestricted into the wee hours, up close and personal with each car, no door in the building unlocked.

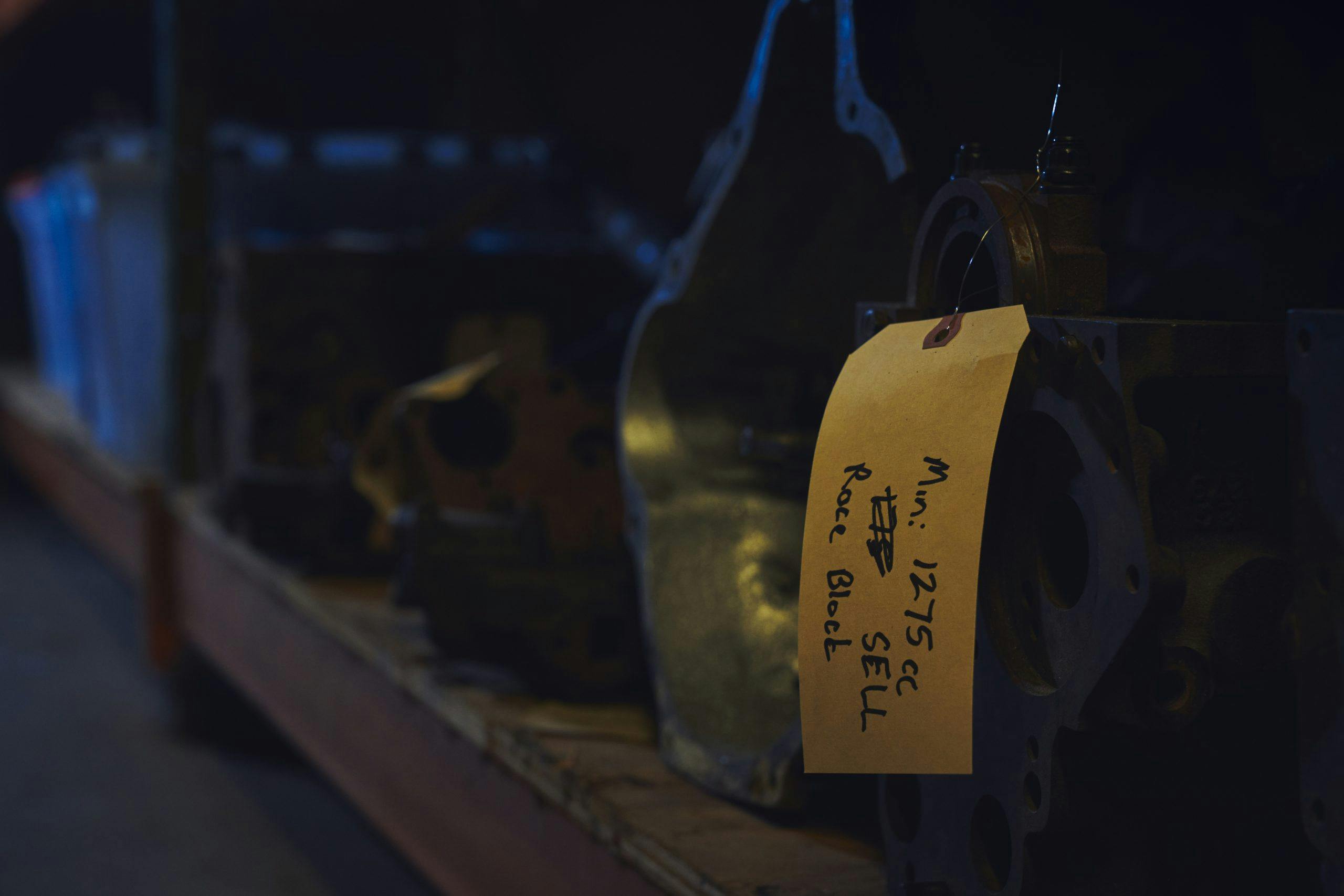

The museum itself was born almost 20 years ago from the personal collection of local entrepreneur Jeff Lane; its claim to fame is equal parts eclecticism and practical vibrance. Each of the institution’s more than 300 vehicles runs and drives or is on the way there, because Lane him-self believes cars were not built to be still. This philosophy applies to the museum’s Pebble Beach–winning, gyroscopically stabilized 1967 Gyro-X two-wheeler, but also to its multiple amphibians and propeller beasts. The core of the place is a small restoration and service shop running five days a week solely to keep the collection alive.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The modern automobile did not spring fully formed from humanity’s hip. We had to work to get it right, and nowhere celebrates that process—all the false starts, dreams, and experiments—like Tennessee’s weirdest automotive mecca. The machines showcased on these pages were chosen to illuminate the Lane’s philosophy, and to shine a light on stories near and dear to its heart. More to the point, although each of these cars was something of a technological cul-de-sac, the optimism they embody serves as poignant reminder that, in even the roughest of times, we move forward only through knowledge of our mistakes and wrong turns. Or as James Baldwin put it: “If you know whence you came, there is really no limit to where you can go.”

The Supercar That Wasn’t

2014 Volkswagen XL1

I found the VW first, drawn by its shape. A near-featureless teardrop in a room full of lumpy industrial art.

When you get down to it, Porsche’s first overall Le Mans win in 1970, as well as the 2005 Bugatti Veyron, sprang from the mind of one man. That same man also gave the world a two-seat, limited-production, one-cylinder, carbon-bodied, 1800-pound, plug-in diesel hybrid designed to average 100 miles on a liter of fuel.

Few people have bent the arc of the automobile as much as the late Ferdinand Piëch. A grandson of Ferdinand Porsche, Piëch worked in Porsche-Audi-VW corporate as early as the 1960s. He played a hand in the development of both the Porsche 917 and the Audi Quattro, but his greatest impact came years later, and on an even grander scale. From 1993 to 2015, Piëch played a commanding role in Volkswagen management, driving his engineers to birth moonshots big and small. The company purchased Lamborghini and Bentley. It also brought Bugatti back from the dead, Piëch’s orders for the marque demanding a modern, safe, and EPA-compliant road car capable of at least 1 mph more than the 917 generated at Le Mans. The imposing 1001-hp Veyron resulted.

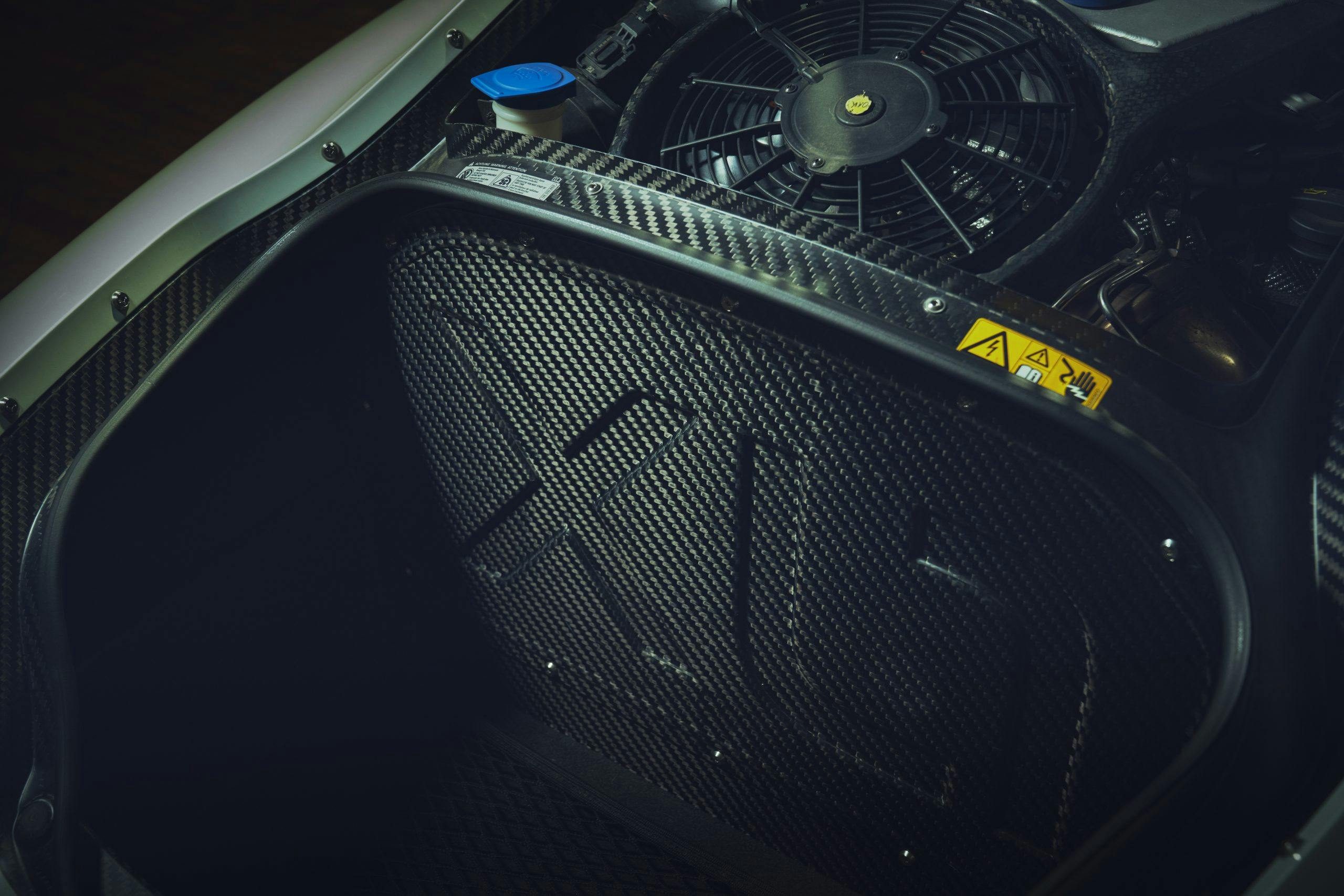

Less often remembered from this period is the tiny Volkswagen XL1. The 240-mpg XL1 was the yin to the yang of the 250-mph 16-cylinder Veyron. The VW is both more rare than the Bugatti and an equal landmark of engineering. When new, the XL1 cost around $146,000. For that price, you got a car in which fuel economy was the sole end and the electronically limited top speed a mere 100 mph. Steel and iron comprised less than a quarter of this peanut’s curb weight; aluminum and carbon were its primary ingredients. The VW’s tiny, bullet-wedge body gave so little wind and rolling resistance that its shape required just 8 horsepower to maintain 62 mph on a windless road. To help further reduce drag, the engine was cooled by high-pressure air collected from the rear diffuser and exhausted atop the body. Some testers saw more than 300 mpg without hypermiling. For a brief moment, the XL1 was the most fuel-efficient new vehicle on earth, but the 250 made were never sold in America.

The car is a squat little thing, as nicely finished as any modern Volkswagen. Only the scale hints at the work to build it. The tops of the tiny doors are no more than waist-high. The shift lever is borrowed from a Volkswagen Golf. The cabin is cozy but almost too intimate, like an air-cooled Beetle or an early 911. From the driver’s seat, stretched arms can touch both doors at once. The A-pillars are so reclined as to seem aimed at your nose. The window lifts are hand-crank, not electric—an anachronistic choice even a decade ago, but also a pointed engineering decision, to save weight, and one of thousands of single-minded steps toward a remarkable goal.

There is undeniable purpose here, to say nothing of a sense of origin. Some cars sing loudest in their intended environment; outside that world, they never quite feel at home. Behind the wheel, I tried and failed to look out the windshield without imagining autobahns or the stark cleanliness of German gas stations. Or the seemingly baked-in ability of German culture to relentlessly abandon the past and start over.

This is what happens when a massive international corporation soaking in money decides to nudge the edge of an envelope. In a dark room full of interesting vehicles, I couldn’t help but linger, marveling at what they achieved.

The Kart With a Roof

1964 Peel P50 Replica

There is no reverse gear—just a handle, a chrome piece of what looks like cabinet hardware screwed to the body beneath the rear window. To reverse, you are supposed to lift the rear wheels off the ground with one arm, turn the 250-pound Peel P50 around, then simply hop in and drive off in the opposite direction like a civilized person. After all, when your car is 4.5 feet long, why wouldn’t you pick it up?

Peel Engineering entered the car business in 1955. Amazingly, the 1962–65 P50 was not the company’s first production device. Nor its first car. Nor even its worst idea. The firm, based on the Isle of Man, began life making fiberglass molds for motorcycle fairings and boat hulls. It once built a prototype hovercraft powered by a 500cc parallel-twin from a Triumph motorcycle. It also constructed a bizarre little three-wheeled microcar, the Manxman, of which no known examples remain.

The Manx are a lovely people. Also completely mad.

Around 50 examples of the P50 were built. The car cost just under £200 when new and powered its third (and only rear) wheel with a 49cc scooter engine. In 2016, a restored P50 inexplicably sold at auction for $176,000. A Peel is not so much car as a suggestion of car, a joke about car, a story of car you once told a long time ago, to a person who had never seen an automobile of any sort, and that person was like, Well, that sounds nice, and then they tried to draw the thing for their kid sister while halfway into a bottle of wine, and the P50 is what came out.

I grabbed that reverse handle and carried the Peel around for a bit. My shoulder grew sore in the first 3 feet. Even lifted as such, the car’s roof still sat below my nipples. A P50’s interior smells of lawn mower, all fossil fuel and garden-shed funk, partly because the engine sits uncovered beneath the driver’s elbow. Starting it means flipping a motorcycle-style kickstart lever forward with your right hand, knuckles squeaking past the wheel. You are kept company by tie rods the thick-ness of pencils—they hang out near the pedals—and the sort of spatter-paint finish common to bowling alleys and bass boats. Hospital gurneys suggest more stability at speed. The knees-up driving position, for its part, suggests violent death, constipation, and low-brimmed hats, in that order.

“Jeff says you shouldn’t touch the brakes while turning,” Yando said, “because that almost guarantees a rollover.”

The Manx were disappointed; the P50 was intended to become something like the next Austin Mini. It did not. The model remained a little-known historic footnote until Jeremy Clarkson drove one through the London BBC offices for a 2007 episode of Top Gear. The moment was played for laughs, but it served also as stark reminder that the age of the microcar—staggering risk and genius packaging coupled with extreme practicality—now sits more than half a century in our past. It is funny partly because we cannot imagine going back there; who on earth would call this little monkeymobile a car, instead of a death trap, or a shoe, or a particularly evolved coffee pot? But what a happy little moment it was. A time when we were briefly convinced that simpler was always smarter, and to hell with the consequences.

You could ask what happened, why we no longer believe in redemption through reduction. But everyone knows the answer. A modern Mini Cooper would swallow a P50 whole, and all you’d have to do is fold the seats.

The Czech Proto-Beetle

1938 Tatra T97

If you squint, a Tatra T97 looks like a Beetle. The Volkswagen of Hitler and Porsche, designed to put a country on wheels. This is convenient, as Hitler killed the T97 to help the Beetle survive, and Ferdinand Porsche could have called the Tatra family.

Tatras are Czechoslovakian. The marque is the third-oldest carmaker in the world, behind only Daimler-Benz and Peugeot. Tatra’s parent company, Nesseldorfer Wagenbau, began life in the late 19th century as a manufacturer of horse buggies and rail cars. Decades later, the firm allowed an engineer named Hans Ledwinka to experiment and flourish. Between the wars, Ledwinka dabbled in cutting-edge concepts like streamlining. He worked with Porsche, who either collaborated on his ideas or pirated them for the Beetle, depending on whose account you believe. (“Sometimes I looked over his shoulder,” Porsche once said, of Ledwinka, “and sometimes he looked over mine.”)

The most well-known Tatra, the T87, was a suicide-door teardrop sedan with a fin on the back and an air-cooled, largely magnesium V-8 mounted behind the rear axle. The car’s handling was such that the German army supposedly forbade officers from driving captured examples during World War II. Too many deaths at the wheel, if you believe the lore. (See The Death Eaters, Chapter 1 for more.)

The T97 resembles the T87, though the 97 is smaller and generally simpler in detail and finish. An air-cooled flat-four lives behind the rear axle. Erich Ledwinka, Hans’s son, designed the 97 to do the job of the Hitler-backed Beetle—affordable everyman transport, comfortable and efficient—but the T97 predates the Volkswagen by years. The engineering similarities prompted Tatra to sue; the lawsuit was paused when Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia and forcibly idled Tatra’s plant. The Beetle went on to become the German People’s Car and help build one of the largest carmakers the world has ever known, and the 97 faded into history.

All of which means you can’t meet a T97 without thinking about alternate timelines. The interior is velour-lined and comfortable, simpler than a Beetle’s without feeling plain. Mostly, however, the car feels like a Beetle where the engineers spent more time thinking about people. There is far more space here, the windshield more distant and the rear seat an atrium. Atrocious rear visibility is the only downside, the rear of the car a tunnel, all tiny window and fat pillar. The engine is larger and looks harder to service, its components a little more buried.

History can sometimes carry strange weight. I spent most of my time circling the Tatra, drinking in the lines and odd little details. It was artful where a Beetle wasn’t, more quirky. The “face” of bumper and headlight was far less cheerful.

Volkswagen settled with Tatra after World War II, paying some 3 million deutsche marks to the heirs of the brand’s former owner on grounds of patent infringement. Ledwinka senior was imprisoned by Communist Czechoslovakia for six years, until 1951, under false accusations of collaborating with the Nazis. He died, still bitter, in 1967. Erich Ledwinka designed the revolutionary Haflinger off-road vehicle for Steyr-Puch, as well as the similar Pinzgauer.

None of these words are household names, but you can still walk into any kitchen in America and find someone who knows the Beetle. Proof, in the end, that we tend to remember only the heavy hitters, even if they weren’t first across the line.

Maximum Dynamism

1933 Dymaxion Replica

Jeff Lane wanted to know what a Dymaxion drove like, so he had one built. Just three Dymaxion cars were made originally, in 1933 and 1934, and the only surviving example now sits, stagnant, in a museum in Reno. So several years ago, a small team of craftsmen in the Czech Republic created, from scratch, a toolroom copy of a 1930s car originally designed to bring about the future.

Jeff Lane, ladies and gentlemen. Most people would have simply cracked a book.

In the early 1930s, an inventor and self-labeled “comprehensive anticipatory design scientist” named Buckminster Fuller decided to build a car. For help, he enlisted his friend William Starling Burgess, the naval architect behind three America’s Cup winners. Two of his boats were J-class models from Rhode Island’s legendary Herreshoff yard, and thus some of the largest and most graceful sailboats ever built. Burgess gave Fuller’s car a wooden body structure, aluminum skin, and no fewer than three separate steel frames, plus a midmounted, 221-cube Ford flathead V-8 driving the single rear wheel that also steered the car.

If all that engineering reach wasn’t enough, the car was envisioned as a detachable part of a large aircraft—basically the plane’s landing gear. Three examples were built, each different in detail. Lane’s replica most resembles the first Dymaxion but features mechanical updates from the later two that were meant to improve the layout’s nightmarish road behavior. Even so, the rear suspension is a hellscape of pivoting girders and dampers, famously awful at its job. The engine is virtually starved of cooling air. You enter the interior by climbing in and up, expecting to step down once inside but instead meeting a floor high enough that passengers sit with legs straight ahead. The headliner is curved wooden ribs and varnish.

As for the name, it was a Fuller hallmark, a portmanteau of the words dynamic, maximum, and tension. There is a joke in there, but your author is not rude enough to make it.

Adjusted for inflation, the first Dymaxion cost around $130,000 to build. Three months into its life, it crashed on a public road, killing the driver. The incident prompted Fuller’s next customer to cancel his order, so Fuller kept the second Dymaxion as a demonstrator. Then he rolled the car on the road in May 1935 with his wife and daughter inside. Funding dried up soon after.

Lane once drove his Dymaxion the 600 miles to Florida for the Amelia Island Concours. Others who have helmed the thing call it nerve-racking for just 600 feet.

I stayed with the Dymaxion for a long time, watching light play over its hulking curves. It’s tempting to view the thing as a depressing dead end, but the Lane is full of nothing if not dead ends, and the Dymaxion somehow feels like one of the cheeriest. If there’s a sadness here, it’s only that we have largely walked away from viewing our next steps as Fuller did—that 1930s vision of a more optimistic and resolved future, all heady dream and Popular Science.