Media | Articles

Meet the all-out French automaker that died defying WWII

Talbot-Lago. No doubt you’ve heard the name called out in the dulcet tones of a concours emcee as beautiful people flit among beautiful cars while Camembert and sauvignon blanc are served. Talbot-Lago stands with Bugatti, Delage, Delahaye, and Voisin as one of the great practitioners of French bespoke carmaking from the great interwar years of flourishing art deco design. From a tiny factory in the Paris suburbs that never had more than 450 workers, Talbot-Lagos roared forth to race at Le Mans, they battled fang and talon with the ascendant Germans on the Grand Prix circuit, they drew crowds of gawkers at the annual Paris Salon de l’Automobile, and they were the preferred bolides of an exclusive coterie of moneyed elite who fled to the Riviera in autumn.

Mike Regalia’s 1949 Talbot-Lago Grand Sport came after all that. After a cataclysmic war smashed the old order and impoverished a continent, as Paris’s thriving carrosserie industry was being reduced to vapors, and as the hard-drinking, hard-smoking boss, Tony Lago—who had once escaped a Fascist hit squad by lobbing a grenade into a cafe—was conniving to keep his factory open through sheer force of will. None of which detracts from the fact that Regalia’s Grand Sport, one of only around 31 to 35 cars thought to have been built between 1948 and 1951, is a spectacular automobile, even as it sits idling on a California side street in largely unrestored condition.

“It’s kind of like owning a Bugatti,” says Regalia, who started in 1978 as an in-house painter for the great car collector and cosmetics baron J.B. Nethercutt and retired in 2005 as the Nethercutt Collection’s president. “It’s very rare air. These are one-off custom coachbuilt cars, and they were some of the last.”

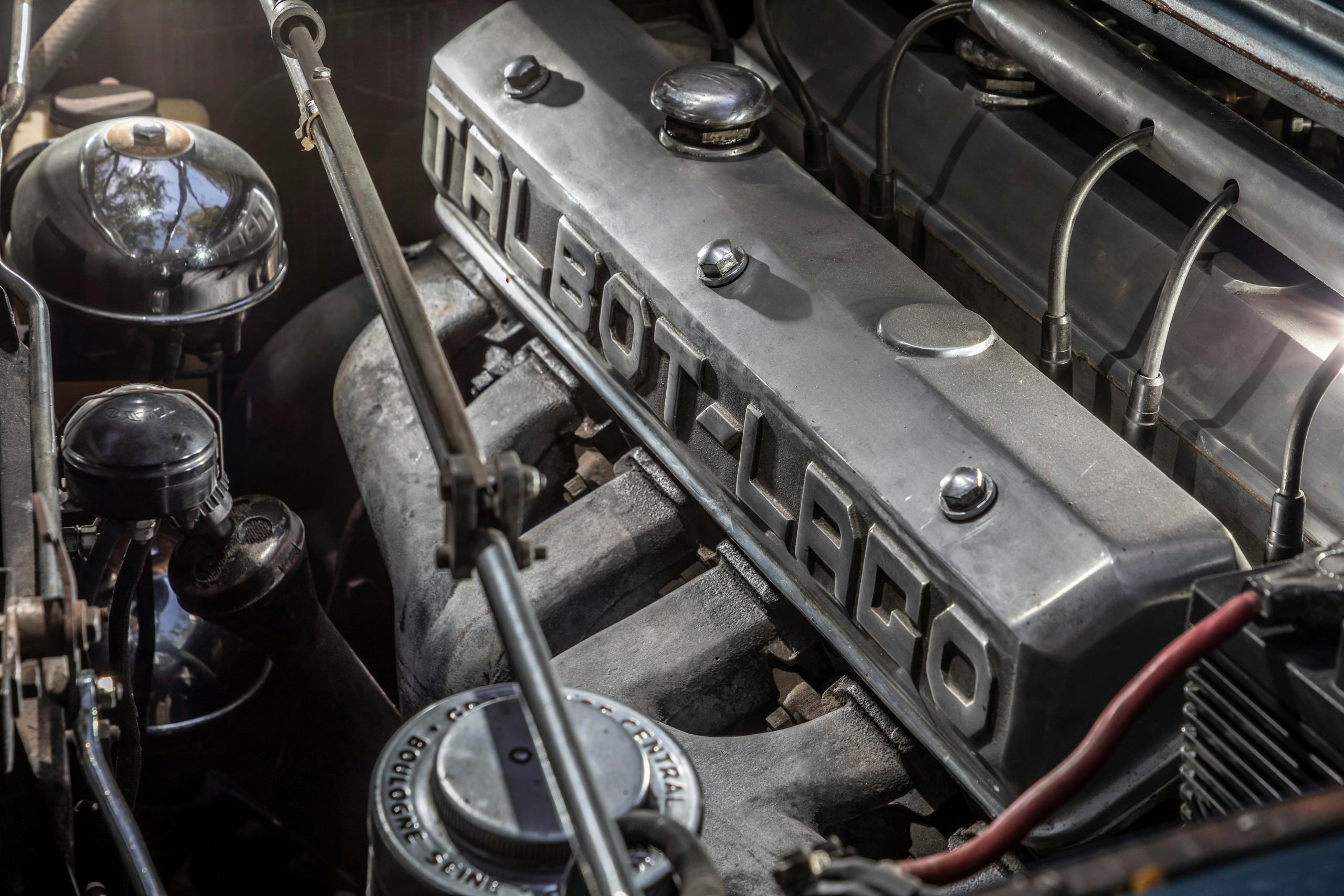

We ensconced ourselves in the Grand Sport’s ridiculously cramped cockpit for some action shots for the photographer. The T26 Grand Sport has about the same space inside as a 1958 Corvette or, more contemporaneously, a Jaguar XK 120. People were obviously smaller back then, or just more forgiving. The 4.5-liter pushrod straight-six sucks through its triple carburetors with a raspy snarl while its exhaust pushes the gases out with an arresting burble. Regalia, sitting in the right seat per prewar French convention, snicked the column shifter for the Wilson preselector gearbox down a notch, from point mort, or neutral, into first, and we rolled off.

Talbot-Lago is one of those names with complex parentage, somehow surviving the incestuous turmoil of the early auto industry when most new automaking start-ups lived lives of brief, unprofitable anguish before dying or merging with others. For those interested in the particulars, the history is cataloged in minute detail in Peter Larsen’s two-volume compendium, Talbot-Lago Grand Sport, a towering work of research that is also pleasantly readable. “One Sunday in 2008,” Larsen explained via email in the same breezy manner that he wrote the book, “I was reading yet another T26 Grand Sport article that contained a baker’s dozen of mistakes—an article that perpetuated the same mistakes others had made before moronically repeating them. I got fed up and decided to rectify matters. It took four years.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

See what we mean about the writing? Much of the following information has been taken from Larsen and his co-writer Ben Erickson, who are by their own admission indebted to the research of others on this obscure topic. In brief, the company’s tale started with bicycle-maker Pierre Alexandre Darracq, who built what was to become the Talbot-Lago factory in 1896 in the Paris suburb of Suresnes, about 5 miles west of the newly erected Eiffel Tower.

Around that time, a French former bicycle racer and bicycle maker named Adolphe Clément took a trip to London, where he learned of the newly invented Dunlop pneumatic tire. He bought the French rights, which made him a fairly instant millionaire. Keen to move into automobiles, Clément partnered with the British lord Charles Chetwynd-Talbot, the 20th Earl of Shrewsbury, to buy Darracq’s bicycle business while also founding Clément-Talbot Limited in England to build cars.

Lots of drama and disasters ensued over the next 30 years as companies collapsed or merged, a succession of mediocrities took charge, plans were laid and schemes were schemed, and vast fortunes were burned. Perhaps sensing his end was near, Lord Talbot exited the car business in 1919 and died two years later, not living to see how his family name would be pasted on all manner of vehicles from both sides of the English Channel until well into the 1980s (the current heir, Charles Henry John Benedict Crofton Chetwynd Chetwynd-Talbot, the 22nd Earl of Shrewsbury, no doubt takes some satisfaction from it). Today, the name Talbot is variously pronounced as Tal-beau or Tall-bit depending on whether you side with the French or English.

In 1933, as the surviving car company, Automobiles Talbot, was hemorrhaging cash at a particularly robust rate and its British shareholders were bemoaning their collective plight, along came Talbot-Lago’s most illustrious personality, Antonio Franco Lago, or “Tony” to his friends, lovers, and numerous creditors. Lago was born in 1893 to a middle-class Venetian family and attended technical college while falling into the orbit of a young Benito Mussolini. Lago is thus otherwise semi-notorious as one of the 50 founding members of the Italian Fascist Party. However, as Larsen writes, he was more interested in lofty ideals than jackbooted thuggery and, after serving as an aircraft mechanic during World War I, turned on the party. Which is why they eventually sent a gang of black-shirted assassins to take him out. After tossing the grenade to escape, Lago fled to Paris, then onward to London, and never returned to his homeland.

In London in the 1920s, while running a small shop specializing in Isotta Fraschini cars, Lago became enamored with the newly invented Wilson preselector gearbox, a type of semiautomatic manual that offered benefits in noise and efficiency over contemporary non-synchro manuals while also reducing shifting to a gentle flick of the wrist. Lago wrangled the rights to assemble Wilsons in France—though Larsen is not convinced that Lago ever actually paid for it—and started building his empire.

In 1933, he approached Talbot’s grieving shareholders with a highly dubious plan to take over and run the factory in Suresnes. Talbot-Lago was effectively born, and right up until the Nazis let themselves into Poland in 1939, the company produced a few hundred examples each year of a dizzying—and mostly unprofitable—array of road and racing cars. From the ordinary Minor 13CV (in France, most cars were denoted by their cheval-vapeur, or taxable horsepower) to the fabulous T150 sports cars that would be bodied by the best coachwork designers in France, including the uninhibited Joseph Figoni and the Russian Jewish émigré Iakov “Jacques” Saoutchik.

The idea for Regalia’s azure blue roadster was born in the latter days of the war, when Tony Lago joined with his Paris colleagues in the coachbuilding business to try to pretend that the war never happened. Talbot-Lago would ride back to glory partly atop the T26 Grand Sport, a compact and lightweight two-seater built with only few changes on the bones of the company’s old prewar Grand Prix cars. Even as the bullets still flew, Lago and his chief engineer, Carlo Marchetti, worked on a new version of the company’s 4.5-liter, 26-cheval-vapeur inline-six, with twin cams in a long-stroke block topped by semi-hemispherical combustion chambers.

However, postwar austerity, shortages, and inflation kneecapped French car production, Lago spending much of his days haggling with local officials for allocations of raw materials. By the time the Grand Sport debuted in 1948, the best from England, Germany, and Italy was already better, and the car was obsolete the day it arrived. “I don’t think numbers sold [fewer than 35] is a measure of success—that is a sort of McDonald’s X-billion sold philosophy,” said Larsen, who is curating a special Grand Sport class at the 2022 Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance. “The car was an extreme sales flop, in the sense that it was the wrong car at the wrong time, and at a hideously expensive price. But I think that is beside the point; it was an outrageously exclusive and beautiful individually coachbuilt objet d’art on a gorgeous, if outdated, chassis.”

At 2.65 meters, or 104.3 inches, the Grand Sport’s wheelbase was 2 inches longer than the aforementioned ’58 Corvette’s, but Talbot-Lago’s lengthy T26 inline-six consumed much more real estate than the legendarily compact small-block. The GM mention is not by accident; Saoutchik supplied the body for the debut Grand Sport, an extravagant coupe in pastel green with brown accents that stole the 1948 Paris Salon de l’Automobile. It also heavily ripped off the 1942–49 Buick fastbacks designed under Harley Earl at General Motors. Saoutchik would do several more Grand Sport coupes using variations on the Buick theme.

Regalia’s Grand Sport was the factory’s 17th chassis, delivered to its buyer, a Mr. Paul Gerbe of Paris, on September 29, 1949, exactly one month after the Soviets detonated their first atomic bomb. Compared to the rakish Saoutchik coupe that preceded it and the fenderless racer that came after, Regalia’s Dubos-bodied convertible is a study in conventional elegance, vaguely resembling a contemporary pontoon-fender Triumph 1800 roadster, albeit with far more graceful lines. The three Dubos brothers had taken over their father Louis’s Paris coachworks upon his death in 1946 and attempted to continue building commissioned one-offs in the firm’s tastefully understated style, but by the mid-1950s, that business was dead and the company switched entirely to building buses and commercial vehicles.

Regalia’s car survives as the only unrestored Dubos Grand Sport of the four to which Dubos supplied coachwork. The bare chassis alone cost Gerbe roughly the equivalent of $5800 at a time when a new Cadillac Series 62 convertible ran about $3500—and this in post-occupation France, when people were still lining up for bread. It took Talbot-Lago five months to build the chassis using tools and equipment that mostly dated back to 1912. Thus, you can see why bespoke carmaking was rapidly nearing its end, and Talbot-Lago died with its chief motive force, Tony Lago, in 1960, having outlived its era and most of its contemporaries by at least a decade.

Eventually this Grand Sport made its way to America and received a fresh paint job that is, by Regalia’s estimation, slightly darker than the original color. It should be said that Regalia is a paint-matching expert who helped the Nethercutts win six Pebble Beach Concours Best of Show awards, along the way acquiring, restoring, and reselling Steve McQueen’s Ferrari 250 GT Lusso. He bought the Grand Sport out of a San Diego–area collection in 2019, figuring it might be his only opportunity to own an example of French bespoke coachwork at a somewhat-affordable price.

“Postwar coachbuilt cars are actually rarer than prewar,” he says while manhandling the Grand Sport on a twisty road in summertime heat, “because World War II destroyed the industry. And this one was an open car, and unrestored, making it even rarer among the rare. Three-quarters of the Grand Sports were closed.” Postwar Talbot-Lagos, except for the million-dollar Grand Sports, are relatively affordable, partly because of obscurity, partly because of high restoration costs, and partly because at concours they tend to be lumped into postwar sporting classes with much more popular Ferraris and Gullwings.

By the looks of it, the Talbot-Lago is no easy thing to drive, but then it is more than 70 years old and based on technology from the 1930s. Author Peter Larsen, who calls himself a “Talboiste” of many years, says the cars are nonetheless real sports cars by the definition of their day, especially the earlier Grand Sports whose wheelbases were almost 8 inches shorter than the later cars. “It is a direct successor to the prewar T150 C-SS and the chassis is virtually identical to the prewar GP cars, with a great old-school 4.5-liter six and that marvelous Wilson preselector,” says Larsen. “The faster a Grand Sport goes, the better it goes. This isn’t a Delahaye, just as a Duesenberg is not a Packard.”

Running hot from all the photography work in the California sun, Regalia’s car signaled that it was time to call it a day. He’s owned more usable cars, including a 1972 Ferrari Daytona that he bought decades ago and is currently restoring in his garage. But he’s utterly smitten by this obscure sliver of French artisanal carmaking and the story of its suave and wily chieftain, who deserves to be mentioned with Ettore Bugatti and Enzo Ferrari in the ranks of the industry’s driven visionaries.

Even as the company was dying, “a Talbot-Lago finished 1-2 at Le Mans in 1950,” Regalia notes. “This is basically the same chassis with a custom coachbuilt body on it. In the collector car world, that’s as good as it gets.”

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark us.

Great article.

A 1949 Talbot-Lago T-26C Grand Prix was, for a number of years, raced at the Pittsburgh Vintage Grand Prix in the 1980s through the 1990s. Watching the owner/driver-Henry Wessells of Paoli, PA power that car around the tight course lined by stone walls was magical.

Holy cats!!!!! I never thought I would see a car that makes an E type or a 246 Dino look like the consolation prize at the kissing booth. JESUS-SQUEEZUS that thing is beautiful. Beautiful images.

Beautiful car and color

Beautiful car!

Great story, gorgeous car, terrific craftsmanship. Thanks!