Media | Articles

King of the bulls, the Miura is the most collectible Lamborghini for good reason

The words “Lamborghini” and “supercar” tend to go hand in hand. A subsidiary of Audi for more than 20 years and counting, Lamborghini delivered nearly 7500 vehicles worldwide in 2020 and over 8200 in 2019. Go for a stroll in a nice part of L.A. or Miami, and chances are you’ll see a brightly painted Lambo streak by or hear one crack an upshift a few blocks away.

Turn back the clock to 1965, however, and Lamborghini was a much different company. With just a few years of automobile manufacturing under its belt, the Sant’Agata Bolognese–based tractor builder was focused on producing small batches of refined, mature gran turismos that aimed to best Ferrari’s equivalent road cars. Frivolities like track capability were not considered. The Miura started to change that approach, putting Lamborghini down the path that eventually brought us brash exotic cars, like the Diablo and Aventador, with bullfighting names on their tails. Even outside of Lamborghini, the Miura came to embody the “supercar” as we know it.

No wonder it’s the most valuable production Lamborghini of all. In particular, the Miura has appreciated drastically over the past 10 years even relative to other classic Italian thoroughbreds. Not all Miuras are created equal, however, and exactly why that is requires us to delve into a bit of history.

A Miura for the road, inspired by racing

Lamborghini’s first car, the 350 GT, began steady production in 1964. Several company engineers and designers started thinking about what they could do next, most notably Paolo Stanzani, Bob Wallace, and Gianpaolo Dallara.

At the time, everyone in the trio was in their mid-20s. Ferruccio Lamborghini was 48. The group was enthusiastic about racing, where mid-engine cars were dominant. The boss, however, was adamant about staying away from motorsports, in order to tailor cars to the street. Nevertheless, Mr. Lamborghini budged and gave the team the go-ahead to develop a mid-engine sports car. “Nobody at Sant’Agata thought it would amount to more than a handful,” Bob Wallace later remembered. Maybe it would cause a stir, or serve as good buzz for Lamborghini’s other models. Regardless, it would primarily be a street car, albeit built in the image of contemporary racing sports cars.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The chassis design was a monocoque with an integral roof, leaving the front and rear of the bodywork as unstressed, hinged panels, much like a Ford GT40. Lamborghini constructed the chassis from steel and drilled holes for lightness wherever possible. The first real challenge came in deciding where to place the engine, Lamborghini’s signature V-12, developed by Giotto Bizzarrini and then displacing 4.0 liters. It was long—significantly more so than the GT40’s V-8. Mounting the V-12 longitudinally, as in other mid-engine cars, would have meant lengthening the car’s wheelbase and compromising handling.

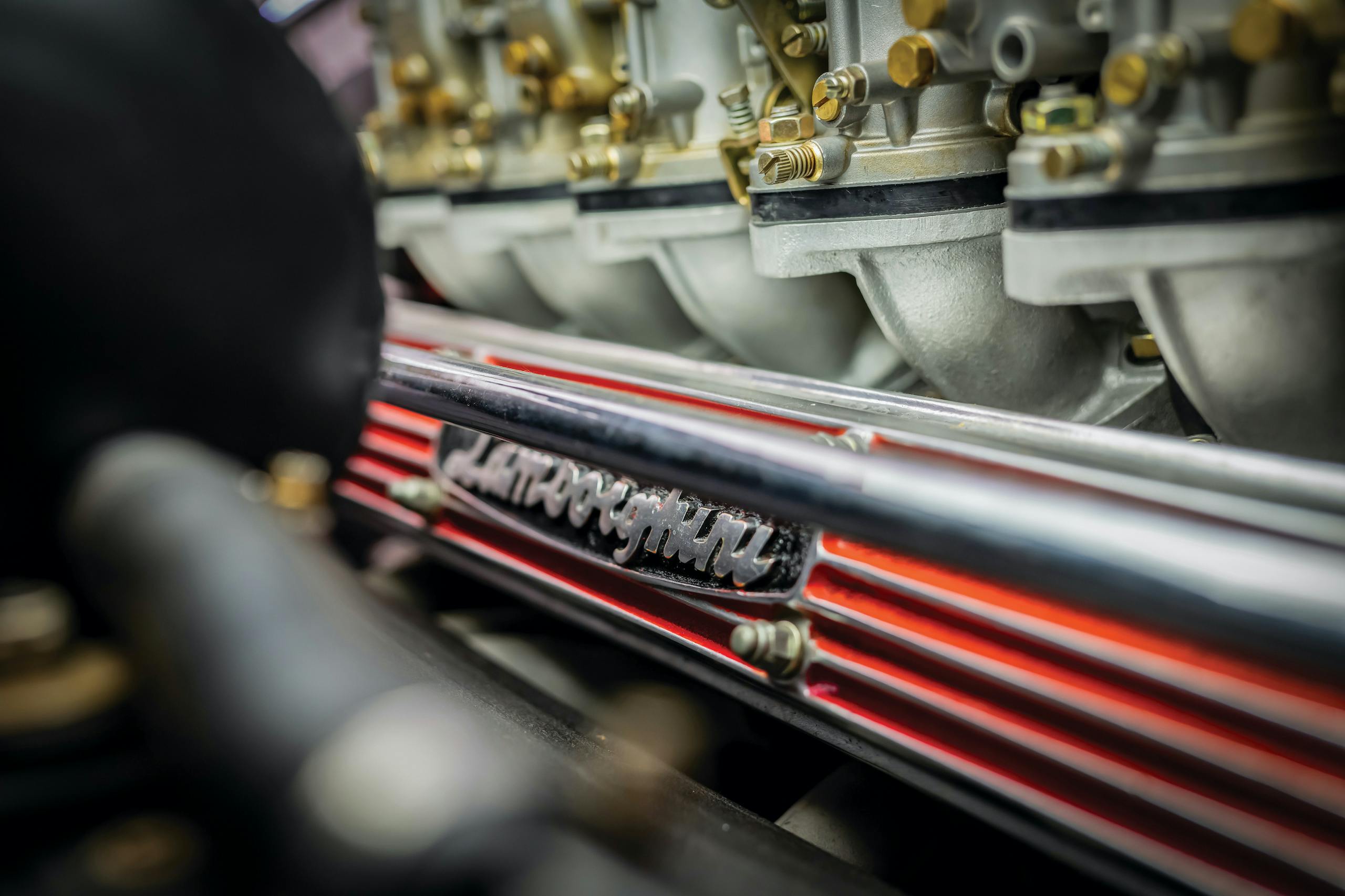

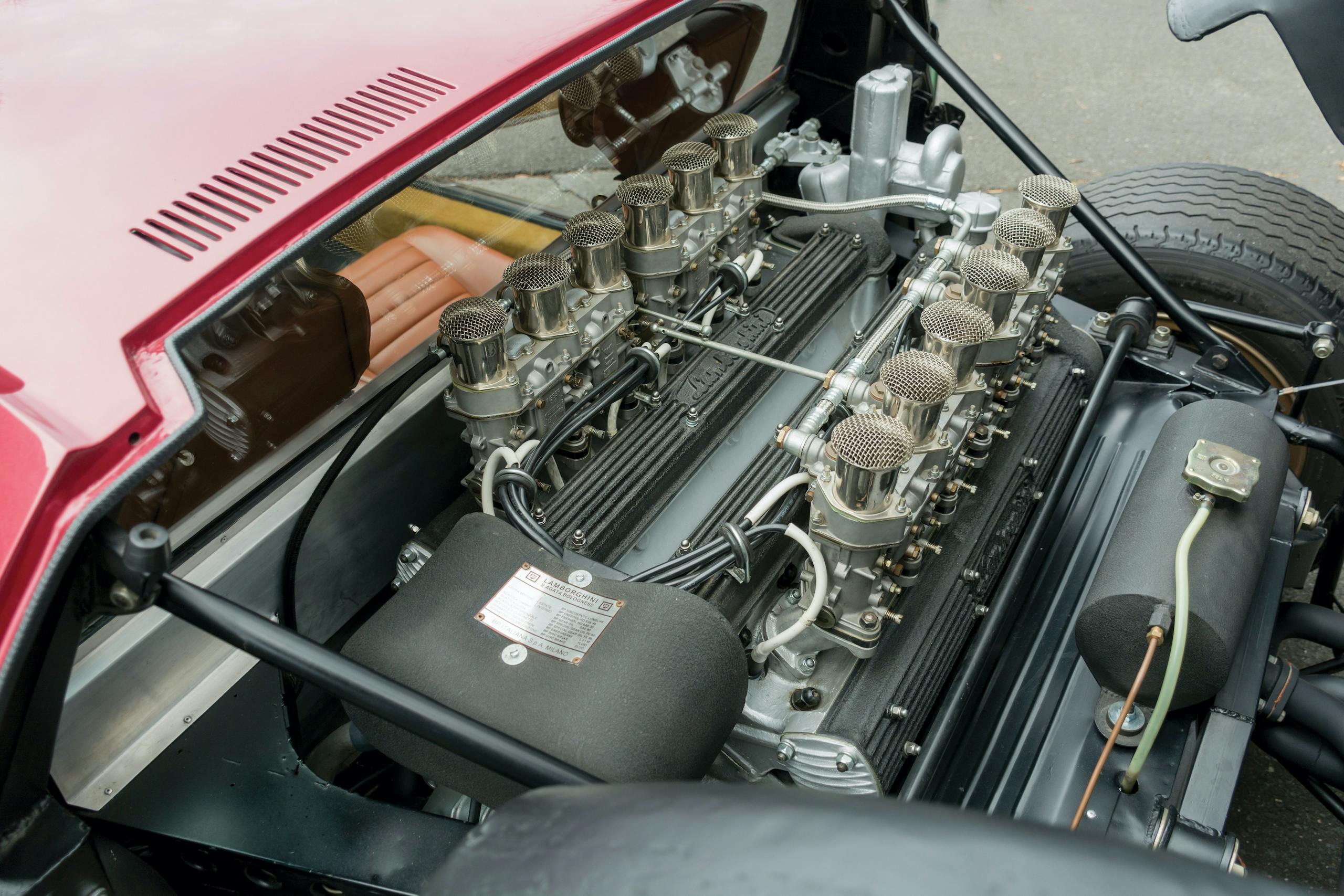

The clever solution was mounting the engine (which was 21 inches wide) transversely, in parallel with the rear axle. This wasn’t a new idea. The Austin Mini revolutionized the world of compact economy cars with its transverse front-drive layout. Honda had tried a transverse engine in its RA 272 Formula 1 car. But Lamborghini was breaking new ground in putting a transverse engine behind the driver in a large performance street car. Due to limited space, Lamborghini also fabricated a transaxle, mounted at the rear of the engine and in unit with the crankcase (like on a motorcycle), meaning the engine and gearbox shared the same oil supply.

Lamborghini presented the Miura’s rolling chassis at the 1965 Turin Auto Show. Even just the naked mechanicals, with the drilled holes in the monocoque and the novel sideways engine bristling with Weber carbs, were enough to cause a stir. Potential customers rushed the stand. Lamborghini, still a boutique carmaker just a few years old, nevertheless continued to think of it as a promotional tool with neither a proper name nor a body.

Carrozzeria Touring, which had styled Lamborghini’s first cars, was soon on the verge of going out of business, but Italy’s other coachbuilders were eager to have a go at Lamborghini’s new sports car. Bertone won the deal and gave the project to Marcello Gandini. Like the rest of the Lambo’s design team, Gandini was a young creative in his mid-20s.

What he came up with was his first big hit (of many). Draped over the low-slung race-inspired frame, it’s a shape that Car and Driver in 1967 called “classical Italian, with just enough sharpness in the fender peak lines, in the American manner, to keep it from looking soft.” Road & Track described it as “an exercise in automotive art for a particularly rapturous kind of driving.”

Lamborghini presented the car for a second debut at the Geneva Salon in March 1966, and it caused just as much of a stir as it had in Turin the year before. It now had bodywork, finished in an eye-catching orange-red. And it had a name —P400—”P” referring to Posteriore (rear) and “400” referring to the engine’s displacement in deciliters. But Ferruccio Lamborghini, a Taurus, also wanted a proper name. He went with Miura, after a renowned breeder of fighting bulls from Seville, Spain. Bullfighting-related monikers have been a Lambo trademark ever since.

Two months after Geneva, the show car served as the ceremonial circuit opener at the Monaco Grand Prix, and the tiny company was at work getting the Miura, for which there was already unexpected demand, production-ready. It would take several more years to work all the bugs out because, dazzling as the Miura was and despite its U.S. price of about $20,000 (enough for five Corvettes), it was far from perfect.

Taming the bull

All Miuras are noisy cars with heavy controls. Fragile aluminum fenders and no real bumpers mean that parking one can be nerve-wracking. The first Miura P400s also came with manual wind-up windows. Not unusual stuff in the 1960s, but they take seven turns to crank and the winders are awkwardly placed. To get at the engine, meanwhile, you have to open both doors and pull a T-handle behind each seat, then remember to push them back in before closing the doors again.

The early Miura P400’s quirks weren’t limited to the cockpit. At over 100 miles per hour the nose starts to generate significant lift. (It also doesn’t help that the fuel tank, which naturally gets lighter as you burn through gas, is located at the front.) A limited-slip differential would have been a welcome aid as well, but the common low-friction oil supply between the engine and gearbox made this upgrade a non-starter. Regardless, none of this prevented people from lusting after the 350-horsepower dream machine once they’d seen it.

The first batch of major upgrades arrived with the Miura P400 S in 1969, which added vented brake rotors, power windows, optional air conditioning, revised rear suspension, and better tires. Higher-lift cams as well as bigger carbs and manifolds also resulted in a bump to 370 hp. The 1969 model also brought the Miura worldwide exposure on the big screen, when a bright orange Miura was featured for the opening sequence (including a crash) of The Italian Job.

The next big changes came with the SV in 1971. Revised rear suspension and a slight lowering of the nose changed the aerodynamics enough at the front to alleviate that pesky front-end lift. Flared rear fenders allowed for wider 15-inch low-profile tires, and the exposed retractable headlights lost their signature surrounding black trim, aka “eyelashes.” New cam timing, larger intake valves, and rejetted carburetors resulted in 385 hp, and later Miura P400 SVs got a split sump, which meant separate oil supplies for the crankcase and the gearbox. This key change made a limited-slip feasible; Bob Wallace gave his one-off Miura Jota a ZF unit and after the fact even added the diff to some Miuras. (Like the Jota, the P400 SV Speciale sold by Gooding & Co. last year had both a limited-slip diff and dry-sump lubrication, neither of which were factory equipment.)

After building 150 SVs, Lamborghini replaced its breakout star with the equally sensational Countach for 1974, a car that would carry the Lamborghini torch for the next 16 years and influence the shape of nearly every Lamborghini since. 1974 wasn’t just the end of the line for the Miura; Ferruccio Lamborghini sold his last stake in the company that year, which led to a string of investors and corporate owners until Audi came to the rescue in 1998.

Lamborghini’s genre-defining supercar, then, was not only the company’s first breakout hit but also the last supercar built fully under the company’s founder. And what had been intended as little more than a promotional tool wound up being one of its most beloved and celebrated models. With nearly 800 built, the Miura outsold the 350 GT, 400 GT, Islero, and Jarama by a wide margin. Nearly 50 years later, the Miura is worth way more than all of them as well.

What is a Miura worth?

The hierarchy of Miura values is straightforward. Built in three distinct series, the car carries three distinct prices, with the first P400 at the bottom, the improved P400 S in the middle, and the fully developed P400 SV at the top. The going rate for an SV is traditionally around twice that of a “regular” P400 in similar condition, but despite its quirks it would be a mistake to assume that an early P400 is half the car. The original is arguably the best value.

Currently, the condition #2 (“Excellent”) average value is an even $1M for a Miura P400, $1.2M for a P400 S, and $2.1M for a P400 SV, while the condition #1 (“Concours” or “best-in-the-world”) values range from $1.3M for a Miura P400 to $2.45M for a P400 SV. Add 10 percent to the value for a car with factory air conditioning, 10 percent for vented brakes on the P400 S, and deduct 10 percent for an SV without the split sump.

Miuras had a big price surge during the first half of the 2010s, even relative to the rest of the high-end classic car market. The median condition-#2 value today is $1.2M, while a decade ago it was $367,000. From 2011–16, the median Miura price was up 167 percent, with early cars up over 200 percent. At Pebble Beach in 2012, an SV with factory A/C and split-sump became the first Miura to break seven figures at auction, coming in at $1.375M. The first Miura to eclipse $2M at auction was at Amelia Island in 2015, with an SV factory promo car bringing $2.31M.

Activity has been quieter lately but has generally trended upward, with a 22 percent overall gain from 2016 to today. Other Lamborghinis have appreciated more since 2016, with the Jalpa, Diablo, Uracco, and LM002 up from 35 to 55 percent, but it’s hard to imagine any production Lamborghini ever being worth more than the standard-setting Miura.

The current world record price at auction for a Miura is £3,207,000 ($4.257M)—the aforementioned SV Speciale with its dry sump and limited-slip that sold at last year’s “Passion of a Lifetime” auction in London. It smashed the previous world record of €2,388,400 ($2.54M) set by another SV back in 2017. British classic car dealer Simon Kidston also recently released a comprehensive book on the Miura documenting every example built, and we know of several Miuras undergoing restoration in California and Texas. Lamborghini’s Polo Storico in Sant’Agata has been offering factory restorations since 2015 as well as original spare parts for classic Lambos. Whether all this attention on the Miura will lead to a glut of them on the market isn’t clear, but the Miura will always be king of the bulls.