Media | Articles

The electric eCOPO Camaro is a real-deal, no-nanny dragster

When Chevrolet released the eCOPO concept at the 2018 SEMA show, a lot of car lovers were unsure what to make of it. We’ve overheard comments suggesting that onlookers believe the electric-powered car is filled with high-tech traction control and that it would take all of the skill out of drag racing. They couldn’t be more wrong.

To get the dirt on the eCOPO, we spoke with Pat McCue from McCue & Lane Electric Race Cars, the shop that built and owns the bright-blue Camaro. Pat’s full-time gig is teaching a high school shop class where he and his students race Shock and Awe, a fourth-gen Pontiac Trans Am that uses a 2004 Jerry Bickel chassis and an electric drivetrain very similar to the one found in the eCOPO. Six times a year they compete in E.T. bracket racing, where driving skill and reading the track are key, and a slower car can win because consistency is rewarded. That’s not to say the eCOPO is slow. With about 750 horsepower hauling around 3200 pounds of car, it will finish the quarter-mile in the nine-second range.

“It’s built just like a Stock Eliminator. There’s no auto shifter, no trans brake.” Pat told us. There’s also no traction control. It’s staged with an electronic two-step activated with brake pressure. The two-step holds the output of the electric motors at a pre-programmed rpm, just like it would in a gasoline car. Once the driver launches the car, shifts are up to them, as the Turbo 400 three-speed automatic has a manual valve body. The eCOPO name is appropriate, because from the transmission back, the electric car’s drivetrain is identical to every other 2019 COPO. “It adheres to all the same rules as a gas car,” Pat explained. Meaning it has the same Turbo 400 transmission and nine-inch solid rear axle with 6.0:1 ring and pinion.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

As similar as it is to the COPO we’re used to, it certainly sounds different going down the track. Pat told us that the driver can hear more gear noise when there’s no loud exhaust to contend with. Even the tire chirp when shifting into 2nd and 3rd can be noticed, which can come as a surprise to a driver who is used to making passes in a gasoline car.

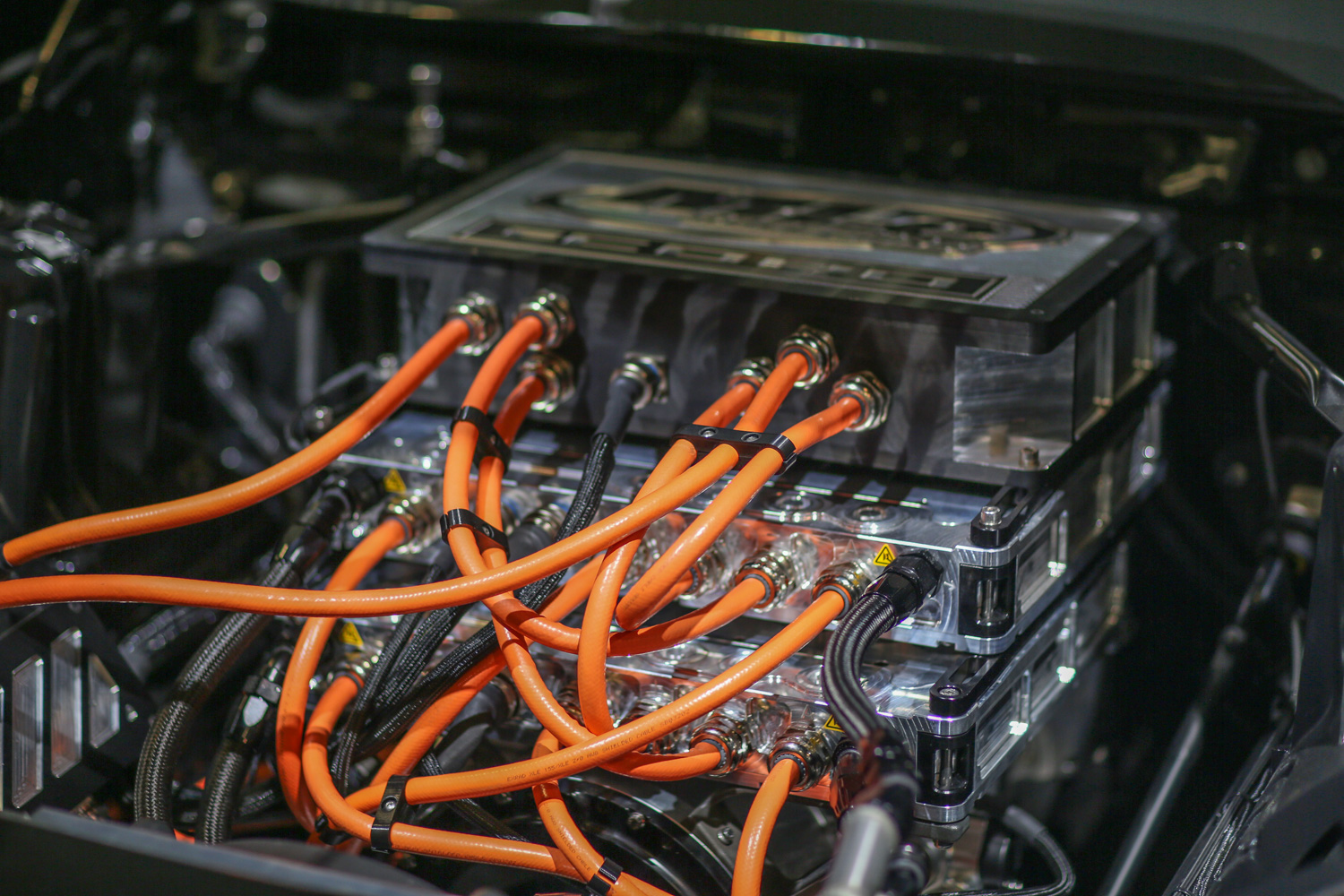

The 750 or so horsepower that the eCOPO currently makes could be upped to 1100 by adding another motor in series, but then the battery becomes the limiting factor. “In order to maintain the voltage, you need fairly large batteries,” says Pat. The huge amperage draw from the twin 700-amp motors at full throttle causes the voltage to sag and an additional motor drawing current wouldn’t help. Battery tech is expanding quickly thanks in part to the demand for electric cars and as batteries get even more powerful and more compact, the eCOPO and its electric racing brethren would be able to benefit as well.

The battery is capable of powering the eCOPO for three consecutive runs, but for consistency they’d prefer to charge after each quarter-mile pass, as it drains 6-7 kilowatts from the 32-kilowatt reserve. The battery is made to charge just as quickly as it drains. Once it’s back in the pits and plugged in, the eCOPO will charge to full in 25 minutes. That’s plenty of time between rounds of racing.

The electric motors take some of the variables out of drag racing, but there’s still reading the track conditions to know how hard the car can be launched, setting up the suspension and tires to get the most traction, selecting the right torque converter, and nailing the reaction time.

The motors, controllers, and batteries aren’t cheap though, and are roughly comparable to the price of a Super Stock or Comp Eliminator powertrain. On the other hand, they don’t require the same maintenance as the average gasoline engine that’s running on the ragged edge. There’s no valvetrain to adjust, for one thing.

McCue & Lane Electric Race Cars plan to run the eCOPO at NHRA in the future. For now, it’s relegated to bracket racing because there’s no other class where it fits.

MLER would like to see that change. Pat wants electric race classes based on power to weight ratio; for him it’s a simple idea, because unlike internal combustion engines that are sensitive to miniscule changes in tuning, electric motors have a definitive power rating. “Volts times amps equal watts, and watts is power.” Of course, competitors will get creative to seek out even the slimmest of advantages.

It is racing after all.