Media | Articles

Driving this classic Mercedes makes you feel like a ’60s star

I am no expert, but I’d argue that even after 60 years on the road, you cannot fully appreciate the Mercedes SL “Pagoda” without two essential ingredients.

The first of these is a thin sliver of a handle, chromed and no longer than a Bic ballpoint pen. Easily mislaid, an SL driver loses it at their peril: This is the detachable, locking handle that is applied to the two roof fastenings on the windshield’s header rail.

The other ingredient required to see what all the fuss is about is, well, sunshine. Admittedly, it’s a little more difficult to manipulate than the roof’s locking lever, but today luck is on our side. The clouds have parted and early April showers subsided, and we have a 280 SL at our disposal.

For that we have Sam Bailey to thank. Bailey is the founder of The SL Shop, near Stratford-upon-Avon in England, and the W113-platform 280 SL is his. The 280 is the final evolution of the W113 platform, which began as 230 in ’63 and grew into the 250 in early ’67 before the 280 wrapped things up on the cusp of ’68.

Even among the sea of SLs of every era that surrounds Bailey’s temple to all things SL, the Pagoda—which earned its nickname from the shape of its hardtop roof—somehow manages to stand out and hold your attention. Encountering it is like looking across a crowded room and meeting the gaze of the partner you instinctively know “is the one.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

It’s 60 years since Mercedes’ W113 first drew a crowd, when it made its public debut at the motor show on the shores of Lake Geneva, on March 14, in 230 SL guise. The car and the thinking behind it steered Mercedes in a new direction, with design and engineering that was a marked step change from that which produced the 300 SL and 190 SL that came before. It’s the Pagoda that has best defined the concept and positioning of the SL ever since.

Let’s not get bogged down in product positioning, though. Especially when there is a 280 SL ready and waiting for a driver.

Back to that roof. With the sun shining, and a smattering of photographs captured of the car with the fabric hood raised, it would be rude not to lower it. Once you have been shown the technique to ensure nothing gets trapped or fouled, folding the top is a straightforward exercise that one person can manage quite easily.

It starts with the aforementioned locking handle, which Bailey keeps in the handy stowage tray between the seats. Latch it in turn to each fastening, twist to release, then get out of the car and walk around to other side, where you reach behind the passenger seat, pull a release lever for the rear of the roof, fold up the back—taking care not to crease the plastic window—then pull back and lower the rest of the roof frame, folding carefully as you go. With two people, it’s the work of no more than 30 seconds. With just a driver, there’s a little more to-ing and fro-ing.

It packs away out of sight beneath the rear deck, which fastens securely in place, assuming you followed the procedure correctly and didn’t jam anything along the way.

What was already a handsomely proportioned car is somehow elevated to a whole other level of style. The shallow body appears barely any deeper than the vertical headlight clusters. The shark-nose with that three-pointed star placed confidently on the grille hints at sporting intent without thrusting and gesticulating like a Jaguar E-Type, an impression further helped by Mercedes’ signature bonnet bulge. The boot lid tapers to a lower point than the rear wings, again adding a subtle hint of dynamism to the mix. The Pagoda is at once simple yet supremely confident, and of course, with the roof down the world can better peer at whoever is behind the wheel.

For the countless daytrippers and residents of Stratford-upon-Avon, it is likely to be disappointing that there’s a nobody at the wheel. People don’t just look at a roofless SL Pagoda; they smile, point, nod, or suck in air through their lips—sometimes, somehow, all at once.

In the Pagoda’s day, they may well have spotted a famous figure in the driver’s seat. The W113 was very much a plaything of the rich and famous. It cost nearly twice as much as an E-Type in Britain, because of import tax, and names associated with the car at the time read like a who’s who of Hollywood and rock ’n’ roll royalty. John Lennon, Sophia Loren, George Harrison, Stevie Nicks, and Stirling Moss all enjoyed their stints at the wheel. Moss went so far as to declare, “In all the years I have been driving, I cannot remember ever driving a car that I would have liked to own more.”

It’s certainly a hugely appealing cabin. Here lies a lesson in ergonomic knowhow: The driving position, the placement of the switchgear and Becker Grand Prix radio, the visibility of the VDO dials, the virtually-uninterrupted view in all directions—everything comes together to put you at ease. Try parking one of these in a tight spot, then attempt the same in an E-Type. You’ll quickly come to be thankful for the Germans’ ever-sensible way of doing things.

And as boring as it may sound, that attention to detail extends to making the Pagoda practical. For two, it is spacious, brimming with stowage space. The surprisingly large boot caters for an era when trans-continental travel by car was still the discerning, desirable way to proceed. With the roof down and American Optical sunglasses in place, naturally.

Actually, there’s one more thing you need to do when driving an SL Pagoda—wind down the windows, and rest your elbow on top of the door. Because while the SL held its own during contemporary independent road tests and endurance rallies, and its name (SL stands for Super-Leicht, Super Light) suggested a car of a deeply sporting bent, there is no finer pleasure to be had than sinking into the thing and just relaxing, feeling—no matter how fleeting the moment—your worries leave you behind in the air tumbling behind the car.

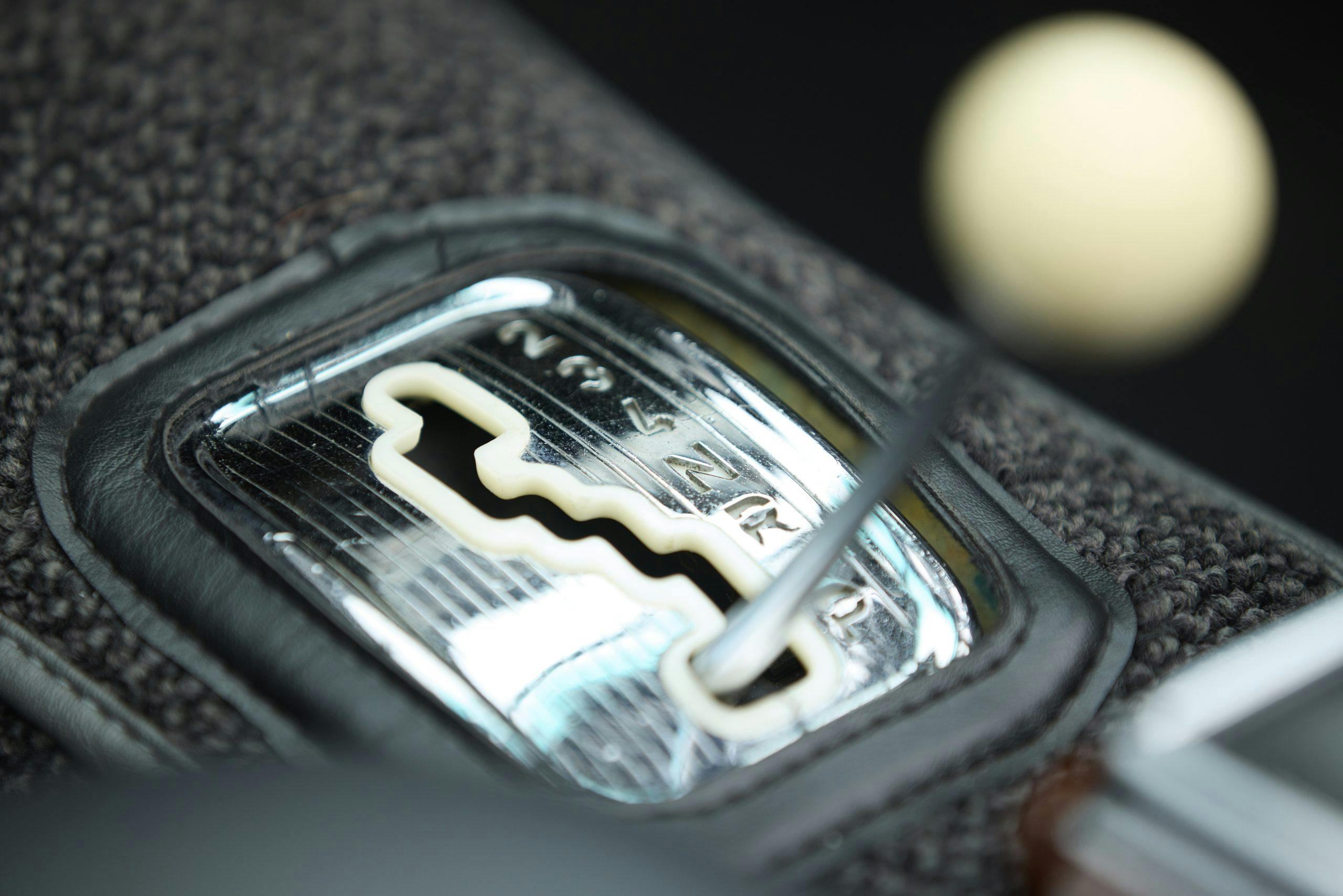

The 2778-cc straight-six engine, said to be good for almost 170 hp in its day, has a playful rasp between 1500 and 2000 rpm. Generally speaking, though, the four-speed automatic gearbox likes to shift up at 2500 rpm. Persuading it to kick down and hold a gear to experience the snarl at 4000 rpm takes some doing. When the 280 SL does pick up its heels, it’s pleasing to find that it takes corners in a flat, surefooted fashion, the open diff ultimately spinning away any excess of power over traction. However, such spirited conduct feels out of place behind the wheel of this most stylish of Mercedes.

Today, this is not only a car, but likely for many an achievement—perhaps a reward for selling your business or a car that has been handed down from one generation to the next, with the simple instruction to enjoy it before repeating the exercise for your own children in years to come. Like many Mercs, it also feels ripe for—whisper it, for fear of upsetting fans of preserving originality—conversion to electric propulsion.

The original 190 SL and 300 SL models were conceived thanks to the continual pestering of Max Hoffman, the importer of Mercedes in North America, who convinced Fritz Könecke, the general manager for Mercedes-Benz, that drivers in America expected a sports car from any prestigious brand. He got his way, with the pair of SLs making their world premiere at the International Motor Sports Show in New York, on February 6, 1954.

Nine years later came the SL Pagoda that, arguably, best defined the role that the car had to play. Nearly 50,000 would be made in total, and today a W113 is a sought-after classic car that appeals to enthusiasts and collectors alike, with the best of the 280SL breed valued at nearly $200,000. Naturally, that will be a concours example, and this icon of our times can be found for considerably less. See for yourself by browsing the Hagerty Price Guide.

Whichever end of the W113 market you find appealing, make sure of one thing—that the car comes with that locking handle for the roof. Because no matter what a sales person tells you, they definitely can’t arrange for sunshine.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Via Hagerty UK

I love these cars — so elegant and understated.

Here in the U.S. the term “Merc” means Mercury.

Mr. Mills- Not for any fear of disrespecting originality, but conversion to “electric propulsion” would just suck-out the very soul you were praising. That fuel-injected inline six is work of art and visceral animal. Any EV, however powerful, is simply a lifeless appliance. Add batteries for a complete disruption of the power-to-weight ratio responsible for the SL’s delicate handling. You may, (at times) be a creative writer, but automotive engineering is not your forte.

Had a 68 Eurospec 280 SL. Lovely car but not especially dependable. Lots of fuel injection problems, rust problems, brake problems, the top leaked like a sieve. Have a CLK 350 now, a much, much better car (40 years of progress will do that), but the 280 SL is still prettier. I’ll have another, please.