Media | Articles

Don’t judge a classic’s worth by its crumpled sheetmetal

My neighbor turned off his lawnmower, hopped the little fence that separates our properties, and walked toward me with a perfect blend of confusion and fright on his face. Even his border collie looked puzzled.

“Are you … going to fix that up?”

He pointed to the mangled remains of a Fiat 850 dumped next to a van-sized pile of uncut firewood by the side of my house. “No, it’s a parts car.” “Oh. Is there anything usable on it?” Not at first glance, but a friend and fellow Citroën enthusiast who showed up two minutes later in a gorgeous 1966 2CV provided the answer. He kneeled, slowly opened the bent hood of the Fiat, and said, “I don’t believe it. Everything looks new.”

I didn’t believe it, either. I spend more time doom-scrolling than I’d like to admit, but I browse the classifieds in search of classic cars instead of looking through vacation photos posted by someone I haven’t spoken to since I was 17. One night, I saw an ad for a Fiat 126 located an hour south of my house, which is in southeastern France.

The seller included three photos: two showed a Fiat 850 sedan—certainly not a 126—that looked like it narrowly escaped the crusher, and a third showed an odometer displaying precisely 10,248 kilometers (a little under 6400 miles). It’s a five-digit odometer, so I was certain that 10,248 kilometers actually meant 110,248 kilometers. Curiosity got the best of me. Contact seller.

The seller’s directions took me to a long, narrow field that looked like a private junkyard. I spotted a first-generation BMW 1 Series registered in Portugal, the expected assortment of white, car-based Peugeot and Renault panel vans that have commandeered the French countryside, and a Suzuki Vitara from the 1990s. My gaze followed the trail of dead cars and landed on the silhouette of an 850, basking in the soft morning light at the very end of the row.

Even from 100 feet away, I could tell this car had been involved in a gruesome accident. What intrigued me was that, from the same distance, I could tell that it wasn’t very rusty. I own a 1971 850 sedan, and I simultaneously owned a 1971 850 Spider and a 1971 850 Bertone Racer in the late 2000s, so I’m all too familiar with the model’s heroic ability to rust. That’s one reason why Fiat left the American market in 1982: A former mechanic told me that in some states, such as Utah, Fiat had to buy cars out of junkyards because they were still covered by the factory rust warranty but too rusty to be on the road.

I almost turned around and drove home, but I had driven an hour to get there, and the seller was already on his way. He told me the story of the supposedly low-mile Fiat as we walked up to it: He runs a metal recycling business (hence the mass grave of 20-something-year-old cars in the negative zone of their depreciation curves) and had dragged the 850 out of a barn after someone asked his help in clearing it out. Someone had rolled the car, which explained the damage. These, along with other cars of the late ’60s and early ’70s with rear-mounted engines, spent entirely too much time upside down, especially if they were put in the wrong hands and taken down a mountain road.

What was more surprising was when it rolled. The seller didn’t know the model year of the 850, but there was a 1969-issue plate on the back and a dealer sticker suggesting that the registration number was likely original; it was sold new in this area. The person who crashed in the ’70s survived the incident, stuffed the car in a barn, and spent decades entertaining the idea of fixing it. Gradually, the improbable story told by the odometer began to sound plausible.

But, wow, what a crash! I wouldn’t have wanted to find myself anywhere near the Fiat when its rear wheels went airborne. The dent in the roof was so deep you could pour water into it and raise fish. Wiring kept the driver’s door from opening. The passenger side had obviously hit something tall, thin, and stationary (probably a pole or a tree) that re-stamped the rocker panel into a C. Any repair is possible if you throw enough money at the problem, of course; but unlike a ’50s Ferrari, a car as mundane as an 850 wouldn’t reward such an investment.

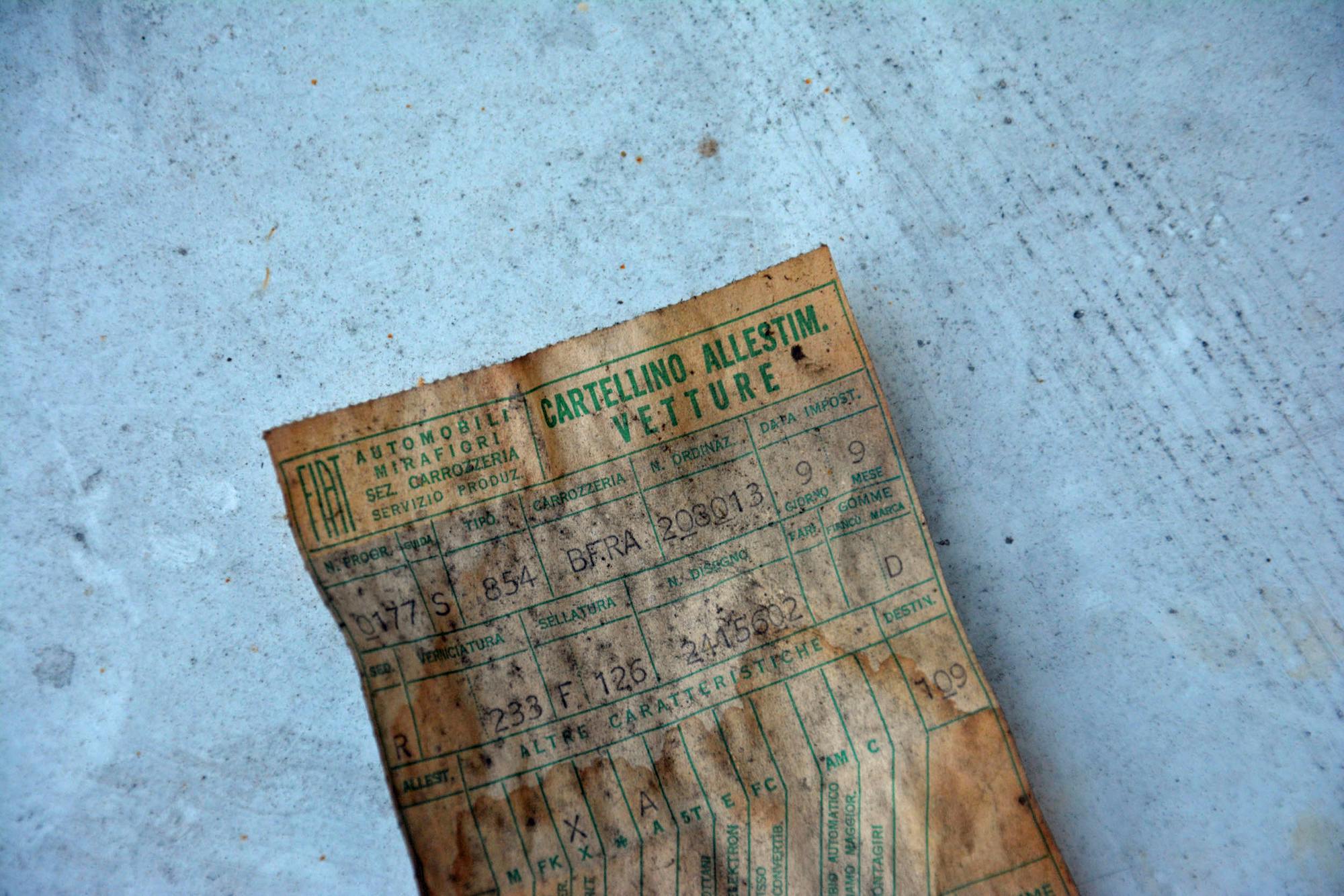

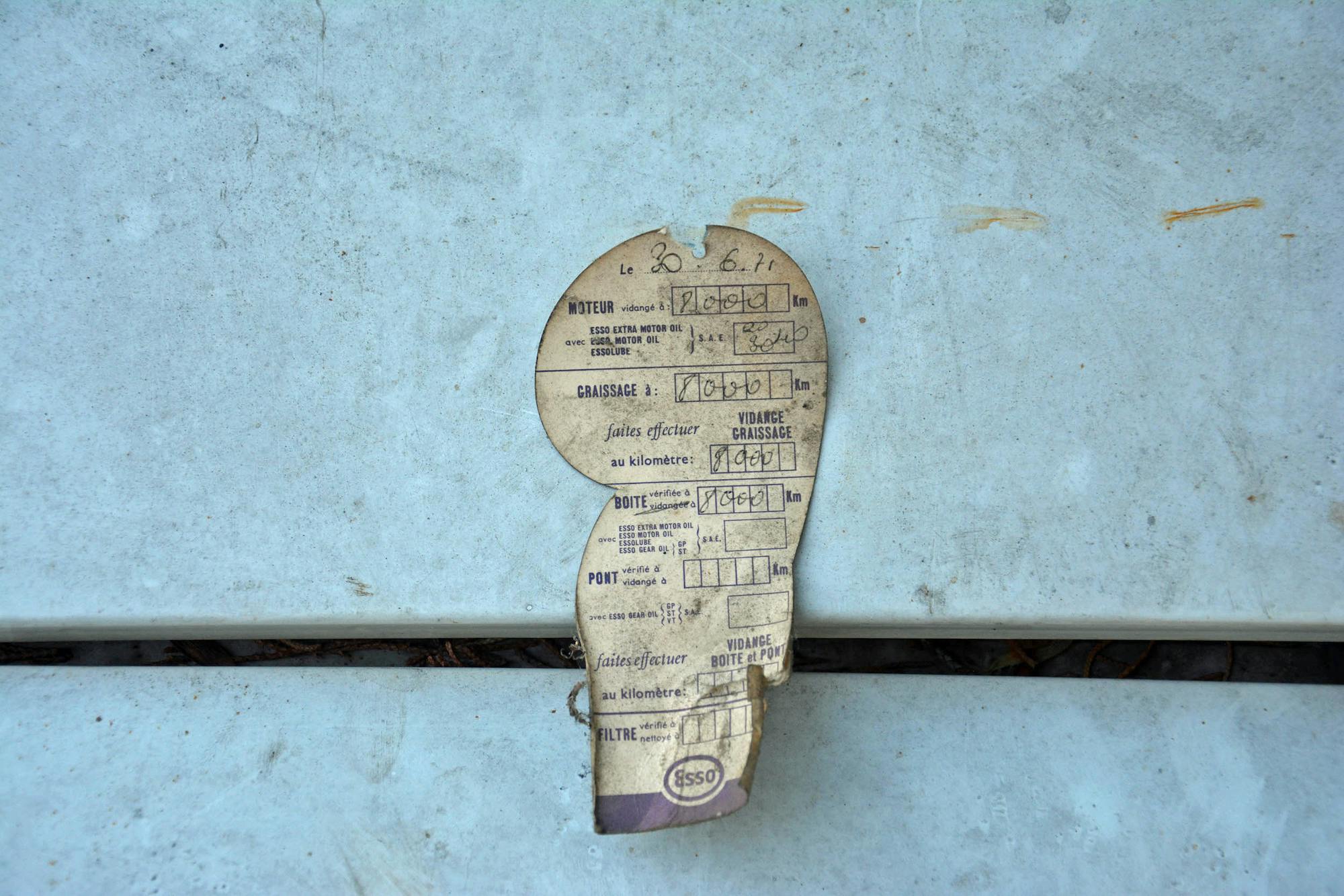

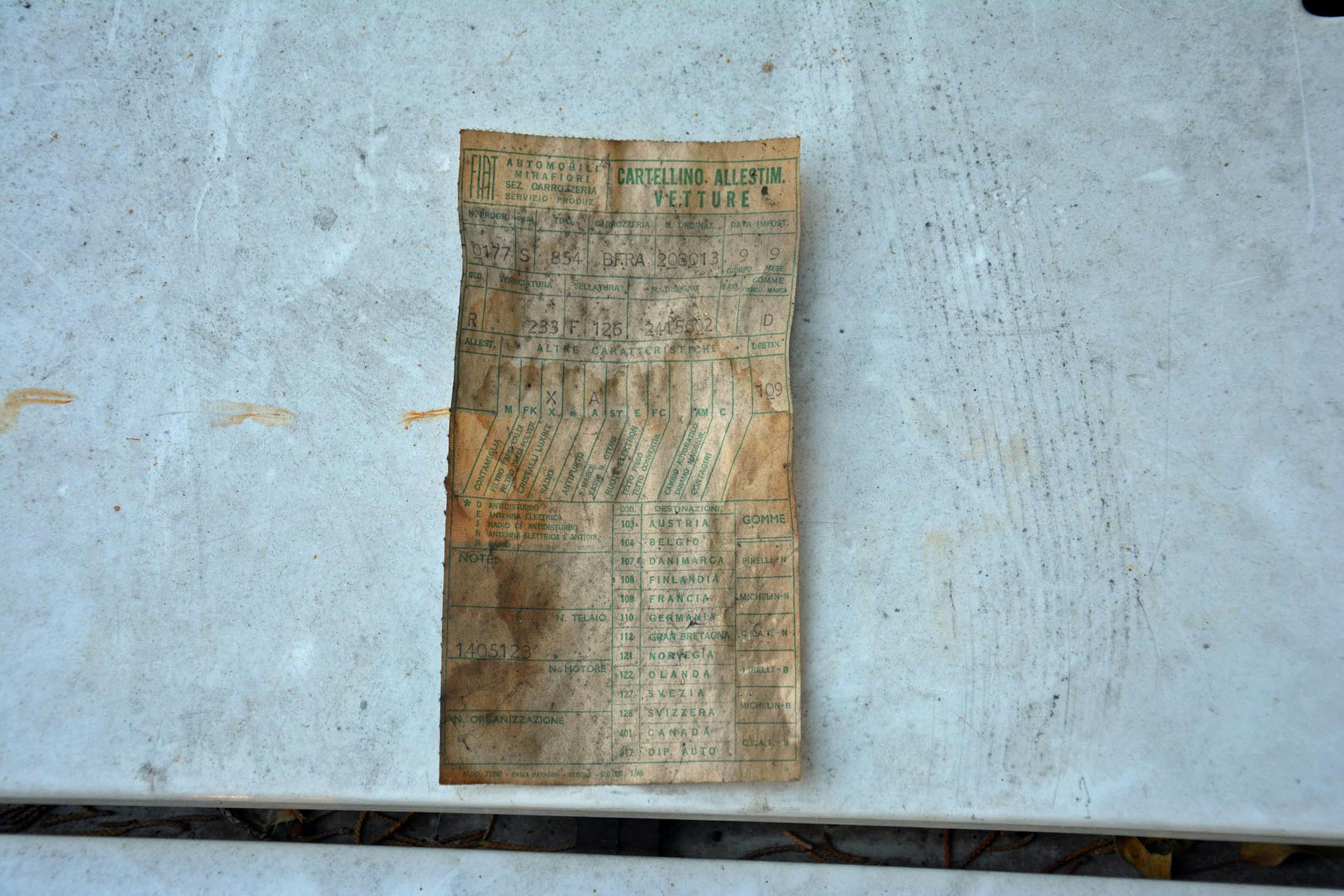

I decided to investigate, beginning with the interior. The front seats were gone, the floors were cut out, and the windshield lay against the rear bench seat. White over red—this 850 must have been gorgeous before it tried landing a backflip. I discovered the factory build sheet (!) and, inside a trunk that looked like it had never been used, a bookmark-shaped piece of paper detailing an oil change at 8000 kilometers (4970 miles) in June of 1971. Even the battery tray, one of the most rust-prone panels on a rust-prone car, was pretty solid. The washer fluid bag and the rubber strap that holds the spare wheel were as good as new.

One peek into the engine bay sealed the deal: The 850 looked like a late-model car (Fiat built the 850 through 1973), down to the maintenance stickers and the factory markings on the radiator. It was fascinating. I’m 34, so the 850 was already old by the time I was born and already a classic by the time I got my driver’s license. I had only seen this stuff in brochures and repair manuals. Wiping off a thin layer of dust and grime revealed a shiny carburetor. The generator vacated the premises long ago, but beyond that the drivetrain was complete and untouched.

I stopped worrying about the mileage and began worrying about how to get the car home. As luck would have it, the seller planned to pick up a car a few of miles north of me the following Monday and offered to drop off the 850 on his way up. Sold! This monument to the dangers of heavily rear-biased weight distribution now sits behind my second-generation Volkswagen Golf, staring at the very mountains in which it was crashed.

What’s next? Well, here’s the catch: There’s nothing that I need from this car. It was simply too good of a deal and too good of an opportunity to pass on. Because these cars were mass-produced and mass-destroyed, finding 850 parts has become difficult and surprisingly expensive, so this one will get condensed into a stash of spares neatly labeled and stored in boxes in my garage. I’ll save anything worth saving, from the full drivetrain to odds and ends like the spare-wheel strap and the glass. A voice in my head is even telling me to chop off the front end and turn it into a bar. Put the lights back in, install a countertop and a handful of shelves, and build a frame that bolts to the front bumper’s mounting points …

Doable? Yep. Easier said than done? You bet. Even if this 850 never settles down in my living room, the parts I’ll keep in my garage will make getting my 1971 back on the road and keeping it there much easier.

So, to answer my neighbor’s question: Don’t judge a lightly used classic car by its crumpled sheetmetal.

***

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I had one of these (can’t remember if it was a ’70 or ’71, I think the latter) – and I loved it. As I looked through these pictures, I was once again reminded of how much fun I had in that car. I know you can’t go back again, but if I could, I’d do it in that little 850!

I had a Datsun Fairlady roadster, I loved when I was in the service, but had to sell it. Years later, many years later, I saw one for sale. I eagerly climbed in, only to find I could not fit in it. When I was 19, I weighed 130lbs.

50 years later, I weigh considerably more. Couldn’t get under the steering wheel. Oh well……

Very cool. I owned a ’67 850 Coupe for a few years, which I still think is one of the greatest small car designs ever. I sold it after realizing it was too terrifying to drive in today’s perpetually distracted traffic.

You really need to look up the meaning of the word ” Classic “

If you want to make it run I say why not. After all people are desiring Renault Fuego’s for some reason.