Media | Articles

Decades before hot rods, Americans built “gow jobs”

When Dominic Palazzolo’s highboy Ford Model A Roadster rolls into a cars and coffee or a cruise night gathering, he can be pretty sure he’ll have the only “gow job” on the premises. What on earth is a gow job? In brief, it’s a stripped-down high-performance automobile built and equipped as it might have been in the early 1930s. In other words, a prototypical hot rod.

Most of today’s automotive enthusiasts peg the birth of the hot rod in the late ’40s or early ’50s, when returning G.I.s, bursting with pride, energy, and dollars they’d been unable to spend on the battlefield, embraced four-wheel excitement in the form of cars modified to look good and go fast. Quite often, the object of their affection was one of the abundant and inexpensive machines of the ’30s, usually a V-8 Ford Model B, and quite often a roadster. While this performance revolution undoubtedly kicked off the post-war hot-rod craze, it wasn’t the first time America had fallen in love with fast cars. The fathers and grandfathers of the ’50s rodders took a high-speed turn at the wheel as well. And at least for a time, their cars were called gow jobs.

I had never heard of gow jobs until I met Palazzolo at a “Parking at Pasteiners” gathering on Metro Detroit’s Woodward Avenue and did a little research. “Gow,” I learned, was a slang term for opium, in the wild and crazy days of the jazz age. At the time, the drug was used to hop up racehorses. Since the cars of the ’20s were only a generation removed from the horse as a primary means of transportation, gow job was an obvious choice of terminology when it came to describing automobiles modified to perform better than factory-issue vehicles. “Hot rod” was both a term and a notion still far in the future.

The first gow jobs were Ford Model Ts, but the more advanced Model A became the vehicle of choice in the late ’20s. Modified carburetors, higher compression ratios, and larger displacements, along with a variety of other techniques, served to increase the horsepower output of the four-banger engines. Removal of extraneous body parts, like fenders, interior trim, and even windshields made the machines lighter. Roadsters could be driven on the street, yet they were light enough for competition. Some of the most serious racers went even further, creating “speedsters” that were stripped of all sheetmetal save the cowl and cockpit.

Of course, grandpa had to test his machine in competition, and for the Southern Californians who led the charge, the venue of choice was Muroc Dry Lake, now part of Edwards Air Force Base. Situated in Antelope Valley, just 100 miles north of Los Angeles, it was close enough for a day trip, even in a modified car. At Muroc, the expansive and sunbaked lakebed provided ample room for acceleration, and the young daredevils pushed their modified machines to speeds that Henry Ford had never intended.

Most of the competition results weren’t recorded. At the time, no one suspected we might be interested in learning more about their speed contests almost a century later. But there are records of a few events, including one held in 1931. At that meet, the winner was Ike Trone driving a 1929 Model A Roadster. Trone’s Ford four-cylinder had been fitted with a Riley cylinder head, dual carbs, and various other goodies, supplied by nascent SoCal speed shops, some of which would eventually become part of the huge California automotive performance industry.

Palazzolo might never have owned a Model A gow job were it not for his long-time friends, Keith and Judy Allen. The Allens are Model A aficionados, senior citizens, and restoration experts. They’ve repaired and refurbished many a stock Model A for car owners across the country. In fact, one of their Model A coupes, a rusty unrestored survivor, was once displayed at Hagerty headquarters in Traverse City, Michigan. Devotees of traditional Ford performance, the Allens have hopped up early Fords to varying degrees, ranging from slightly warmed over to hot as heck. While much of their work has been for customers, they have also built several cars to satisfy their own Model A cravings, including a stripped down, hopped-up gow job that they cobbled together about 14 years ago.

The Allens, with an almost obsessive love of the Model A, would never butcher a survivor car, so for the gow-job build they picked up parts where they could—here, there, and everywhere. Knowing the Model A community very well, they were able to locate pristine Model A body parts in the Irish Hills area of Michigan. A sheetmetal expert who specializes in prewar Fords assembled the panels using original Model A rivets.

A chassis was purchased from another supplier of Model A hardware and was fitted with rebuilt original parts, including brakes, steering, and drivetrain. Judy Allen scoured swap meets, picking up parts here and there. The transmission and rear end were rebuilt using stock Model A parts. An old engine that had seen many miles of service was mildly modified and installed in the chassis.

Keith and Judy Allen drove the assembled car for a while, occasionally pushing it to its limits, and its old engine predictably gave up the ghost. That opened the door for a fully rebuilt, more extensively modified engine, or as they were called back in the day, a “banger.”

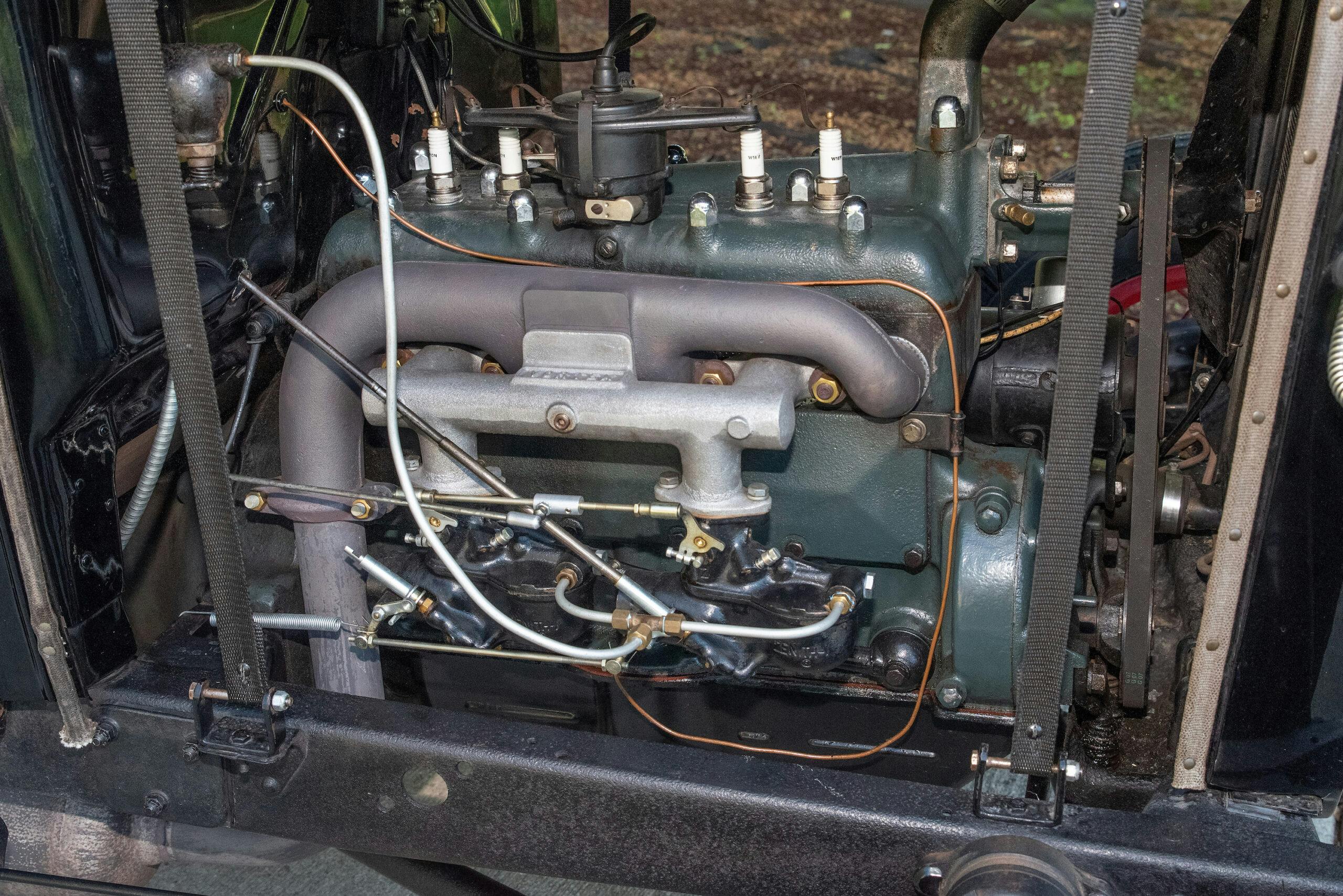

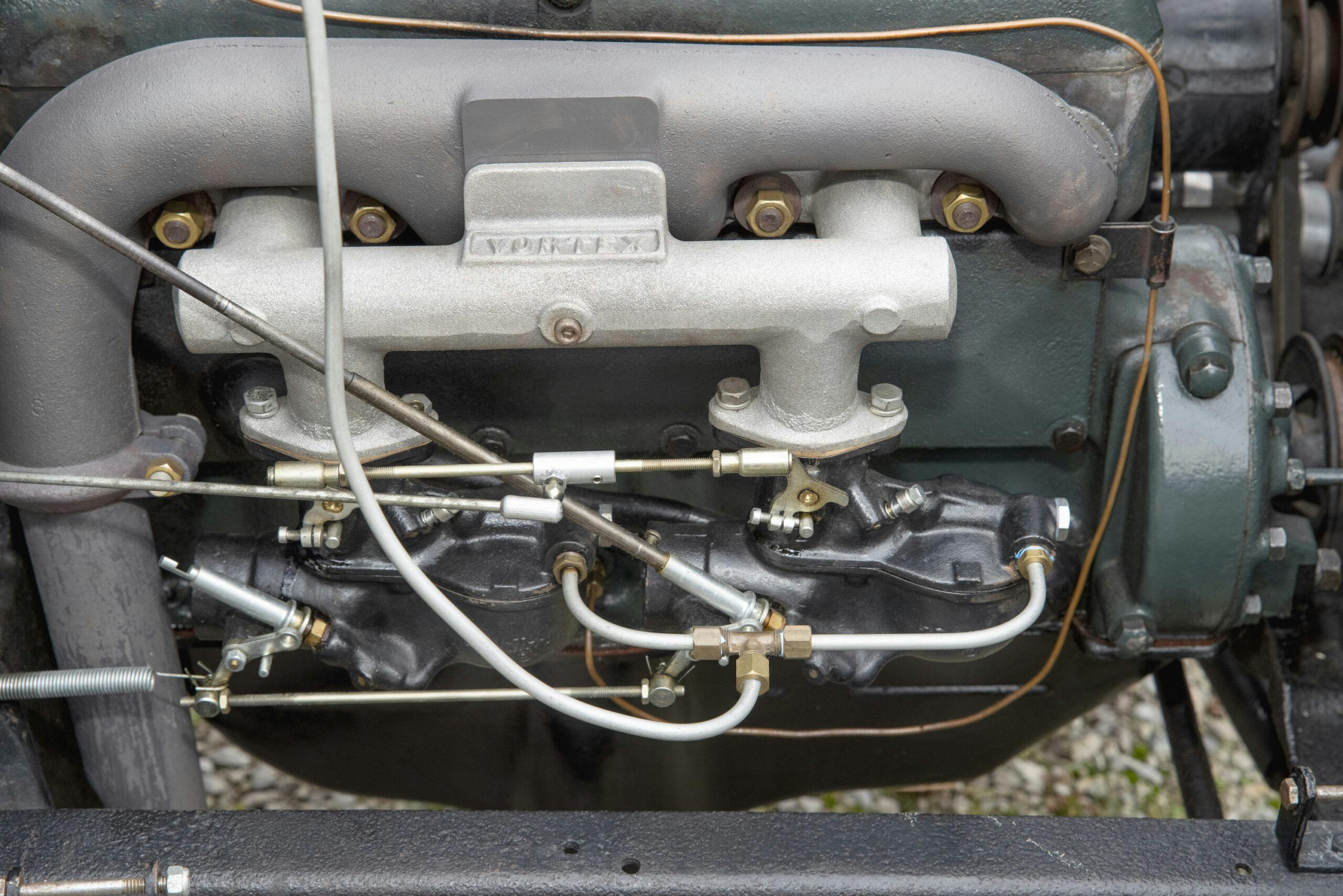

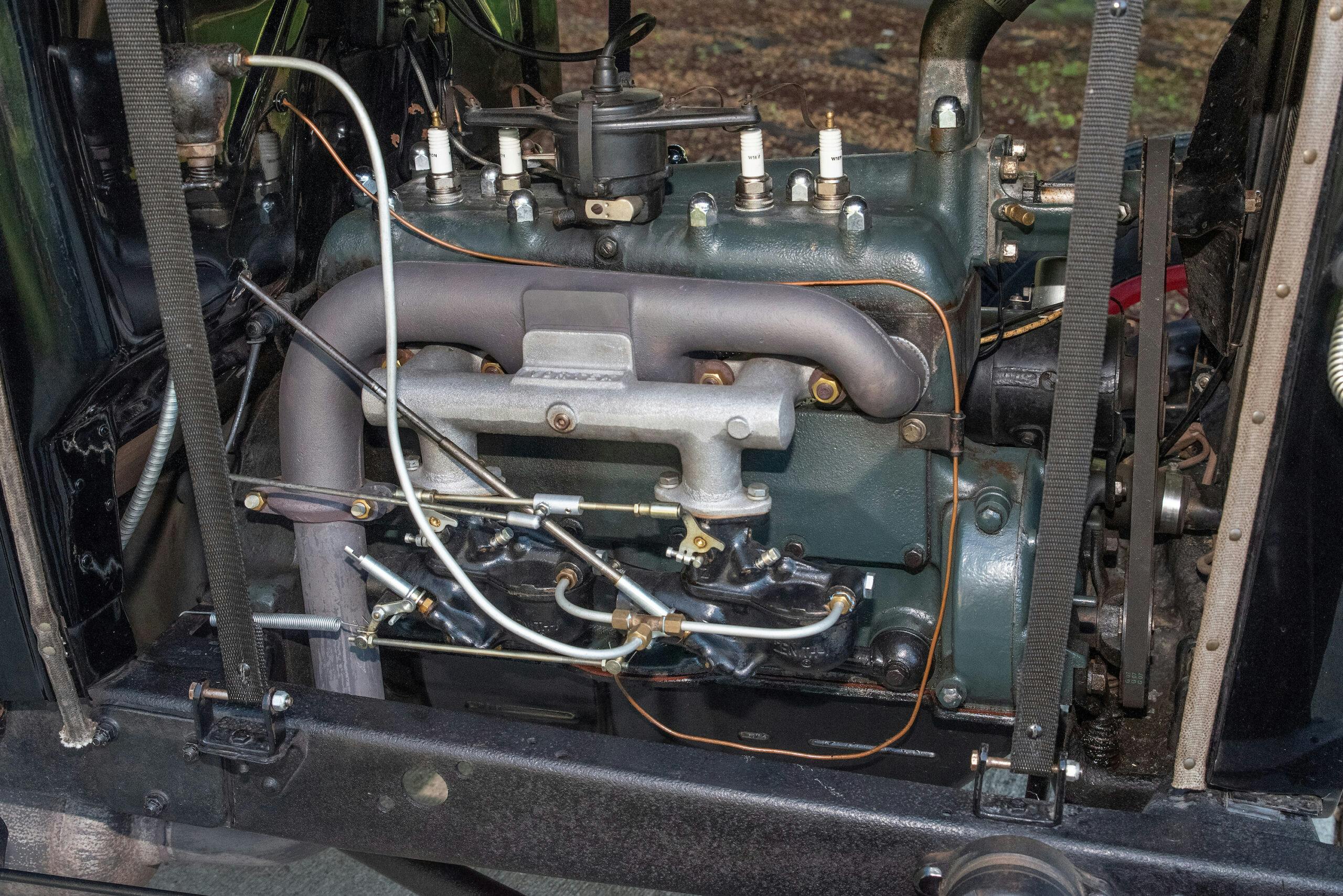

Allen’s Model A experience had taught him that pistons from a 327 cubic-inch Chevy V-8 would work nicely in Model A cylinders, once overbored to 4 inches. That yielded a displacement of approximately 216 cubic inches. Aftermarket Model A pistons are available for a 4-inch bore, but used Chevy pistons are less expensive and lighter. An overbore increases the compression ratio, and to boost it further, the cylinder head was milled. A camshaft with a bit more lift and duration was installed, along with stainless steel valves. The stock intake manifold with its single updraft carburetor gave way to two Zenith carbs on a Vortex manifold. To enhance the engine’s high-rpm capability, Allen machined 13 pounds off the flywheel and installed a later-model Ford clutch and pressure plate. The vast majority of the parts that went into the engine and drivetrain would have been available to a 1930s enthusiast building a gow job.

Palazzolo and the Allens have been friends for many years, so it wasn’t long before he saw the roadster and fell in love. The Allens were reluctant to part with the car but their friend was persistent, so they agreed to sell him the car—with stipulations. It could never be equipped with a V-8 engine and no changes to its configuration could be made without the approval of the Allens. Although Palazzolo had no intention of modifying this very special car, he understood why his friends wanted to safeguard their baby.

With the Model A tucked away in his garage, Palazzolo made a few allowable modifications. First, he revamped the interior, replacing the Model A bench seat with what we would call bucket seats from a Ford Tudor. Back in the day, they were called “jump seats,” because moving from one seat to the other required a jump of sorts. He also added a folding canvas top, an accessory considered unnecessary by dry-lake racers, but a nice addition for a Michigander who might encounter nasty weather on the road.

Like many of us who are very fond of an automobile, Palazzolo drives his Model A with caution, but he has occasionally had it over 70 mph on those narrow bias-ply tires. That can get exciting given the way those tires squirm, but that’s not the kind of excitement he enjoys. Both he and Allen think the car is probably capable of 80 mph. That would be downright thrilling. They know the dry-lake racers of almost a century ago would approve.

***

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

At 80, I had never heard that term gow, now I have, never too old to learn. Good article.

A few years back, I owned a 1930 Model A coupe with a 4 inch drop axle, a “banger” with a Lion head, Mitchell Overdrive, with a free flowing exhaust manifold and a Weber downdraft carburetor, 7:50 tires in the rear, 5:50 tires in the front, lowered headlight bar, and ’35 Ford wire wheels with whitewall tires. That car would cruise nicely when you put it into overdrive. I miss that car!

This is a great story. I have been wanting an old Model A for some time. I am very interested in rebuilding a flathead to see what can be made, NOW I know, THNX…