Media | Articles

Chrysler’s nuclear-powered tank was the height of Atomic Age optimism

The 1950s were unquestionably the best era to be an atomic-energy booster. With the American government scrambling to find new uses for the nuclear genie it had unleashed, the United States threw enormous sums of money at programs both military (nuclear submarines, ballistic missiles, atomic aircraft) and civilian (power reactors, plus Operation Plowshare’s reservoir-digging and gas-mining demolition munitions).

The cash flew fast and loose and into the hands of any almost any individual or corporation that could assemble a credible presentation for harnessing the power of the atom. One of the beneficiaries was Chrysler, a major industrial partner for the American military. The carmaker had previously helped develop technologies as diverse as tanks, Redstone missiles, radar-guided artillery, aircraft engines, and even uranium enrichment for the production of the nation’s first atomic weapons.

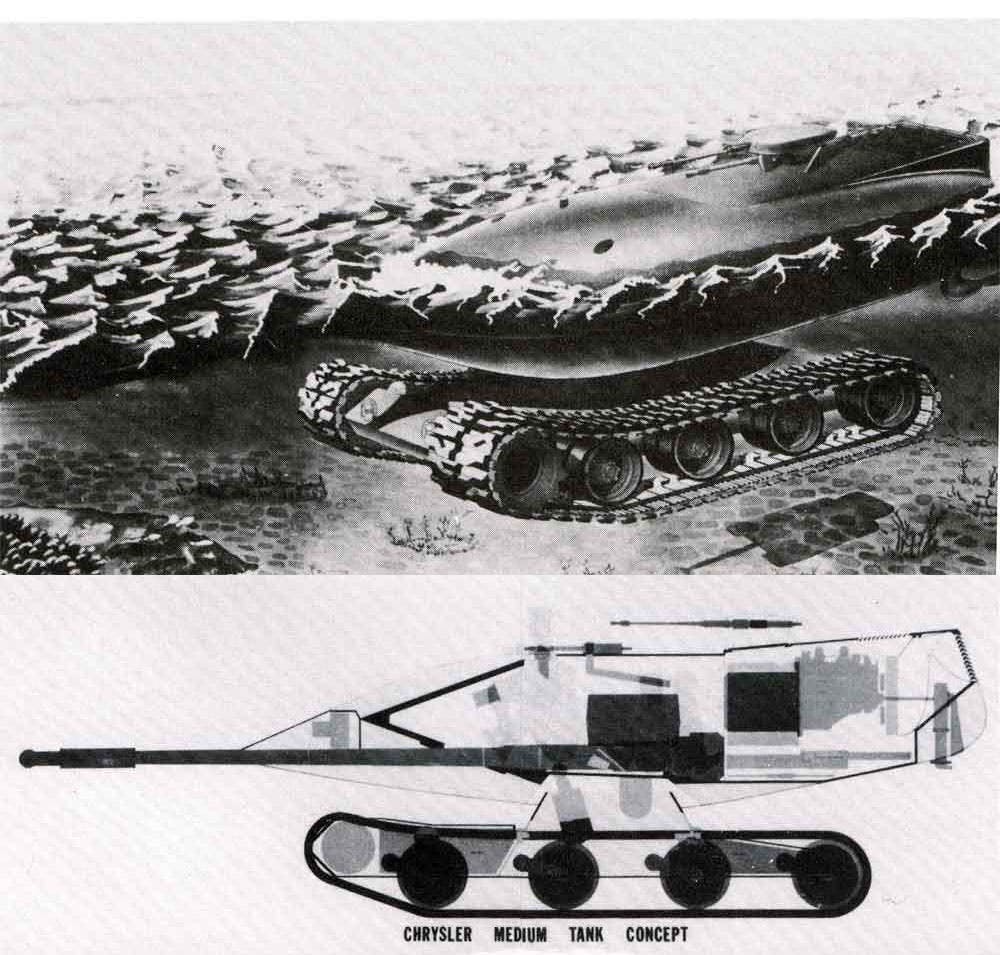

In that light, Chrysler elected to combine two of its previous dalliances—army tanks and nuclear fission—into a single effort that perfectly encapsulated the spirit of the time. The Chrysler TV-8 was a 25-ton tank that could roll on treads or jet through the water, all while lobbing 90-mm munitions at the enemy.

Oh: And it was powered by a nuclear reactor.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

A nuclear-powered what?

Anyone with even a casual interest in military history knows where this story is going. No army has ever deployed a land vehicle motivated by nuclear power, let alone squeezed a functional reactor into a package as tight as the inside of a tank. Back in 1955, however, no one at either Chrysler or the Defense Department had reason to think the idea wouldn’t work. As such, when the automaker proposed the TV-8 as part of its ASTRON project, few batted an eye. Nuclear power was simply one of a few mooted powertrain options.

ASTRON was part of an effort to predict the tank of the future by giving arms designers free reign to assemble whatever they felt was most effective on the battlefield, without any constraints based on past tank designs, production requirements, or weapons and crew needs. The program produced a number of tank designs of varying size, but the TV-8 was by far the most unusual.

To start with, the TV-8 put absolutely everything—engine, armament, crew—into its turret. The chassis below was significantly lighter and more compact than usual. Where traditional tank design generally split the load between the two sections, the TV-8’s turret weighed 15 tons. It rested upon a treaded platform that checked in at just 10 tons. The full assembly weighed slightly more than half of a similarly sized Sherman tank of the era.

Part of the logic behind this top-heavy focus had to do with giving the turret a shape that could better withstand the blast wave of a wartime nuclear explosion. Instead of the square-and-flat armor of other tanks, the TV-8’s turret was podlike and rounded, with a lighter skin wrapped around a heavily protected inner core. The sharper profile was thought to help the tank deflect incoming shells. The turret was also water-tight, with an outside video feed for navigation, and buoyant enough to float. In the latter case, the turret could remain mobile, pushed along by a water jet.

A rolling radiological nightmare

Of course, the truly wild part of the TV-8 had to do with its insistence on adopting nuclear power for propulsion. On paper, a nuclear reactor has a lot to like in wartime, but the most crucial strategic aspect is how the device effectively never needs refueling. A weapon that could operate on the battlefield virtually indefinitely, unhitched from a diesel-fuel supply chain, would be a revolution in armored cavalry.

Like most nuke-friendly projects of the time, Chrysler decided to keep the atomic aspects of the TV-8 theoretical as well, at least until it had buy-in from the Army and the okay for production. Although the prototype featured the same pair of electric drive motors intended for nuclear-equipped models, it was initially powered by a 300-hp V-8. The engine, configured as a generator, was cribbed from Chrysler’s automotive division (a turbine was also on the drawing board).

Unfortunately, there was a fatal flaw in Chrysler’s nuke-tank plan—one that applied to nearly every similar project of the time. Little if any thought was apparently given to the dangers associated with the TV-8 taking a direct hit from enemy artillery, particularly in its reactor, which lived in the rear, where the armor shape was unlikely to provide enough protection. In the event that an atomic tank exploded, the vehicle would at the very least shower the immediate area with highly radioactive fuel and debris, potentially contaminating nearby soldiers and equipment as well as rendering a significant part of the surrounding land unsafe for hundreds or even thousands of years.

Finally, there was the complicated question of what to do with a battle-damaged nuclear tank: take it back to the depot, where it had the potential to irradiate soldiers and mechanics? Abandon it in the field and simply take the loss?

Multiply either of these questions by the number of tanks in a wartime or even peacetime army (and their respective maintenance needs), and the picture grows more than a little foreboding.

The ghosts of the atomic age

Fortunately for the world at large, Chrysler never had to answer the question. In testing, the Army determined that the TV-8 didn’t offer performance or strategic potential above what was already in the arsenal, nuclear range notwithstanding. Two years after that first prototype was built, the program was shut down. Chrysler wasn’t out of the tank game—15 years later, it helped develop the M1 Abrams main battle tank, a design still in use—but it was definitely done with trying to stuff atomic energy where it clearly didn’t belong.

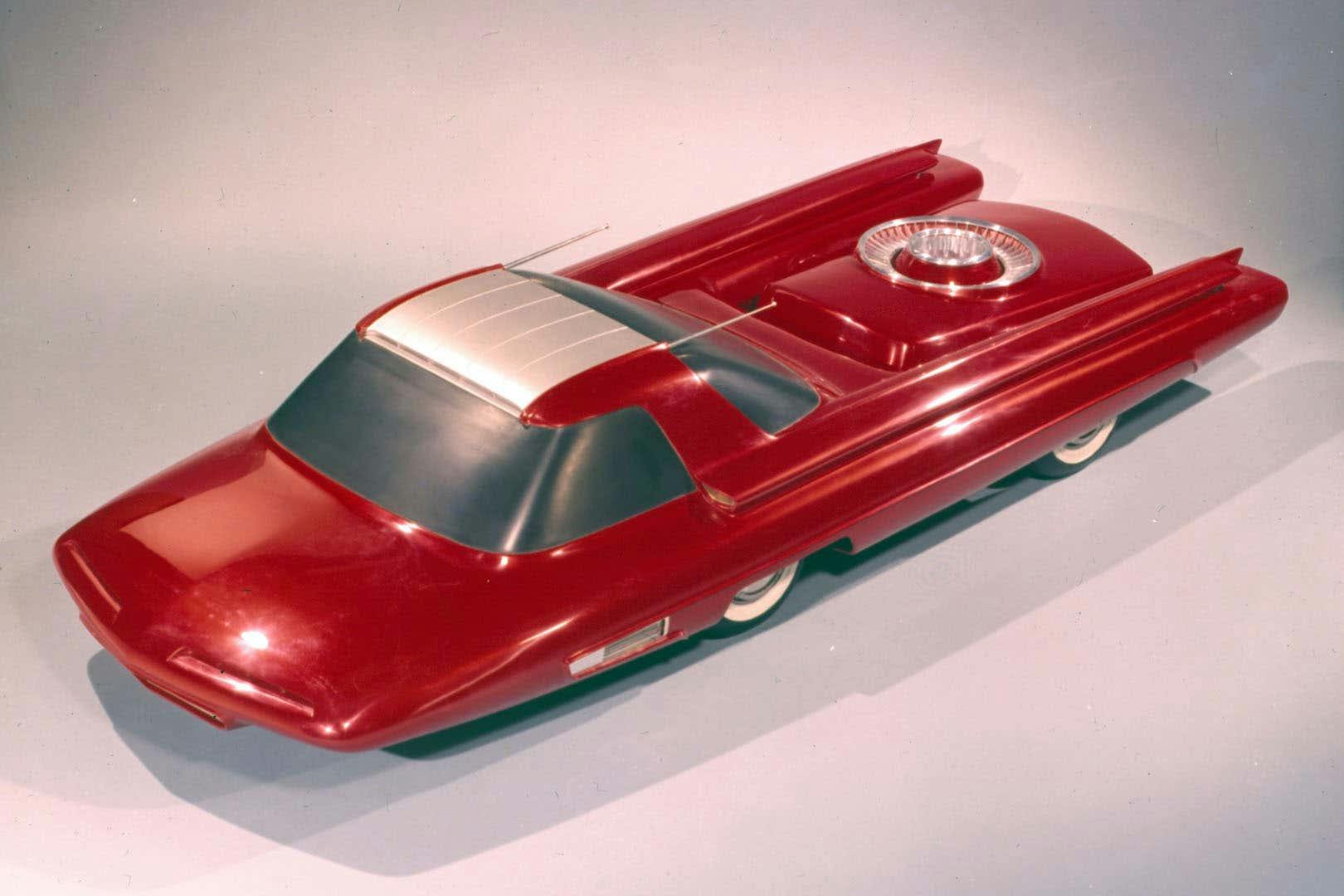

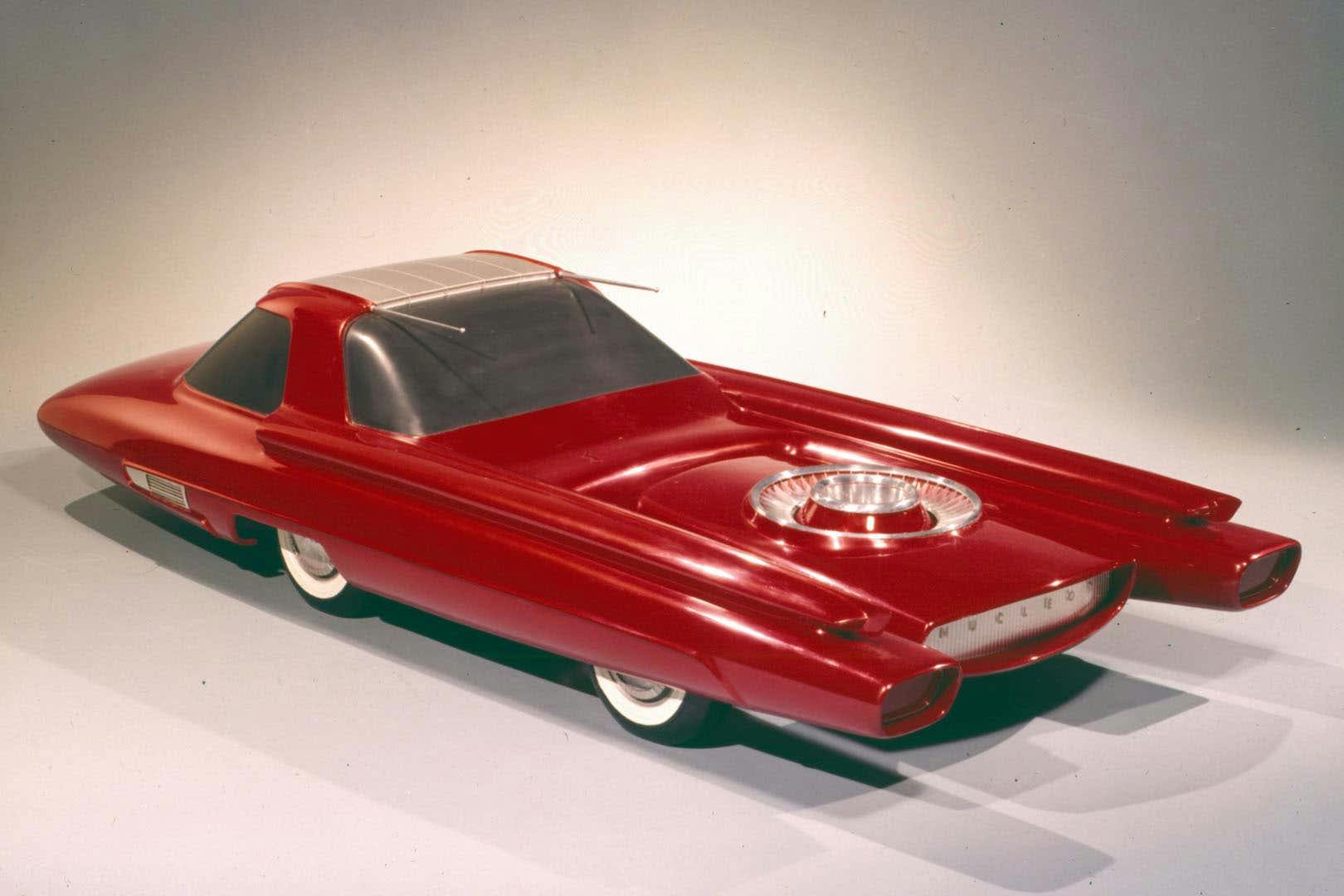

Nor was Chrysler the only automotive titan to push the 1950s atomic agenda. Ford famously produced several scale prototypes of the Nucleon, a show car that linked a nuclear reactor to an electric drivetrain. The company never actually built the reactor, however, realizing that both safety issues and thermal inefficiencies associated with the powertrain’s steam turbine were impractical. Not that this stopped Dearborn from investigating a similar idea with the Seattle-ite XXI of the early 1960s, a concept vehicle that also touted a vaporware nuclear power plant.

By the 1970s, enthusiasm for splitting the atom outside a military context had significantly quieted. The civilian population increasingly focused on the health and environmental fallout from the initial nuclear boom. Having transitioned from whiz-bang technology to malevolent Cold War specter, nuclear power meant ideas like the TV-8 and the Nucleon no longer caught the public’s imagination in the same way. To this day, the dream of a nuclear land vehicle remains unrealized, and as the world increasingly shifts to renewable energy sources, it seems unlikely to ever see reality.