Media | Articles

50 years later, the original JDM sports car remains desirable and boasts a strong enthusiast following

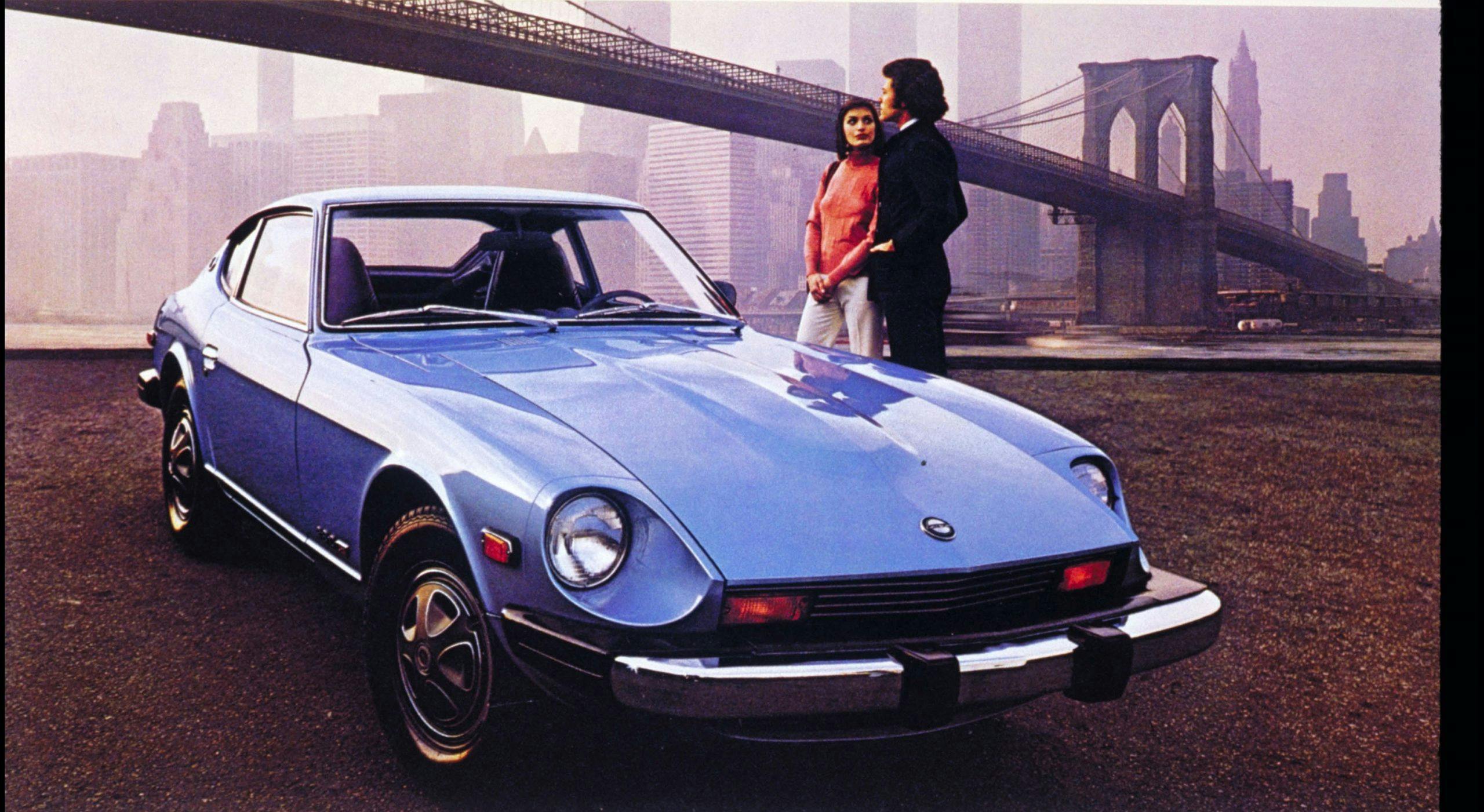

They say time flies when you’re having fun, but how on earth is Nissan’s original Z car turning 50 this year? The sports car that put an MGB-GT and Jaguar E-Type to shame and put Japan on the map with the world’s car enthusiasts could almost pass for something half that age, yet here it is celebrating its golden anniversary. And it is more desirable than ever.

The 240Z had a lot of things going for it when it was introduced to the world 50 years ago. It went on to strike gold for Datsun, despite the number of barriers it had to cross—or get around—in order to generate the kind of sales its Japanese creators envisioned.

Certainly, in America, thanks to Yutaka Katayama, then President of Nissan-USA, the strong sales forecast was spot-on. Numbers remained high for nearly two years after the car’s launch, with waiting lists present throughout the country.

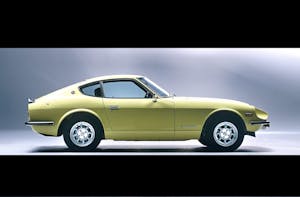

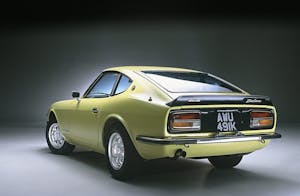

What was not to like about this sporty, beefy little two-seater? For one thing, its design was sleek with a very edgy fastback roofline. Performance came from a well-proven, 2.4-liter straight-six engine that was virtually indestructible, coupled to a highly reliable four-speed transmission. The car’s handling—with a little tail-wagging thrown in for good measure—was superb and build quality was impressive. The name chosen for America, 240Z, was much more acceptable than “Fairlady,” favored in the Japanese homeland, and Z-mania painted much of the American landscape for the first part of the 1970s.

Of course, the barricades to its success were significant, as not many Japanese sports cars existed in the U.S. at the time. Japanese imports were primarily confined to econoboxes—four-door, high-mileage compacts that were easy on the wallet but a little hard on the eyes. Nissan, then known as Datsun, nevertheless wanted to serve as many market categories as it could and had previously introduced a sprightly little ragtop called the 1500 Sports (also called Fairlady in Japan), which grew into the 1600 and later the 2000 Sports, a small, lively two-seat convertible that was the manufacturer’s first sporty entry into America.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The second barrier that the company faced in the states was perception. Could a sports car from Japan really do well in the U.S., the land of powerful V-8s and made-in-Detroit mentality? The answer, we now know, was a categorical “yes.” Priced smartly, thanks to Katayama (known as “Mr. K”), who understood what the American buyer could logically afford, the 240Z had a sticker that was acceptable—lower than a Corvette’s but just a smidge ($200) above that of an MGB-GT, a car that Datsun felt was a logical competitor.

Japanese executives’ third concern revolved around the age of their U.S. audience. In 1970, would a young person want to buy this car? Was there a purpose for its existence among contemporary youth raised on hot rods and drag racing?

Again, the answer was “oh yeah, man.” If there was one thing America’s youth offered—and, indeed, young people around the world—it was buying power, which was unmatched by any previous generation. The 1960s had changed the way people thought. Britain could take credit for much of it, with the incredible cultural change brought on by the Beatles (which ushered in the British invasion of rock ’n’ roll) plus the ascension of the counterculture and the market strength of the younger generation. Soldiers coming back from Vietnam found the 240Z spoke to them and helped them define their independence. They didn’t want to drive their dad’s hand-me-down Buick; they had enough money to afford this little two-door hardtop from their local Datsun dealer and they wanted the freedom to express themselves.

The Z became known as the car with “a Jag hood and Porsche performance” for far less “bread” (or pounds or yen) than anything else on the market. And while its competitors—sadly, a group that included many British makes—languished in their respective showrooms, the Z sailed out of lots. Total sales weren’t comparable to the Ford Mustang’s, but for a brand-new Japanese import, The Z put up staggering stats.

Which brings us to the second half of this story—the UK market. Datsun/Nissan had a much slower start in Britain, which is perplexing; a right-hand-drive market should have made importing the Japanese model far easier.

Yet, British buyers were unaware of the Datsun brand. The Fairlady Roadster—the 240Z’s ragtop predecessor—was never officially sold in Britain. Datsun didn’t even arrive in England until 1968, when it first introduced the 100A (known in Japan as the Cherry) as a two- and four-door saloon, along with a coupe and a small estate (what we Yanks call a van), which was logically badged as “Van.” Keep it simple, right?

Buoyed by its initial success, Datsun dipped its toes further into British waters by bringing in the 240Z. There, as in most English-speaking countries, the letter Z is more commonly pronounced “Zed”; in the U.S., it’s pronounced “Zee.” Calling it a “240 Zed” didn’t seem as appealing, so in many cases, the car was referred to as the 240 Coupé, with the accent clearly marked on the “e.” That may have allowed pronunciation as “cou-pay,” but it didn’t matter.

The problem was that few British buyers could afford the Z, Zed, or Coupé because the car was pricey, thanks to duty (aka “protectionist tariffs” levied against Japanese imports) and added transportation costs. The E-Type, by comparison, carried none of these markups.

Nevertheless, Datsun introduced the Z in October 1970 at the Earls Court Motor Show. While public reaction was encouraging, the car did not become a big seller. According to Richard Heseltine, writing in the May 2007 issue of Motor Sport, “a small if select retinue in Great Britain were attracted to the car, with even the legendary Donald Healey reputedly a fan.”

Over time, the number of Z-cars in the UK have increased and sales of Datsun—now Nissan—products increased as the years progressed.

Some media and enthusiasts will say that the Z was timed right for the world when it launched in late 1969 through 1970. However, that evaluation depends largely on the country. Competition was keen in the UK, comprised mostly of the MGB, TR6, and the E-Type (within Europe, there was the Opel GT). Some even saw the Z as the modern-day successor to the Healey.

Fortunately, the Z has endured and, like some of Britain’s finest sports coupes—the E-Types and Healeys in particular, which have increased in value over the last several decades—the early 240Z has begun to acquire a certain cachet of its own, which has played into rapidly escalating prices within the market.

Recent activity among several auction houses, including Bring a Trailer, where an original 240Z sold for $310,000 (about £238,000 at the time) has demonstrated that some of the rarer versions—those sold in the UK along with others possessing low VINS and a select number of the 39 vintage Zs that were restored by Nissan in the mid-1990s and then sold to the public—are fetching high prices. It’s about time.

As the Z turns 50, it is finally getting its deserved recognition. Those who are fortunate enough to find themselves in possession of one, be it an early model or a contemporary offering, will know that their machine joins a proud lineage, one that should continue to be respected for years to come. The 240Z proved a shrewd investment for Datsun, pleased hundreds of thousands of enthusiasts, and changed the way the world viewed Japan’s car industry.

Pete Evanow is the author of Z: 50 Years of Exhilarating Performance, published by Motorbooks International. Click here to view on Amazon. He has worked extensively in motor sport, including the IndyCar series, and ran Nissan’s Z Store, overseeing the restoration of 240Zs for Nissan in America.

Via Hagerty UK