Media | Articles

Our tame fighter pilot wonders: Should this Jeepster be sent to the boneyard?

The first time I ever fired a missile from a moving plane was against an F-4 Phantom target drone. It was glorious and I walked around the house for a week making “Whoosh!” sounds, disregarding the giggles from my wife and kids as I did so (I’m unsure if they were laughing at my poor attempt at sound effects or the stupid grin on my face resembling that on a toddler racing down the hall double fisting stolen chocolate chip cookies while being chased by a parent). The F-4 was well beyond visual range, and although I was going, approximately, Mach snot when I pushed the “pickle button” to shoot it, the missile was instantly gone. As it roared away—adrenaline rush notwithstanding—I couldn’t dwell on the awesomeness of what had just happened and I tactically maneuvered my aircraft exactly as I would have had I taken a shot at an actual enemy aircraft. As opposing fighter aircraft fly towards each other, their closing velocities easily exceed 1000 mph, meaning that even delaying my maneuver by the amount of time it takes to say “Whoosh!” is a bad idea.

There are a long list of factors that need to be met before pickling off a missile, not the least of which are ensuring you’re shooting at an enemy aircraft and that the target is in range of your missile. Once you’ve assessed all relevant factors are met, you push the pickle button and whoosh!, the missile is gone.

Presuming they aren’t shot down or crashed, aircraft go to “boneyards” to die. The only boneyard in the United States for military aircraft is located at the Aircraft Maintenance and Regeneration Center (AMARC) near Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, AZ. Spanning 2600 acres of the Sonoran desert in the southeast corner of Tucson, the boneyard held more than 6000 aircraft at the end of the Vietnam conflict and holds something like 4400 now.

The whole boneyarding process is a little strange. Someone—usually Congress or a branch of the military—decides it’s time for a specific aircraft or entire series of aircraft (all F-14 Tomcats, for example) to retire, and the aircraft is/are flown to Davis-Monthan. (Tangential trivia question: They aren’t all retired, so what country is still flying F-14s?) I have not dropped off an aircraft there, but I have friends that have done it. The pilot lands, taxies to the designated area of the airfield and parks. By the time he/she shuts down and climbs out, ground personnel have started processing the aircraft (draining fluids, applying protective coverings, etc.) for either long-term return-to-flyable-state storage, removal of parts (you think only classic car owners have parts vehicles?), or scrapping. A jet that a few minutes prior was fully combat capable is then towed off into the desert and parked next to others like it to await its fate.

One cool thing AMARC does is prepare some aircraft for conversion into aerial targets—full-size drones flown from a ground station that are used in weapons testing and target practice. Whereas the target the day of my first missile shot was a venerable F-4 Phantom, that inventory has been used up and F-16 Vipers (nee Fighting Falcon) are now the full-scale aerial target du jour.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Side note: to me, the saddest moment in the history of parking flyable aircraft occurred on October 14, 1997, when President Bill Clinton used a line-item budget veto to park the remaining SR-71 Blackbird aircraft, an aircraft I’ve loved ever since I saw the G.I. Joe version in 1986. Its pilots were literal card carrying members of the Mach 3 club, and the Blackbird is perhaps best known for its speed runs—London to N.Y. in less than two hours; 68 minutes, 17 seconds to fly across the U.S.A. It still holds the absolute speed record at 2193.2 mph and the record for sustained altitude in horizontal flight at 85,069 feet, a height greater than a stack of 19,260 of John Cooper’s original Minis—provided the cone and trumpet suspension isn’t sagging. The Blackbird’s pilots wore spacesuits and ate food through a straw squeezed from a toothpaste tube; the air friction at Mach 3 was so high that they would hold the tubes of food against the windscreen to heat the contents prior to consuming them (nobody wants to eat a cold “smoothie” made from roast beef with mashed potatoes and gravy!). If you ever meet an SR-71 pilot, ask them about: unstarts, seeing the sun rise and set multiple times on the same sortie, Triethylborane, and how it took two 401 cubic-inch Buick V-8s with straight pipes to start each of the SR-71’s two J58 engines on the ground (700 to 725 ft-lbs of torque was the sweet spot during start); you won’t regret it. Amazingly enough, the J58s were most fuel efficient at Mach 3.2 and the oil used to lubricate them was so thick it had to be preheated to a minimum of 158° Fahrenheit before the engines could be started, as its ambient-temperature sludgy viscosity would otherwise preclude engine rotation.

Congress doesn’t get to send cars to the boneyard, “Cash For Clunkers” aside; the decision of when to sell or retire (the word junk sounds so harsh) a car can be a tough one. My mom has cried as she and my dad traded in beloved vehicles, though her tears were quickly dried in one instance by the wind whipping through the windows of her new Mini Cooper S. I’ve written fondly of our 2006 Honda Odyssey and our intent to keep it until it dies. Unlike aircraft, which fly until the government decides they don’t any longer, we’ll use the Odyssey up until there’s no life left in it.

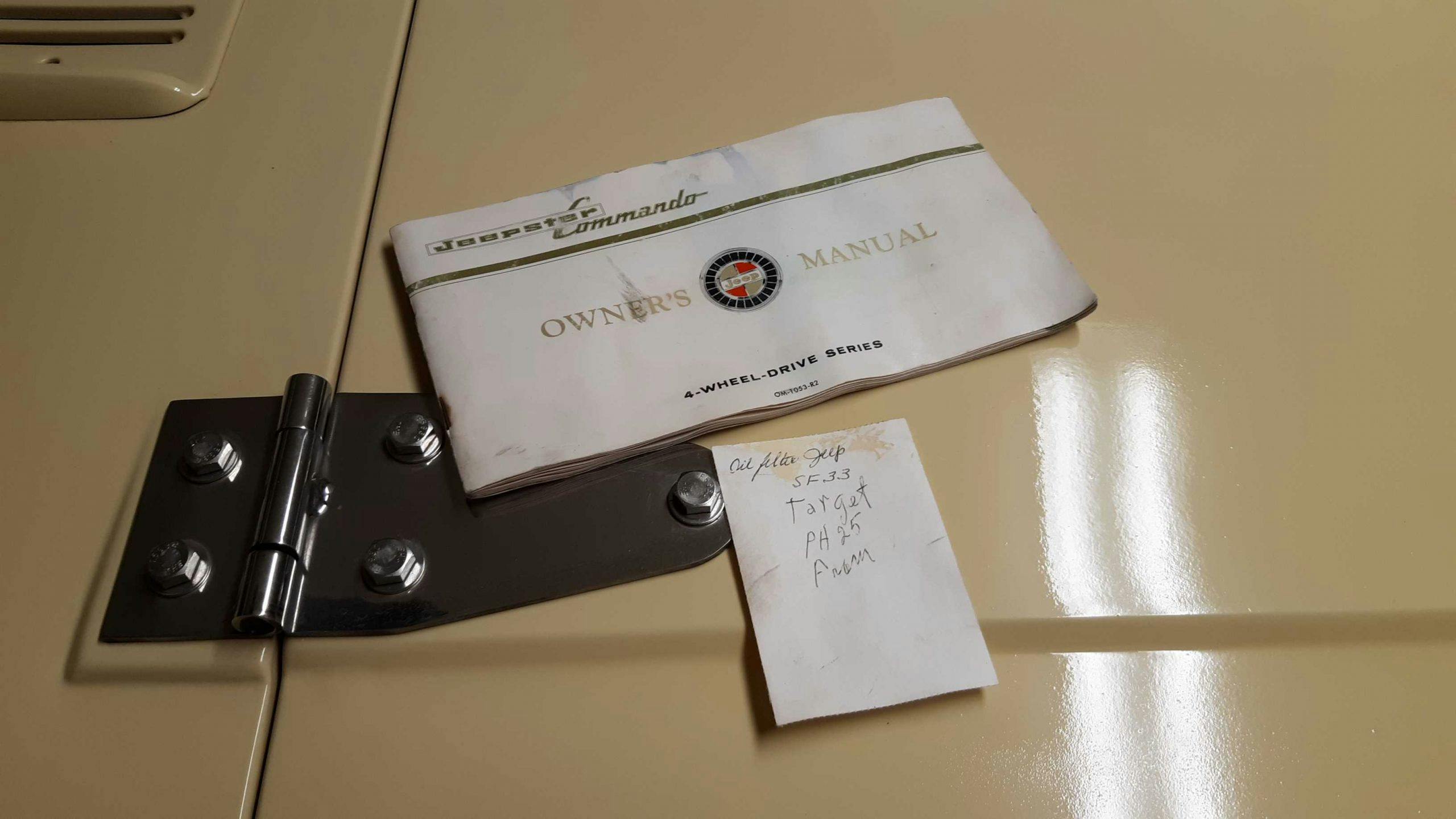

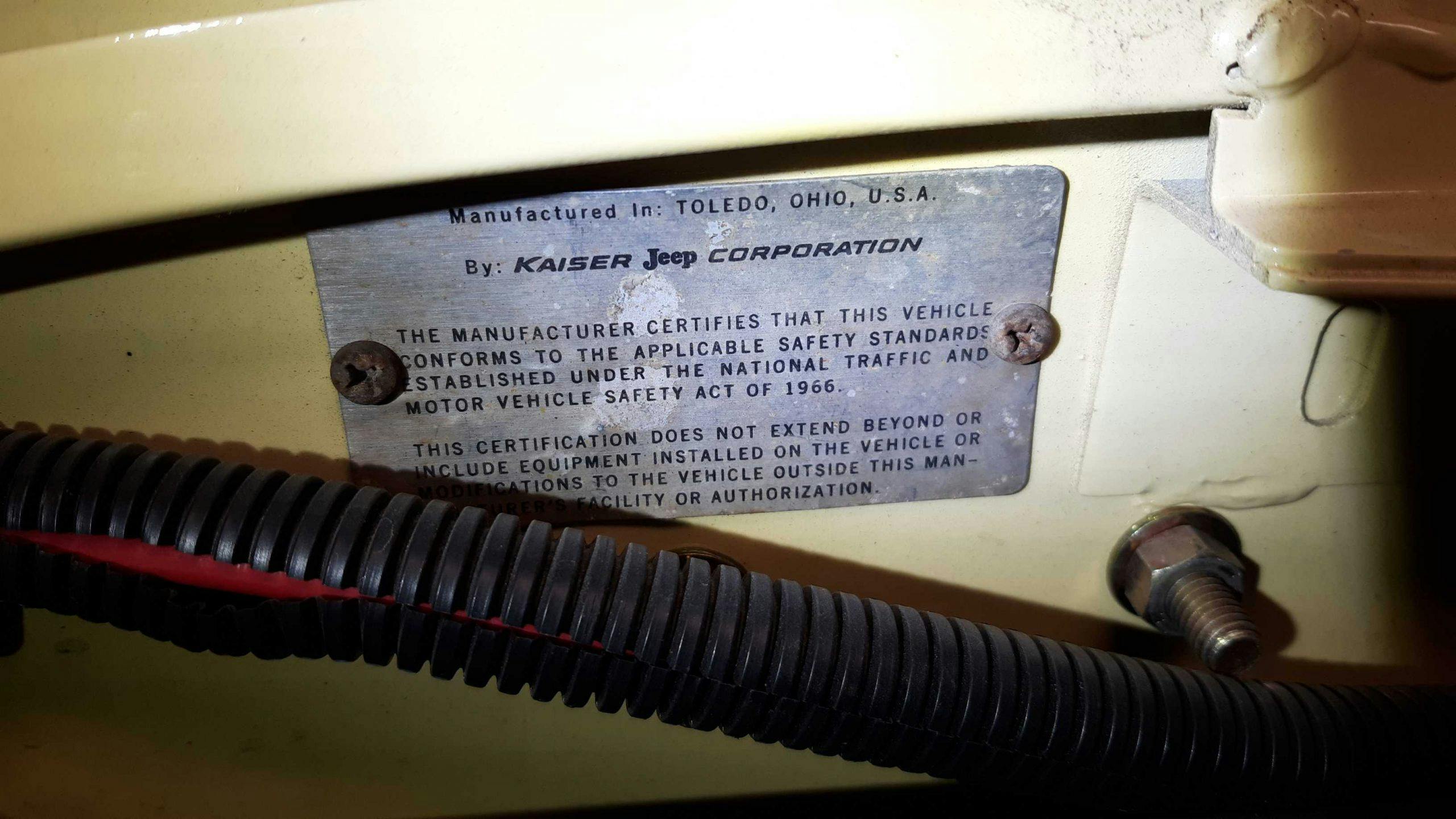

Which brings me to our 1969 Jeepster Commando. While the Jeep’s Buick Dauntless odd-fire V-6 powerplant isn’t the most fuel efficient—I estimate it gets about 10 mpg—it’s still way better than the approximately 40,000 pounds (~6000 gallons) of fuel per hour the J58s burned. The question here isn’t fuel efficiency, it’s when to sell a vehicle that’s fully functional, fun to drive, and paid for. When is the right time to let it go down the road driven by a new owner or off to an automotive boneyard to become scrap metal or parts? The question is even more difficult when there are deep emotional ties to the vehicle as in the case here. Clearly, I have no plans to scrap the Jeepster, but after nearly 47 years in our family, it might be time to let another family enjoy it as much as we have.

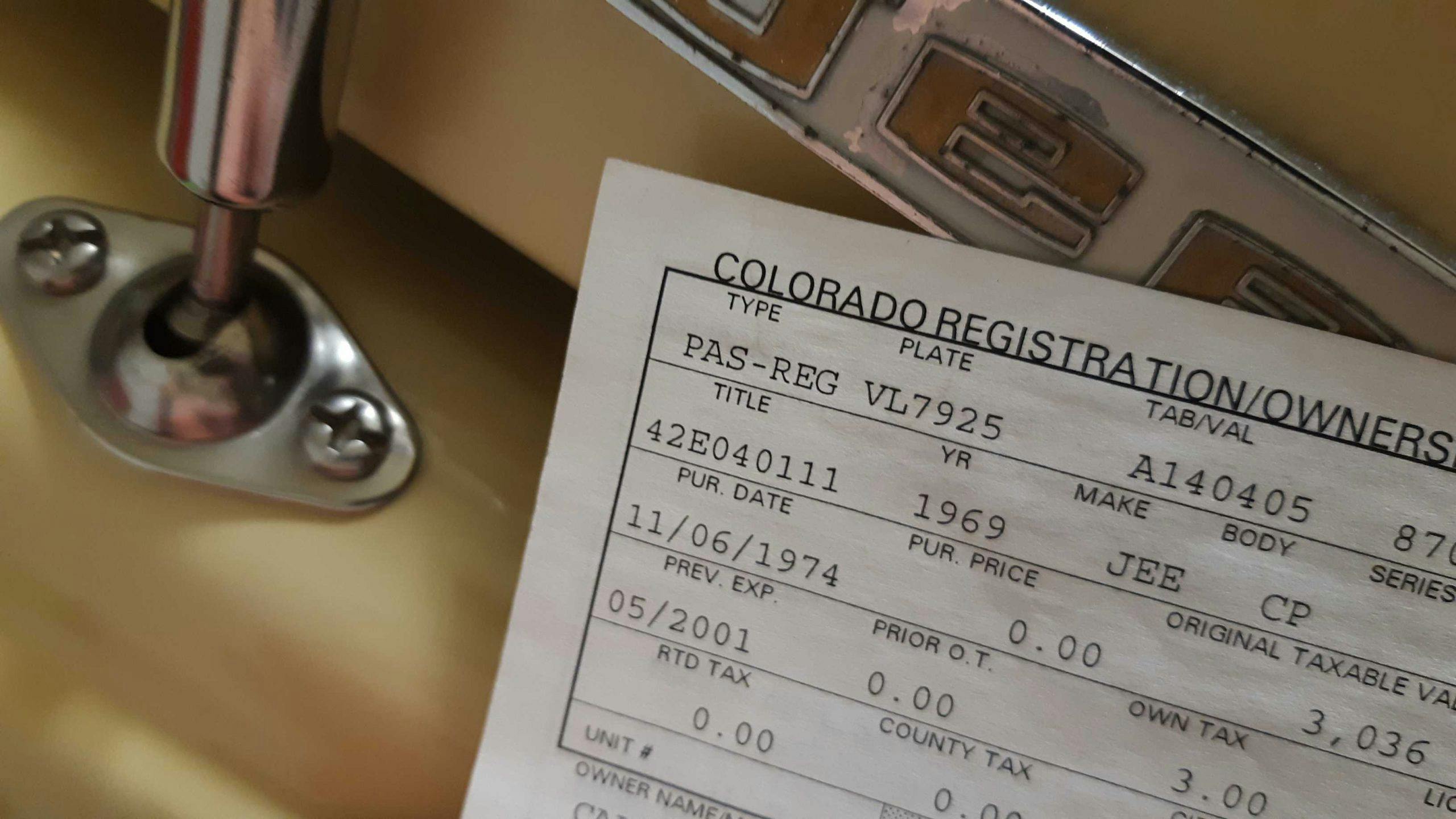

I had long thought that my grandfather purchased his yellow 1969 Jeepster Commando (C-101) in 1973. However, in digging through some papers I found a 20 year-old Colorado registration that showed he purchased it on November 6, 1974 and the original taxable value was $3036. Its 12-digit VIN explodes most online decoders’ brains. Luckily, there is one on the Jeepster Commando Club website that tells me, among other things, it’s a station wagon (ouch!) with a smogged 225 cubic-inch V-6.

Growing up, as we’d take summer trips to visit my grandparents and enjoy Colorado’s natural wonders, I spent plenty of time riding in the yellow Jeepster and thinking it was the coolest car ever. When my parents were relatively newly married, they took a break from grad school one year and road-tripped to Colorado, during which they went for a ride in the Jeepster. Unbeknownst to them, the hood latches weren’t latched. As they sped up, they were shocked when Bernoulli took over, causing the hood to fly off the Jeepster and skid to a stop on the road behind them. My grandfather installed a bonus hood ornament (it’s still on there!) and used it to pull the dents out of the hood. When I had the Jeepster repainted in 2012 as part of my frame-off restoration, there were still scratches in the hood’s paint from my parents’ joy ride nearly 40 years earlier.

In the early 2000s, my uncle purchased the Jeepster from his dad and daily drove it for years. During one of our many military moves, we spent a night with my aunt and uncle and admired the Jeepster. I commented if he ever wanted to sell it he should call me; I bought it in 2007 for $2400.

Not wanting to make this a build thread, suffice it to say that I initially did, or had done, a bunch to it in order to get it to a good state (rebuilt carb, fixed up the drum brakes, put a Dana 44 axle on the rear, new clutch, flywheel resurfaced, new starter, etc.). After six months of driving it, we moved to Germany and then Korea, and the Jeepster spent three years at my parents’ house where they drove it on occasion—always checking the hood latches first!

In the fall of 2011, I decided to embark on a frame-off rebuild. I told my wife she’d have her spot in the garage back by summer. I wasn’t entirely wrong as she had it back by summer 2013, not summer 2012 as she had originally inferred. Don’t take this as me saying she was unsupportive of the build as she was all-in and helped a ton. She became proficient at working the cherry picker as I installed and removed the motor several times during the rebuild.

During the rebuild, I found a wrench attached to a nut under the dash that had my grandfather’s name engraved in it in his shaky handwriting. When complete, I honored his memory by getting a custom license plate with his nickname.

I’m embarrassed to say how much money I have in it, not to mention the untold hours of work. A favorite photo of one of my daughters has the two of us standing next to the Jeepster showing our dirty hands to the camera, the safety glasses she’s wearing sit low on her nose as they are for too big for her. When the engine was rebuilt, I took the old hydraulic valve lifters, timing chain, and crankshaft bearings to make a father/daughter pair standing side-by-side, as well as a spot to mount the aforementioned photo.

Like any classic car rebuild it’s been a gradual work in progress, but it’s in a good spot now. I enjoy driving it and can easily tell how much better it rides, drives, steers, and brakes compared to how it did in 2007. My wife doesn’t drive it much as it’s a little too squirrely for her, but she and the kids love riding in it. I put in four-wheel disc brakes, power steering, and a roll cage built by a guy that builds race cars to provide some semblance of safety features. Favorite stock safety feature? Easy, it’s the “crash pad” on the dash; apparently, the 52 year-old, one-inch thick foam pad will protect you in case of a crash. Naturally, prior to their nugget bouncing off of the crash pad the driver has to crush the steering wheel with their chest, but we won’t talk about that. My safety brief to non-family passengers consists of me telling them that we’re all dead if we get in any kind of accident. Nobody has ever turned down a ride. (It does have seatbelts, they are just the two-point variety.)

I can pick out every flaw and mistake I made during the rebuild, but have mostly stopped nitpicking and just enjoy driving it.

So why sell it, or even consider selling it? It’s not a money-based decision. We’ve been frugal with our money over the years and insurance is cheap (insert shameless Hagerty plug here!). I’ve had plenty of friends tell me not to sell it and that I would regret it forever if I did. Regret feels like a strong word. I don’t regret the time, effort, money, and bloody knuckles I’ve invested in it thus far and I love the connection to my grandfather I feel when I work on it or drive it (he passed away in 2006). I don’t know, it just feels like it’s time to move on. I’m honestly not sure I’ll actually end up selling it as I’ve gone back and forth a few times over the years. In part, I think, it’s just looking at our fleet of cars (1969 Jeepster Commando, 2006 Honda Odyssey, 2006 Lexus LX470, 2016 Mazda6, 2016 Mazda Miata) and thinking if we were to get rid of one of them, it would really come down to a choice between the Miata and the Jeepster. Do we really need two frivolous cars? Frankly, faced with that (self-inflicted) choice, my wife and I would both choose keeping the Miata—don’t judge me, the Miata really is phenomenal!

I’ve discussed why we’re keeping the Odyssey in another article, and keeping a sedan like the Mazda6 just makes sense when we need something larger than the Miata/Jeepster but not quite the van. The Lexus was just purchased as we love hiking/backpacking/camping and there are trails that the rest of our fleet can’t get to, although we’ve proved the van has pretty good off-road capabilities in the past. That leaves the Jeepster standing in our car version of musical chairs. At some point, does practicality and pragmatism win out over saudade and sentimentality? And if so, when?

Clearly, there’s no formulaic answer to a highly personal question. Frankly, there are times when choices like these have to be made for financial reasons. Other times, well, when you know, you know; you know?

In beyond visual range aerial combat, timelines and threats drive tactics and maneuvers; if this, then this—or die. That said, there are plenty of moments that don’t nicely fit into predetermined scenarios. In those instances, you fall back on your training, work within the prescribed rules of engagement, and, sometimes, listen to the hairs on the back of your neck and do what you think is best. Decide, pickle, whoosh—and it’s gone.

***

For more of fighter-pilot Josh Arakes’ stories, click here.