Media | Articles

If you want to buy Packard, ask the man who owns it

No, that’s not a typo, it’s Packard that’s for sale, not “a Packard.”

Did you know that there are holding companies that specialize in reviving what are known as “distressed brands,” which is to say, brand names that due to either corporate error or neglect are no longer top-shelf goods? That’s because brand equity lasts forever. There are hundreds of millions of people born after 1966, when the nameplate was last attached to newly assembled automobiles (in either Canada or Israel, it’s a complicated story), who recognize the name Studebaker. Likewise, although the Beatles’ hairstyles may have made men’s hair products uncool for half a century, plenty of baby boomers remember Brylcreem and its slogan, “A little dab’ll do ya!” People also still remember the humorous Burma Shave roadside signs, which may mean there’s an opportunity to be had; that brand’s longtime competitor, Barbasol, has been rejuvenated and is now a market leader.

You might ask, if Studebaker still has brand equity, why has nobody ever tried to revive that brand? Well, to begin with, having a cosmetics manufacturer package a legacy recipe under contract isn’t quite the same as investing a billion dollars in a new mass-market automotive platform, plus another billion or so if that new platform is going to have a new engine to go with it. The risk is much higher.

Come to think of it, has anyone ever successfully revived a car brand? Lots of people have floated the idea. But BMW’s buyout of Mini seems to be the only that comes easily to mind. Actually, that may not really count, as there was only a brief hiatus between the end of production for Alec Issogonis’ Mini in 2000 and BMW’s from-scratch take on the brand the following year.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

We recently looked at the 1956 Packard Predictor, the last concept car Packard ever made. Although it didn’t save Packard, it did portend many automotive styling trends of the 1960s. Studebaker tried to save itself by merging with Packard, but the automakers’ combined red ink gave them an even lower chance of succeeding against the Big 3. Studebaker made a half-hearted effort with some very peculiar looking “Packardbakers” and then just killed the brand. While the Packard enthusiast community has been fairly active and strong since the company’s demise, there was less interest from corporate America in reviving the brand, which has since passed into the public domain.

In the late 1970s, Lima, Ohio-based customizer and coachbuilder Budd Bayliff reregistered the Packard trademark and started using it for Buick Rivieras, Mercury Cougars, Ford Crown Victorias, and even some hearses that he graced with an approximation of Packard’s signature “tombstone” or “horse-collar” grille.

After some years, a Canadian by the name of Roy Gullickson enters the scene. A former farmer and pilot who had worked as an engineer for truck maker White Motor Car and tractor maker Massey-Ferguson, Gullickson co-founded a farm equipment company in Alberta called Keho Products and made it successful enough that he sold his share in it for $2 million in 1992.

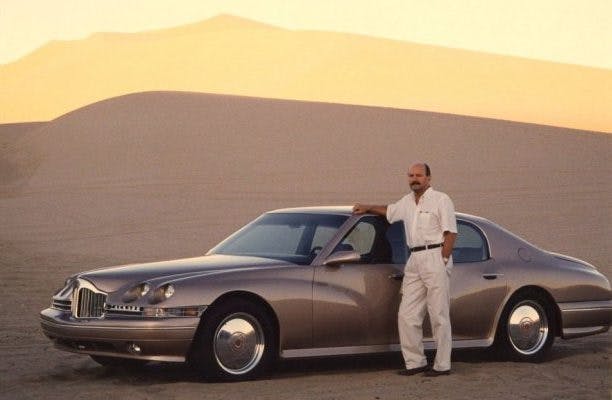

That same year, Gullickson purchased the rights to the Packard brand from Packard Bayliff Coach for $50,000. He would go on to spend many times that amount trying to revive the brand. Unlike many automotive startups, whose proposed vehicles have existed only on paper or in pixels, Gullickson seems to have gone about renewing Packard in the correct way, with an actual car. He started with a fully functional prototype he could show to investors, potential dealers, and customers.

After buying the rights, Gullickson incorporated the Packard Motor Car Company in Arizona, saying that he wanted to build “ultra-luxury, high-performance full-size American automobiles.” Thus began the dream of the Packard Twelve.

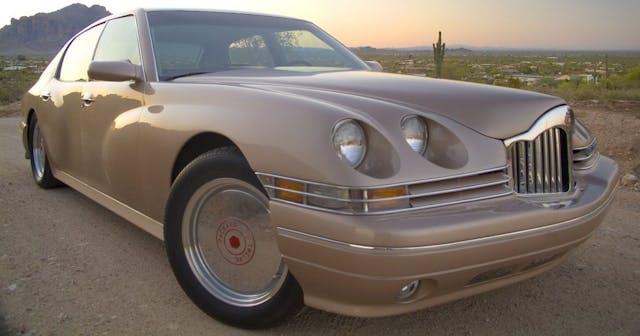

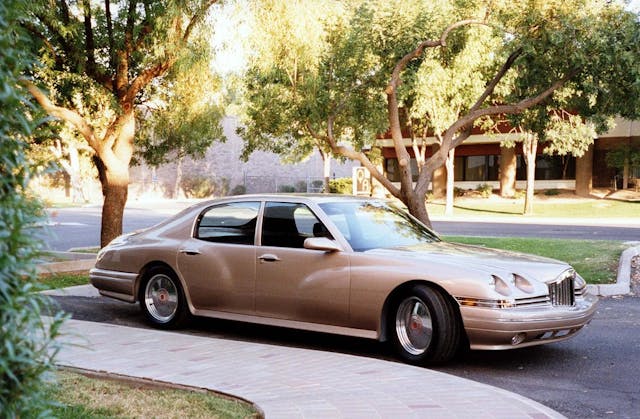

Gullickson hired designers Arunas Oslapus and Don Johnson, late of the neoclassic Zimmer Quicksilver, to style an all-new four-door aluminum body harkening back to the 1941 Packard Clipper. By 1996 they had produced a full-sized model. Gullickson and former Packard engineer Lawrence Johnson, working with another four engineers and technicians, developed a 119-inch wheelbase aluminum spaceframe chassis that used state-of-the-art high-strength aluminum extrusions. Suspension parts were also made from aluminum and tested with dye penetrant and X-rays to ensure strength. Disc brakes at each corner featured relatively large 13.2 inch rotors.

Power was supplied by a 525-cubic-inch, all-aluminum V-12 from Falconer Racing Engines, using mostly GM engine management systems, that produced either 440 or 573 horsepower, depending on the source quoted. The engine was backed by a GM 4L80E four-speed automatic, and full-time all-wheel drive was effected by a Borg-Warner transfer case with a viscous clutch and a 65/35 rear/front torque split.

The one-off 1999 Packard Twelve prototype is a large car, but due to all of that aluminum it weighs just 3750 pounds, which explains the claimed 0-60 mph time of just 4.8 seconds and an ability to do the quarter mile in 12.5 seconds.

In their day, Packards were America’s leading luxury car, and Gullickson had his 12 prototype fitted appropriately, with a full-leather interior, hand-finished walnut veneers and trim, power seats, windows and locks, along with climate control, fully functional modern instrumentation (with a 1930s aesthetic look) and an AM/FM radio with a CD player and changer.

The prototype was completed in 1998. Original reports said that the concept vehicle cost Gullickson $800,000 to build though he later revised that figure to $1.5 million. Hemmings quotes him as saying, “and that doesn’t include my time.”

Unfortunately, Gullickson may have turned off some of the brand’s most enthusiastic fans by sending out cease-and-desist letters to Packard club members selling merchandise with the Packard logo. Also, as impressive as the Packard Twelve prototype is from an engineering standpoint (certainly up to historic Packard standards) it could not be considered widely attractive. Trying to evoke the 1940s Clipper makes it look a bit dumpy awkward. To be frank, Dick Teague did a much better job evoking the traditional Packard grille in the Predictor than Gullickson’s team did with the Twelve. Of course that’s a matter of taste, and your tastes may differ from mine.

Still, the business plan seems to have been sound. According to an article in the February 2000 edition of Forbes, Gullickson’s plans included raising $30 million within three years so he could start producing as many as two thousand $160,000 ($248,000 in 2020 dollars) Packards a year by 2010.

Gullickson showed the Twelve extensively in 1999, at car shows and Packard events celebrating the centennial of the company’s founding in 1899 in Warren, Ohio.

In 2000, Gullickson told Forbes that he had orders for 70 cars, but in the end he was never able to raise enough money to start production. “We knew we didn’t have the capital to go into production,” Gullickson later said, but as part of the original business plan, his team had long considered bringing in outside investors or selling the brand outright. By 2007, Gullickson and his wife were at an age when most folks consider retirement. In 2008 he put a $1.5 million price on the entire package, including the one-off Packard Twelve, related engineering materials, and rights to the Packard brand:

“We are interested in selling the company by way of selling all of the issued shares of the company, now held by my wife’s and my holding company, Packard Holdings Inc. Purchase of those shares would give the buyer 100% control of the company, and ownership of all of the assets, consisting of the Packard name trademark for automobiles and parts, the prototype Packard automobile, a certain amount of toolage, and all of the engineering drawings and calculations, suppliers names and contact information, and spare parts. The asking price is $1.5 million, which is significantly below the amount of investment in the project. The company is debt-free and has no legal encumbrances.

We wish to sell because we are both well into retirement age, and would really like to see new Packards in production. That, in fact, was the main impetus for going into the project, and we have always planned on bringing outside capital into the project, or selling to a capable buyer. There is an excellent basis for making a very attractive business case. We are receiving strong interest in the company, but are not committed at this time.”

Gullickson said he had a few tire kickers, but nothing solid ever happened. “We always had a lot of interest, but no combination of interest and capability,” he said.

In 2014, Gullickson and his wife sold the prototype Packard Twelve separately at the RM auction held in conjunction with the Concours of America at St. John’s in Plymouth, Michigan, just outside Detroit. That venue was likely chosen because that concours always brings out a number of classic-era Packards and plenty of Packard fans. The car sold for $143,000, less than ten cents on every dollar it took to build it.

If you have dreams of owning a car company, rights to the Packard Motor Car Company are still for sale. And according to Gullickson, you had better move fast. “We have had serious inquiries and we are currently working on one which we expect to close early next year,” he told us.

The automotive world has seen many new startups in recent years, particularly in the EV segment. When asked what advice he’d give to anyone contemplating starting their own car company, Gullickson had sound guidance. “I would advise them to have a good chunk of funds to begin with and bring in funding partners with good and extensive experience automotive-wise.”

I agree that Gullickson stepped on his John Thomas, by issuing those cease-and-desist orders; instead he maybe should’ve offered to let them use the logo, for a very reasonable fee.

And he should have given them shares in the company for providing advertising services, and enlisted them in fundraising. He should also have designed and promoted a ‘Packard Electric’ car using the same styling or an adaptation thereof.

Actually, the “Packard” name, the Packard coat of arms, and the “Packard” script are registered trademarks of The Packard Club aka Packard Automobile Classics. He never owned them.