Media | Articles

Confessions of a recovering flipper

At some point during the George H.W. Bush administration, I bought a 1972 Porsche 911S for the now absurd-sounding sum of $6500. In the ensuing 30 or so years, I’ve owned roughly 50 vehicles. As Dirty Harry says, “In all this excitement, I’ve kinda lost track myself.” So, even though I don’t consider myself a “flipper”—I simply have a wicked case of automotive ADHD and insufficient storage space—I have in fact completed quite a few flips. Enough to recognize a few basic truisms about the market and myself.

Let’s start by analyzing my disclaimer. Almost no one in our world wants to be labeled outright as a flipper—that is, someone who buys and sells collector cars solely for profit. And, truth be told, very few people are just in it for the money, not even the dealers and auction company pros who do it for a living. For most of us, “profit” is just something to pour into the next car, the one you really want to keep. At least, that’s the theory. If you’re not careful, that very motivation can have a deleterious effect on enjoyment of the hobby … but more on that later.

As much as no one wants to be a flipper, almost everyone wants to talk about their flips. At least, the good ones. It’s human nature to remember the wins and gloss over the losses. To hear most tell it, they align more with the crack paratrooper from Band of Brothers, who single-handedly charged a machine gun nest on D-Day, than the 4F black market profiteer.

The locker room talk around flipping often consists of rank over-simplification. IE: “I paid $6000 for that 944 on Facebook Marketplace and sold it for $12,000 on Bring a Trailer. Ain’t life grand?” A majority of us do little to no accounting for the 6.6 percent in taxes paid, registration fees, insurance costs, timing belt and water pump done in preparation for sale, (because that’s the kind of seller you are) or the ultimate in cost estimations: the value of your time.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Hand in hand with the underestimation of one’s costs goes the overestimation of one’s cleverness. Most successful flips come down to something else entirely—luck. Specifically, the fortune of buying the right thing at the right time.

Yet knowing a thing or two about what you’re buying can help. More pointedly, not knowing can really hurt. Take my brief, bruising ownership of a 1963 Buick Riviera. I always thought they were nice cars to look at. I could have kept looking, free of charge. Instead, I bought one and soon found out they’re nothing like what I’m used to driving, with pinky-light, utterly numb power-steering and tiny drum brakes that provided largely theoretical stopping power.

No biggie, I thought, I’ll just flip it. I had purchased the car out of an estate sale for what I thought was a well below market price, and it a two-owner car with original paint and zero rust. A base 911T in that shape would sell for a significant profit.

As it turned out, Rivieras are not 911Ts. Buyers of first-gen Rivs favor GS-spec cars with fresh, shiny paint. In other words, the market had zero interest in a preservation-class base Riviera. I spent thousands of dollars toting it from auction to auction only to sell it at a loss. I made the fatal mistake of buying a car I knew nothing about.

If people have a tendency to overemphasize the upside on flips, they get downright libelous when it comes to making money on restorations. As restoration costs have spiraled in the last 20 years, even the pros have seen their margins shrink to “not worth it.” For an enthusiast hoping to put a little life back in a car and make a profit on the other end, it’s easy to get underwater fast.

About 14 years ago, I bought a sound, but slightly tatty 1967 Maserati Mistral. At the price I paid, it seemed like I was a bit of paint and seat leather away from a six-figure payoff. To maximize my chances, I did the work myself—from the paint and interior to sorting the notoriously finicky Lucas fuel injection. When finished, I toyed with keeping the car, but I already had a Series I E-type coupe that did everything the Maser did, without the potentially ruinous upkeep costs.

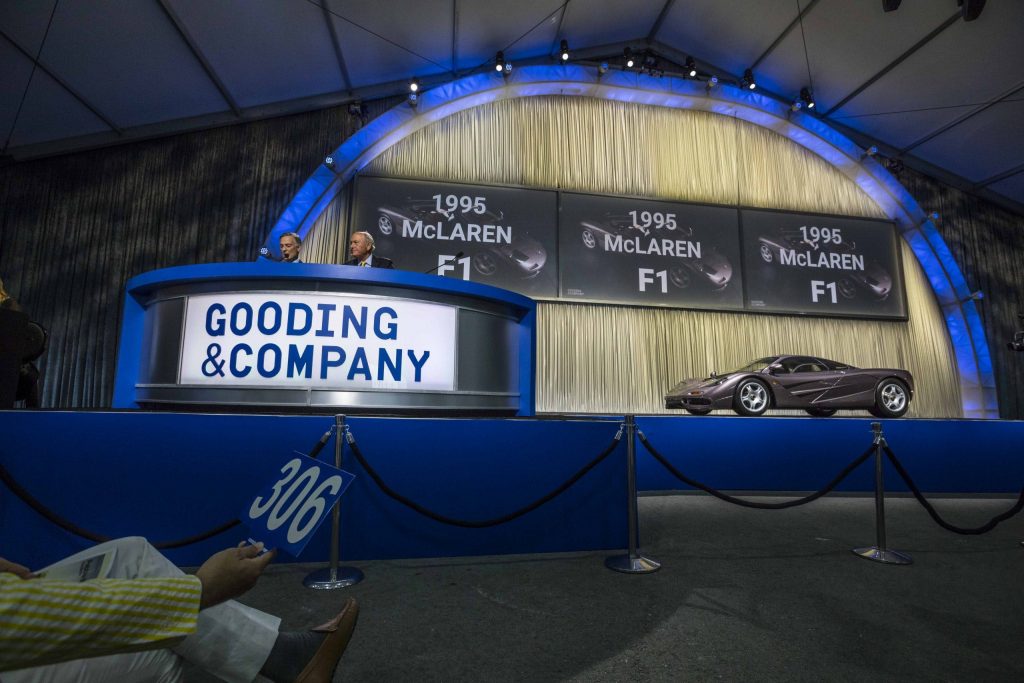

Alas, that whole lucky timing thing can work both ways. As it turned out, I decided to part with the car in 2008, during the worst economic downturn of my lifetime on both the micro (divorce) and macro (global economic crisis) levels. I figured the car’s presentation at a big-name Monterey catalog sale would save me. Flash forward me to excusing myself from the auction tent to get very ill behind a row of porta-Johns after the car hammered at an absurdly low, no-reserve price.

The bulk of the loss was, you guessed it, what I spent “improving” the car. Had I simply done nothing and held it longer, I’d have made out fine. The buyer of my car certainly did. Adding some kind of twisted karmic insult to injury, he turned out to be a flipper himself, shipping the car back to Europe and selling it about a year later for three times what I sold it for. Oh, and before that, it appeared in the James Bond film A Quantum of Solace, a movie whose title I tend to “Freudianly” mangle as, A Quantum of Anguish.

That last loss was probably the thing that brought about a change in my buying and selling habits. A near addiction to making money was truly taking the fun out of the hobby. It became like the bad Western movie cliché, “When you set out for revenge, first, dig two graves.”

Am I now immune to the obvious charms of buy low and sell high? Hell no, I’m as much a capitalist as anyone. It’s just that now, if I make a few bucks, it’s merely a happy byproduct of buying what I like, doing what I enjoy to the car, and occasionally taking advantage of good timing or a buoyant market at sale time. In other words, a successful flip is an exultant ending to a painless transaction.

Rob Sass is the Editor-in-Chief of Porsche Panorama, the official publication of the Porsche Club of America. The opinions stated are his, and not necessarily those of the Club.

Sass, I thought I bought the Riv for you at a WWG auction? Whoever that was, I told them it was a mistake… great article, C