Media | Articles

What story does this 1-of-3 experimental Ferrari engine tell?

You might imagine that the hallowed halls of Maranello contain a perfectly tuned orchestra of designers, engineers, and product planners. Customers are paying top dollar, so creative freedom can flourish and each product launch is perfectly polished. However, Ferrari has dealt with its fair share of thorns in its side, and one particular, experimental twin-turbo V-8 proved the victim of bad timing.

In the early ’80s, Ferrari was busy doing what every company does: trying to make money. Italian road taxes increased exponentially on road cars equipped with engines displacing more than 2.0 liters. A power-dense, low-displacement engine was the practical choice, but, of course, road cars were only half the equation for Ferrari.

At the turn of the decade, Ferrari was scrambling to be competitive with the flock of naturally-aspirated, Ford V-8 entries in Formula 1. In 1979, at the French Grand Prix, Renault’s RS10 had just become the first turbocharged car to win a Grand Prix, and though the technology wasn’t yet wildly popular, it was increasingly viable. Two years later, Ferrari campaigned its first turbocharged car, the 1496-cc V-6-powered 126C. Driven by Gilles Villeneuve and Didier Pironi, the 126C earned Ferrari only fifth in the Constructors’ Championship in 1981, but it helped win the title back-to-back years in 1982 and 1983.

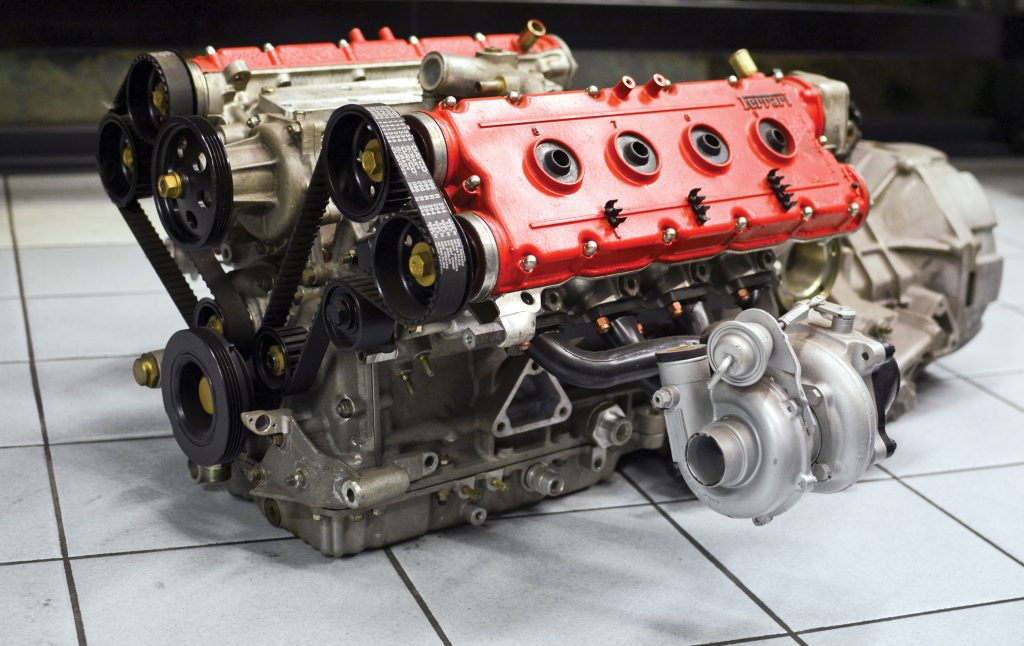

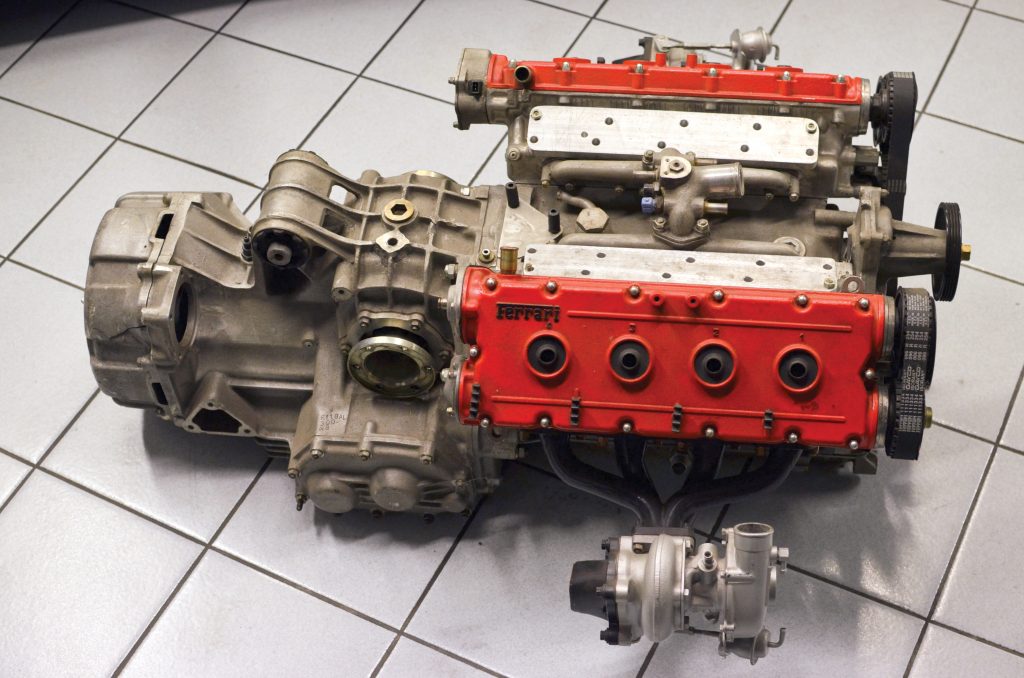

It was only a matter of time before Ferrari’s road cars got their share of the turbocharged fun. At Turin’s 1982 motor show, Ferrari debuted the 208 GTB Turbo, which packed a 1990-cc V-8 with a single turbo. Two years later, the 400-hp, twin-turbo, V-8-powered 288 GTO stormed onto the scene. Our best guess is that, sometime between the production of these two engines, Ferrari built three experimental F121 A engines. One example of these twin-turbo V-8s, s/n 002, is up for sale.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

At this point, we’ve only got scant information from the auction listing regarding this engine’s development history or what Ferrari planned to do with it. For now, then, we’ll seek to provide some historical context and a couple alternative explanations for its genesis.

The first possibility places these engines in “the early 1980s,” per the auction listing (which Race Cars Direct seems to crib from s/n 002’s 2015 sale through RM Sotheby’s). In 1984 Ferrari was still campaigning a 1.5-liter, single-turbo V-6 in F1, so the three F121 A engines could be a riff on that same low-displacement, forced-induction theme. These twin-turbo, 1996-cc engines also slot into a nice, linear progression in Ferrari’s contemporary road cars, slotting in between the single-turbo, 1990-cc V-8 in the 208 GTB and the twin-turbo, 2855-cc V-8 in the 288 GTO. The F121 A prototypes don’t have catalytic converters, but unfortunately, we can’t infer much from that; the U.S. didn’t mandate them until 1990, and even early F40s didn’t have them. It’s more likely these engines were destined for road cars, especially given their 1996-cc displacement, which skims under the 2.0-liter road tax threshold.

Why did these prototypes never reach production, then? Though they boasted an aggressive 77 mm x 53.6 mm bore and stroke paired with a 7.7:1 compression ratio, maybe they suffered from significant turbo lag or didn’t make power at the right rpms. In any case, the 288 GTO’s larger-displacement powerplant suggests Ferrari ditched the idea of a tax special and was content marketing to deeper-pocketed customers who didn’t mind paying the premium for displacement—and thus, power.

Alternatively, you could argue that, since the F40’s engine type is F120 A, these three F121 A engines came far later in the ’80s. If so, these three 400-hp prototypes wouldn’t have challenged the F40’s 480-hp output—which would explain their lonely, chassis-less condition. Additionally, these 2.0-liter units wouldn’t have a logical place in late-’80s racing. The F40 LM went racing with the same 2.9-liter, twin-turbo configuration as its road-going counterpart. In 1989, Ferrari fielded 3.5-liter V-8s in F1, as well as V-10s; and at the 1989 24 Hours of Le Mans, the smallest engine was Porsche’s 3.0-liter turbo. Turbos were officially the theme; but displacement wasn’t as tightly constrained.

Whether either theory is true—and maybe neither is—now’s your chance to grab a slightly mysterious, exclusive slice of Ferrari history.

Any additional insights regarding this exotic engine orphan? Leave a comment to start a discussion in the Hagerty Community forums.