Media | Articles

When four students in two Fords stole the Stone of Destiny

Among the ceremonial objects involved in the coronation of King Charles III, few have a longer tradition of use than the Stone of Scone, also known as the Stone of Destiny.

You may know that the late Queen Elizabeth II sat upon this stone during her own coronation on June 3, 1953, as has every British monarch dating back to the early 1300s. You may not know that, three years earlier, on Christmas Eve, a Ford Anglia idled outside Westminster Abbey. Four shadowy figures carrying a heavy load moved hastily through the night, one badly injured. The morning of Christmas Day, England awoke to find that its Stone of Destiny had been stolen, and that the thieves had got clean away.

The heist transfixed the public for months. Reactions varied: The English were scandalized, but more than a few cheery faces were seen among the Scots. The thieves that stole the Stone of Scone weren’t looking for fame or fortune; they were stealing back a symbol of national pride.

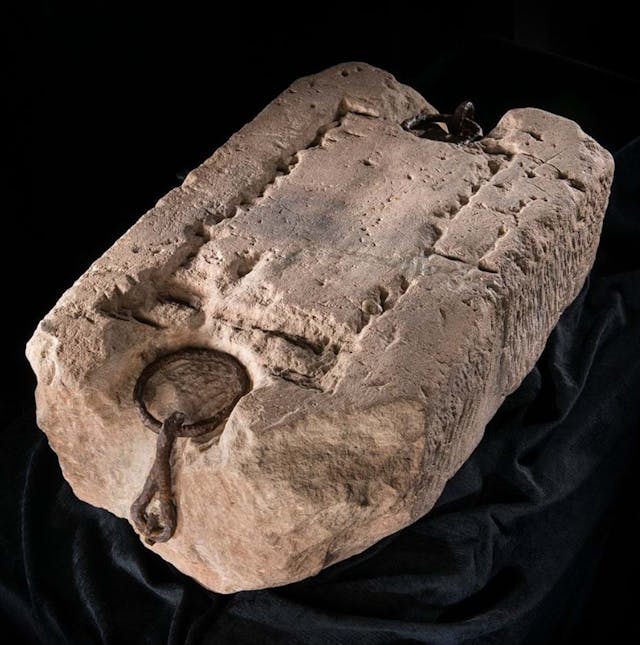

The stone is an unremarkable rectangular block of reddish sandstone, weighing roughly 335 pounds. It has none of the flash or sparkle of the Crown Jewels, but it is equally steeped in history.

Even before December 24, 1950, it was stolen property.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

You may already be familiar with King Edward I, as played by actor Patrick McGoohan in Braveheart. In the film, he’s portrayed as one of the most devious and cunning villains this side of Darth Vader. It’s not an entirely inaccurate portrait, as the real Edward “Longshanks” was uncompromising and ruthless. Then again, few medieval Kings could afford mercy.

Edward I’s other nickname was “The Hammer of the Scots,” which says pretty much everything you need to know about his suppression of the Scottish rebellion. In 1296, having defeated the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar, Edward I looted the Stone of Scone, transporting it to Westminster Abbey as a spoil of war. He instructed a wooden chair be built to house the stone and serve as a throne.

The symbolism is as obvious as that of the fictional Iron Throne made of melted-down swords. (If a bit less spectacular.) The Stone of Scone had been used in the coronations of Scottish kings for hundreds of years before Edward I took it, and various legends suggest it dates to the fifth century. It was, and remains, a symbol of Scottish nationalism.

In 1950, Scottish nationalism had ebbed. Having worked together to defeat the enemy in WWII, the U.K. was a fairly united place. The blue and white of the Scottish flag was part of the Union Jack, and that was that. But in the universities and colleges of Scotland, young people were still interested in their heritage. Four friends at the University of Glasgow met as a result of their shared membership in the Scottish Covenant Association, a political organization created to promote the idea of Scottish home rule. One of them shared a daring idea.

The four were Ian Hamilton, Kay Matheson, Gavin Vernon, and Alan Stuart. Hamilton was a nationalist, but none were true radicals. They were just young. As Hamilton later put it: “I’ve defended a lot of daft people during thirty years as a criminal lawyer, but I doubt very much if I’ve defended anyone who was as daft as we were then.”

Today, a modern car can travel from Glasgow to London in about six or seven hours. In 1950, cars demonstrated more leisurely pace, and there weren’t many motorways, just country roads. A few days before Christmas, the four piled into a couple of Ford Anglias, armed with little more than youthful enthusiasm and a fistful of money from Scottish Covenant Association leader John MacCormick.

A Ford Anglia does not make much of a getaway car. The nameplate gained some unlikely global recognition with the appearance of a fourth-generation model as the flying car in the Harry Potter series, but the cars used in the theft of the Stone were very early models. Their exact model years and configurations are lost to time, but, given a student’s budget, each was likely to a bare-bones saloon, fitted with a three-speed manual and a 933cc engine making scarcely 8 hp.

Add the propensity of the Anglia’s wipers to stop working above 40 mph, and the drive to Westminster Abbey would have provided ample time for second thoughts. Evidently, there were none, or the daring voices prevailed: The four arrived a few days before Christmas and began to scout the location.

It was an amateur job with multiple errors. While skulking about after closing hours, Hamilton was discovered by a security guard. Suspicions were not aroused; the guard assumed Hamilton was down on his luck and gave him some money. On the day of the theft, Stuart and Vernon were discovered in the cloister by the church’s Archdeacon. No one seems to have have been bothered—who would steal a 300-pound rock, no matter how significant?

Because the Abbey had been damaged by bombing in WWII, one of its solid oak doors had been replaced in soft pine. Armed with a prybar, three of the thieves broke in, then set about freeing the stone from its wooden chair. Matheson, the getaway driver, sat outside.

The trio worked feverishly—their mission toed the line of treason. The wood frame splintered. The stone came loose, but its weight surprised them. It crashed to the ground, splitting in two. In the commotion, someone dropped the keys to the other Anglia. Hamilton wrestled the smaller piece—about 90 pounds—out to Matheson in the Anglia and was about to return when a policeman emerged. The pair quickly embraced, pretending to be a couple out on a romantic excursion. The bobby, in a cheery pre-Christmas mood, failed to notice the lump of stone on the Ford’s backseat.

Matheson set off for Scotland. Stuart, Vernon, and Hamilton heaved the remaining section of the Abbey, at which point they discovered that the keys for the second Anglia were missing. Stuart and Vernon escaped on foot. Hamilton rushed inside, found the keys, and ran to the nearby car park. Somehow, he managed to lever the 250-pound stone into the Anglia’s trunk. The car rumbled off, rear springs sagging.

Reuniting with Stuart, Hamilton managed to get his chunk of the stone into a nearby field, where the two buried it. On Boxing Day, December 26, they headed for Scotland.

The public was outraged. Police response was immediate, and their investigation thorough. Witnesses provided a description of the car. Roadblocks surrounded London. The borders to Scotland and Wales closed. Matheson slipped through, a single woman traveling alone being, evidently, suspicion. The other three also escaped—and returned about a week later to recover the larger piece of stone from the field. Once back into Scotland, they baptized their prize with whiskey.

It took until April 11 of the following year before the Stone of Destiny was returned to England. By then, the police had a good idea of the culprits, since they’d pulled library records at Scottish universities. (Hamilton had done a suspicious amount of research on Westminster Abbey.) However, the stone remained hidden, and no one was talking.

Eventually, feeling the pressure, the students made contact with two sympathetic town councilors. The stone had been repaired by a local Scottish stonemason and sat at the ruined Abroath Abbey. Once the police arrived, they removed the stone. The officers immediately placed it in custody, locking it in a cell.

Many public figures called for severe prosecution, but England’s governments wavered. If convicted, the four thieves would be martyrs. If acquitted, they would be heroes. To the consternation of more conservative voices, the theft was framed as a student prank. No charges were laid.

Eventually, the Stone of Scone was returned to Scotland in 1996—sort of. The English contended that it remained Royal property; it was merely being housed in one of the kingdoms ruled over by Her Majesty.

In 2014, a referendum was held asking the question, “Should Scotland be an independent country?” 2 million Scots said no. 1.6 million said yes.

Of the four students, only Hamilton survives. As of this writing, he is 96 years old. Hamilton became a noted criminal lawyer, and Stuart and Vernon, successful engineers and businessmen. Matheson was a teacher. All four mostly avoided the spotlight, but the Scottish nationalist movement considered them heroes.

There is one small, and likely apocryphal, footnote. The stonemason who repaired the Stone of Destiny was a known Scots nationalist named Robert Gray. He used three metal dowels to repair the stone, and there’s long been a rumor that a message was written on a slip of paper and inserted into one of these dowels.

True or no matters little: When King Charles III takes his seat, as so many have done before him, he will sit above a reminder that destiny is no certain thing.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

8 hp out of a 1 liter engine is dismal – but cool story

It is actually the notional tax rating. They were asthmatic, but not quite that bad. If you read the CAFE article the other day it shows how manufacturers adapt to circumvent the regulations rather than strictly comply, the English have just been doing it for a long time

The 8 HP rating was a tax category. The figure has nothing to do with the actual bhp produced by the side valve four cylinder engine. It was determined by a formula involving the stroke and cylinder diameter.

That engine probably produced around 20 bhp. The tax formula resulted in car manufacturers designing engines with long strokes and small diameter cylinders so they qualified for lower taxation levels than later over square engines would have done. This method of setting taxation levels was abandoned some time around 1960.

A pretty good movie was made of this story: the name escapes me.

It’s called Stone of Destiny – 2008 release.

The 8hp refers to the RAC horsepower, a taxation notation, not bhp. Just like, the Austin7, Morrris 8, Ford 10 etc.

And the reference to the wiper problem was a function of the pneumatic system driven off the intake manifold depression. Wiper speed was determined by what the throttle was doing!

Oh I see. Looks like more like 20ish hp? I could not find that early of an Anglia around here to quiz an owner about the quirks, but I read re: the wiper problem that you could lift throttle to get it working again. Anyway, not a relaxing car to drive down from Scotland in mid-winter!

Seems about right for bhp. I had a Series 2 Morris 8 (918cc side valve) back in the sixties and I seem to remember it was around 23 horsepower. I imagine the Ford 8 side valve made about the same, although the 1172cc version seemed to be capable of being tuned to some very respectable numbers, finding its way into many sporting vehicles in the 1950’s.

I tuned the 1172 engine in my later 100E Anglia using Aquaplane intake with dual SU carbs, an Aquaplane aluminium cylinder head and fabricated tri-Y exhaust system. It was never dynoed but used in club saloon racing was competitive with cars with around 50+ bhp. But it did tend to break con rods and a crank shaft or two.

My father had a cheaper version of the Anglia called the Popular. Commonly known as a “sit up and beg”. 3 speed gearbox was good for a top speed of about 55, cruising at 45.

Just after the first motorway (M1) opened in 1959 Dad thought it would be an intersting adventure to drive it to London. In those days there was no speed limit so the motorway was a magnet for drivers wanting to do the “ton” (100 mph). We chugged along at 45 – 50 in the slow lane with cars zooming by at top speed. My sister and I thought it was great fun but no doubt the grown ups were probably a bit spooked. Memories!

Ian Hamilton, the last surviving of the four, died at age 97 yesterday!

It seems amazing that the Ford would have been able to move at all towards Scotland with the big rock in the back plus some people in it. Must have had a good tailwind that day.

Funny, I first heard of this story from a magazine I was reading yesterday “How it Works”. Interesting story

I believe the “tax horsepower” was based on the bore x number of cylinders hence all the long stroke engines to reduce tax

You’re right

Taxable HP = Bore squared times number of cylinders divided by 2.5.

The Ford Anglia did not have “rear springs” to sag, just a single transverse spring. The same technology of the Model T or A etc.

The 100E engine was a major improved development the previous Anglia’s E93A 1172cc version. It was introduced in 1953 for the 3 box styled cars. The Harry potter Anglia arrived in 1959 with a 997cc overhead valve engine – a vast improvement.

The Anglia windshield wipers had a vacuum reservoir mounted on the bulkhead. Its function was to keep the wipers running for a while after wide open throttle eliminated a vacuum supply from the inlet manifold. When the reservoir was exhausted the wipers stopped.

The Ford Popular, generally known as the 103E was a budget version of the 1172cc Anglia and made from 1953 to 1959. To achieve the lowest price car reputation in the UK, Ford removed all non-essential features. So, there was no heater, air cleaner, oil filter, trunk/boot lock, turn signals passenger side windshield wiper or wiper vacuum reservoir. Without the reservoir the driver had the unenviable choice between getting up a hill/maximum power or seeing through the windshield.

My first car was a 1958 Popular, followed by at least two 1957s. A love-hate relationship.

BHP 23.4 @ 4000 RPM (R.A.C. rating 7.96 HP)