Media | Articles

When Alan Mann Racing Gave the Mustang Its First Victory

April 17 marked 60 years since the Ford Mustang’s public debut at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. The original pony car immediately became a pop-culture and automotive phenom, and it remains one of the most impactful cars in history. We’re celebrating with stories of the events surrounding the Mustang’s launch, the history of the early cars, and tales from owners. Click here to follow along with our multi-week 60 Years of Mustang coverage. -Ed.

On the Wednesday before the new Mustang debuted at this year’s Rolex 24 at Daytona, Ford presented its Spirt of Ford Award to the team behind the Mustang’s first-ever racing victory 60 years earlier.

That inaugural win wasn’t scored on American soil, nor even by an American team, but at the 1964 Tour de France and contested by British outfit Alan Mann Racing (AMR)—a team that had been established only that year by racer and subsequent team manager Alan Mann.

Mann passed away in 2012, but his sons, Henry and Tom, collected the award at the American Muscle Car Museum, and they continue to run AMR to this day. We spoke with them at Daytona a few days later about how an unknown British team from Byfleet, Surrey, got a big-time Ford contract, about what happened next, how their involvement with the original Mustang continues, and the mystery that still surrounds that winning car’s whereabouts.

Alan Mann was still a young man when the Ford connection began. “My dad worked for a Ford dealer on the south coast called Alan Andrews, which had a successful racing operation, and Ford of America invited a couple of British Cortina teams over to race in the Marlboro 12 Hours [at the now-defunct Marlboro Motor Raceway in Maryland] and at Bridgehampton in 1963,” says Henry. “My dad was running one of them with his British drivers, and Holman-Moody were running some Falcons with their NASCAR guys.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

When the Brits beat domestic Falcons it caused quite a stir, but rather than bristling at the unwelcome competition, John Holman saw an opportunity—his team disliked competing in European events with Galaxies and Falcons, so he introduced Mann to Ford management.

With Mann aged just 27, Ford suggested he establish his own company and run the European arm of its Total Performance program, which involved racing in various categories across continents. Things moved quickly.

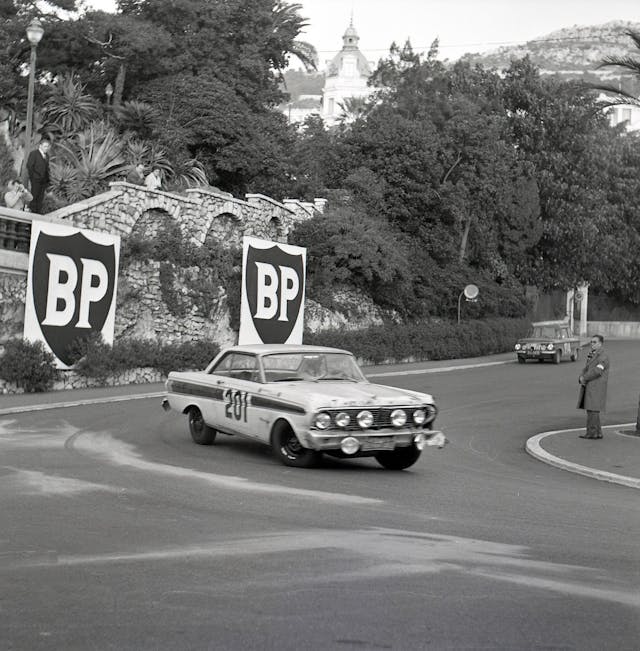

“That led to them running Falcons in the 1964 Monte Carlo Rally,” says Henry, noting that the Falcon shares much with its pony-car sibling. “The cars were all built at Holman-Moody, then brought into Lincoln Cars Ltd. in the Great West Road, which was Ford’s British distributor for American vehicles at the time.” Ford’s trust was repaid when the Falcon Sprint driven by Swede Bo Ljungfeldt came second to Paddy Hopkirk’s Mini Cooper S that January.

“After they got back from the Monte,” says Henry, “Ford shipped over an early pre-production Mustang, number 3 I think, with a 260 V-8 and a three-speed gearbox. It was fairly standard and not quite the spec it would end up being—there were still some Falcon bits on it—but they did testing and homologation work. It had to be very secret. When a photographer got some shots of them testing at Goodwood, he had to be persuaded to destroy his film.”

Come June, Ford shipped over four Mustangs with Hi-Po 289 engines for the Tour de France—a 10-day, 4000-mile marathon that lapped France like a boot pointing out to the Atlantic, taking in race tracks, hill climbs, and sprints as it moved clockwise from Rennes in the northwest and eventually back to Paris.

Three Mustangs would compete, the fourth acting as a support car driven by Alan Mann and cannibalized as necessary. All wore AMR’s new red-and-gold livery—much like a British postbox and now synonymous with the team—after Mann had struggled to distinguish his Lotus Cortina at the Nürburgring in 1964 from a number of others all wearing white-and-green war paint. “Ford would supply bodies in white or red, and red helped him tell them apart,” Henry says. “Then it was a case of ‘What goes with red?’ The first car in red and gold was a 1964 Lotus Cortina.”

A previous Hagerty story on AMR’s efforts covers Peter Procter and co-driver Andrew Cowan’s Tour de France win of the Touring class in-depth, but Henry notes that, along with exceptional driving, two other factors in particular contributed.

“They’d been a bit unsuccessful in the Marathon de la Route [a series of long-distance European road rallies] with two other cars, which was a pretty intensive event, and they went off the road in Yugoslavia but learned a lot,” he explains. “My dad was also lucky, because there was a Vickers [engineering] plant near AMR’s base in Brooklands, so there were a lot of really talented metalworkers and mechanics in that area, and a huge part of the job in those days was to keep the cars running.”

Not only did the Mustang win the Tour de France to end Jaguar’s long-term dominance, but another AMR Mustang placed second. Had the final Mustang not been disqualified for a push-start, it would’ve been a 1-2-3.

Alan Mann Racing went on to further success with the Mustang, winning the British Saloon Car Championship in 1965—50 years before the Mustang would officially arrive in dealerships in the UK—while Jacky Ickx contested some rounds of the 1965 European Touring Car Championship with one.

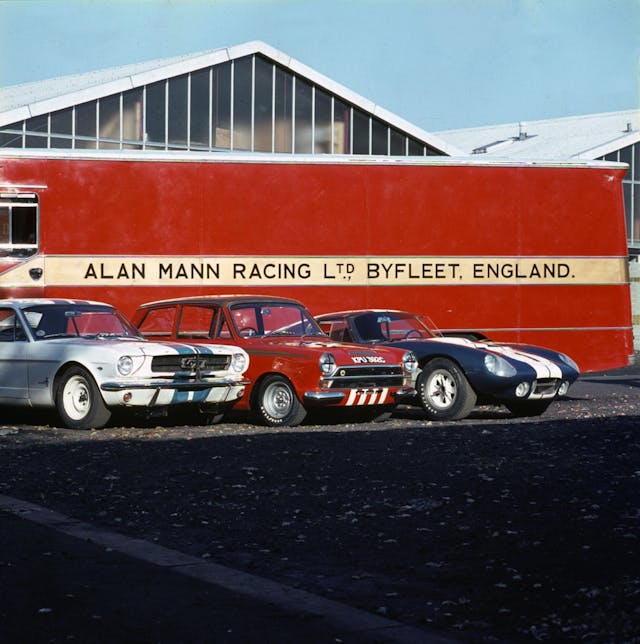

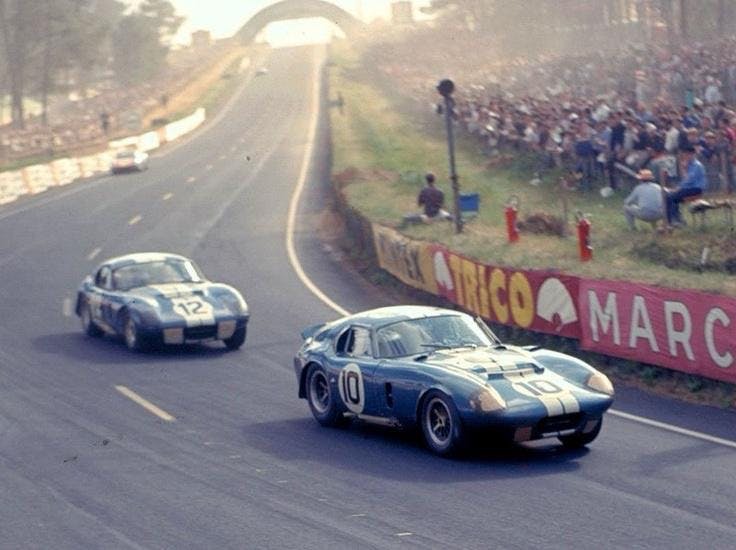

“After that there were no more Mustangs run by my dad in period,” Henry says. “It had kind of had its day in frontline competition, but AMR moved onto other things—the GT40s, Escorts, Shelby Cobra Daytonas…”

In fact, AMR won the 1965 World GT Championship with the Daytona, the 1965 European Touring Car Championship with the Cortina, and then took the Falcon and Escort to consecutive British Saloon Car Championships in ’67 and ’68. AMR even contested Le Mans with the GT40 in ’66 and ’69, though a finish eluded them.

Then Ford wound down its Total Performance program. “Once Ford pulled the plug in 1970 and went more into rallying, my dad withdrew from racing, didn’t see his old friends, and concentrated on his aviation business,” says Henry.

That was that—for a quarter of a century. Then a Cobra reunion at Sears Point in 1995 reignited interest, and when Goodwood’s historic events started to take off, Alan was invited to drive some of his old cars, apparently surprised that people remembered him.

Tom Mann adds that during their childhood, the two youngsters had no real appreciation of how successful their dad had been long before he started a family. They were startled when fans began approaching him for autographs at Goodwood.

The return of Alan Mann Racing proper came in a roundabout way in 2004. The brother of Henry’s school friend asked what he should campaign in historic motorsport, and Mann senior suggested a Mustang, citing strength, parts availability, power, and affordability. He soon found himself project-managing the build.

“He sourced a car in the U.S., contacted Lee Holman at Holman-Moody, and thought ‘Well, if he’s having one, I might as well have one too,’” recalls Henry. “He persuaded some of the mechanics from back in the day to prepare the car and started to get back into racing big time. It was like a switch flipped in his brain.

“Historic racing was quite clubby back then, and I think he just enjoyed spending time with [fellow racers] John Whitmore, Jack Sears, and Frank Gardner,” Henry remembers. “I was about 13 and started tagging along at races, going to get diff oil and coffee for mechanics, things like that. As he got ill, he said I should drive—he got me a driver coach and I started to get more involved.”

When the founder passed away in 2012, Alan Mann Racing was handed down to the brothers. Today it remains synonymous with Ford, being particularly renowned for its Mustang builds. It is still based on the same Fairoaks airfield site that has been AMR headquarters since 1970, and the brothers are currently finishing off a 1957 Fairlane and a Mk II Cobra, among various Mustangs. Occasionally they undertake road-car restorations, including the Mustang ePower that Hagerty recently tested, but mostly it’s about prepping ’60s Fords for historic motorsport, with Mustangs a particular speciality.

“My dad was a good development driver,” says Henry, “so we had a good spec sorted out on a historic Mustang by the time he passed away, and we’ve stuck with that ever since.”

At the Goodwood Members’ Meeting in England earlier this month, five of the 30-car grid contesting the Ken Miles Cup were AMR-prepared. Ford boss Jim Farley even shared an AMR Mustang with legendary touring car racer Steve Soper.

None of the four cars that entered the 1964 Tour de France were on the grid, but in this 60th year of the Mustang, Tom and Henry are keen to track down the long-lost winner. The fate of the three other cars, however, is known. The car disqualified from third position—registration DPK 5B—has already been restored by AMR and now appropriately lives in France. The second-place DPK 6B won the British Saloon Car Championship in 1965 and was then sold to a club racer, who suffered a fatal accident at Silverstone. The brothers believe it was subsequently crushed. And the support car driven by their father has been “in a leaky lock-up in north London since 1972, still with the Holman-Moody race engine in it, but it’s sadly not very good,” says Henry. “If the owner’s going to do anything with it, this is the year.”

The winning car—DPK 7B—remains the biggest mystery of all. “It was air-freighted back from France to America at the end of the rally and did a press tour, but no one knows where it is now,” says Henry.

“When we received the Spirit of Ford award, a guy introduced himself to us who’s writing a book about these cars, and he has a theory it started in the first Trans Am race, but it’s almost impossible to prove,” adds Tom.

There is, apparently, a concerted effort within Ford to find that car this year. Sixty years after a little British team gave the Mustang its first win a long way from home, nothing would make the brothers happier.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I love those Alan Mann coupes and the Terlingua Race Team Trans-Am coupe versions as well. Perhaps there is somehow a connection there.

Read a story in a different racing magazine years ago,that the FIRST Mustang to win ANY race, was a six-cylinder coupe out of New Mexico in mid-’64. Owner bought the car from small-town Ford dealer in New Mexico, and turned it into a Stock class racer. He won an event (forgot if it was NHRA or AHRA) in May or June ’64. Traded the car after a few months,for a Max Wedge Plymouth or Dodge a dealer had (from a bankrupt dealer’s inventory that the new dealer didn’t want).

I’ve always loved the fender mods done on these cars. Very tastefully done. The lights on the front are cool too.

I love that picture of the three Mustangs about to go down the straight away on the track. That looks like a fun track and a great view. Also love the blue Shelby’s on the truck.